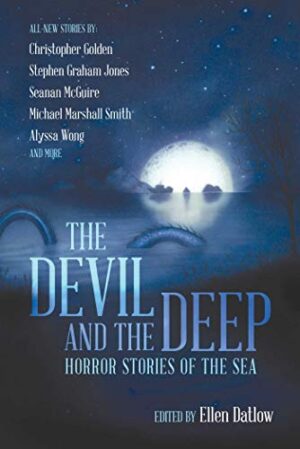

Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we cover Seanan McGuire’s “Sister, Dearest Sister, Let Me Show You To the Sea,” first published 2018 in Ellen Datlow’s The Devil and the Deep: Horror Stories of the Sea. Spoilers ahead!

Summary

“Inch by inch, I shuffled barefoot toward the parking lot, barely noticing and not caring at all when I stepped on the bits of glass and broken shell that littered the pathway.”

Tracy’s mother died when she was seven and her sister Maya was three. To make her mother’s memory linger, Tracy keeps her childhood bedroom as Mom decorated it: a “pink princess fantasy” of taffeta and silver sparkles. One night she goes to sleep cradled in goose down, to be awakened by salt water slapping her face. A dream? No. She really is lying incapable of movement in a rocky tide pool off Olympia Beach, with the icy water rising around her. There’s no use wishing on the brightest star above for her mother’s aid. She knows that when “mothers die, they die.”

She howls for help between waves. Maya answers from above. Does Tracy remember the panic attack Maya threw over a recent dental procedure? They gave her a drug-cocktail to send her “off to la-la land,” but Maya palmed the pills and earlier that evening mixed them into Tracy’s bedtime chocolate milk. Aren’t dental drugs amazingly incapacitating? Maybe Maya should become a dentist herself and just kill people on the side.

That’s how Maya dragged Tracy unprotesting into the car and to the beach. The why’s more complex. Tracy’s always resented Maya for being the product of a pregnancy that masked their mother’s cancer symptoms until treatment was ineffective. And the “Remembering Mom Society” she and her father formed has always excluded Maya, too young to remember details.

She hasn’t factored in Maya’s additional resentment for the overtures Tracy’s rejected, or recognized Maya’s sociopathic tendencies. “Never think I didn’t try to learn to love you,” Maya says from her safe vantage. But, she continues, Tracy is “unlovable.”

The tide swallows Tracy, and “the weight of the ocean” drags her down. Suddenly, something slices through the dark water, not a shark but a huge eel, “a silver razor of fins and scales and gaping jaws” that wraps around her. A voice whispers: Hello, little mermaid. You seem to have found yourself in a pickle. Would my little mermaid like to live?

Tracy has no breath to speak. She can only nod. They always want to live, the voice purrs, and three more eels begin to circle Tracy. You will owe me. You will be mine forever, but you will live. Do we have an accord? Imagining Maya a triumphant only child, Tracy nods harder. The first eel bites her throat. The others plunge through billowing blood into her mouth and down her throat, tearing at her tongue, finally settling in her chest. The witch-goddess voice says It is done. Before the first eel can join its fellows, Tracy blacks out.

Hours later she wakes in an emptying tide pool. She’s recovered enough to peel off Maya’s gauze bindings. Her mouth and tongue burn, so badly torn she can’t speak. The eels nestling in her chest have become her “kin and kind.” She makes it from the beach to the freeway. Someone reports a bedraggled, bleeding girl, and police and ambulances arrive. So does her father, and Maya, who hangs back. Maya doesn’t go to the hospital, where the doctors try to repair Tracy’s shredded tongue but fear she’ll never speak again. How their high-tech equipment misses the eels in her rib-cage, she can’t guess. It’s as the sea-witch ordains, leave it at that.

Tracy wonders if her living-drowned condition is the secret that Hans Christian Andersen wove into his fairy tale. Back home, her father reassures her that police will find her attacker. Tracy’s saddened that he’s about to lose both his daughters, but the tide must flow back to collect what it’s stranded.

Late that night, Maya slips into Tracy’s room. How, she asks. Tracy answers with the eels’ hissing voices: “I found another way.” Impossible, Maya pouts. Tracy can’t be here, can’t be real. In Maya’s petulance, Tracy hears the little girl who wanted no more than her mother’s embrace, but what must come….

Comes as the eels boil out of Tracy’s mouth and strike Maya before she can scream. They bite off her nose and lips and rip her throat open “like a flower.” The pink princess room turns red, as Tracy struggles for air. One eel slips back down her throat, restoring her breath.

Tracy drives to the beach and carries her still-twitching sister to the tide pool, another gift for the sea. The eels have left Maya’s eyes, so she can see the incoming waves. Tracy can’t respond to their pleading. A voice whispers Little mermaid, come home. It sounds like a mother’s voice, calling her not into pink fantasy but the black sea. Her lung-eels breathe in “salt and surrender” as she walks into the water. Behind her Maya struggles to scream and “everything was right, everything was true, everything was ever after, and [Tracy] was going home.”

What’s Cyclopean: The eels are silver razors; the Sea Witch’s voice is “the sound that seashells echoed in their oceanic screams”. And Tracy, after meeting her, speaks only in “the language of scar and scab.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Tracy falls quickly into the tropes of her genre around beauty and ugliness, scarred mouth turning her into a “horror”. Not just that it looks horrible—that she’s become something different and monstrous.

Libronomicon: Tracy speculates about Hans Christian Andersen’s inspirations, whether there was just a drowning girl and a bargain to be “spun into… sugar and morality and seafoam”.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Maya, it turns out, does not have a dental phobia. Ambitions of becoming a mass murderer, on the other hand…

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Seanan McGuire writes in rhymes, in verses and choruses. There will be fairy tales, Disney princesses wrestling with Andersen and Grim levels of bitter violence. There will be mermaids—maybe Deep Ones, maybe Discovery-Channel monsters with sharp teeth, but creatures of water and wishes. There will be curses and deals. There will be moments when all the genre savviness in the world won’t save you, only offer the knowing irony of tragic prophecy.

In this particular chorus, we’re playing with The Little Mermaid, both Disney and Andersen versions. It took me a moment, because the beginning seemed very Bonny Swans, but only a moment because I did recognize those eels. And the lost voice. And the broken glass. And then the direct citation, just in case you lost your way.

Here, genre savviness is important not because it helps you avoid unpleasant tropes, but because it tells you what rules you’re working with. Once you’ve met not-officially-Ursula, if you still handle your sister trying to drown you by writing out an accusation for the police… what would happen? Would it be like trying to float in a gravity field, or would you just get in trouble with the sea witch? Would you end up one story over in McGuire’s Indexing? As with ballads, get too close and the story has its own gravity field; better to cooperate with the reigning physics. Even if stories, like elder gods, follow their own goals that may have little overlap with human happiness and survival.

Another question: how long has Tracy been in a fairy tale? Did it start when her mother put stars on her ceiling, or when she died—or when the stars stayed up to take on a half-life of their own? Maybe it started when her sister fell into the resentful patterns of a trope-ish stepsister. Or maybe there was nothing offering deals under the sea until all those things came together to invoke them. Every fairy tale has a long prologue of day-to-day pain that could split off in any number of directions, right up until the first “once”.

Has Maya been in a fairy tale for longer? Sibling rivalry sometimes results in homicide, but not so usually in mulling over the delights of future and less personal murders. Something—someone?—persuaded her that it was better to be the villain. Given the subtle shout-out from her career plans to the Little Mermaid musical team’s previous major work, I’m going with a man-eating alien plant. They do say the meek shall inherit, and who’s more meek than a cute toddler? Ursula the Sea-Witch versus Audrey II, coming soon to a theater near you.

Of course, Audrey II is a mean green mother only to her own spore-children—whereas the Sea Witch seems willing to adopt her new-made mermaids. Whether she’s a good mother is another question. Tracy recognizes an “ever after”—no adverb included. Maybe there’s wonder and glory and lots of friendly eels, but maybe there’s the drudgework of a Cinderella or the protective prison of Rapunzel’s tower. I wouldn’t care to bet.

I do wonder if there’s an actual verse and chorus behind the story here: both this title and “Down, Deep Down, Below the Waves” have scansion that might ultimately mesh into a larger ballad. And McGuire does moonlight as a filksinger with an extensive catalog. Then again, if you both write lyrics and write as many short stories as McGuire does, there will be enough lyrical titles to make a ballad whether you will or no. “With Graveyard Weeds and Wolfbane Seeds” and “In Silent Streams, Where Once the Summer Shone”, probably part of the cryptid McGuire ballad. “The Great Tarantula Migration of 1972”, probably not—though you never know.

Anne’s Commentary

Here I was, assuming from the title that this story would be about the tender reunion between two Deep One sisters, the elder metamorphosed, the younger beginning her change. Instead McGuire’s given us siblings that more or less hate each other’s guts. Tracy is the lesser hater; she merely looks forward to the day when she and Maya leave home and have to endure each other only at holidays. Maya hates more intensely. She plans to kill Tracy without getting caught, and while allowing herself time to monologue at her victim until drowning doesn’t seem so bad—at least the water will muffle Maya’s petulant-toddler whine.

But there are more deities than Dagon and Hydra and Cthulhu under the sea. There’s also a sorceress so powerful she might as well be divine. Hans Christian Andersen calls her simply “the sea-witch,” while Disney dubs her Ursula, a fine villainous name. Andersen’s sea-witch has a pet toad and fat water snakes. Ursula has moray eel minions, which are what McGuire opts for. Few sea creatures look more sinister than morays, plus you can imagine them being sinuous and slimy enough to squirm down a person’s throat. How they might serve as amphibious lungs would be a good dissertation topic for a marine cryptozoologist.

All three “little mermaid” stories agree that the sea-witch’s fee is the boon-seeker’s voice. Andersen’s witch wants the little mermaid’s voice because it’s the sweetest in the undersea world and the best thing she possesses. She also believes the mermaid means to charm her terrestrial prince with her singing, which could read as her wanting the voice-deprived mermaid to fail. But she wouldn’t gain anything by that failure—Andersen’s merpeople don’t have souls, at least not the immortal ones humans possess. Ursula, on the other hand, does want Ariel to fail with her prince, because then she could plant Ariel in her polypous garden of “poor unfortunate souls.” She takes Ariel’s voice knowing that Eric can only recognize his rescuer-from-shipwreck via hearing, having never seen her clearly. Andersen’s witch has a polyp-garden as well, but its monstrous growths are “natural” in her domain, not twisted souls.

I wouldn’t be surprised if McGuire’s sea-witch has a polyp-garden, one of rich biological diversity more likely than one of trapped spirits. She doesn’t claim it’s Tracy’s soul she’s after—unless that’s implied in Tracy becoming hers forever. It is uncomfortably Ursula-like for her to expect Tracy to surrender autonomy, maybe what her lost voice represents. With her vocal organs shredded, Tracy can speak only through her resident eels, which evidently speak for the sea-witch.

Ursula is clearly Disney’s villain, though her torch-singer stylings and quippy malevolence give her a certain roguish appeal until she goes all Elemental Mayhem at the climax. Andersen’s witch also has bizarro charm, as when she ties her water snakes into a ball to scrub her cauldron clean. She drives a hard bargain with her mermaid, but she warns her in advance of the prices she’ll pay in exchange for human form. I’d call her amoral rather than evil. I’m unsure how much Andersen’s contemporary audience would have differed, but there’s been much debate about how he ended his story with the mermaid’s resurrection into a “daughter of the air,” an earthbound ethereal capable of entering heaven as an immortal soul after three hundred years of good deeds. That denouement has always felt off to me, especially when in the last paragraph he adds that exposure to good children will knock a year off the air-daughter’s “sentence.” Whereas each tear the “daughter” sheds over bad children will add a day.

Kids, you better behave! Otherwise it’s on you that the mermaid has to waft around for who knows how much longer before escaping her ethereal gig.

Andersen’s mermaid and Ariel share the admirable motive of wanting to go two-legged in order to explore the terrestrial world, but that motive takes second place once that cute two-legged prince falls off his ship. Love at first resuscitation! Not my favorite trope. Whereas Tracy’s motive for accepting the sea-witch’s deal is to STAY ALIVE. You don’t get a more understandable goal than that. As the sea-witch purrs, “They always want to live.”

Still, the first thing that goes through Tracy’s oxygen-starved mind, on hearing the sea-witch’s conditions, is how Maya will win if she’s out of the picture, inheriting the perfect life she’s always envied. These sisters have some complicated shit going on. Understandably, given their mother’s death when they were so young. Given Mom’s possible favoring of Tracy—that princess bedroom! Given Dad’s much stronger attachment to Tracy after their loss. Given Maya’s emotional instability (personality disorder?). Given how Tracy nurses her resentment of Maya for causing Mom’s death by rejecting Maya’s overtures of sisterly affection.

Is Maya right that Tracy is unlovable? Tracy denies it. Is her popularity superficial, with a darkness beneath the shiny surface that makes her reply to questions about the princess-pinkness of her room with: “My mother chose the color. My dead mother.” And she thinks this answer is “quick and clean and easy.”

At any rate, Tracy has met her match in the sea-witch, a being “deeper and older and wilder” than herself. The voice whispering for its little mermaid crosses a “rippling black sheet of the sea” that’s “a far cry from [her] pink princess fantasy.” Nevertheless, it sounds like home, like the voice of a dark mother who’s not confined to the “hazel tree” of death but who ripples free and broad forever.

Maybe from pink to black isn’t such a bad bargain after all?

Next week, we go deeper into Louis’s “nightmare” in chapters 16-18 of Pet Sematary.