Dinosaurs are nature’s celebrities. We love them. Many of us, in the near-ubiquitous “dinosaur phase” of our youth, quickly master names like Tyrannosaurus, Diplodocus, and—the challenge of any young fossil fan—Pachycephalosaurus by the time we start kindergarten. But dinosaurs are changing so fast that the monstrous creatures we imagine in our youth become strangers as scientific discovery continues to tweak what we know about them. This disjunction spurs myths and misunderstandings that persist for decades, and often obscure how wonderful dinosaurs truly were. Time to do a little pop culture housekeeping to clear out old assumptions.

1: Tyrannosaurus and Apatosaurus lived together

As a kid, I spent hours staging battles between my plastic Tyrannosaurus—king of the tyrant dinosaurs—and a stocky, long-necked Apatosaurus model. But the dinosaurs never would have met each other. Apatosaurus roamed western North America about 150 million years ago, over 80 million years before Tyrannosaurus evolved. In fact, a greater span of time separated Apatosaurus and Tyrannosaurus than separates us from that most famous of the carnivorous dinosaurs—a relatively scant 66 million years. But sandbox dinosaur fans, take heart. Even though Tyrannosaurus never ate Apatosaurus, the giant predator lived in the same Late Cretaceous habitats as Alamosaurus—a huge sauropod dinosaur found in the southwestern United States. Tyrannosaurus probably enjoyed sauropod steak, after all.

2: “Dinosaur” means anything ancient and reptilian

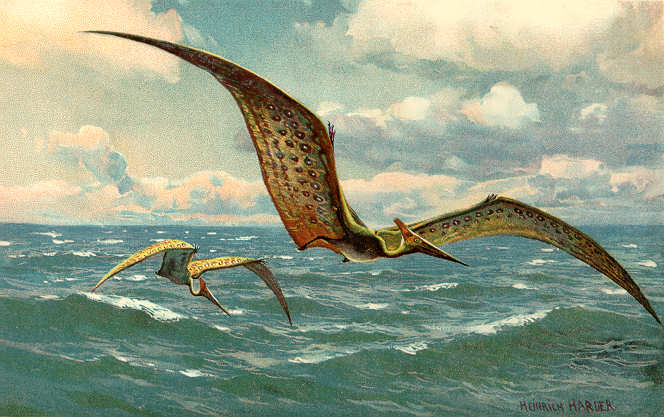

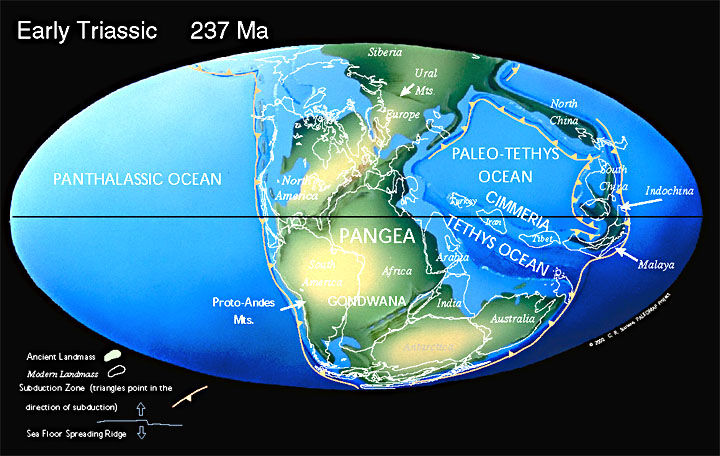

Even though the word is familiar, “dinosaur” is a technical term that applies to a specific group of animals that are united by a suite a shared characteristics and bound together by evolutionary history. Just because some prehistoric creature was big or had nasty teeth doesn’t automatically make it a dinosaur. The proof is in anatomical detail and the creature’s specific relationships. In the bigger evolutionary picture, dinosaurs were just one lineage within a group called archosaurs. This group also includes pterosaurs, crocodiles, and their closest living relatives, all of which split from each other by about 245 million years ago. Dinosaurs were a specific part of this archosaur radiation, distinct from other archosaurs and other forms of prehistoric reptiles. While they lived alongside dinosaurs, the flying pterosaurs and marine reptiles such as the long-necked plesiosaurs, fish-like ichthyosaurs, and swimming lizards called mosasaurs were not dinosaurs.

3: Big dinosaurs had butt brains

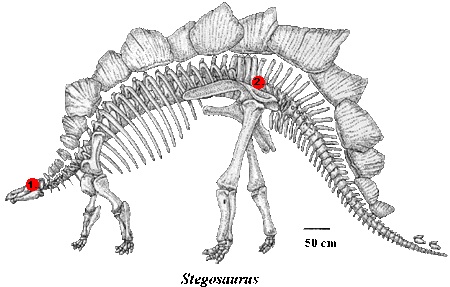

Some dinosaurs—such as the mighty sauropods and the armored Stegosaurus—had extra-large cavities in their hips. The wide spaces were associated with the neural canal, where the spinal cord passes, and so 19th century paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh speculated that the space housed a “posterior braincase” that helped the dinosaurs coordinate their legs and tails.

But paleontologists now know that no dinosaur had a second brain. First, many different kinds of vertebrates have a slight expansion of the spinal cord in the vicinity of their limbs. This slight swelling of the nervous system helps regulate limb movement. But Stegosaurus and sauropods had even larger expansions that probably housed a strange feature called a glycogen body. This kind of tissue, seen in the hips of birds, might store energy-rich carbohydrates, although zoologists still aren’t entirely sure if this is the case. One thing is for sure, though—dinosaurs did not have brainy butts.

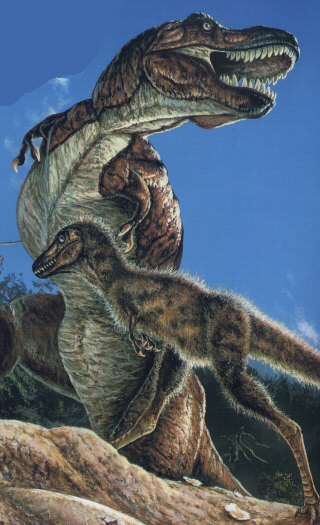

4: Tyrannosaurus arms were wimpy

Tyrannosaurus forelimbs look small compared to their bulky bodies and massive skulls, but the appendages were not as weak as they might appear. The arms of Tyrannosaurus were stout and heavily-muscled, so much so that the dinosaur could probably flex an excess of 430 pounds with each arm. No human bodybuilder can match that. And, if we’re going to tease any dinosaur for small arms, Carnotaurus is a more apt target. In the arms of this carnivore, the bones of the lower arm, wrist, and hand are compressed into a short skeletal stack attached to a flexible upper arm bone. If Carnotaurus wanted to attack another dinosaur with its arms, the predator’s forelimbs would have only been able to do ineffectual pinwheels.

5: Dinosaurs dragged their tails

You’d think that Jurassic Park and decades of fantastic paleoart would have killed this one, but apparently not. While generations of paleontologists reconstructed dinosaurs with limp, drooping tails, since the 1970s researchers have been more properly restored dinosaurs with spines held parallel to the ground and lifted tails. This evidence not only comes from osteology—including tail support structures such as strengthening ossified tendons in some dinosaurs—but also from trackways that fail to preserve the tail drags that would have been expected if the dinosaurs were walking in a Godzilla pose or had slack tails.

6: Dinosaurs were the terrors of small mammals

6: Dinosaurs were the terrors of small mammals

Our mammalian ancestors and cousins remained relatively small during the Mesozoic reign of the dinosaurs. This has often been taken as an indication that the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous landscapes were dangerous places for the small and fuzzy. But mammals ate dinosaurs, too. A specimen of Repenomamus—a 125 million year old mammal about the size of a badger—had baby dinosaurs preserved in its gut contents. No one knows whether the mammal scavenged the infants or actively raided a nest, but the sharp-toothed mammal was certainly capable of eating little dinosaurs. Other mammals chewed dinosaurs post mortem—some dinosaur bones show distinctive gnaw marks that could only have been created by small mammals.

7: Dinosaurs always lived in a humid, endless summer

The classic imagery of prehistoric dinosaurs features fantastic animals in dense jungles and murky swamps. Some dinosaurs inhabited environments like this, that’s true, but the whole diversity of dinosaurs actually occupied a diversity of habitats all over the globe for about 160 million years. There were even dinosaurs in the snow. Late Cretaceous sites in the High Arctic contain the remains of dinosaurs that lived in relatively cool habitats that would have been dark for much of the year, and, based on ancient climate reconstructions, which probably experienced snowfall. A fuzzy tyrannosaur striding through the snow is quite different than the sauropods lumbering through weed-choked wetlands that I grew up with.

8: Quirks of the ancient Earth made dinosaurs so big

Why were the biggest dinosaurs so much larger than any terrestrial creature alive today? There’s been no shortage of explanations, including the idea that gravity was different or there was more oxygen in the air. But gravity in the Mesozoic was the same as it is today, and, in fact, reconstructions of the ancient atmosphere indicates that the atmosphere’s oxygen content might have actually been slightly lower during the time of dinosaur giants. Instead, dinosaurs such as Supersaurus got so large because of two factors of their biology. Not only did sauropod and theropod dinosaurs have special air sacs that made their skeletons lighter without sacrificing strength, the fact that dinosaurs reproduce by laying clutches of small eggs allowed them to get around the reproductive constraints that prevent land-dwelling mammals from becoming larger.

9: All dinosaurs were big

The biggest dinosaurs are the ones that immediately fire our imagination. But not all dinosaurs were giants. Part of what made dinosaurs so successful is that they occupied a range of body sizes, from small to absolutely gigantic. Among the smallest dinosaurs were pigeon-sized forms such as the feathery, bird-like Anchiornis and the fluffy little theropod Scansoriopteryx. And, of course, babies of these diminutive dinosaurs would have been even smaller still.

10: Dinosaurs are dead

Dinosaurs are still with us. Even though the charismatic, non-avian forms all died out in a devastating mass extinction 66 million years ago, the avian lineage survived and persists to this day. Indeed, the dinosaur lineage known as “birds” evolved by 150 million years ago, and these feathery dinosaurs—from hummingbirds to ostriches to penguins—remind us of their lost relatives today.

Brian Switek is the author of My Beloved Brontosaurus and Written in Stone. He also writes the National Geographic blog Laelaps

Okay, picture 9…

Disturbing since most of us know what happens 5 seconds later.

Wait, doesn’t 10 contradicts 2? Do birds actually evolved from flying archosaurs instead of dinosaurs?

Thanks for the comment, Skadi.

Birds are not a totally separate group. They are one lineage of dinosaur, and the entirety of the Dinosauria is a group within an even bigger group called the Archosauria.

This image might help: it’s a diagram of the Archosauria, showing the various lineage within the group (including dinosaurs)

Now have a look at this diagram: it represents the more specific group of dinosaurs to which birds belong

Basically, birds are a lineage of dinosaur, and the Dinosauria is a big lineage within the even bigger group the Archosauria. These are sort of road markers for different levels of specificity.

– Brian

What a coincidence, we just watched Jurassic Park this past weekend :) I credit that movie with my ‘turned into birds’ knowledge :)

I think I was 10 when that movie came out, and I still have so many images and associations with it. My son scratched me in the stomach a few nights ago (he’s a baby and we hadn’t clipped his nails) and my first thought was “VELOCIRAPTORS!”. And we still compare my toddler to a raptor – he’s just now figuring out how to open doors, uh oh!

Is there any truth at all to the notion in the movie that raptors were really smart, or was that just movie magic?

Lisamarie –

I just watched Jurassic Park yesterday! I was on a flight home from a conference, and thought quite a bit about flying dinosaurs – that is, birds – while up in the air.

So, the smart raptors. Back in the 80s, there were a few paleontologists who tried to plot out dinosaur brain size relative to body size. A relatively small, sickle-clawed form similar to Velociraptor – named Troodon – had a relatively large brain for its body, similar to a bird rather than a lizard or crocodile. This hinted that these dinosaurs were smart. Plus, based upon quarries where multiple Deinonychus skeletons were found, paleontologists hypothesized that “raptors” might have been pack hunters that worked together. You need to be a bit smarter to strategize a hunt.

All of this work has been questioned. Troodon and similar dinosaurs had relatively big brains, but we can’t tell how smart they really were. (But it’s interesting to note that smart birds such as ravens are living dinosaurs.) And just because multiple dinosaurs are buried together doesn’t necessarily mean they died together. Trackway evidence shows that “raptors” sometimes walked in pairs or small groups, but we don’t know how socially complex their behavior was.

Basically, Jurassic Park took some leaps in depicting how smart Velociraptor was. And if the part used round doorknobs, then they wouldn’t have had to worry about dinosaurs opening doors! – Brian

WHY ARE YOU DESTROYING MY CHILDHOOD? Just kidding, great post! It’s always interesting to see how we’re able to develop our understanding of the animals that lived millions of years ago. Six-year-old me could get pretty snarky about correcting information that appeared in my books about dinosaurs, and I’m glad to see corrections are still happening 25 years later.

Wait.

You mean Transformers got it wrong? The Dinobots should have been… the Archobots?

Swoop should never have been part of the team?

Grimlock and Sludge were separated not only by region but by 10s of millions of years difference in fossil age?

What aren’t you telling us about Slag or Snarl?

I’m at a loss for words right now…

What exactly are the reproductive constraints that prevent land-dwelling mammals from becoming larger?

Could you elaborate more on number 8? There’s a lot of evidence compiled from several different fields which point to oxygen levels being higher in prehistory than currently is standard. A commonly cited researcher on this topic is Robert Dudley, but I’ve heard similar claims in astrophysics classes discussing the evolution of our planet.

Finally, I’m particularly doubtful as your explanation leaves many other unanswered questions. Why were plants and insects also so much larger during this time? Insects in particular pose problems as without a more advanced circulatory system, it wouldn’t make sense for them to be able to survive without a greater supply of energy.

My concerns may be misworded, and you do sound far more knowledgable on the subject than I, but everything else on this list I knew and makes total sense, where as this flies directly in the face of so much I have learned in biology and physics classes.

Thanks for your time!

OK, maybe dinosaurs aren’t dead, but they have definitely jumped the shark, or ichthyosaur or whatever served the purpose at the time.

LDT and LG:

Thanks for chiming in. The question of why dinosaurs got so big has a pretty complex answer, and admittedly I tried to condense a response into a small space for this list.

Land-dwelling mammals don’t grow as large as the biggest dinosaurs because of reproductive reasons. Carrying a single embryo internally for a loooooong time is a huge energy draw, not to mention post-natal care. Dinosaurs avoided this by laying eggs and providing comparatively minimal parental care. I’ve written about his before, here, if you want more details.

And LG, I suspect you’re thinking of the Carboniferous period – millions of years before the first dinosaurs evolved. Atmospheric oxygen levels have fluctuated throughout Earth history, and were indeed high during the Carboniferous. This was the time of big dragonflies and millipedes, but when the ancestors of dinosaurs (and mammals) were still small, lizard-like animals. Oxygen levels fell afterwards, and have continued to fluctuate. During the time of the giant dinosaurs, though, oxygen levels were comparable to today or slightly lower.

Believe it or not, I actually wrote about this topic in response to tweets by Jose Canseco. Check out the two-part response here and here. – Brian

I’d add the myth that sauropods held their necks erect. Unfortunately, there are still paleontologists who hold to this.

The structure of the tendons along the back of the neck and the sheer unmanageable blood pressure required (a large sauropod would need a heart that filled most of its body cavity) make it utterly unreasonable unless the animal was aquatic. Brachiosaurus probably did hold its neck erect but only when underwater.

Terrestrial sauropods probably used their necks like big sweeping poles to get at shrubs and foliage over a wide area, rather than browsing up trees.

The argument actually gets quite ridiculous with people suggesting things like multiple hearts running up the neck. Evolution of valves against high blood pressure like that is (to be kind) ‘problematic’ and there is no evidence that any vertebrate has ever had more than one heart. It’s like people are so wedding to the paintings of sauropods waving their heads around in the air that they can’t quite accept that it probably wasn’t that way…

@@@@@ Laelaps re: mammals and carrying young. In which case wouldn’t marsupials, extinct marsupial allies and montremes have reached much larger sizes? I’ve always suspected the answer as to why dinosaurs grew to be much larger than mammals lies closer to more efficient flow-through lung function (assuming dinosaurs have lungs more like birds) and a bone structure that was more similar to birds than mammals. Bird bones are light but strong. Good for flight, but also good for supporting a lot of weight in a non-flying dinosaur. Mammal size is probably limited by their bone structure, which is strong but dense and therefore very heavy. Mammal bones are great if you are small and scurrying and need to be sturdy if attacked by a predator, but not so good for large morphology.

However, having said that, terrestrial birds like rattites don’t reach dinosaur sizes either, even in the absence of mammal competition such as in New Zealand, so maybe there is more going on. Possibly, dinosaurs have a metabolism that ran differently and more effeciently? Possibly the fundamental ecology was different and the flow of energy through the dinosaur-era food webs were different, but not for reasons like oxygen levels? It’s an interesting question and still doesn’t have any clear answers as yet.

Just a quick reply. Hope I don’t sound too attacky or anything.

Nice article by the way.

Chris

And the myths may keep on coming, as witness the controversial reconstruction in the American Museum of Natural History (NYC) of a rearing momma Barosaurus protecting her young from an Allosaurus. Mighty impressive display, even if unsound.

Of course, the most pernicious myth is that we are not allowed to even speak the name “Brontosaurus” for fear of being shamed as “dino-dummies”.

CPJ: At least some sauropods held their necks erect, and such neck postures didn’t require an aquatic habitat. I discuss some of the ideas in this post.

Eugene: The rearing Barosaurus might be controversial, but it’s not a “myth.” Indeed, biomechanically, the sauropod could have reared back in such a fasion. The question is whether the dinosaur could have kept pumping blood up to its head while standing. I think the AMNH Barosaurus mount is reasonable and thought-provoking speculation.

I don’t care what anyone says, the dinos we learned about when I was in grade school were awesome! And given a choice between factual and awesome, I will choose awesome every time!

re: #10. There are at least 2 theories besides the meteor strike.

1. They all disappeared in the VelociRapture.

2. They DID make it onto Noah’s ark but were swept overboard by a massive wave while rearranging the deck chairs.

As far as I’ve learned (which don’t get me wrong, isn’t too far), there are many reasons theorized as to why dinosaurs and other animals had reached such gargantuan sizes in the past. Multitudinous reasons for the sizes attained by dinosaurs in particular likely existed. The foods they consumed, they ways they digested including a longer digestive system, the oxygen, their reproduction, being ectothermic, and generally speaking some evolutionary benefits of being so large. Etc, etc.

Another concept that’s hard to wrap your head around is the now more common ideal that dinosaurs weren’t all scales. Having feathers for many just doesn’t seem as tough, haha.

On to more pressing matters…

Cera, Little Foot, Petrie, and Spike couldn’t have been friends =”[. Nor could have a Tyrannosaurus have killed Little Foot’s mother. My childhood was a sham. A dirty, dirty sham.

Great post, however.

**Nor Could have Little Foot’s mother have been killed by a Tyrannosaurus. My childhood was a sham. A dirty, dirty sham.

Great post, however.

beautiful, completely beautiful! and it´s very very timely, considering the soon-to-be released 3D version of Jurassic Park. and like Lisamarie, this movie introduced me to the “birds evolved from dinosaurs” theory which absolutely blew my mind when i was 13!!!! and now that we´re talking about dinosaurs, there´s this book: All Yesterdays (http://www.amazon.com/All-Yesterdays-Speculative-Prehistoric-ebook/product-reviews/B00A2VS55O?pageNumber=2); it´s a good read (albeit a slightly short one); the illustrations are awesome, even in the digital version

Re #10…if ypu’ve ever raised chickens or tangled woth a goose ypu -know- :-)

@@@@@ Laelaps

This will be a long reply…

Certainly small sauropods, not much larger than a giraffe, could have held their necks aloft out of the water, but nothing larger than that.

The question is not whether some sauropods held their head aloft, but whether they did so out of water, which your article never actually addresses. You make no reference to that argument at all and just jump to a terrestrial life-habit.

The most parsimonious explanation is that sauropods where the bone structure indicates an aloft neck posture must have been aquatic. If they left water bodies their heads would have been allowed to droop to prevent brain death from lack of blood. For an example of an aquatic animal with ‘anchor’ feet instead of paddles, we have the hippo, if that is a concern (one rather bizzare argument raised sometimes is that sauropods couldn’t have been aquatic because they don’t have flippers. Hippos. Cough, cough. Look at a hippo).

I’ve read your article and, I’m sorry, but it would not stand up to peer review… there is at least one large leap of logic and a few dishonest arguments. If I read it correctly, the argument you present is that (some) sauropods must have extended their necks based on their bone structure. This leaves two possibilities.

1) They were aquatic

2) They had a whole set of implausible physiological adaptations (hereafter ‘magic physiology’) that don’t match any known vertebrate physiology

I’ll work through your article (somewhat) as if I were peer reviewing it for a scientific journal. I will be a little harsh below, but an actual peer review would be much much harsher…

Taylor and collaborators are disingenuous when they state that sauropods must have held their necks high “Unless sauropods behave differently from all other extant amniotes”.

The argument is disingenuous because they then contradict their own statement by then arguing the complete reverse: that sauropods were able to hold their heads aloft by behaving differently to all other forms of extant amniotes.

When you break down the argument it looks like this.

Your statement that a ‘considerably more powerful heart and blood pressure’ is required is a profound understatement. The heart would need to fill the entire chest cavity and the blood pressure would be high enough to potentially rupture bone.

You do go on to explain that a very large heart is needed, but you seem to shy away from conveying the sheer silliness of such a large heart. This gets dangerously close to cherry picking data and ignoring an article because it doesn’t line up with your theory. The next paragraph is where your argument about weird physiology kicks into gear.

Having already argued that sauropods must have kept their necks upright because of what we know about living vertebrates, you then go on to argue that sauropods must have kept their necks erect in a way that defies everything known about living vertebrates (this is the disengenious logic noted above).

You have (thankfully) rejected the 1978 article by Bakker, which is physiological nonsense invented by someone with no idea how living animals work, or evidentally the basic laws of physics, pressure, hydrostatics and rheology…

Your next paragraph, however, seems to leap a great chasm of imagination. Having just stated that some large sauropods appear to have held their heads erect (given bone structure) but could not have had gigantic hearts or bone-splitting blood pressure you have two options:

1) Sauropods were aquatic

2) Sauropods were magic

You persist with option 2.

At this point in your argument you have simply assumed that large suaropods must be strictly terrestrial, but give no reasoning for this. Large sauropods probably came onto land now and then, like hippos do (and much like hippos they probably grazed low vegetation rather than browsed trees–one could imagine future paleontologists arguing that long extinct hippos were arboreal. It’s about the same level of silliness). Anyway, sojourns onto land would likely be enough for us to find sauropod footprints.

The argument about it being more efficient to browse up and down trees is lazy and poorly thought-out. This is because energy conservation would also be achieved by grazing over a large flat area, but even more so. As such you present another argument that is logically flimsy… consider the two possibilities:

– Sauropods could have compensated for high energetic costs of an erect neck by browsing up and down trees because this is energetically more efficient than walking large distances

– Or, sauropods could have avoided the high energetic costs of an erect neck entirely and achieved an even bigger energetic advantage by browsing over a wide area rather than walking large distances

Which is more likely? You ignore the second possibility entirely.

In the following sentence you have moved from a head ‘probably’ held aloft (assuming sauropod behaviour matched living amniotes, which remains an assumption) to ‘undoubtedly’… again without any reasoning supporting this jump (emphasis mine)… your article gives no reason for this change of view. You also characterize this as a wonderful feat rather than an implausible one, which would be much better scientific phrasing.

Again, I’m sorry, but your argument boils down to a series of dishonest quasi-logical statements, some hand-waving and a leap from ‘probably’ to ‘undoubtably’ without any application of critical thought.

Remarkably, you even identify a further problem that is created by the terrestrial head aloft theory (blood rushes to the head if lowered), and rather than stop and point out that by now the aquatic explanation is vastly more parsimonious, you invoke yet more magic physiology. It’s like sauropods just keep getting extra physiological bandages to fix yet another problem that appears, and all the while they become increasingly implausible.

There is nothing mysterious here. There is no wondrous mystery. There is no puzzle (except that educated people persist in holding to the idea that sauropods must have held their neck high because that’s how they’re drawn in children’s books).

It’s very simple:

– Small sauropods, a bit bigger than a giraffe, could have held their neck aloft on land. No big physical problem (no requirement for magic physiology).

– Large sauropds could have held their neck aloft when underwater (no requirement for magic physiology)

– Large terrestrial sauropods held their necks out and swept the necks over the ground to forage over a large area without having to move and/or without having to leave the safety of the water (no requirement for magic physiology).

For a comparison, consider how trees don’t use pressure to move water from ground level to their leaves. It just isn’t physically possible given biological systems. Some botany departments demonstrate this to students by having them set up a hose the same height as a tree and working out the pressure needed to bring the water up the tube. It is beyond the scope of a biological system. Moving water up tall building requires multiple pump rooms where water pressure is ‘reset’ in basins at intervals. I’m almost reluctant to point this out because no doubt now there will be a temptation now to argue that sauropods used evaporation and a chain effects of covalent HH bonds, as is the situation with trees, or they had ‘basins’ in their necks that reset blood pressure. This is the level of argument that paleontologists have resorted to. How this is still considered an argument at all is quite beyond me…

Anyway, I’m sorry for being critical, but a cornerstone of the scientic method is that when the evidence becomes overwhelming a scientist does not retreat into a forest of increasingly implausible arguments to protect a cherished theory.

Before proposing any more magic physiology you need to explain in cogent language why you think the most parsimonious hypothesis should be rejected (in essence, you need to explain why you think Occam’s razor is just plain wrong) and you need to explain why you are convinced that all large sauropods weren’t aquatic.

I’ll lay out the points again.

– Sauropods had long necks

– Bone structure in some (but not even the majority of) sauropods indicates an upright neck position

– But the blood pressure required would have been high enough to make sauropod heads literally explode

– And the size of the heart needed would have left no room for other organs in the body

Therefore:

– Large sauropods that held their necks aloft were mostly moving around underwater

– Or, large sauropods that held their necks aloft had a series of conjectural made-up adaptations that look like nothing on Earth and defy everything we know about living animals

As it stands, you pick the more complicated explanation and don’t attempt to address the simpler one. This simply isn’t good science.

This is written a bit quickly so there might be a few typos and errors.

Chris

Laelaps (@14): No slight to the AMNH intended, just a note that a controversy may resolve against the bold prediction and so render it into the “myth” category in the future. I, for one, find the rearing Barosaurus to be a highlight of the museum, however the science works out.

Nor would I slight anyone who can quote the inimitable dinosaur expert Miss Anne Elk in a discussion of Barosaurus and blood pressure.

On point 10…

From CGP Grey’s awesome 8 Animal Misconceptions:

Check out this cool Feathered Tyrannosaur found in China. http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2012/04/yutyrannus-huali-feathers/

@CPJ #21,

There is just one problem with your assertion that sauropods were aquatic. Water pressure would have collapsed their lungs, and their ribcages, at the depths where their necks would be erect.

Consider the giraffe, with a 2 meter neck. If he were to stand in the water with his head at the surface, as sauropods were long illustrated as doing, the pressure on his body would be about 200grams per square centimeter. We will estimate the surface area of the giraffes torso as about 2 square meters, making the pressure on his body 4000 kg, or the same as having 4 of his buddies standing on his chest while he tried to breathe. Now consider a sauropod at double or more that depth and pressure.

Also consider that the air pressure inside the lungs will be the same as the surface air pressure, while the blood pressure at the lungs will be increased by the external water pressure. If his ribs are strong enough to resist collapse, he will bleed out as his lungs hemorrhage. Unless, of course, there was some sort of magic physiology to prevent this.

While I can accept that Diplodicids, including Apatosaurus, were low feeders, the shape of Brachiosaurids’ bodies were more like a giraffe. Like giraffes, they were high feeders, and they dealt with blood pressure issues in a way that we don’t understand. YET.

Re: aquatic sauropods, why don’t we look at the sorts of habitats sauropods actually lived in? How many of them were found in wet palaeoenvironments with large bodies of water?

I’m grateful for that cladogram of Eumaniraptora, because it clearly marks Archaeopteryx as Sed. Incert., and it’s been worrying me for years that practically everything I read insists on it being an Avialan without ever explaining why, in the light od present knowledge, it’s still so considered. Well, OK, apparently it isn’t, or only as a possible candidate, which makes a load more sense. I wish the journalistic profession would catch up.

On #6 – just because mammals sometimes ate dinos doesn’t mean dinos weren’t also a major source of predation pressure on mammals. Today, small mammals (mice, rats, chipmunks) eat baby birds whenever they can; that doesn’t mean owls and hawks don’t also kill a lot of them. Everybody eats everybody, really.

What about this one, from lots of paleo art: “Dinosaurs were scaly and greenish-brown.” Probably not; see here: http://toughlittlebirds.com/2013/03/22/dinosaurs/

11. Humans and dinosaurs never lived together. (take that creationists!)

Number 8 is an interesting theory, but birds also lay eggs. There are no giant birds today, as there were in the past. There are no giant dragonflies like in the past either. Blue whales do not lay eggs, but somehow became the largest creature ever.

This egg laying theory is a non starter. Lots of species lay eggs today without growing to the sizes that their ancestors did.

On land, gravity is the ultimate limiter of size. There are no bipeds over 500 pounds alive today (except some humans, and they have problems with gravity). T-Rex does not appear to have had any problems running around on two legs, despite having the same mass as an elephant. And they keep finding even larger bipedal dinosaurs.

Something in the enviroment changed, reducing the maximum size of land animals over millions of years. Gravity seems to be the simplest explanation, and is backed up by geological evidence that the Earth has grown in size over the last 200 million years. An increase in Earth’s mass would cause an increase in the effect of gravity, which would make all land animals heavier. Whales would not be affected, as they live in the sea, which explains why whales are the largest life forms today, and in the case of the Blue Whale, ever.

I believe number 8 is completely wrong. The mass of the earth was much lower when the dinosaurs walked the earth which means that gravity was lower and allowed the dinosaurs to grow larger. Proof? The gains about 100 tons of mass every day from meteorites entering our atmosphere. Multiply 100 tons x 365 days x 100 million years = a very large amount of mass the earth has gained!

As far as T.Rex eating sauropod steak, it probably did eat dead, young, sick, or injured Alamosauruses, but the size difference meant that T.Rex would have generally lost a fight to a healthy adult. In spite of my nitpicking, though, great post! Doesn’t matter if I’m 13, 23, or 83, I’m always going to love dinosaurs.

I have a question. If dinosaurs lived millions of years ago. Why is there evidence of human footprints and dinosaur footprinta together?

Brontosaurus was not a thing. Myth Busted. Brontosaurs are back, baby!

(Hey, that would make a great film title).

“Wait, doesn’t 10 contradicts 2? Do birds actually evolved from flying archosaurs instead of dinosaurs?”

No, birds came from dinosaurs. There were actually two separate archosaur lineages that evolved flight independently – first the pterosaurs evolved flight, and then a subfamily of dinosaurs did.

Actually birds existed with dinosaurs, there is no archeological evidence to support the assumption they were ever related to birds, they have tried to say there are dinos with feathers but those were frauds, frayed pieces of tendon they called “proto feathers,” And literally modern looking birds are found in rock layers the same and supposedly older than dinosaurs, the geologic collum that they somehow date the fossils by….by the rock….by the fossils… all of that is false. Also the oxygen level would have to be higher to sustain giant creatures, its part of the reason they died out to begin with, not some retarded comet that somehow killed all of them but conveniently not much else, stupid idea.

jts said:

Please DO the math:

Even if such thing happens now the mass of the Earth will increase a little bit:

100,000kg/day × 365days/year × 100×10^6years = 3.65×10^15 kg

If we add this to the mass of the Earth then you get:

5.972 × 10^24 kg + 3.65×10^15 kg = 5.972000004 × 10^24 kg

This is a neglible increment of 0.000000061%.

1. Humans have ALWAYS lived with dinosaurs. We call them “birds.”

2. The mass of the Earth was not “much less in pre-historic times.” I can’t even begin to address that sort of nonsense. The gravitational pull was the same then as now.

3. Sauropods were not aquatic. That’s absolute rubbish.

4. Latest set of papers point to the sauropods’ necks themselves solving the blood-pressure issue. Quite neat. :-)

Kyle, your comments are contradicted by every bit of scientific evidence. You need to go take some 400-level college courses in various topics about and related to Paleontology. Please, for your own dignity, don’t post that nonsense anywhere again.

A couple things about dinosaurs that have annoyed me for years. First… setting aside the fact that everyone is still searching to find someone still left to surprise (and hopefully awe) with the old “Dinosaurs are all around us, they’re birds!!” line. Not so easy these days, its old news. But the whole business imo is just an exercise in confusion.

We know now that birds existed in the Cretaceous, alongside dinosaurs… and those animals we still call ‘birds’. Because of course, we recognize them as birds, not dinosaurs. The same goes for today: when any family takes their kids ‘to see the dinosaurs’ they don’t go to a chicken farm or go out to feed the pigeons, unless they expect some very grouchy and disappointed kids. They take them to see dinosaurs.

We even take this to extremely silly levels by saying certain dinosaurs ‘look like a bird’, or a bird may ‘resemble a dinosaur’. Lets just hang up the shenanigans already, and go back to calling birds birds, and dinosaurs dinosaurs, because we already are… and always will. After all they’re only labels we created ourselves.

The second development that has really bothered me is the whole tails-in-the-air, balancing act that of course Jurassic Park made mainstream as it were. Yes we know dinosaurs didn’t drag their tails now. However this is frequently taken to the extreme, with the animal standing completely vertically as if it simply were a four-footed animal that chanced to have shorter front legs.

Common sense proposes this- why then, stand on two legs at all? Surely they did so to raise their head as high as possible, to get a better vantage point to see prey and predators, and/or find food. A simple look at present day dinosaurs (or birds?) will show you that most terrestrial birds crane their necks and hold them to the skies- ostriches, emus, chickens, you name it. There isn’t one land walking bird (or dinosaur??) today that walks with its head and tail parallel with each other, hunched over like a caveman.

Thoughts????

dinos sometimes have feathers and spinosaruases walk like crocs and aligator so i say to that myth see ya later aligator in a while crocidile

@39 There were actually two separate archosaur lineages that evolved flight independently – first the pterosaurs evolved flight, and then a subfamily of dinosaurs did.

Two separate lineages, but at least three separate independent evolutions of flight: there were flying feathered dinosaurs that were unrelated to birds.

big dinosaurs did not have butt brains and stegosaurus had a walnut sized brain. and the tr-x hands were not wimpy they where made to scrach with.and some of the dinosaurs where small for exzample Protoceratops was small.ther is no achent wrold we live on the land that dinosuars lived on.