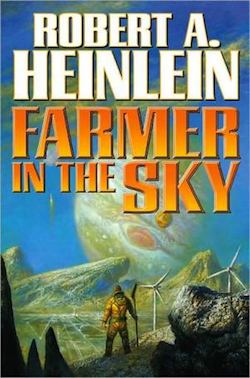

Farmer in the Sky (1950) is about Bill, an American Eagle Scout who goes on a ship called the Mayflower to colonize Ganymede. There’s a lot more to it than that, of course. There’s a long space voyage with scouting and adventures, there’s lots of detail of colonizing and terraforming and making soil, there’s a disaster and the discovery of alien ruins, but it’s all subsidiary to the story of how Bill grows up and decides he belongs on Ganymede. This is one of Heinlein’s core juveniles, and one of the books that shaped the way people wrote a certain kind of SF. I can see the influence of Farmer going very wide indeed, from Greg Bear to John Barnes and Judith Moffett.

Gregory Benford has written some beautiful detailed posts about the science of terraforming Ganymede and his appreciation of this book. I’m going to look at the social science and the people. In fact, I’m mostly going to look at a truly excellent description of making dinner.

This is a particularly dystopic Earth—there’s overpopulation and stringent food rationing and too many regulations. Having said that, they do have flying cars and scouts are allowed to pilot them, so it’s not all bad. They also have space colonies on all the nearby planets and they’re busily terraforming Ganymede. Bill’s mother is dead and he lives with his father, who forgets to eat when Bill isn’t home—it’s clear Bill is caretaking. Then his father announces that he is remarrying a widow with a daughter and the blended family is going to Ganymede. I don’t think there’s any description of how either missing parent died. Now people do die, but when I think of blended families, normally, I think of divorce. One dead parent could be considered an accident, but losing two looks like carelessness some background disaster not being talked about. This is an overcrowded over-regulated Earth anybody would be glad to leave.

Benford mentions that Heinlein predicted the microwaves, except it’s called a quickthaw. I want to take a closer look at this whole fascinating passage, because it’s doing so much in so little space, and predicting microwaves in 1950 is the least of it:

I grabbed two synthosteaks out of the freezer and slapped them in quickthaw, added a big Idaho baked potato for Dad and a smaller one for me, then dug out a package of salad and let it warm naturally.

By the time I had poured boiling water over two soup cubes and coffee powder the steaks were ready for the broiler. I transferred them, letting it cycle on medium rare, and stepped up the gain on the quickthaw so that the spuds would be ready when the steaks were. Then back to the freezer for a couple of icecream cake slices for dessert.

The spuds were ready. I took a quick look at my ration accounts, decided we could afford it and set out a couple of pats of butterine for them. The broiler was ringing. I removed the steaks, set everything out and switched on the candles, just as Anne would have done.

“Come and get it,” I yelled, and turned back to enter the calorie and point score on each item from their wrappers, then shoved the wrappers in the incinerator. That way you never get your accounts fouled up.

Dad sat down as I finished. Elapsed time from scratch, two minutes and twenty seconds—there’s nothing hard about cooking. I don’t see why women make such a fuss about it. No system probably.

Heinlein lived through the thirties, where poor people in the U.S. were genuinely hungry. It was a huge formative experience—Kathleen Norris, a romance writer, developed the idea that food ought to be socialised and free, and it comes up over and over again as a background detail in her fiction. Heinlein remained convinced “we’ll all be getting hungry by and by” until he revised his predictions in Expanded Universe in 1980. But here in this 1950s book, we see a tyranny of food consumption far more stringent than British WWII rationing. Overpopulation was something a lot of people were worried about then too. I find the failure of this prediction cheering.

But it’s also a brilliant piece of writing. Yes, he predicts the microwave, but I’d much rather have that automatic broiler—mine’s identical to a 1950s one. But look how much else is in there. Bill is taking the restrictions and regulations entirely for granted—and Heinlein shows us that by having him pleased to be able to afford “butterine.” Baked potatoes microwave okay, but are massively inferior to oven cooked potatoes—the skins are soft and the texture sucks—but Bill takes them entirely for granted too, along with the “synthosteaks.” He doesn’t lament the texture of the potatoes or miss real meat, he doesn’t know any better. Bill is proud of his cooking ability and has no idea he’s eating food his grandparents would have sneered at—synthosteaks and soup cubes indeed. Bill doesn’t even feel oppressed by the necessary record keeping. But Heinlein very clearly horrifies the reader of 1950 (or the reader of 2011 for that matter) precisely with Bill’s matter of fact attitude to this stuff. Heinlein is correctly predicting an increase in convenience food and kitchen gadgets to save time, but he’s also showing the way people get used to things and think they’re normal. He’s showing us masses about the world from the things Bill takes for granted.

He’s also showing us masses about the characters. He’s telling us Bill’s mother is dead, he’s telling us electric candles are normal, he’s showing us normal family life of Bill cooking a nice sit down meal for the two of them. He’s showing us Bill’s pride and acceptance and that they’re still missing his dead mother. “Just as Anne would have done” is six words which cover an immense amount of ground in Bill’s personality, his relationship with his father since his mother’s death, and the relationship of both of them with the dead Anne. He’s a teenage boy and he’s trying really hard.

Indeed, there’s a huge amount of information in those five little paragraphs about making dinner. This is what Heinlein did so brilliantly. The world, the tech, the rationing and the social structure that implies, and the personal relationships. And it’s all conveyed not only painlessly but breezily and as an aside—Bill thinks he’s telling you how he made dinner that day in two minutes and twenty seconds, not explaining the world, the tech and his family arrangements. Astonishing. You could do a lot worse than read Heinlein to learn incluing—I love the way he weaves information through the text.

The blended family is done well. Bill at first resists the arrangement and then later comes to be comfortable with his stepmother and stepsister and eventual new siblings, in exactly the way teenagers often do react to this kind of thing. But it’s not central. What we have is a story of a boy becoming a pioneer, becoming a man without the usual intervening steps of school or qualifications. There’s enough adventure to satisfy anyone, but it’s really all about Bill growing up.

My favourite thing in this book is the Schwartz’s apple tree. Here we are, barely five years from the end of a war with Germany and there’s Heinlein putting in a German family as significant positive characters. And there’s something about the apple tree, the only tree on Ganymede, and the apples which are treasure because they contain seeds that might grow new trees. The whole thing about proving the claim and all the detail comes down in my memory to this Johnny Appleseed image. You need all the science to support the poetic image, but it’s the poetic image that sticks with me.

I have no idea how Farmer in the Sky would strike me if I read it for the first time now. I’m lucky enough that I read it when I was at the perfect age for it. I wasn’t American or a boy or a scout (and goodness knows there are no interesting female roles in this particular book) but I found the scouting and the American patriotism exotic. I should also admit that I had encountered so little U.S. history when I first read this that I did not recognise the “Mayflower” reference, and in fact encountered the historical Mayflower after Heinlein’s space version. Oh well, it didn’t do me any harm.

It’s a very short book, barely an evening’s reading time. I was sorry to come to the end of it, but I don’t wish it longer—it’s just the perfect length for the story it has to tell.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

But here in this 1950s book, we see a tyranny of food consumption far more stringent than British WWII rationing. Overpopulation was something a lot of people were worried about then too. I find the failure of this prediction cheering.

Good old Norman Borlaug.

The weird thing about Farmer is that it doesn’t have a Borlaug analog; you’d think with that many people and some impressively advanced technology, some brilliant someone would have turned their mind to the production of food. Instead, their solution is to terraform Ganymede….

One nitpicky point — of course he takes the texture of the potatoes as normal. At the time this was written, the “quikthaw” was theoretical and not exactly a microwave — and I think this was pre-microwave, certainly pre-commercially available microwave, so nobody knew the texture would be different. (I *said* it was nitpicky!)

We are not told how his step-mother’s husband died, but I think that Bill and his mother were going somewhere in their ‘helicopter’ and he had gone out to release the tie downs – she took off and hit another passing vehicle. It might have been one of RAH’s other juveniles though.

Percy Spencer discovered that the magnetron he was playing with had melted the chocolate bar in his pocket in 1945 (let’s all think about the other things he could have discovered he had cooked with his unshielded magnetron (1)) but the first commercial radaranges showed up in 1947: they were huge, water-cooled, expensive and drew power like crazy. Home models began appearing in the 1950s but true commercial success was not enjoyed until the 1960s.

1: The second item deliberately cooked in a microwave was a whole egg and yes, hilarity ensued.

One other thing this passage does is set up the contrast with the food on Ganymede colony — which is ‘natural’ (and again, some great incluing: vine fruits but no tree fruits or nuts; no coffee; wheat and salt are rare). This from about halfway through the book:

There are elaborate listings of lunch and dinner too — a young man with an appetite marvelling at real food.

James: my impression is that midcentury Malthusian fatalism would say “maybe they did, but it doesn’t matter”, because population would inevitably increase to offset any increase in food supply. I don’t get the impression that the demographic transition was widely predicted.

Jo: the thing that always throws me re the blended family is the way Bill’s dad blindsides him with the marriage. He’s obviously already serious when he starts to hint about emigration, and is equally obviously deliberately keeping Bill in the dark. (Bill notes that emigrants have to be married couples with kids, dad says “Don’t give it a thought.”) Bill doesn’t even know they’re dating till dad tells him they’re getting married.

I have no idea what was common practice in the 50s for divorced/widowed parents, but that seems almost calculated to maximize Bill’s difficulty in accepting the new situation: “Surprise! You have a new mom and a new sister! Welcome to Ganymede!”

As dystopias go that Earth is not so bad. It’s crowded and there’s rationing, but there’s still enough food and clean water. I am left with the sense that Heinlein though his audience was easily shocked.

6: I don’t get the impression that the demographic transition was widely predicted.

No, Malthusianism was an outgrowth of worries of population stagnation in the advanced economies, and more than a bit of the fear of Yellow Menace/brown hordes. The concept of the demographic transition was formulated in 1929 — two-nine — by Warren Thompson, but Europeans of the interwar period were already fretting about the possibility of population decline (and especially how it might affect their militaries).

A slight tangent. Heinlein’s comments about how horribly crowded Java was in Tramp Royale — a “horizontal slum”, if memory serves — seem pertinent here. The island had a population of about 50 million then. It has a population of about 140 million now. It’s also about four, five times richer per person on average.

Tramp Royale (based on a world tour ca. 1953) is very good at illuminating Heinlein’s views on population and resources around this time. To call them ‘social Darwinist’ might be an understatement.

Not to completely monopolize the discussion, but if you want to know more about the kitchen Heinlein physically designed and built, it’s available in the Google Books’ archive of Popular Mechanics, June 1952.

[do I dare attempt a link?]

The design philosophy is, to my eye, clearly influenced by Heinlein’s naval life.

One dead parent could be considered an accident, but losing two looks like carelessness some background disaster not being talked about.

I think it’s for the same reasons the Brady Bunch had a similar set-up two decades later (1). Polygamy is out if RAH wants to sell this as a YA but using divorce to get rid of the inconvenient spouses probably would be a hard sell for a YA in the 1950s (As much fun as “I’m dumping your mom, marrying this stranger and taking us all to Ganymede” could have been). That leaves only a double-death and even there it probably has to be accidental; divorce-by-murder is right out.

1: Techinically we don’t know how Carol’s marriage ended; it’s never explained. It’s never said to be divorce, though, because the network nixed that.

The Brady Bunch as a post-Cuban Missile Crisis gone hot blended group of survivors could work. Let me think about this….

clearly influenced by Heinlein’s naval life.

See also Bill’s dad’s management style: decisions are dropped on subordinates and it’s the junior officer’s job to make things run smoothly for the senior staff.

Michael@6,

Yes, that decision always bothered me too. I was a divorced kid of the early ’70’s, and I can’t imagine either of my parents hiding a relationship- certainly not one leading to marriage- from me.

James@11,

And what was up with the Bradys anyhow? The dad was an architect- couldn’t they have added some more bedrooms?

My guess would be that they didn’t build an addition because dad was an architect; adding the addition would have ruined the lines of the house for no better reason than to make life a little easier for the people who were lucky enough to live there.

I last read Farmer in the Sky about 20 years ago, so take this with a whole bag of salt, but I thought the implication of the hasty marriage was that it was to some extent a marriage of convenience in order for the merged family to be eligable for emigration to Ganymede.

I don’t mind the crowded Earth– it’s not so bad to have science fiction about difficult but non-crapsack places, and it’s more plausible that a place where civilization is still functioning smoothly is going to be able to terraform Ganymede.

The view of nearby Jupiter is one of the few major visual effects Heinlein wrote– offhand, I can think of the redwood forest in Beyond This Horizon and the painting in I Will Fear No Evil. Any others?

The sensory aspect is interesting for me because there are some writers whose work I have trouble focusing on (Schmitz except for The Witches of Karres, Piper except for Little Fuzzy) and part of the problem feels like not enough sensory input.

In Heinlein’s case, it may be that the voice is so strong it makes up for lack of sensory specifics. Or possibly that he does such a good job of describing how things work that it’s a good substitute.

Karen’s death is interesting because it’s Darwinian, but it’s not asshole Darwinian. She died because she couldn’t survive in a new environment, but the reaction is strongly grief, not gloating.

Michael@14,

No- it’s clearly not that. George has just, for his own inscrutable reasons, entirely hidden his new relationship. (He’s an engineer, and trying to avoid all those icky personal issues, is my guess)

‘Rehabilitating’ the Germans seems surprising today, it wouldn’t have been then. Americans have long been fond of Germany (no surprise since so many of us have roots there) and the animosity towards the “Japs” in WWII was not mirrored in Europe. (There, the enemy was largely the “Nazi’s”.)

Carlos, though the kitchen has some “unique” features (the table, the trash) the general arrangment isn’t unusual at all. It’s called a “galley” kitchen, and is fairly common from the 30’s on down to today.

Jo reads Papa Schultz’s family as Germans, from Germany. This startled me, because I had always read them as “Pennyslvania Dutch,” that is, Americans of German descent who speak a local dialect of German. Papa wears a lavish beard and he is really, really good at farming under primitive conditions.

When he is first introduced, he uses the word “kinder” to mean “children:”

“One of the kinder saw you going past on the road, so Mama sent me to find you and bring you back to the house for tea and some of her good coffee cake.”

This bit of tile is another clue:

“[The fireplace] was faced with what appeared to be Dutch tile, though I couldn’t believe it. I mean, who is going to import anything as useless as Ornamental tile all the way from Earth? Papa Schultz saw me looking at them and said, ‘My little girl Kathy paints good, huh?'”

Germans from Germany are not ruled out, but in my opinion Heinlein was thinking of the Pennsylvania Dutch. (Though it’s understandable if Jo is not very familiar with them.) In his story “Waldo,” an important character, Gramps Schneider, comes from this subculture.

Bill: “Kinder” is an actual German word. And I certainly wouldn’t recognise that as a US subculture — it’s seems almost cliched typical German to me.

“Farmer in the Sky” broke my sense of disbelief right away when I read it — and I was a teenager then. The society is so wealthy that a 14-year old can own a helicopter and take class trips to Antarctica, so powerful that it is terraforming Jupiter’s moons, yet it is starving? The amount of energy available to human race in “Farmer in the Sky” is staggering — at least one order of magnitude greater than in real life today, and possibly two orders. If human race had that much energy AND had a shortage of food[1], we’d be desalinizing Mediterranean to irrigate Sahara, building skyscraper-size greenhouses, and practicing aquaculture on vast scale. We would NOT be terraforming Ganymede so that few plucky farmers could thumb their noses at Earth. The incongruency was obvious to me even when I was supposedly that book’s intended demographic.

Countless critics had laughed at Golden Age SF stories where Buck Rogers flits from star to star, then pulls a suitcase-size radio out of a cupboard, or laments that nobody had invented a navigation computer small enough to fit in a spaceship. But in all fairness, these Golden Age writers had no reason to expect miniaturized electronics. Heinlein however SHOULD have realized the absurdity of “Farmer in the Sky” premise. Do you suppose he really did not see it, or saw it but refused to let logic get in the way of a pioneer story?

In fact, this kind of technological mismatch that author should have seen was fairly common during Golden Age, and it always irritated me. At the beginning of “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress” Manny mentions (to illustrate generally spartan conditions, IIRC) that “there was not a single power door on Luna [after it has been settled for two generations]”. Given the technological sophistication needed to maintain cities on the Moon, power doors should be a trivial expense — not to mention necessary, in case of pressure failures. Again, even as a teenager I thought it stuck out like a sore thumb.

[1] And were relatively unified, as it seems to be in the book

I have to say the Schultzes seem more German than PA Dutch to me as well. In a way, there’s not enough dialect for them to be from the US. Their speech patterns are very stereotypical for media (good) Germans of the era. Compare the older German couple in Casablanca, for instance.

The Heinlein’s kitchen does look very familiar to anyone who remembers houses that weren’t renovated after the mid-50s. But the first thing that sprang to mind was that the trash connection to an outside receptacle must have been modified very soon after use. They were out on the outskirts of Colorado Springs, IIRC, and raccoons must have been a big problem.

In re pioneering and making sense: there’s no way that the shirt sleeves environment in Time Enough for Love is plausible, but I wouldn’t at all mind a pioneering story set in a future where it’s done as a hobby in an artificial environment.

In re what breaks the suspenders of belief: I just couldn’t keep reading Brin’s Kiln People because I couldn’t imagine how memory consolidation could work and there was no explanation in the book about it.

It’s funny what sticks with you from a writer. The death of Peggy is indeed one of the few really sad deaths in Heinlein’s writing; the death of Karen in Farnham’s Freehold is another. Nancy’s description above is applicable to both of them:

She’s spot on there, whether we’re talking Peggy or Karen. I’m going to think this through and consider other non-heroic deaths in Heinlein.

Just as a data point, my mother’s family in Wisconsin spoke German at the dinner table till my time. They’d been there since the 1830s. It took me a bit to identify “kinder” as a non-English word in that example.

The naming patterns in the family look more Catholic German to my eye than Pennsylvania Dutch — not that Heinlein was very good at the onomastics of characters from cultural groups outside the southern Midwest, with occasional exceptions like Sergei Greenberg in The Star Beast.

I’m reminded of the 1968 movie “Yours, Mine and Ours” in which the father (a Naval officer – hmm!) handled his remarriage -he brought Helen home for a dinner to meet his children and proposed that very night, partially prompted by annoyance at the idea that his children might have reservations about a new mother (who had a lot of children herself).

There’s at least one more death of that sort– one of Maureen’s friends died in childbirth.

I read this for the first time a couple of months ago, and have thought of it as “‘Little House on the Prairie’ in space” ever since. Coming to it as an adult in the 21st century — not only was I not alive when it was written, my mother wasn’t born yet, and my father was a baby! — I cut it slack on things like gender issues, which are pervasive.

(My comment double posted, and I am not seeing a way to delete the extra, only to edit it. And I currently have nothing to add.)

ilya187@20 While I’m reasonably sure it wasn’t Heinlein’s intention, a micromanaged command economy in food but not discretionary goods might explain why there are shortages in the former but not the latter. (Cf. the way the British Empire screwed up food production/distribution in Ireland and India, or the Soviet and Chinese famines in the 20th century.)

More likely, I’d guess a (pre-Green Revolution, Malthusian) underlying assumption that energy wasn’t the primary limiting factor so much as things like arable land, crop yields (which could only slowly be improved by crossbreeding), and those ever-increasing hordes eating whatever gains you made.

If there’s a limit to how much wealth can be usefully applied to food production due to other inputs dominating (which seems a likely tacit assumption, regardless of whether it was right), there’s no reason not to apply the rest to helicopters or spaceships.

Heinlein wrote about microwave cooking prior to Farmer in the Sky; he mentions it in his 1948 novel Space Cadet. See the entry on microwaveable food at http://www.technovelgy.com/ct/content.asp?Bnum=746.

Aside from the difficulty of increasing food production, the Malthusian fears here really reflect a pre-birth-control-pill mindset. And pre- Griswald v. Connecticut, and pre-Roe.

Heinlein assumes that people will have children, and will continue to have a child every year or two, as long as they are sexually active and of childbearing age. He also assumes that birth control, while it may be available, would be an unusual choice.

Instead, as birth control became more available, it also became more popular. To the point that many people these days assume that sex means sex-with-birth-control, unless they’ve specifically decided that they want to try for a child at that time.

And this very much changed the way populations grow. Heinlein was at a point in time when death from childhood diseases had dropped, but the birth rate hadn’t dropped. And he figured that rate of population increase would continue. Instead, we saw that being able to easily choose birth control tends to slow down the increase, once the population feels secure that the infant mortality rate will remain low.

11: many of Heinlein’s ideas about leadership become clear when you realize that as a junior officer, he imprinted on his horrible boss, the future Admiral King.

King, for you non-naval buffs out there, was the guy responsible for the German second “Happy Time” of submarine warfare on our side of the Atlantic during World War Two — he refused to allow merchant convoys or blackouts along the Eastern Seaboard as the British had successfully learned to us, because they were a British invention. About a quarter of all Allied shipping losses during World War Two stems from this decision. Who knows how much shorter the war might have been had the United States followed the British lead? It certainly wouldn’t have been longer.

In addition, King was personally unpleasant to his colleagues and a relentless womanizer, and from the descriptions of his behavior and sleeplessness, I strongly suspect he used amphetamines. Heinlein idolized him. Wouldn’t this be great stuff to learn from the Patterson ‘biography’? You’re not going to find it there, my friends.

CarlosSkullsplitter, why do you think Heinlein imprinted on Admiral King?

I don’t see evidence that Heinlein thought fugheaded stupidity was good, though he did think that chains of command were sometimes essential.

The verbal abuse bit is interesting. In general, Heinlein seemed to think it was cool to be able to comprehensively tell people off, as with Jubal and the police. Offhand, the only time a character regrets reading someone the riot act is Farnham, when he tells Joe off near the end of Farnham’s Freehold.

General point: A great deal of Heinlein is about “Who’s in charge here?”

Aside from the difficulty of increasing food production, the Malthusian

fears here really reflect a pre-birth-control-pill mindset. And pre-

Griswald v. Connecticut, and pre-Roe.

Heinlein assumes that people will have children, and will continue to

have a child every year or two, as long as they are sexually active and

of childbearing age. He also assumes that birth control, while it may

be available, would be an unusual choice.

This suggests that Heinlein never considered French population dynamics of the 19th century, which one might argue was a significant influence on how the events of the first half 0f the 20th century played out. I am 100% ready to consider the hypothesis that France and indeed all Europe was something of a mystery to Heinlein.

33: well, for one thing, the Lexington section of Buell’s biography of King, Master of Sea Power, relies extensively on Heinlein’s warm recollections of King. In fact, Heinlein (according to Patterson) actually dated one of King’s daughters.

I am sure King would be able to rationalize his decision in a manner Heinlein would find acceptable — in fact, I am positive Heinlein would defend it as the correct decision and cut off anyone who disagreed, because that’s how Heinlein behaved. I wonder, in fact, if that’s how King behaved. Assholism is a learned behavior.

Thanks for the evidence.

Figuring out the shifting balance in Heinlein between accomodation to the way things really are (dealing with the Venusians in Space Cadet would be a prime example), wrongheaded high dominance decisions (the father in The Rolling Stones not letting the twins help with the rescue from an accident they were responsible for is my favorite example, but I wouldn’t be surprised if there are plenty more), and appropriate use of authority (the uncle in Rocket Ship Galileo insisting that the boys do science with their amateur rocketry rather than just messing about) would be a large project.

Part of what’s fascinating about Heinlein is that he was only an ass some of the time, and the good stuff in his ideas is not a trivial fraction.

34: and not just Europeans – after all, US birth rates dropped below replacement levels in the 1930s sans a Pill in sight.

Bruce

@29: the problem must be the assumption Perpetually Breeding, since arable land is hardly a problem if it’s a reasonable proposition to turn Ganymedian bare rock into topsoil.

Didn’t Heinlein scoff at contraception as a solution for overpopulation in Tramp Royale? IIRC, he seemed to think it couldn’t scale to an entire population.

I’ve never been able to finish Tramp Royale so I could not say. It seems to me that birth control was actually illegal in parts of the US in the 1950s, or so I seem to recall once having heard, so this might have been like not being able to imagine a phone one could legally turn off.

James@40 I don’t think it could have been that kind of blind spot. Heinlein cites “laws forbidding birth control” in a long list of (bad) effects of organized religion on twentieth century US society in “For Us the Living”, written in 1938, so he’d been conscious of contraception for at least that long. Three years after Farmer in the Sky he wrote Time for the Stars, where global population control (with penalties for extra kids) is a plot point.

Huh: I don’t have Time for the Stars with me, but a quick check in Google Books has Heinlein talking about a lot of the sorts of measures alluded to above: “We have placed a sea in the Sahara, we have melted the Greenland ice cap, we have watered the windy steps, yet each year there is more and more pressure for more and more room for endlessly more people.”

The urge for living with neighbors only at long arms-length is very strong in Heinlein’s work. One could see the crapsack-world aspects of his futures as just a distaste for crowding, “rationalized” into fear of starvation.

I was more struck by Zvi’s comments about corn (maize) being common and wheat rare on Ganymede. While this might seem like a harmless bit of worldbuilding–the things we take for granted, aren’t–it is very difficult to picture a world in which corn will grow plentifully but wheat won’t. It’s my understanding that corn and wheat grow under pretty much the same conditions, to the point where variability in the relative costs lead to substituting one for the other. (Unless we’re positing that the first settlers of Ganymede were all gluten-intolerant and created a corn cartel to prevent the domestic production of wheat.)

Actually (thank you, Michael Pollan), corn uses carbon dioxicide more efficiently than the vast majority of crops. I don’t know whether this was known when Heinlein wrote Farmer on Ganymede, but it might mean that corn would do better in a low pressure atmosphere.

@25: I think you should check the book that movie was “based” on before assuming what was shown on screen was actually correct. I read the book (Who Gets the Drumstick? by Helen and Frank Beardsley) many years ago, and as far as I remember, both parents spent a lot of time making sure both sets of children were happy with the marriage.

Nancy: Patterson talks about Heinlein imprinting on King, he doesn’t talk about King as other than an utterly admirable admiral.

45: Jo, if you check Patterson’s references, you’ll see that he took nearly all his information about King from the forty-seven page letter Heinlein wrote to Buell in 1974 for his biography of King. It’s interesting that Patterson doesn’t use much else from Buell, who had other sources of information about King and the Lexington years — over two hundred retired naval officers who had served with King replied to Buell’s queries in the course of his research — and (if memory serves) nothing from other naval historians on King.

I have been meaning to scan and sort by date the interview references in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. The man had a gift for getting 1970s Hollywood people to open up and tell the most amazing one-of-a-kind stories, but I wonder what his schedule was like, which interviews were the most useful to him as a biographer, etc. (The thought that maybe some of the interviews are a bit too good to be true has crossed my mind, but then storytelling is a Hollywood stock in trade, some listeners are better than others, and many Hollywood people are litigious.)

In the same way, it would be interesting to see which of Heinlein’s letters Patterson relied on the most, since the ‘biography’ so far has been mainly (though not wholly) a background guide to Heinlein’s correspondence. Heinlein’s letter to Buell would certainly be one of them.

I found the passage I had in mind at #39:

Oh, yes, I’ve read the book too – wasn’t suggesting that the movie was true, just that it was another example of the trope Heinlein used in “Farmer” (parents keeping children in the dark about life-changing events like having a new mother or father).

For what it’s worth, I’m not convinced that the demographic transition is stable. Aside from the human race’s hobby of playing “fool the prophet”, birth control probably selects for the tendency to really want children, whether that desire is mostly genetic or mostly memetic.

Heinlein wrote that _Trampe Royale_ passage before the Pill, and when contraception meant clunky barrier methods — and condoms have improved in my active lifetime. Also, people tend to generalise from one example (“Everyone does that…” — Steven Brust) and it does seem to me from having read all his books that perhaps Heinlein himself despite his own childlessness had a kink about “We’re making a baby” and thought everybody did. (In _Friday_ he has Friday ask if Georges could make her pregnant and Georges says saying that has an aphrodisiac effect, whereas I know many people of several genders who wouldn’t react that way.) If you genuinely but mistakenly thought everyone had that kink, and if the only contraception available was barrier methods, I can see thinking that. Also, I have read that the correlation for falling rates of childbirth in country after country is female education. It doesn’t just take birth control, it takes educated women who want lives. I suspect Heinlein would have been delighted by this.

I’m inclined to think it’s literally impossible to find out how much people in general want to have children. There’s so much social pressure in one direction or another, and how many children people want is also very affected by circumstances.

There are clearly some people who desperately want to have children (how many?), and some who don’t want children, but what are the proportions?

Is the number of children people want affected by what the families they grew up in were like? This seems plausible, but people don’t talk about it much as a factor in their preferences.

50: Jo, Heinlein may have had a quirk about the subject, but he could have also read the demographic data about, say, France, as James Nicoll points out — which was a point of military interest of the time, and discussed widely before World War Two.

The French population had been hovering around forty million people since 1870, and only started to increase again in the postwar period, and then mainly by a decline in death rates rather than an increase in birth rates. (The raw birth rates in France today are as low as they have been since World War One.)

Were the French, nominally Catholic and stereotypically passionate, turned off by “barrier methods”?

If memory serve, there are far worse passages in Tramp Royale, but I am away from my copy at the moment. It’s Heinleinian bullheaded ignorance, I’m afraid.

Nancy Lebovitz @@@@@ 22:

Isn’t that one aspect of John Varley’s Steel Beach?

Speaking of condoms as I recall Lazarus denigrates them with the showering in a raincoat phrase in an early appearance; his medical grandfather praises the use – and makes them available – in much later as written though earlier by internal chronology appearance.

Just possibly in context this is another example of making contraception the woman’s responsibility (or arguably choice?)

Carlos @@@@@ 52 asked, ‘Were the French, nominally Catholic and stereotypically passionate, turned off by “barrier methods”?’

The French were renowned throughout Europe for methods of sexual gratification that would not lead to conception.

womzilla — I think the wheat/corn dilemma might be a matter of the amount of arable land required per available food calorie. You can feed a family a maize portion of diet with a kitchen garden (as people still do in places like rural Missouri — the rural locale I happen to know best) and have enough left over to want to sell it — but of course the local markets are saturated at the same time you and your garden are, so there’s no market for it.

Of the dinner scene at the beginning of FitS, different bits from it have drawn themselves to my attention at different times over the years. The part that is making me think at the moment is the “package” of salad in 1950, when it would have been inconceivable to be able to “package” green salads (don’t know whether that’s so much tech as it was expectations0 — and note, no mention of dressing, so it’s supposed to be complet, and how does that work?

For years I wondered how frozen salad could work until I realized it wasn’t being “thawed,” just allowed to come to room temp, so didn’t imply frozen. I remember when packaged, pre-washed greens started showing up in the supers, quite recently.

I remember seeing what Heinlein was doing with the dinner passage and being in awe of it the first time I read it, when I was about 14. I suppose I’d read enough bad writing that this sjumped out at me as the best way to give the reader a description of a (somewhat) different world, in a nice, digestible chunk.

The surprise wedding … I re-read it about a year or so ago and it seemed to me well set up that yeah, it was in some degree a marriage of convenience driven by the fact that both Dad and the new Mrs. wanted the get the hell off earth. It never jarred me that they sprung it on our boy the way they did – parents often announce life-threatening decisions in cavalier fashion – “We’re moving to Calgary!”

Re: surplus energy/terraforming Gany. when we could just do it here on Earth. Seems a valid point, but then he wouldn’t have the atmosphere/pressure subplot and Peggy’s braery etc., Bud’s acceptanc of her as family and a lot of other stuff. Heinlein was just canny enough to have maybe seen this point and just plowed ahead anyway – this is the story he aimed to tell and not one about desalinizing the mediterrranean. First and foremost, at least until near the end, Heinlein was a storyteller and I’d say the bulk of his decisions were made for storytelling purposes. As he said many times, he wasn’t keen on goin gback to real work at his age.

Aside: How much of Heinlein is about pioneering? I’d say more than any other –

and Pa.Dutch/German – whatever, the larger point is still as stated. 1947, identifiably German characters, good guys.

Michael @14:

“… I thought the implication of the hasty marriage was that it was to some extent a marriage of convenience in order for the merged family to be eligible for emigration to Ganymede.”

Actually, no. That’s what Bill thought, too. His father was quite clear:

“Molly and I are not getting married in order to emigrate. We are emigrating because we are getting married. You may be too young to understand it, but I love Molly and Molly loves me. If I wanted to stay here, she’d stay. Since I want to go, she wants to go. She’s wise enough to understand that I need to make a complete break with my old background.”

After reading v 1 of Patterson’s Heinlein biography, I see many of the interpersonal relationships in the books colored by Heinlein’s divorce of Leslyn. The bio has a real way of opening up the fiction to different and previously unconsidered views.

@@@@@36. NancyLebovitz

I’ve commented on this in the comments to Jo’s Rolling Stones review – Just to reiterate: I don’t think you can call Roger’s decision “wrong-headed”. His keeping the twins out of the search is exactly what led to Hazel and Buster being rescued! Direct cause and effect. He sat them out of the drudgery of a grid search, and gave them time to think. They thought, and they solved the problem of where the missing people must have disappeared to. Far from wrong-headed, Roger’s decision looks prescient.

And if you say, well he could not have foreseen that: well, maybe not in so many steps, but he may have had a hunch. If he had a hunch, the fact that it turned out right immunizes Roger from having that decision criticized. And even without a hunch, it is foreseeable that the twins might go off on a wild rescue plan of their own. If they have a grid, then that would jeopardize the search; if they don’t have a grid, no harm done. Again Roger is immunized.

Lay off Roger Stone! :-)

I just finished reading Farmer in the Sky and enjoyed it and Jo Walton’s review (as always). As much as I liked the novel, I was put off a bit by the passages at the end about separating the men from the boys–the resourceful space pioneers vs. the passive stay-at-homes on earth. (There was a similar attitude expressed in Heinlein’s story “It’s Great to be Back.”) But it didn’t seriously mar the book for me–I liked it a lot on the whole.