Sooner or later I’m going to write about all the juveniles—you can just resign yourselves to it. Red Planet (1949) is not the best of them, but it’s not the worst either. I first read it when I was reading all of SF in alphabetical order when I was thirteen, a process I recommend. By the time you get to Zelazny you will know what you like. I liked Red Planet, and I’ve re-read it about once a decade since, but it has never been one of my favourites. I re-read it now because I was thinking about child markers and I couldn’t remember it well enough to see how it did on that.

The reason it isn’t a favourite is because Jim, the hero, is very generic. He’s a standard Heinlein boy-hero, with nothing to make him stand out from the pack. The most interesting character here is Willis, a Martian, and even Willis isn’t really much of a character. And the plot—a revolution on Mars—is oddly paced and doesn’t entirely work. So I suppose it is really a book with rushed plot and a bland hero. What makes it worth reading then?

Well, obviously, the setting.

Heinlein has really thought about the Mars he gives us here, and I’m sure he used the best science available in 1947. It’s regrettably obsolete now, but that doesn’t make it any less interesting to read about.

We have here a Mars with canals, with flora and fauna adapted to the thin air and extreme temperatures. The canals freeze and thaw on a seasonal rhythm. The human settlements are either equatorial, or migrate from north to south to avoid the winter. People wear suits with air filters when out of doors—and with a lovely Heinlein touch, they paint the suits for individual recognition, and making them stop this is one of the first signs of repression. And we also have intelligent Martians—I think Heinlein has intelligent Martians in every book he possibly can. (And really, who can blame him? Intelligent Martians are about the niftiest thing ever, and I was very reluctant to give up on the possibility myself.) The Martians here are especially cool, with a young form that resembles a bowling ball with retractable legs which Jim adopts as a pet, and with an “old one” form that is actually a ghost. Interestingly enough, this could well be the same Mars as in Stranger In A Strange Land (post). As well as the “old ones” there are water-sharing rituals, Martians making people disappear into non-existence, and several instances of solving problems with Martians ex machina.

Jim and Willis are genuinely attached to each other, and Jim’s refusal to leave Willis behind or accept his confiscation largely drives the plot, attracting the interest of Martians and of the evil headmaster. The attachment is much like that of boys and dogs in classic children’s literature, with the twist of Willis’s developing intelligence. Heinlein did it better in The Star Beast.

The plot has its moments, but it doesn’t really work. Jim is sent away for advanced education at the equator and takes with him his Martian “pet.” This coincides with a move from the company running Mars to become repressive. Jim escapes with his pal Frank, and Willis of course, and makes it home. There’s a terrific bit where the boys skate down a canal and spend the night inside a Martian cabbage. They get help from the Martians and make it home, whereupon Jim’s father leads a revolution. Jim, who never had much personality, fades into the background from them on. Heinlein has clearly thought about the difficulty of revolution in a place where heat and air can not be taken for granted and everyone is utterly dependant on their suits for survival. There’s a shape you expect to a plot like this, and it isn’t what we get. Jim retreats into the background, and the revolution succeeds because of the ordinary people refusing to go along with the idiots in charge once they understand the situation—and the Martians, of course. And was Willis turning out to be a juvenile Martian supposed to be a surprise? It seemed telegraphed from the beginning to me when I was thirteen.

It’s not one of Heinlein’s best, but it’s short, and it has Martians. I’ll keep reading it every ten years or so.

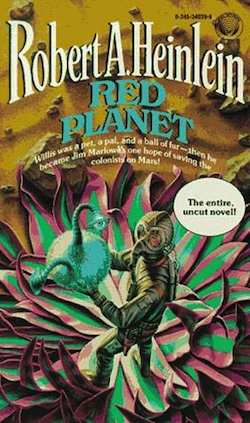

My edition (Pan, 1967) has a horrible cover. It has two figures seen from behind who appear at first glance to be in armour—though on examnation you can tell they’re kind of spacesuits. One of them is firing a tiny gun at a giant monster which has pincers and a huge head that resembles one of those horned cow skulls you see in generic deserts. The worst thing about this cover is that I can, in fact, tell which scene of the book it is intended to illustrate, and yet it does it so badly that it completely misrepresents everything about it. They should have gone with a generic planet and spaceship. But really, if you have a book about a three legged alien and you want people to buy it, for goodness sake put it on the cover!

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.