I love to read about complicity. I would crawl across broken glass or do my most hated chore (vacuuming) if at the end of it I got to read about humans grappling with our culpability in unjust systems. The first science fiction book I remember reading and understanding as science fiction was Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game, closely followed by Speaker for the Dead and Ender’s Shadow, and that series set a lifelong template for my SF consumption. They are stories about complicity chiefly. When Ender complies with the understood rules of his world, incalculable harm results. When he rebels, the same. On a meta level, I fell for these books first, then later learned that Orson Scott Card hotly opposed gay rights—a shattering realization for me at fifteen. It left me with a nasty feeling that I had, by loving these books, inadvertently forwarded an agenda I passionately disagreed with.

To this day, my favorite SF books and shows are those that grapple with the complicities we can and can’t escape; the books that don’t try to salve our conscience by insisting a wrong done is not wrong if it’s intended for the greater good. These books include the work of Micaiah Johnson, the politics episodes of Deep Space Nine, Erin Bow’s Prisoners of Peace duology, N.K. Jemisin, any backstory on my girlfriend Officer Aeryn Sun, The Ministry of Time, Stephanie Saulter—and, of course, Yoon Ha Lee, whose debut series Machineries of Empire rewired my brain.

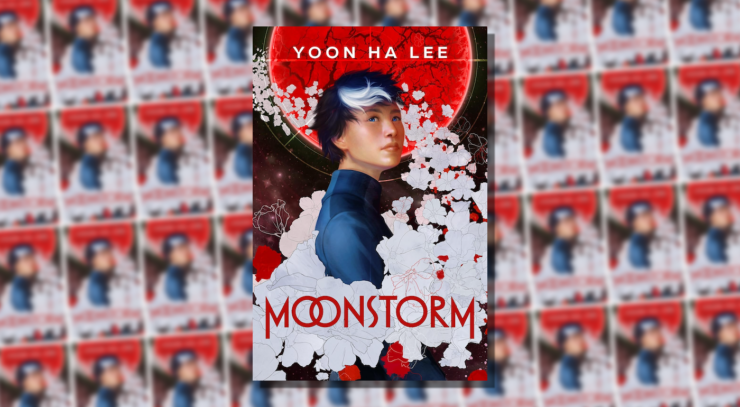

In Lee’s Moonstorm, the first in a planned YA trilogy, we meet a young Hwajin at the precise moment her world falls apart. The child of a clanner settlement, living outside the strictures of the Empire of New Joseon, she is saved from a sudden, thorough, horrifying attack on her community by a soldier of the Empire. “The Empress keeps all her children safe,” promises the pilot who rescues Hwajin, and she is swept away to be a ward of the state. Six years later, now going by the name Hwa Young, she attends a military readiness boarding school and dreams of piloting a neurolinked mecha herself. She believes in the Empire with a child’s desperate loyalty, and she is determined never again to be that fearful child of long ago, hiding in the reeds and waiting for rescue. When she and her friends are recruited as lancer pilots to fill urgent personnel gaps, she believes that her dreams are finally coming true—but as she wades into battle, she starts to learn that her adopted world is more complicated than she supposed.

So far, so familiar. YA protagonists are always heading off into battle at sixteen—because that’s the preferred age of the genre’s demographics—and I am now officially “where are all the damn grown-ups” years old—so I admit to some skepticism heading in. Lee’s got a few things going for him, though. First of all, it’s clear that the recruitment age has been lowered only because things are going extremely poorly in this sector. The clanners are making inroads against the Empire, a bunch of their lancer pilots have died, and desperate measures are now called for. None of the adults like the situation, but they’re making do with the orders and resources they’ve been given. We also get some ominous hints that these children and young adults are being deliberately separated from older adults, though the import of that separation hasn’t fully been revealed yet.

Buy the Book

Moonstorm

It’s also a shrewd way to keep the reader invested in Hwa Young. At sixteen, she’s still young enough to feel like a sympathetic protagonist even as she’s allowing herself to be used to further the destructive agenda of a powerful empire. It made an interesting contrast to Emily Tesh’s brilliant—though difficult—adult novel Some Desperate Glory, which flatly refuses to let its stormtrooper protagonist be sympathetic or even, frankly, bearable. Here, the cracks in Hwa Young’s comfortable, conformist worldview are present from the beginning. Lee smartly includes an early set piece that establishes her ability to jump in and take charge when necessary. The scene highlights her competence, care for her classmates, and, perhaps most importantly, the legacy of the sudden disaster in her childhood. Recognizing that she is the only one among her classmates who understands how much can be lost in a single hour of violence, she rushes to take charge rather than waiting to be saved. The scene acts as a strong reminder, just before Hwa Young launches into her career as a Stormtrooper-in-training, that she’s a traumatized kid who wants to protect others, and whose circumstances have pushed her to believe that the only way to do that is to align herself with the Empire.

Of course, her complicity has an expiration date. Hwa Young is chosen by one of the neuralinked mecha suits, the most dangerous of the lancers, the one that has claimed the lives of five would-be pilots, Winter’s Axiom. Alone among the lancers of the fleet, Winter’s Axiom possesses a singularity lance, the fleet’s most powerful weapon, which can singlehandedly destroy an entire starship. In their very first training exercise as a team, Hwa Young and her classmates are asked to play as clanners defending Carnelian, Hwa Young’s original home, the one she thought had been wiped out entirely when she was ten. Turns out, the clanners have since rallied, and Carnelian has become the forward base for their operations—which makes it a prime target for the Empire’s forces in this sector. In other words, for Hwa Young and Winter’s Axiom.

One of my most tellingly Catholic character traits is that I find guilt-based suspense the most suspenseful. First-most suspenseful is when someone has done a wickedness, and we are waiting to discover if they will be found out (your Macbeths, your The Secret Historys). But a close runner-up is the genre of suspense Moonstorm dabbles in, where you know that Hwa Young won’t be able to maintain her allegiance to the Empire, and that disillusionment is coming for her faster than slow. The harder she commits to her future as a lancer pilot, the more acutely I felt that suspense. Will an exercise where the Empire has to defeat her own homeworld break the spell? What about an actual battle against clanner forces defending her homeworld? If these betrayals of the person she used to be won’t break her away from the Empire—and this is the pith of the suspense, the source of the dread—then how terrible must it get before she’s willing to reevaluate? How far will any of us go along with the oppressor to avoid becoming the oppressed?

Moonstorm starts with a bang and never takes its foot off the gas, tearing through schemes, trauma, chaos, and battles, with just enough pauses to give breathing room to its characters and relationships. By the end, the board has been reset, and the characters are poised to make their next moves. I can’t wait to find out what they’ll be.

Moonstorm is published by Delacorte Press.