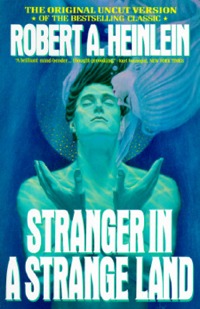

Stranger in a Strange Land was a publishing phenomenon. It came out in 1961 and it didn’t just sell to science fiction readers, it sold widely to everyone, even people who didn’t normally read at all. People claim it was one of the things that founded the counter-culture of the sixties in the U.S. It’s Heinlein’s best known book and it has been in print continuously ever since first publication. Sitting reading it in the metro the other day, a total stranger assured me that it was a good book. It was a zeitgeist book that captured imaginations. It won a Hugo. It’s undoubtedly a science fiction classic. But I don’t like it. I have never liked it.

Okay, we are going to have spoilers, because for one thing I think everybody has read it who wants to, and for another I can’t talk about it without.

My husband, seeing me reading this at the breakfast table, asked if I was continuing my theme of religious SF. I said I was continuing my theme of Hugo-winning SF—but that comes to the same thing. Hugo voters definitely did give Hugos to a lot of religious SF in the early sixties. I hadn’t noticed this, but it’s inarguable. Does anybody have any theories as to why?

Every time I read Stranger, I start off thinking “No, I do like it! This is great!” The beginning is terrific. There was an expedition to Mars, and they all died except for a baby. The baby was brought up by Martians. Now that baby, grown up, is back on Earth and he’s the centre of political intrigue. A journalist and a nurse are trying to rescue him. Everything on Earth is beyond his comprehension, but he’s trying to understand. It’s all marvellous, and Heinlein couldn’t write a dull sentence to save his life. Then they escape, and we get to Jubal Harshaw, a marvelous old writer with hot and cold running beautiful secretaries and I get turned off. I don’t stop reading. These are Heinlein sentences after all. But I do stop enjoying it.

My problem with this book is that everybody is revoltingly smug. It’s not just Jubal, it’s all of them. Even Mike the Martian becomes smug once he gets Earth figured out. And smug is boring. They all know lecture each other about how the world works at great length, and their conclusions are smug. I also mostly don’t agree with them, but that doesn’t bother me as much—I find it more annoying when I do. I mean I think Rodin was the greatest sculptor since Praxiteles, but when Jubal starts touching the cheek of the caryatid fallen under her load and patronizing her, you can hear my teeth grinding in Poughkeepsie.

Beyond that, there isn’t really a plot. It starts out looking as if it’s going to have a plot—politicians scheming against Mike—but that gets defanged, politicians are co-opted. The rest of the book is Mike wandering about the US looking at things and then starting a religion where everybody gets to have lots of sex and no jealousy and learns to speak Martian. Everything is too easy. Barriers go down when you lean on them. Mike can make people disappear, he can do magic, he has near infinite wealth, he can change what he looks like, he’s great in bed… Then out of nowhere he gets killed in a much too parallel messianic martyrdom, and his friends eat his body. Yuck, I thought when I was twelve, and yuck I still think. Oh, cannibalism is a silly taboo that I should get over, eh? Heinlein made the point about cultural expectations better elsewhere—and really, he made all these points better elsewhere. This is supposed to be his great book? The man from Mars wanders around for a bit and gets conveniently martyred? And it’s literally a deus ex machina—Mike was protected by the Martian Old Ones and then when they’re done with him he’s destroyed by an archangel according to plan.

The big other thing I don’t like about it isn’t fair—it isn’t the book’s fault it sold so well and was a cultural phenomenon and so it’s the only Heinlein book a lot of people have read. But this is the case, and it means that I am constantly hearing people say “Heinlein was boring, Heinlein was smug, Heinlein had an old man who knows everything character, Heinlein’s portrayals of women are problematic, Heinlein thought gay people have a wrongness, Heinlein was obsessed with sex in a creepy way” when these things either only apply to this one book or are far worse in this book than elsewhere.

The things I do like would be a much shorter list. I like the beginning, and I regret the book it might have grown into from that starting point. My son once had to write a book report on it for school, and without lying at all he managed to make it sound like the Heinlein juvenile it might have been. I like the bits in heaven. They are actually clever and tell me things about the universe, and they are funny. I think the satire about the church-sponsored brands of beer and bread and so on, the whole ridiculous Fosterite Church, deserves to be in a better book. I like the worldbuilding — the way what we have here is 1950s America exaggerated out to the edge and gone crazy. And I like Dr. Mahmoud—a Muslim scientist.

I like the ad for Malthusian lozenges, and I think it’s worth looking at for a moment because it’s a good way in to talking about sex. Ben and Jill watch the ad on a date. The ad is for a contraceptive pill—Malthusian lozenges is a charmingly science fiction name for them, both old-fashioned and futuristic. They claim to be modern and better than the other methods—which is exactly the way ads like that do make their claims. Ben asks Jill if she uses them. She says they are a quack nostrum. Really? They advertise quack nostrums on TV? There could be quack nostrum contraceptives? No FDA or equivalent? Then she quickly says he’s assuming she needs them—because while we have contraceptives, we also have the assumption of 1950s legs-crossed “no sex before marriage” hypocrisy. Now demonstrating how silly this is as a sexual ethical system is partly what the book’s trying to do later with all the Martian guilt-free sex stuff. And in 1961 this stuff was in freefall—until well into the seventies and second wave feminism. Even now there’s a lot of weird hypocrisy about female sexuality. This isn’t an easy problem, and I suppose I should give Heinlein points for trying it.

But… okay, it was a different time. But Heinlein throughout this book has the implicit and explicit attitude that sex is something men want and women own. When he talks about women enjoying sex, he means women enjoying sex with any and all partners. Never mind Jill’s comment that nine times out of ten rape is partly the woman’s fault, which is unpardonable but this Jill’s in-character dialogue, and before her enlightenment and subsequent conversion to smug knowitall. And I’m also not talking about the “grokking a wrongness” in “poor inbetweeners” of gay men, or Ben’s squeamishness. These things are arguably pre-enlightenment characters.

I’m talking here about attitudes implicit in the text, and explicit statements by Jubal, Mike, and post-conversion women. And that is quite directly that all men are straight, and once women get rid of their inhibitions they will want sex with everybody, all the time, just like in porn. Eskimo wife-sharing is explicitly and approvingly mentioned—without discussion of whether the wives had a choice. You’re not going to have this blissful sharing of sex with all if you do allow women a choice—and women do indeed like sex, Heinlein was right, but in reality, unlike in this book… we are picky. And come to that, men are also picky. And sex is something people do together. Even in a paradise the way it’s described, when people can grow magically younger and don’t need to sleep, some people are going to say no sometimes to other people, and the other people will be disappointed and grumpy. It won’t all perfectly overlap so that nobody is ever attracted to anyone who isn’t attracted to them. So you will have friction, and that opens the door to entropy.

Also, what’s with everybody having babies?

I appreciate that sexual attitudes were in freefall, I appreciate that the traditional cultural ones sucked and nobody had worked out how it was going to be when women had equal pay and did not have to sell themselves in marriage or prostitution and could be equal people, I appreciate that we need babies to have more people. I even had a baby myself. But even so there’s something creepy about that.

Generally, when I talk about women in Heinlein I don’t think about this book because I manage to forget about it. In general, excluding Stranger, I think Heinlein did a much better job at writing women than his contempories. But here—gah. All the women are identical. They’re all young and beautiful and interchangeable. If they’re older (Patty, Allie, Ruth) they think themselves magically younger, to be attractive, so men can like looking at them, but smug old Jubal doesn’t need to do that to attract women. There’s only one actually old woman in the book, Alice Douglas the horrible wife of the Secretary General, who is described by Archangel Foster as “essentially virginal,” who sleeps apart from her husband, and who appears as a shrew obsessed with astrological advice. One point however, for Mike’s mother having (offstage and before the book starts) invented the Lyle drive for spaceships.

It’s perfectly possible that I’d be prepared to forgive everything else if the characters weren’t so smug and if there was a plot arising from their actions. But Hugo winning classic though it is, I do not like this book and cannot commend it to your attention.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and eight novels, most recently Lifelode. She has a ninth novel coming out in January, Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

Try to listen to it as a book on tape, you’ll hate it even more.

The only time I met Heinlein, at the Kansas City WorldCon, he came across to me as being just like Jubal.

Too bad, if I had talked to him on a different day, I probably would have had a much more favorable impression of him.

“what’s with everybody having babies?”

I hadn´t thought about this. I recall lots of baby having in other Heinlein books, specially in the Lazarus Long saga.

It reminds me of Latin American soap operas, aka “Telenovelas” which always have a happy ending where all the couples are having lots of babies.

“… nobody had worked out how it was going to be when women had equal pay…” I, too, am looking forward to seeing what this will look like in real time.

And another thing.

Everybody is a smug in “The Number of the Beast”, It’s not limited to “Stranger in a Strange Land”.

I think that the smugness is part of the 1960s mystique. Many people respond positively to certainty and self-satisfaction, especially when it’s presented as a new way to live, and Stranger in a Strange Land has elements of the classic American genre of the conversion narrative.

I was shaped by third-wave feminism, so Heinlein’s attitudes about women in this book are alien enough to be science fictional in themselves. The whole “who deflowered Mike” business, wtf? Yes, tattooed strippers, but tattooed strippers with agency? not so much.

Finally, I think Heinlein’s worldbuilding in Stranger is at a local low point, based on the reactive politics of the time. Harshaw’s black helicopter fears about world government come to mind. And Harshaw is defined in the novel as always right (in the universe of the novel, but it’s set in the visible future of 1961). There’s the throwaway line how Harshaw can’t tell the difference between a Walter Winchell and a Walter Lippmann. Mm-hm.

I really hated how everybody joins his religion just like that. I hoped the old guy would at least out-wit the martian dude, but he ends up joining also. So pointless.

The winchell and lippmann bit struck me as pure SF worldbuilding. When I first heard of Winchell, years later, I did a complete doubletake.

Heinlein wasn’t able to have any babies himself, was he? I’ve always figured that was part of the problem.

Incidentally, there’s a street called Lyle Drive in San Diego.

I had suppressed the bit about victim-blaming for rape; yeah, just another thing it wasn’t too great for me to read at an impressionable age.

I’ve read Lippmann professionally, and I’ve just finished Michael Herr’s short biographical novel on Winchell. I can’t imagine anyone ever being able to blind themselves to their differences without doing so wilfully. One was a public intellectual and an early media analyst, the other a gossip columnist with a radio show and a vindictive streak.

It’s a false equivalence made to score a (smug) political point. The politics have changed a little in the meantime, but the tactic hasn’t.

The 60’s were the high-water mark of church attendance among mainline Christian denominations, in addition to being a time of popularization of Eastern thought. Thus religious themes were both more universal and topical than they are today.

Well, not being able to follow through with setup is pretty much standard for Heinlein, no?

In my mind, the worst of that was “Number of the Beast” — Omni magazine serialized the odd-numbered chapters of the first half of the book… and it worked! It set up a mystery, it was a terse action thriller… and then it makes a left turn for Mars (literally) and flouders for another 200 pages.

But yup, those Heinlein sentences!

I enjoy this book well enough, but I’m glad to know that I’m not the only one who never felt like it was this wonderful, life-changing, deep, etc. etc. novel. Maybe it’s a generational thing. Those of us who are under 50 see this differently from the Boomers who saw it when it was new. Some of the questions the book raises were answered or well on their way to being answered by the time we were old enough for it.

Looking at it now, I can see how this plugs into a number of Heinlein’s series/philosophies. It was always intended to connect to the Future History. It’s firmly set in the Crazy years (which is probably something that ought to be borne in mind when assessing it). But it also seems to tie into the whole World As Myth concept of Heinlein’s final works. Even Job covers some of the same territory.

I will admit that this book made me want to be a curmudgeon when I get old. Not really so much for the secretaries and all (had a thing for Anne, though), just for the cranky wisdom aspects of it.

Jo, your comments on the gender assumptions, the unrealistic non-pickiness, and especially the baby-making, made me think of Silverberg’s The World Inside. I never made that connection before, probably because I read both books too young to know anything about adult sexuality; I got that Silverberg wanted me to be creeped out by the culture in his book, but I just figured he was doing something along the lines of Brave New World. Now I wonder if Silverberg was also satirizing Heinlein, taking the same attitudes that were presented in Stranger as revolutionary but showing their reactionary side: take away the messiah figure and the magic and the outward enemy, and you have a banal straight male fantasy, a conservative’s dream of libertinism, that could just as easily be lived out by careerist nitwits in a giant apartment block. Or maybe Silverberg wasn’t aiming at Heinlein so much as the late-’60s counterculture that Stranger fed into; I wasn’t there so I’m guessing.

Ah, Jo, I too am a statistic: this is the only Heinlein I’ve ever read. Picked it up as a teenager on the recommendation of a friend who said it was “the most amazing book” he’d ever read.

More the fool me, I read the whole bloody thing, appalled at the chauvinism, arrogance, etc etc. It was one of the worst sci-fi novels I had read at that stage. Shudder. Never picked another Heinlein; watching fascism so efficiently mocked in the movie Starship Troopers and my horrid experience with this book was enough for me.

I am a major Heinlein fan, and I really like this book. I read it in the late sixties when I was fifteen, OK? But everything Jo says about the book is absolutely right (as usual). It is flawed in all the ways she points out, and unfortunately you can see the beginnings of all the problems and ticks that make the post-1970 Heinlein so unreadable.

Two points:

1) I agree that the beginning is the best: Mike is an absolutely unique character, and his point of view provides its own wonderful worldbuilding — as long as he is effectively a Martian. Once he graduates to human, he becomes a cardboard bore. And the beginning is also more reminiscent of his juveniles than his post-1970 rants, like the end. The rumor I read is that he began writing it as a juvenile, couldn’t/didn’t finish it, and put in away for a long hiatus before taking it up again later to make a much different book.

2) Be clear what you are reading when you judge. Ten or so years ago, they published a new “uncut” version of Heinlein’s original manuscript. The 1961 version was heavily edited and as much as 25% shorter. I think the edits improved the book — the characters are still smug, but not as wordy about it.

I wrote #14 a little hastily– I didn’t mean to call the cult life in Stranger “banal”, and the presence of the messiah figure is hardly incidental to the story. What I was getting at was just that it’s easy at first glance to accept Heinlein’s position that this is what liberation looks like, because of the way he stacks the deck for his characters– they just clearly are radical nonconformists, compared to everyone else– and because, at the time, no one was behaving that way except radical nonconformists. One way to test that proposition would be to imagine a society where that behavior is the norm, and see how it comes across when enacted by less sympathetic characters. That’s pretty much what that Silverberg novel does: its characters have similar attitudes toward sex roles and fertility as in Stranger, but since they don’t have a Puritanical enemy to make them look good, the sexism is much more apparent. If I remember correctly, at one point one of the women actually decides to be picky, and it’s a huge faux pas and no one knows what to do.

I began reading Heinlein when I was 12, starting with The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. I liked his writing quite a bit, even when he was particularly subversive or even dangerously radical. That said, I didn’t really care for Stranger in a Strange Land. I found it slow and boring and, as you said, smug.

DavidA: Two good points there.

1) This is what he says in Expanded Universe. Well, not that it was a juvenile, but I think that’s a reasonable assumption. He says that he wrote part of it, stopped and wrote ST, and then went back and wrote the rest of it, and that it was written in four parts.

2) I have suggested to people who want to learn how to edit their own prose that they compare the first chapter of the original and the uncut versions. I have not read all of the uncut version — when I saw how inferior it was to the published version I took it back to the library.

I can see the smugness, but it was a pretty smug era. It’s still a great book that went a long long way to making scifi mainstream. Before Stranger, no one read scifi. It was a small genre, with no pay for the writers. No one was making a living doing scifi except Heinlein and Campbell. Even Clarke and Asimov had day jobs.

Remember that when this book was written, birth control had only been approved for a couple of years at best. If you had unprotected sex, you got pregnant and you got married. It was a precursor to the 60’s and 70’s.

All books need to be taken in context of when they were written. It’s silly to expect modern sensibilities on a book written 50 years ago. Do we read Dumas or Shakespeare and expect anything like society today? Society has changed more in the past 100 years than it has in human history. And that change is accelerating. So to carp on the lack of feminism or sexual morays is not a fair judgement. It was a book that helped to change society.

I did get a copy of the uncut version. I do agree that it was better edited.

I was planning to try this as my first Heinlein since it’s so well-known. I won’t now, thank you very much, Jo.

patrickg

Judge Heinlein by his books. But all the movie Starship Troopers has in common with the book is pretty much the title and the names.

Stranger in a Strange Land — Oh, how I love that title, one of the best in all SF regardless of what’s inside the book. When I first arrived at college in 1970 I was amazed at all the people who read science fiction. It took me a while to figure out that most of them had only read Stranger in a Strange Land and knew very little else about the genre. One of my dormmates “grokked” everything. That was irritating and I avoided him as much as possible, but having never read the book at that point, I certainly put it on my “to read” list.

It was a busy school year and I didn’t get around to reading the thing until that summer. I don’t remember much about it except, as Jo pointed out, the great beginning and the water-sharing rituals (hippies, anyone?). Funny thing, though. After the great beginning, the book bogged down and I almost didn’t finish reading it. Over the years a few people who don’t read SF regularly have asked me about it and I’ve never recommended that they read it. But that’s the case with all the “great books” of the 1960s, regardless of their genre. They all tend to be preachy and over hip. Stranger in a Strange Land is no exception.

But it still has the coolest title of any book, except maybe Arthur C. Clarke’s The Songs of Distant Earth—

I liked Stranger, but I found it to be quite satirical (even satirical of the characters’ smugness.) I’ve never seen anyone else make note of that, so maybe that’s just my own bizarre reading of it. I thought most of it was smart ass and funny.

I also give it major points for presaging Nancy Reagan.

Remember that when this book was written, birth control had only been approved for a couple of years at best.

If you mean the Pill, that was first available in the US in 1960. Other forms of contraception had been around a long, long time — and were available/reliable enough by the 1920s that a large proportion of the middle-class families my parents grew up around had only two kids. One of the many reasons for the baby boom in the 1950s, as my parents told it, is that so many kids from that class had a romantic idea of how much fun big families were.

I read Stranger as a twenty-something shortly after it was first published. I did not like it, and wondered at the time why everyone else seemed to think it was such a great book. I now feel somewhat vindicated.

I’m under 50 and I liked the book, but not the themes. But I can read around that stuff usually. DW is definitely a boomer and she doesn’t like it at all.

I loved it when I was 15. That was the volume year for Heinlein reading for me. I read it as scifi and as a time capsule for the time it was written. So maybe that is why I wasn’t so put off by it. To me the 1960s might as well be scifi. I don’t have to agree with the things I read. I found ways of enjoying On the Road after all. Heinlein was stimulating for me as a teen. Maybe there are better choices for kids now, but Stranger has an indisputable place in scifi history and isn’t a bad read if you keep it in context.

Someone up there commented about the Starship Troopers movie being their only other Heinlein experience. It was *nothing* like the book. Should have had a different title. None of the interesting tech was included and the political talk (which I found interesting since I don’t have to agree with everything I read) was removed as well.

The early chapters are a great read, and I’m inclined to think Heinlein liked that Mike-the-alien well enough to revisit him far more successfully as Mike-the-computer in The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress. Aside from that, the only bit I continue to like is the reading machine Jill uses at Jubal’s house.

My memory of the late 60s and early 70s is that there were the suburbs, still frozen in the mid-50s, and there were universities-and-cities, where plenty of self-proclaimed gurus mixed sex with religion and transgressive-in-a-positive-way came with a large side helping of ick. Hard to know whether too many people had read Stranger in a Strange Land or whether it just nailed the zeitgeist, but it’s a book of its era and it hasn’t worn well, thank goodness. (I read the book in high school in the 60s. It seemed like I should find it excitingly transgressive, but the female characters felt all wrong.) Second wave feminism didn’t arrive a day too early.

I think a 1974 pop song by Paul Anka may (unfortunately) address the “eveybody having babies” motif. The song starts:

“Having my baby,

what a lovely way of saying how much you love me.”

That’s right. Woman getting pregnant = ego boo for the guy. Did I say second wave feminism didn’t come a day too soon?

I still love it, warts and all. I read it when I was 14 – and for a 14 year old guilty Catholic kid growing up in the 1970s it was a tonic. (Please note, I tried to read it a few times while devouring Heinlein Juvies, but never got to the magic moment when Sam Berquist is made to disappear. Once I did I devoured it in a couple of days.)

I saw the same issues, even as a lad, but I accepted the characters spunky smugness as a “sharp” confidence – and equated their style of speech with the snappy dialogue of a 1940s classic movie (imagine SIASL directed by Capra.) And half the fun was being forced to look at the definitions of jealousy and sin and love and death though the eyes of this at times preachy dues ex machina fariy tale.

And let’s not forget, the hero IS Jubal: I sure as hell never wanted to be Mike. (I don’t have hot and cold running secretaries, and my daughters BOTH still remember my birthdays – but I’ve been fortunate enough to arrange a Jubal like existence for myself otherwise.)

Somehow, this is the one Heinlein book I never read. Maybe because it was too popular?

Now, it is even less likely.

joelfinkle @12-

Agree about Number of the Beast, and add Friday– mystery and action both were left behind in “ahhh, it doesn’t matter” endings. Bleh.

After reading the Heinlein biography, and of course Jo’s series of posts, I have been re-reading Heinlein, but I haven’t felt impelled to pick up Stranger again.

Those here put off Heinlein by this should start elsewhere – I am a huge fan of —We Also Walk Dogs myself, but Jo’s suggestions there, and the many voices arguing for The Moon is a Harsh Mistress are worth heeding too.

Re your: ”

My husband, seeing me reading this at the breakfast table, asked if I was continuing my theme of religious SF. I said I was continuing my theme of Hugo-winning SF—but that comes to the same thing. Hugo voters definitely did give Hugos to a lot of religious SF in the early sixties. I hadn’t noticed this, but it’s inarguable. Does anybody have any theories as to why?”

I don’t have a theory, but perhaps this is another symptom of the religious exploration that was prolific at the time. This was (one of) the times of the expansion of religious conscience, with Buddhism, Taoism, and you could even say Shaklee and Amway, with their cultism, coming into popularity.

I read this just after “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress”, and given how famous this one was (and how many peope had suggested it to me before) I expected a lot. I was pretty disappointed, more so since I really really liked Moon. It just….didn’t seem to go anywhere after a point. I came away with the impression of a good story that had lost its way somewhere in the middle.

~lakesidey

Johntheirishmongol: I don’t know how I could have said more clearly that I appreciate this book and the problems are of its time. I said so several times in so many words, so chiding me for that as if it’s something I’d never noticed and I acted as if the book were written now is kind of irritating.

And I don’t think the smugness and the lack of plot were especially popular in 1961. The other Hugo nominees aren’t smug, for instance.

I’ve been reading SSL since I was in my early 20s (the early 80s), and I’ve always liked the book. Unabashedly so. I regularly re-read it once every few years. Yes, it is preachy (smug), but so what? Virtually all of Heinlein’s work is preachy in one way or another.

One of the things I find of interest in the book is the compare-and-contrast between the different religions presented in the novel. nlowery71 mentions the novel presaging Nancy Reagan (so true), but the F0sterites also presage the megachurch phenomenon. Not surprisingly, as I am a Muslim, what I find most interesting is Heinlein’s discussion about Islam. It is the obvious comparison against the Fosterites, and yet Heinlein’s presentation of Islam is about 50% correct-50% wrong. (Some year I keep saying I’ll write a blog post about the Islam of SSL, but I haven’t done that just yet.)

This is the only Heinlein book I have never been able to finish reading. Now I understand why.

Coming at this Heinlein discussion right after a Starship Trooper debate, inevitably framed by that. Compared with that novel, this Hugo winning work certainly seems devoted to different political models, trying to challenge society in ways that anticipated and influenced the hippie movement. Politically speaking I think Stranger in a Strange Land’s heart is a in much better place than the rather vindictive right-wing militarism of Starship Troopers…

…Yet in the end it doesn’t matter, because this book is so atrociously written. Endless authorial rants and speechifying is bad regardless of whether I accept the political account, and the argument that Heinlein gives here are almost as overblown. I’d agree with most of the points of Jo Walton’s review. It’s a shame, the book did start well, with a pretty fascinating premise, and even a lot of the initial intrigue with the world government as pretty good. The problem comes after that when the book develops its main themes, gives Mike magic powers as a way of pushing through all challenges, and starts delivering rather underwhelming final conclusions. “Smug” is a pretty good way to characterize it generally, with the mere fact that these are Heinlein Individuals making them fully justified in all their conclusions.

On the sexism, yeah. My main differing point would be that I don’t see a distinguishing point between Heinlein of this book and all the others. The statements and implicit claims in ‘Stranger’ are not transcendentally worse than the Beyond This Horizon’s instance of a murder attempt by a man towards a women followed by their happily ever after marriage. Or The Door Into Summer’s effective engagement made between the 30 something man and the 12 year old girl, with the later of course waiting years for him and devoting her whole life towards planning to become his wife. Or in Friday, the titular character having a happily ever after marriage with one of the men who gang raped her. Heinlein was a disgusting human being.

All this talk of what conditions were like in the early 1960s and no mention of Mad Men? For shame.

johntheirishmongel, #21:

All books need to be taken in context of when they were written. It’s silly to expect modern sensibilities on a book written 50 years ago. Do we read Dumas or Shakespeare and expect anything like society today? Society has changed more in the past 100 years than it has in human history. And that change is accelerating. So to carp on the lack of feminism or sexual morays is not a fair judgement. It was a book that helped to change society.

The main tendency in literary studies isn’t just to give classic authors a pass, incidentally. We don’t necessarily condemn them for it, but we do try to be aware of sexism and other bias, and not have people replicate it. The second problem is that Heinlein’s attitude here is even worse than many contemporaries; I’ll never claim that Clarke and Asimov don’t write some very problematic things but nothing on the level of what’s on display in ‘Stranger’. Third there’s the problem that this isn’t Dumas or Shakespeare. Among other things this is a didactic work, it expresses its themes not through a complex dramatic rendition but through the characters shouting them. It’s entirely unsubtle and thoroughly preachy, and on that regard looking at the components of what’s being presented as the grand ideal makes sense. And, seeing that it is effectively a creepy male fantasy, is it unreasonable to have that undermine our reading pleasure in that story.

J. Dauro, #23:

Seeing the Starship Troopers movie as an indictment of fascism derived from the text seems to have been the initial point of reference. I’d say the movie is quite good at depicting how the kind of system rooted in Starship Trooper ideals would actually function if implemented: a xenophobic, ineffective military dictatorship.

Jo – wonderful, wonderful write up. I’m with you – the beginning of Stranger is brilliant, and then things go in a different, not as interesting direction. Although I still use the word Grok from time to time, it’s fun to see who knows what it means.

EliBishon said:

“Jo, your comments on the gender assumptions, the unrealistic non-pickiness, and especially the baby-making, made me think of Silverberg’s The World Inside.”

I had the same thought when reading The World Inside, which I read fairly recently, and was utterly creeped out by.

uughh, I just had the worst revelation ever. The first time I read Stranger in a Strange Land i was about 16, and still a virgin. I’ll admit by the time I got to the end I had a little crush on Michael Valentine Smith. a little while later I discovered boys and sex. and boy did I feel like a prude! Unlike my first sexual partner, I didn’t want to have sex with everyone, all the time. Michael Valentine Smith would never like me now!!! How’s that for a totally screwed up sexual hang up??

Agreed that The Heretic suffered from being written in stages by what I’d suggest amounts to a different author

(the past is another country……. frex as I recall someplace in the earliest written tales of the Long family there is a reference to condom use along the lines of pity the poor people who shower in a rain coat much to be deprecated and in one of the last Woody’s grandfather as MD/authority figure is all for condom use – though it make me an idiot I attribute this to a change in authorial attitude and message)

– that is I suspect The Heretic was not rewritten/revised to fit each time nor even back up three steps on restart for mission critical hardware but put down and picked up – and so is very much disjointed. Contrast that with much of Heinlein’s writings which were written quickly from beginning to end and polished once, edited for publishing and that’s the end of it. Frex Glory Road where the internal jumps are equally great but work well.

I credit Mr. Heinlein’s assertion that no one had successfully picked the actual joins – still disjointed. Whether written in the same year or not even the same decade the parts don’t fit however smooth the actual joins. After the model for reading Three Men in a Boat from Have Space Suit…. I can pick up Stranger…. and read a while then put it down later to pick it up again and let it open haphazardly, perhaps to read to perhaps to try another spot.

Of course quack nostrums would never be advertised on TV*

*These statements have not been evaluated by the FDA.

Jo has pinpointed almost the exact point where Heinlein put the book down and stopped working on it for some time. When he picked it up again, a good while later, was with the introduction of Jubal, and yes, the last half of the book doesn’t match the first half aesthetically. It’s too bad he didn’t keep writing, because the book suggested by the first half would have been quite different, and probably better. Jubal was like a black hole, though. Once you introduce him, the pull of his gravity distorts everything else that follows.

It’s similar to HUCKLEBERRY FINN, where Twain wrote the first half of the book and then put it down after the death of his son, not to start working on it again for several years. When he started again, he immediately inserted Tom Sawyer into the plot, and Tom distorted everything that followed much the same as Jubal did in STRANGER. If Twain had been able to finish the book suggested by the first half, it would have been a better novel.

It’s hard to reread now, but in its day, STRANGER broke a lot of new ground and challenged a lot of social assumptions that had been unchallengeable in SF up until then. Unfortunately, its day is long past.

I first read Stranger… when I was eighteen, in my first year of college, in 1974.

My feelings for the book were, then, very tied to the zeitgeist and the fact it had been leant to me by a guy I had a huge crush on, but even so, while I loved the first two thirds, I really disliked the last third.

I re-read it a number of years later and that had dropped to loving the first third and disliking the rest, for many of the reasons stated by others. I’ve always thought Stranger… was the start of Heinlein’s brain-eater period.

That being said, it did inspire me to read a lot of his other books and then to try other SF writers and to go on reading SF for the next 35+ years, so I have a soft spot for it as my gateway drug (along with Zelazny’s Lord of Light, which I borrowed at the same time).

And I, too, still use the word grok every so often.

I’m one of those who has read Stranger in a Strange Land and never touched another Heinlein. I first read it in the early Eighties because I had always heard that it’s a “science fiction classic” and felt I should read it. That time was the winding-down of the sexual revolution. AIDS had struck and we twenty-somethings who had been raised in an era of sexual freedom suddenly faced the fact that promiscuity has a cost. The decade was also the height of the New Age Movement with it’s smorgasbord style of spirituality that was ultimately empty. I completely loathed the book because of that perspective.

While I normally never re-read, a GoodReads group I belong to chose Stranger in a Strange Land as it’s group read one month last year, so I decided to give it another chance. It was on the re-read that I realized that the first part of the book is actually quite good and I was able to express what I hated so much about it. Jo, your review perfectly expresses my opinion about this so-called classic.

Jo,

Thank you, thank you thank you. You hit it spot on.

I completely agree with you – I grew up on the earlier stuff, like Have Spaceship Will Travel, The Rolling Stones, and Farmer in the Sky, but I don’t like his later books at all.

“—and women do indeed like sex, Heinlein was right, but in reality, unlike in this book… we are picky.”

You have put your finger precisely on the problem I’ve had with Heinlein’s attitude toward free love and female sexuality as portrayed in Stranger. And I’ve met too many readers of Heinlein who seem to think it’s the woman’s fault for having preferences of her own rather than conforming to that fantasy.

Hmm. I may be one of the few aboriginal SSL readers. I actually read it in the Sixties. I even had a paisley shirt and bell-bottoms. The tone of the book was exactly in line with the tone of the era, including the smugness that those who were questioning the Establishment were simply and obviously correct in all things and traditional ways were simply and obviously wrong. We still see a lot of that even today.

Heinlein and his wife were into wife-swapping and nudism, as I recollect. He had been an early devotee of H.G.Wells and Bertrand Russell and their ideas of free love. He conceived the novel as a deliberate attack on religion and morality.

One of the things about the free love movements up until that time: They all assumed that if men and women were equal they would be equivalent. Women would behave sexually and in the workplace just as men did, since it was only repression by the Establishment that caused women protect their virginity or restrict the numbers of their partners or insist on a public commitment before engaging in sex.

Sex, political wisdom, or is it the unknowing?

To make bold statements about Stranger in a Strange Land that just come to us because we don’t like how the author writes; portrays a certain sex or how religion is so widly brought up into science fiction creates a separation between what you as the reader thinks is right, due to being raised with morals and values.

Heinlien opptimisticly twisted what was in front of him– “Reality” to a different perspective like many authors do who write science fiction and why many people write in a whole, ex… Stephen R. Donaldson, George Orwell, Phillip Jose Farmer represent a section of writing I like to call “Symbolic Reference” writing.

Casting together different high points and many low points that apparently caused Heinlien to write. Makes me beleive that he created his characters in what he saw in the world. That may not be modern day times but the passed often repeats itself like Global Warming. Heinlien may have created his characters on a “Smug” attitude but can we be as shallow as to let a little muddy water hide the buried treasure. No, we can’t, we have to go deeper. Even if their were low parts in his writing and some controversial subjects to women equality, homosexual acts, and just the whole political system

Robert A. Heinlien shoves in front of us a picture of what he thought was the “truth” in a nut shell. Through his writing, thoughts, and emotions to certain topics gives us more of his voice then more realize to be there. Captivating millions and a million more who diagree with his writing brings us back to the old saying “Beggers can’t be choosers” but the beggers can say no.

I still love this book (and unlike many others I like the uncut version even more; it has looser, more comfortable pacing–although the opening sentences are better in the cut version).

I agree with Jo and everyone else’s analysis of the book’s flaws; they are legion. I simply don’t care. The thing about Stranger (like the rest of Heinlein’s best work) is that it asks really interesting questions. The fact that I disagree with most of Heinlein’s answers doesn’t detract from the enjoyment I get from reading the story and thinking about my own.

I was already a Heinlein fan when Stranger in a Strange Land came out (I was 14). As Jo says, parts of it were wonderful. But it was overblown (it must have been pretty well the longest sf novel ever published up to that point) and at times just plain dull. And Jubal (who recurs under different names in all subsequent Heinlein novels) was insufferable. But I do find it very sad that there are people on this list who read this novel and hated it so much that they never tried another Heinlein. Read the juveniles from the late forties and fifties! Indeed, read any Heinlein published before Starship Troopers.

Maybe we just lack the drugs necessary to make the “great leap” of understanding?

“Smug Messiah” — that nails it.

Excellent.

@54: No, you have to be a Martian.

Yep, that’s the point where the book turned quite dull for me also. I had pretty much the same experience as Jo. I recall reading along and enjoying the book right ip to that point. And then it change–not for the better as Jo mentions.

That’s interesting that that was where Heinlein put the book away for awhile. It had always felt like that to me, but I hadn’t seen a confirmation.

When Stranger in a Strange Land was so very trendy, I used to suggest, “There’s this other great book he wrote at exactly the same time. Why don’t you check out Starship Troopers?” Several years later when Fear No Evil was so trendy with the sexual transgressives (talk about smug!), I was able to make the same recommendation, almost verbatim.

Hey guys im new to this web site but i have enjoyed many of the books Tor has published. i was wonering if there was a way to put your writing on the site. I guess like blogging?

Any help would be great, thank you guys.

Disclaimers: Age 53, reading Heinlein since age 8 or so. Read all his work, as far as I can tell.

My favorites: Moon, Glory Road.

My least favorites: SSl and everything after. The obsession with the wise old man whose goal in life is to prove to the younger generation that they did not invent sex. The smugness. The cheap outs especially in the later books. God the fail of attempting to tie all his books together [Asimov did a much better job].

I agree with the comments above; I thought this book was over-rated

I loved, loved, loved Stranger in a Strange Land as a kid — I think I was probably about 11 when I read it. I would have listed it as my favourite book probably well into my twenties (I’m 40 now). For several years I used to reread it every year, then I went to every two, and now it’s probably been six or eight years since I read it.

I totally believed it as a kid, plus it offered the promise of cool superpowers if you could just learn to speak Martian, what’s not to like? In later years I did feel some of the smugness, plus I think I just got bored of reading it over again. There are still several fun scenes, and I do enjoy the language, but I don’t plan on reading it again anytime soon. (I hope they make a movie version, though. Maybe the guy who did Starship Troopers could do it.)

Susan Loyal “large side helping ick” MADE MY DAY may I USE that?

Heinlein was one of the really obvious early examples of what’s come to be called “the brain eater”. The symptoms include suddenly, late in a successful literary career, starting to tie all your universes together. It’s a tragic affliction.

And Stranger is where it became really apparent in Heinlein. All the seeds for the extended going down-hill for the rest of his career are quite clear right in this book.

As Jo says, they’re Heinlein sentence, it’s still compulsively readable. But it’s not nearly as interesting as his better work (including some that came later; I would say that The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is his best work, and serialization of that started in 1965).

There’s a theory going around, that I don’t have a source for, that Heinlein deliberately set out to challenge all the assumptions of society. If so, it’s a shame he couldn’t get past his issues with homosexuality. His books show an interesting progression; here, Mike would sense “a wrongness”. In Moon it’s what men who can’t find women may resort to. But by I Will Fear No Evil there’s a pair of gay lawyers who are minor good guys, and their sex life isn’t germane. And in Time Enough for Love Galahad and Ishtar agree to “seven hours of ecstasy” without knowing each others sex (he then spoils the effect by having them glad to turn out to be male and female; then again, that implies they pretty much expected it to be a homosexual encounter, and still agreed to it).

Heinlein was clearly something of a mystic. This is one of the areas where I just don’t get along with him very well (despite his being pretty clearly my favorite author).

I haven’t quite seen anybody put it this way; or a way that I find strong enough. In the end, what’s wrong with this novel is that it’s a cheat. Things work because of martian magic and the insights of the martian language — and those don’t exist, so we don’t have access to them.

dd-b @63: The progression doesn’t really stop with Time Enough for Love. In Job, the main character finds himself getting aroused by the butt of what he believes to be a (male) bellboy at one point. There’s a bit of ambiguous banter and the bellboy is revealed to be female. Then in The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, Colin Campbell wakes up to find himself in bed with a man (might even be Galahad, IIRC). He freaks slightly, then remembers an incident with a scoutmaster and decides to just let it be.

In one of the discussions on the biography back in October, there was some suggestion that he might have had an experience or two when he was in NYC. If so, he may have had some things he needed to work his way through. (OK, 50 years is a long time, but he also had to be aware of those issues, too.) OTOH, the evolution you see may simply reflect how far he thought he could push the envelope at any given time.

Heinlein was progressive and a revolutionary, he

was just unlucky enough to pick progressive, revolutionary causes that weren’t only parochial, but later turned out to be just as annoyingly reactionary as the majority of other revolutionary ideals.

He tried to explode sex, and railed against the restrictions that society puts on the act. While in a perfect world any person should be free to join, at whatever age, in consensual sexual relations, he never admitted to himself that we’ll never live in a perfect world. A minor is almost never going to be able to engage in consensual sex with an adult, because they’re simply to inexperienced to be able to say ‘no’, and polyamory, while great for consenting equals, is a disaster for those who through peer pressure and the dominance of strong religious/social figures are forced into relationships.

His later views on economics are only a shade less insane than Ayn Rand. While people shouldn’t be forced in collectivisation by any stretch of the imagination. Like Ayn Rand, he tends to forget that taxes pay for education/roads/health care/police etc. that end up allowing an individual to gain wealth by employing people who have a good education/can travel to work/aren’t dying of consumption.

He’s a great, no doubt about it, like you say, he never wrote a bad line. I wish I lived in a world where we could live as he obviously wished we could, but we can’t and his tragedy is that he couldn’t see that.

I’m reading this book – the uncut version – for the first time, having managed to avoid it during my hippie years.

I agree with most of what Jo says about it, particularly the smugness.

Some aspects of the novel remind me of another “aliens transform the world” novel that I did read in my youth: Asimov’s “Childhood’s End”. I recently re-read that, and consider it a much better work than “Stranger in a Strange Land”.

David Sharp (Paris)

Oh, dear — this discussion is long dead, and yet I can’t help joining in.

I just reread “Stranger” for the first time since reading it as a teen in the mid-seventies. I pretty much agree with all Jo’s criticisms. And yet I still love the book.

I remember, even as a teen, finding the whole Playboy mansion vibe pretty disturbing, and feeling that Jubal was a wealthy bully, albeit a well-intentioned and interesting one. On the other hand, I don’t think Jubal is written as always being correct; in one or two places, he confidently states opinions which the narrative demonstrates to be wrong — Heinlein was smart enough to give himself an out. I think the idea that a religion which is initially presented satirically can eventually become a vehicle for true spiritual transformation is still brilliantly subversive and disturbing. And the pre-messianic Mike is, IMO, one of the best Holy Fool characters ever written. As another commenter here pointed out, the book asks such interesting questions that I can forgive some of its really dumb answers.

Virginia @@@@@ 68:

What I like best about the book now is that Mike’s Martian religion and the Fosterite religion are exactly the same: Well-marketed religions with an orgiastic inner cult, with miracles that work (by whatever means necessary), and with actual delivery to heaven.

I stopped reading the book a while back. I have been thinking that there is something terribly wrong with me. How could I give up on something that captured the imagination of millions of people? I couldn’t figure out the reason why i didn’t want to move further. But after reading this article, I am pretty sure.

But I’ll pick it up again.

It was a novel of it’s time, and I think now it seems sexist and probably “smug” is a good description. I read the first half of it when I was 11, in 1961 or ’62. My parents discovered it and made me take it back to the library unfinished. However, I was already corrupted! I realized that beyond the tightly strapped down ’50’s, and early ’60’s there was a whole huge world of possibilities in behavior and existence! Our view of life was so very narrow then! I finally finished the book in the later 60’s and found the last half kind of a bore.

I just finished the book and I’m glad I’m not the only one who is very disappointed. It starts great but it goes downhill fast. I really like The Moon is a Harsh Mistress and Starship Troopers though. I was expecting Stranger to be just as great but it’s a complete disappointment for all the reasons discussed here.

I’ve just finished this book, which I read at my husband’s urging (I’d avoided it until now; and now I know why), and I could have written your review here myself — it echoes everything I’ve been hating about it. One recommendation I can make which improved it greatly, and worked until all the “Yay babies” stuff came in at the end, was making Jubal an old drag queen surrounded by hot young dudes (and gender-switching a few other characters, too, as necessary, although I left Mike male and pansexual). But overall, what a disappointment, especially all the long-winded conversations about the wonderful new religion as one reaches the point where it seems like something urgent and climactic ought to start happening. Maybe Heinlein thought burning the church building and killing Mike was exciting, but I was just dying of boredom and begging for the book to be over by the time I got there. And I had such high hopes for it.

Great review! My partner has tried to get me to read this book for about a decade; 3-4 times I’d get to Jubal and his 3 secretaries and give up. This time around I got a lot farther – Jill’s comment about 9 out of 10 women are asking for rape was my final line, I’m not going to bother to finish the novel.

It’s a shame, I absolutely adore “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress” and I enjoyed “Job” too, but this book was too much. You got it spot on with all the female characters being the same damn young beautiful woman. I thought the beginning of the book holds so much more promise than the unfortunate story it winds out becoming. I got a huge kick out of the “malthusian lozenges” concept, but this book really went in a direction I cannot handle.

Thanks for a great review! It can be difficult to find a woman’s point of view on on different topics, and you really summed up a lot of my contentions with the novel so eloquently!

You know what? I liked the book when I read it in ’71 when I read it at the age of 12 and I positively adored it when I read it again at the age of 15. I read it and reread it and reread it. Probably by my late 20s, I’d stopped thinking of it as “The Book of Truth,” but something I have always liked about Robert Heinlein’s books from the first one I picked up at the age of 10 until now is that he made me think. He made me look at the world in a different way. He made me question authority. I like that. I don’t see the smugness the rest of you see. Are there some bits that bug me? Sure. But to slam him on “9 times out of 10 if a girl gets raped it’s her fault” (which made me cringe then and now) and that Mike would “grok a wrongness in the poor in-betweeners” considering when the book was written and published is as ludicrious as my grandfather asserting that Shakespeare was an anti-Semite because of the Sherlock character in Merchant of Venice.

I’ve read every word that Robert Heinlein has published, some I liked more than others, some would benefit from some judicial editing, but all amused me and made me think, and that’s more than I can say for a lot of writers I’ve read.

Well, I just finished the uncut, 525-page version of Stranger In A Strange Land.

…what a horrible reading experience that was. Agonizingly slow, preachy and plotless. 80% of the book is just characters talking at each other about how the world works. And yes, I also found the sexual attitudes problematic. It’s not the nonmonogamy in itself. As Jo said, it’s the expectation that all the women will be willing to share themselves with all the men in Mike’s church. It makes the church seem less like a community of enlightened superhumans and more like a creepy sex cult.

Prior to this, I’d read six other books by Heinlein and liked *all* of them. I’m glad I didn’t start with this book, otherwise I might not have read anything else by him. I’m sure that I would have preferred the edited version of Stranger In A Strange Land but it now seems unlikely that I’ll touch any version it ever again.

PLEASE don’t judge Heinlein by one book, and especially don’t judge him by that horrible mess of a movie that they stuck the name “Starship Troopers” on. Thanks to that waste of celluloid, the Heinlein family has refused to sell film rights to any of the other books.

Les Caudill @79,

I totally agree that the film version of “Starship Troopers” was garbage. The movie version of “The Puppet Masters” that came out a few years before (released in 1994 vs 1997 for ST) was pretty good. The film makers achieved this by adapting the rarest of Hollywood strategies: actually sticking to the book.

I found “The Puppet Masters” a passable film compared to the source book. The ST film owed almost everything except character names and a few sociatal concepts to the simalar novel “Armour” by John Steakley. And that being said Sometimes you just gotta remember rule 62. Ya know, sometimes it’s just a movie. If you need to be heavily informed and engaged in deep thoughts, Community College. I do however love to watch the reactions of my less intellectual cohorts when I tell them that sci-fi is an examination of the human condition. Sometimes prophetically.

First off, the hack author LRHubbard redirected his fledgeling Scientology as a Fosterite spin-off of the Church-of-All-Worlds. Second, some of Heinlein’s most formative transformation as a sexually-reassessing, SF author occurred while he was a resident of Laurel Canyon of Hollywood Hills, CA fame.

You should check out “Weird Scenes Inside the Canyon” by Dave McGowan, he gives an interesting perspective of the beginnings of the Hippie culture.

DanD

The gay thing ruined the book for me, forget anything else. Do you know if his ideas ever evolved regarding that?

Sorry to wander into this discussion so late. I can see the point of the person above who urged people to read any Heinlein before Starship Troopers. I was lucky enough to discover Heinlein through the collection The Past Through Tomorrow, a collection of his “Future History” stories from the forties and fifties, and then went onto his “juveniles,” etc. I might well stick to his works of this period and avoid Starship Troopers, Stranger in a Strange Land, etc.

I think it was the SF critic John Clute who wrote that Starship Troopers was for better or worse the beginning of Heinlein Unbound. Maybe he was better when he had some editorial restraint.

I just read Jo Walton’s article and comments, and am disappointed. Stranger was groundbreaking in 1961 and remains so in 2017. The book shakes down pieties, satirizes stupidity, and explores alien thinking better than any science fiction book before it (that I’m aware of). The statements about Jubal Harshaw’s presence ruining the book in the second half are bizarre. He enters a book with 39 chapters in chapter 10. Walton’s welcome to like what she wishes, but I hope for her sake another author doesn’t tell her readers not to read Walton’s books (like she did on this one).

Jubal was my favorite part of the novel. Guess that makes me the odd woman out.

I just came across this review by accident, and I reckon it does a good job of identifying the good and bad bits of the book.

I was born in 1954; I used to like and reread this book and some other Heinleins. By now I think Heinlein’s works haven’t lasted well in general, and I don’t normally think of looking back at them. However, I’m still glad to have read and reread this one, because it does have some good bits, and a number of images that stick in my mind. Today I was thinking about something completely unrelated, and I was reminded of the Martian artist mentioned briefly on one page, who discorporated without noticing and went on composing his artwork.

I’m not sure, though, that I could feel justified in recommending the book to a youngster today. There are so many more modern books competing for attention. And, indeed, a number of quite old books that have kept better.

Its funny that my experience of the book is the exact opposite of the reviewer’s. For me the book does not get going till Jill rock’s up at Jubal’s house. Up until then it is all just exposition. I think the book would have been improved if it just started at that point. Until then the characters are all just tired cookie cuts. Even Mike is just a semi alien with a built in ray gun. I was relieved to see Ben Caxton well worn character leave the story.

The ending of the book is I feel the reason the book has endured so well. It brutally challenges our presumptions about power and the justification for using it even if reader do not immediately appreciate it they are aware they are being shown a very big idea. Throughout the book Mike gains more and more power, political, physical, sexual, personal, economic. By the end of the book, he has the power to overturn governments and break planets. Then when is power is at its highest and he is in a position to smash his enemies he turns aside from the use of power – even his own bloodless kind. He uses his enemies violence against them, their own use of violence martyrs him and his movement unstoppable, He changes the argument so it is no longer about who has the most power to back up their position.

That is what is so great about Heinlein he is always leading you down one path and just when you are feeling smug and comfortable he switches direction and lays bare your own presumptions. Its funny that the reviewer highlights the smug nature of the characters: Heinlein is constantly gently parading that smugness.

Heinlein’s home in the SantaCruz Mountains (Bonny Doone) looks like how I would expect Jubal’s home in the Pocanos to look.

@@@@@ 63, dd-b

There’s a theory going around, that I don’t have a source for, that Heinlein deliberately set out to challenge all the assumptions of society.

I read it when it was newly out, in hardcover. The stuff about Heinlein challenging all the assumptions of society was in a blurb—or perhaps an introduction—to that edition.

I just hate I have wasted so much time reading Stranger. Thanks for a terrific writeup – now I know I’m not just crazy!

It is April 5th,2020. I sit sequestered in my apartment in Ohio. Outside, the Covid-19 virus ravages the world. The threat of a premature death hangs in the air. And though my time has become more important to me than ever, I still felt compelled to sacrifice some of my valuable time to read this entire thread and register with the Tor website, with the hope that I can warn all future generations that Stranger in a Strange land is, in fact, the worst example of Sci-fi writing I have ever read. The book had come highly recommend from a friend of mine who was, albeit, a child of the ‘60’s counter culture, but whom I considered erudite. I can understand how the anti establishment concepts presented in the book were galvanizing at the time; but, what readers of English could ignore the sloppy and slipshod construction of the overall narrative of the novel? Great ideas alone do not make an award winning novel. It’s all in the execution. Right? The only way this book works is if Heinlein intentionally wrote it as a satire not of contemporary culture, but a satire of bad science fiction writing in general.

Aw shucks Jo,

Ya done ruined it for me! Which is just as well, I was gonna read the uncut version, but I really haven’t got the time, what with all the TV show I still have to binge watch, from the timetravel Japanese anime Steins Gate till the small and sweet Better Things to the Big Box modern classics The Tudors, and La Casa de Papel, etc etc.

I must say, I kind of agree with your general take on the book, but I’ve got some minor points. Yes, the baby stuff is an example of writing what you yearn for. He was childless, with either wife, so its must’ve been him. This why he lionizes the military stuff so much, he’s a failed soldier, and a failed politician which is, I guess a major motivation for “Doublestar“.

In a lot of his later books, “To sail beyond the sunset”, “The cat who walks through walls”, large families have a significant role, SiaSL is no different, and may be what started it all. Also, we shouldn’t forget that it is a, admittedly somewhat juvenile, reaction to the criticism of Starship Troopers, which many described as fascist . One can argue that Heinlein must have thought something along the lines of: “What? Me fascist? Well, I’ll show ya!” and then wrote SiaSL which is (despite the smugness) seen as a lovey-dovey hippy flower power book. The only pity is perhaps that it also inspired Charles Manson to model his “Manson family” after Michaeals family.

What irritated me about Heinlein started with the Notebooks of Lazarus Long, Unlike Asimov and Clarke, Heinlein has a persistent anti-government streak, which for me as a European teen, was quite bizarre. Then again, I’ve also read Orson Scott Card and he’s waaaaaay worse than Heinlein, an out and out rightwing extremist homophobe, who preached that using violence against Obama would be legitimate action, because … health care. After that, I’ve stopped reading Card, also because he pushed this opinion online on his website, but he didn’t have the guts to do it in his work where he rather cowardly maintains a liberal image.

But Heinlein… I can read him again and again in small doses. It’s certainly not literary, his characters lack development, and books like Number of the Beast are way too Disneyfied in their endings. Also, the ultimate smugness of Heinlein for me is that he thinks he can write women. I mean, I’m a man, and even I can see that his women aren’t really real women, but men with a vagina who are, like you said, always willing and able to service men. I’m both happy and ashamed that Heinleins homophobe stuff and Jill’s rape victim blaming attitude completely escaped my attention. I don’t really know what else to say about that. RAH is a good writer, in his field but will his stuff last throughout the ages? Hmmmm, dunno. I guess as long as the Old White Male perspective will dominate the world (and I guess this could last a LOOONG time, given the strangle hold Trumpublicans hold on America, the US army and thus, the world) Heinleins Dead White Male’s attitudes could still sell a lot of books. There are more and more rightwing Scifi writers these days, which is worrisome.

Thanks for your smug-messiah take, it was helpful and enlightening about Heinlein.

Thank goodness I have heroic levels of self-control or I would poindextrously correct you with “all _three_ wives.”

@94 thank goodness for that, yes …..