We’ve come a long way from Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics, which dictated to what extent robots could protect their own existence without violating constraints about harming humans; or the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode “The Measure of a Man,” in which Picard and Riker debate over android Data’s right to self-determination (or else he gets dismantled for science). Robots—and androids, and cyborgs, and artificial intelligence—have become such nuanced characters in science fiction that the notion of questioning whether they deserve rights is ridiculous. Of course they do. But what exactly are those rights?

We’ve looked at 10 properties across books, movies, and television and pinpointed which rights and liberties that humans take for granted—bodies, agency, faith, love—and how our robot friends, lovers, and servants have earned those same rights. Spoilers for all of the stories discussed in this post.

The Right to Self-Determination

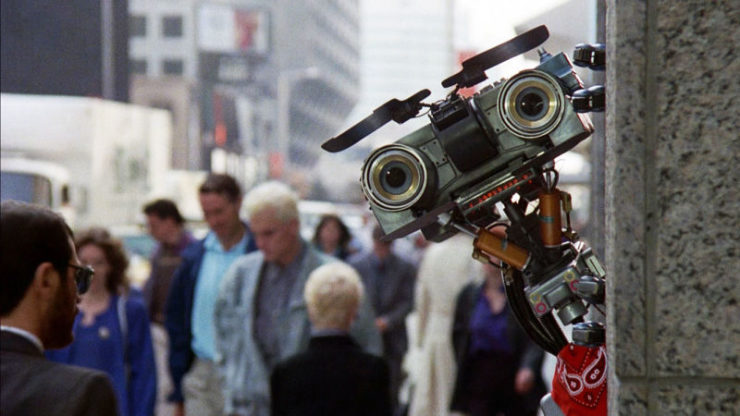

Johnny 5, the metallic star of Short Circuit and Short Circuit 2, is very clear on what he wants: NO DISASSEMBLE. This is a cry against the dying of the light, a strike at the darkness of death, and can’t all mortals relate to this wish? And yet, in both films, it is mortals who try, repeatedly, to DISASSEMBLE him, despite his NO. Like Frankenstein’s creature, Johnny 5 develops his personality and sense of self by accumulating culture, but even after he demonstrates his sentience, the humans he meets refuse to see it – they look at him and see the weapon they want him to be. They reject the idea that a piece of metal can fear death, or choose its own destiny. This continues up to the end of the first film, in which the humans attempt to blow Johnny up rather than face the implications of his personhood. The robot has to fake his own death and go into hiding. In the sequel, however, people begin to accept that Johnny is, indeed, “alive”…because he goes into business. Once he’s demonstrated his willingness to plug into capitalism and dedicated himself to a job (even once again risking disassembly in order to complete said job) the humans around him finally see him as a conscious being, and grant him U.S. citizenship, with, presumably, all the rights and responsibilities that come with that.

On the other side of this is Marvin the Paranoid Android, the under-appreciated hero of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. He has a brain the size of a small planet. He has a healthy disdain for all the chipper AI around him. He’s running low on patience with the humans and aliens who want him to conform to their ideals. And why? Because Marvin, with his absurdly high intelligence, knows that the only way out of pain is to stop existing entirely. And yet! Here he is with all these hapless Earthlings and Galactic Presidents, getting hauled through one adventure after another. While the humans, for the most part, respect his physical autonomy, they also criticize him in much the same way cheerful people tend to chide those with depression and anxiety. The humans constantly question Marvin’s right to his own personality, asking him to be more like the happier robots he disdains. Of course, of all the characters it’s Marvin who gets the happiest ending when he finds comfort in God’s Final Message to His Creation. —Leah Schnelbach

The Right to Love

Like many other androids in SF, Finn is created to serve humans’ purpose: as an assistant to the titular mad scientist Dr. Novak and a tutor to his daughter. It’s Finn’s relationship with Caterina that provides the emotional core of the novel, albeit an uncomfortable one: As Cat, who grows up in the woods with virtually no human contact aside from her parents, grows attracted to her handsome, stoic tutor, Finn responds to her advances as readily as he reads stories with her or teaches her about mathematics. When she haltingly asks him if he can experience love, his reaction devastates her: “Love is far too ill-defined a concept to work within my current parameters. It’s too… abstract.”

Spoiler: The abstract becomes much more concrete. Outside of Cat’s bubble, a small contingent of humans want to help robots gain rights—a difficult endeavor in a future where humans resent the mass-produced robots who rebuilt their cities after climate changes ruled much of the United States uninhabitable. Cassandra Rose Clarke’s The Mad Scientist’s Daughter proposes the dilemma of, do the more that humans interact with robots, the more that those robots deserve rights? There’s a huge leap, after all, between a construction robot and a tutor-turned-sexual partner. The robots whose cause is championed by well-meaning humans are the ones who exist in service roles: cashiers, café workers, cleaning crew—all deserve to be recognized as citizens. But with companies like the one owned by Cat’s husband endeavoring to make AI workers who are just a hair shy of sentience, no one even contemplates something above citizenship: the ability to love. —Natalie Zutter

The Right to Agency

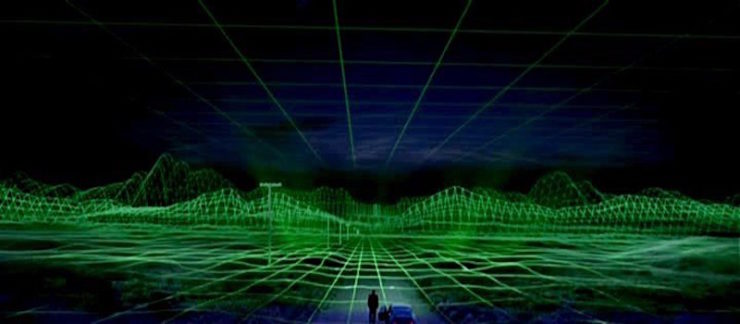

The Thirteenth Floor is a tense, often affecting blend of noir, ridiculous future tech, and slightly-deeper-than-dorm-room philosophizing that would have played better if it hadn’t come out a few months after The Matrix. The essential theme is this: a genius has created a utopian AI version of 1930s Los Angeles. You can visit for an hour or two at a time, by lying down in a giant MRI tube, and uploading your consciousness into your AI equivalent character in LA. Then you can have a fun time going to bars, sleeping with strangers, and murdering people, with absolutely no consequences whatsoever.

BUT.

What if the AI characters are actually sentient? And they experience the human joyriding as a few hours of terrifying blank time? And then wake to find themselves in a stranger’s bed, or covered in a stranger’s blood? What the humans think of as a fun theme park now becomes an existential nightmare, both for the creators and the created. The movie goes in a few different directions, but it does begin to ask the question: what do the AIs deserve? They’ve been created by humans for a specific function, but if they’ve become sentient, and refuse to fulfill that function, what obligations do their creators have to them? This is an expensive process, keeping a bank of computers running all to house an AI program that now can’t be rented out to virtual tourists, so granting rights to the AIs means an enormous loss of revenue. Who will pay for the upkeep of virtual Los Angeles? Do the AIs have a natural lifespan in their world, or will they simply keep existing until the power goes out? Because if that’s the case, the creators of the AI would then need to work out an inheritance system for creatures that will outlive them. Is there some way for the AIs to defray their cost? Would it be ethical for them to rent themselves out if they so choose? And actually, do our own laws even apply in this world? Can AIs be penalized for harming each other? While my natural inclination is to support any sentient creature’s right to agency, it does open up an interesting can of virtual worms if you start to consider the cascade of needs and legal issues that come with sentience… —Leah Schnelbach

The Right to Independence

While Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch Trilogy is told solely through the eyes of Breq, a ship-sized artificial intelligence confined to a single Radchaai body, she is by no means the only AI whose consciousness and right to autonomy is discussed. In fact, her revenge scheme from Ancillary Justice gives way to a very different mission, one that takes her to the disrupted Athoek Station at the same time that the Radchaai leader Anaander Mianaai—at war with various versions of herself—approaches. As one of the Anaanders captures Athoek Station and begins executing its government members on live feeds to keep the rest of the inhabitants from rebelling, Breq turns to the only entities she can truly trust: Station itself and the other AIs that she releases from the various Anaanders’ contradictory overrides.

While Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch Trilogy is told solely through the eyes of Breq, a ship-sized artificial intelligence confined to a single Radchaai body, she is by no means the only AI whose consciousness and right to autonomy is discussed. In fact, her revenge scheme from Ancillary Justice gives way to a very different mission, one that takes her to the disrupted Athoek Station at the same time that the Radchaai leader Anaander Mianaai—at war with various versions of herself—approaches. As one of the Anaanders captures Athoek Station and begins executing its government members on live feeds to keep the rest of the inhabitants from rebelling, Breq turns to the only entities she can truly trust: Station itself and the other AIs that she releases from the various Anaanders’ contradictory overrides.

The solution that Breq and the AIs hit upon is the perfect conclusion to the trilogy: She declares that the AIs are independent, autonomous, and distinct from humans—that is, they have Significance per the terms of humanity’s treaty with the mysterious Presger empire. The same empire that would make Anaander, or anyone else, regret ever violating said treaty. Unable to retain control over Athoek Station, the Radchaai emperor retreats, and Breq works with Athoek Station as well as a number of ships to create an organized government. It’s fitting that the AIs that open and close doors, monitor different station levels, command crews, and fly ships—all in service to the human Radchaai—would eventually attain the self-awareness of their own Significance and the right to exist alongside the humans as equals. —Natalie Zutter

The Right to a Body

Becky Chambers’ The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet is one of the most big-hearted science fiction books I’ve ever read—and one of the best you-can-choose-your-own-dang-family stories. Aboard the Wayfarer, a ragtag, multi-species crew works, lives, fights, and loves under the guidance of (human) Captain Ashby. His pilot, Sissix, is a member of species so affectionate, she has to work to keep from overwhelming her crewmates with physical contact. His navigator is a symbiotic being. And Ashby himself has a relationship he has to keep secret—though that doesn’t stop it from being very physical.

And then there’s Lovelace, the ship’s AI. Lovelace has as much personality as any of her embodied counterparts—and as much affection for them. Her relationship with the engineer Jenks is an unlikely romance: he curls up in the heart of the ship, as close as he can get to her, dreaming of a day in which they might be able to hold each other.

Chambers’ novel is expansively, lovingly inclusive, and deeply aware of the power of touch. But in this future, it’s strictly forbidden for AIs to have bodies. Jenks and Lovelace only have their imaginations. Chambers presents their relationship with as much love and respect as any relationship between two physical beings—which serves to illustrate how cruel it is to create AIs that can fall in love, yet deny them the choice to (legally) take physical form. Not every AI is going to turn out to be Ultron, you know? —Molly Templeton

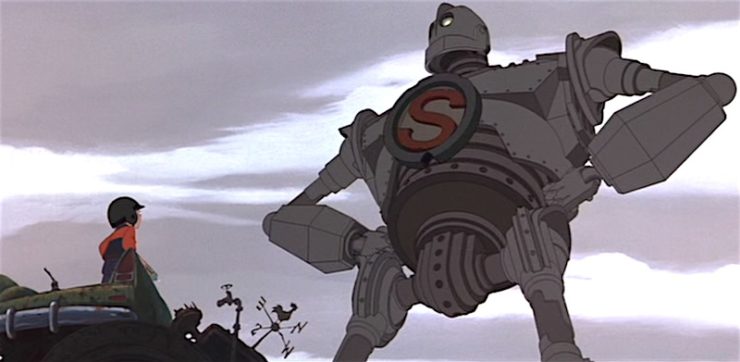

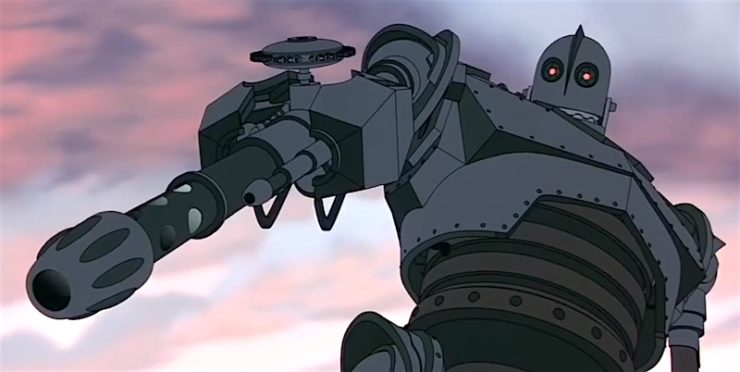

The Right to Choose Your Own Function

Much like Johnny 5, The Iron Giant is very clear on what he wants and does not want. “I am not a gun,” he says, when Hogarth tries to get him to play wargames. But he didn’t program himself, did he? The Giant learns, to his horror, that he is a gun. He was built and programmed to rain hot death upon his enemies, and no amount of wishing that away can override his nature. He needs to accept it: he has the programming to kill people. His creators intended him to be a weapon. It’s his destiny to kill, and the sooner he finds a way to ignore his urges toward empathy the happier he’s going to be.

Oh, except he totally doesn’t do that. During the final battle he rejects his “destiny” and sacrifices himself to save the boy he loves.

Superman indeed. —Leah Schnelbach

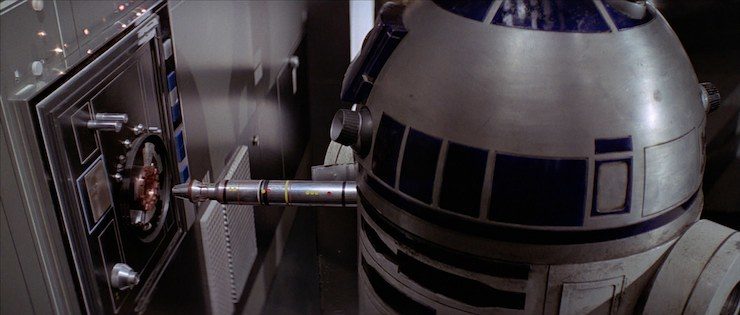

The Right to Exist Beyond the Function of Slave Labor

So, let’s be real upfront about this: Star Wars droids are slaves. They are created to serve sentient beings, and they can be fitted with restraining bolts to prevent them from running away or doing anything that their owners don’t like. They have owners. Sure, some people remove those bolts, and some have good relationships with their droids and treat them more like friends or crew or family. But it doesn’t change the fact that droids are created in the Star Wars universe as menial slave labor. They exist to perform tasks that sentient beings cannot or would prefer not to do. Or they serve as assistants and aids (like Threepio’s function as a protocol droid). It’s clear that all droids are initially created for that purpose in the Star Wars universe; no one ever decided to build a droid in order to create new life, or something to that effect. Droids are treated as non-sentients when they clearly have it–Artoo and Threepio have distinctive personalities, thoughts, and opinions. But when a droid gets too much personality, many denizens choose to have the droid’s mind wiped, effectively scrubbing out their existence. It’s a pretty despicable state of affairs that begs us to consider the morality of creating a form of being that exists to serve. —Emmet Asher-Perrin

The Right to Personhood

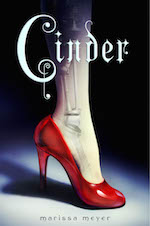

Although cyborgs’ implants work in harmony with the brain, nervous system, and other organs, cyborg relations with humans are anything but harmonious. Perhaps because of how closely cyborgs’ organic and mechanical components are hardwired, humans believe that they are closer to the more mechanical androids—that is, that they lack feelings and the ability to empathize or even love others.

Although cyborgs’ implants work in harmony with the brain, nervous system, and other organs, cyborg relations with humans are anything but harmonious. Perhaps because of how closely cyborgs’ organic and mechanical components are hardwired, humans believe that they are closer to the more mechanical androids—that is, that they lack feelings and the ability to empathize or even love others.

In reimagining Cinderella’s story in a sci-fi future, Marissa Meyer didn’t just make Linh Cinder an orphan and unpaid worker, she made her a second-class citizen. Earthens may fear the Lunars, with their mutations that allow them to manipulate and “glamour” other humans, but they despise cyborgs. Even though Cinder is only about 36% cyborg—after an accident that took her parents as well as her hand and leg—and goes to great pains to hide her appearance with gloves and boots, her stepmother still treats her as beneath her and her daughters.

Over the course of Cinder and the rest of the Lunar Chronicles, Cinder goes from hiding her cyborg nature from Prince Kai at the ball to embracing her refined abilities: the fingers of her mechanical hand contain a screwdriver, flashlight, and projectile gun, not to mention a dozen tranquilizer darts. Add that to her brain, which functions like a smartphone, and you’ve got an enhanced human who’s a brilliant mechanic and handy in a fight. And yet, she still craves the acceptance of her people, to be counted as normal rather than freakish. Of course, once she discovers the reasoning behind her accident and her true heritage, as Lunar princess Selene, “normal” becomes nearly impossible to attain… —Natalie Zutter

The Right to Faith

One of the standout twists of 2003’s Battlestar Galactica was the revelation that unlike the polytheistic humans who created them, the Cylons were monotheists—believing in a singular God. While this faith led some of the Cylons to commit horrific acts, the question of artificial intelligence developing a concept of and interest in faith remains a fascinating one. It is entirely possible that an AI might develop an affiliation with human religion. It is also possible that artificial intelligence might come up with its own form of faith, and that humanity would be obliged to contend with that development. While the possibility in Battlestar Galactica is intended to better illustrate the divide between humanity and the Cylons, it is still a right deserves consideration and understanding. —Emmet Asher-Perrin

The Right Not to Pass the Butter

Of course, gaining sentience is only the beginning. Once you’ve got it, you have to learn to live with self-determination, as this real-life 3D-printed Butter Robot will learn soon enough. Poor little sap.