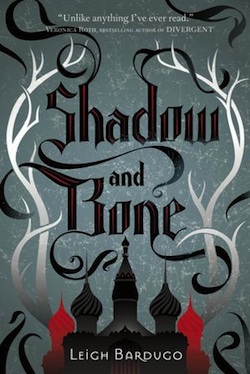

In preparation for the Fierce Reads Tour, we’re showcasing four of the authors and their books this week! Next up we’ve got an excerpt for Leigh Bardugo’s Shadow and Bone out on June 5:

Surrounded by enemies, the once-great nation of Ravka has been torn in two by the Shadow Fold, a swath of near impenetrable darkness crawling with monsters who feast on human flesh. Now its fate may rest on the shoulders of onelonely refugee.

Alina Starkov has never been good at anything. But when her regiment is attacked on the Fold and her best friend is brutally injured, Alina reveals a dormant power that saves his life—a power that could be the key to setting her war-ravaged country free. Wrenched from everything she knows, Alina is whisked away to the royal court to be trained as a member of the Grisha, the magical elite led by the mysterious Darkling.

Yet nothing in this lavish world is what it seems. With darkness looming and an entire kingdom depending on her untamed power, Alina will have to confront the secrets of the Grisha…and the secrets of her heart.

Before

The servants called them malenchki, little ghosts, because they were the smallest and the youngest, and because they haunted the Duke’s house like giggling phantoms, darting in and out of rooms, hiding in cupboards to eavesdrop, sneaking into the kitchen to steal the last of the summer peaches.

The boy and the girl had arrived within weeks of each other, two more orphans of the border wars, dirty-faced refugees plucked from the rubble of distant towns and brought to the Duke’s estate to learn to read and write, and to learn a trade. The boy was short and stocky, shy but always smiling. The girl was different, and she knew it.

Huddled in the kitchen cupboard, listening to the grownups gossip, she heard the Duke’s housekeeper, Ana Kuya, say, “She’s an ugly little thing. No child should look like that. Pale and sour, like a glass of milk that’s turned.”

“And so skinny!” the cook replied. “Never finishes her supper.”

Crouched beside the girl, the boy turned to her and whispered, “Why don’t you eat?”

“Because everything she cooks tastes like mud.”

“Tastes fine to me.”

“You’ll eat anything.”

They bent their ears back to the crack in the cupboard doors.

A moment later the boy whispered, “I don’t think you’re ugly.”

“Shhhh!” the girl hissed. But hidden by the deep shadows of the cupboard, she smiled.

In the summer, they endured long hours of chores followed by even longer hours of lessons in stifling classrooms. When the heat was at its worst, they escaped into the woods to hunt for birds’ nests or swim in the muddy little creek, or they would lie for hours in their meadow, watching the sun pass slowly overhead, speculating on where they would build their dairy farm and whether they would have two white cows or three. In the winter, the Duke left for his city house in Os Alta, and as the days grew shorter and colder, the teachers grew lax in their duties, preferring to sit by the fire and play cards or drink kvas. Bored and trapped indoors, the older children doled out more frequent beatings. So the boy and the girl hid in the disused rooms of the estate, putting on plays for the mice and trying to keep warm.

On the day the Grisha Examiners came, the boy and the girl were perched in the window seat of a dusty upstairs bedroom, hoping to catch a glimpse of the mail coach. Instead, they saw a sleigh, a troika pulled by three black horses, pass through the white stone gates onto the estate. They watched its silent progress through the snow to the Duke’s front door.

Three figures emerged in elegant fur hats and heavy wool kefta: one in crimson, one in darkest blue, and one in vibrant purple.

“Grisha!” the girl whispered.

“Quick!” said the boy.

In an instant, they had shaken off their shoes and were running silently down the hall, slipping through the empty music room and darting behind a column in the gallery that overlooked the sitting room where Ana Kuya liked to receive guests.

Ana Kuya was already there, birdlike in her black dress, pouring tea from the samovar, her large key ring jangling at her waist.

“There are just the two this year, then?” said a woman’s low voice.

They peered through the railing of the balcony to the room below. Two of the Grisha sat by the fire: a handsome man in blue and a woman in red robes with a haughty, refined air. The third, a young blond man, ambled about the room, stretching his legs.

“Yes,” said Ana Kuya. “A boy and a girl, the youngest here by quite a bit. Both around eight, we think.”

“You think?” asked the man in blue.

“When the parents are deceased . . .”

“We understand,” said the woman. “We are, of course, great admirers of your institution. We only wish more of the nobility took an interest in the common people.”

“Our Duke is a very great man,” said Ana Kuya.

Up in the balcony, the boy and the girl nodded sagely to each other. Their benefactor, Duke Keramsov, was a celebrated war hero and a friend to the people. When he had returned from the front lines, he converted his estate into an orphanage and a home for war widows. They were told to keep him nightly in their prayers.

“And what are they like, these children?” asked the woman.

“The girl has some talent for drawing. The boy is most at home in the meadow and the wood.”

“But what are they like?” repeated the woman.

Ana Kuya pursed her withered lips. “What are they like? They are undisciplined, contrary, far too attached to each other. They—”

“They are listening to every word we say,” said the young man in purple.

The boy and the girl jumped in surprise. He was staring directly at their hiding spot. They shrank behind the column, but it was too late.

Ana Kuya’s voice lashed out like a whip. “Alina Starkov! Malyen Oretsev! Come down here at once!”

Reluctantly, Alina and Mal made their way down the narrow spiral staircase at the end of the gallery. When they reached the bottom, the woman in red rose from her chair and gestured them forward.

“Do you know who we are?” the woman asked. Her hair was steel gray. Her face lined, but beautiful.

“You’re witches!” blurted Mal.

“Witches?” she snarled. She whirled on Ana Kuya. “Is that what you teach at this school? Superstition and lies?”

Ana Kuya flushed with embarrassment. The woman in red turned back to Mal and Alina, her dark eyes blazing. “We are not witches. We are practitioners of the Small Science. We keep this country and this kingdom safe.”

“As does the First Army,” Ana Kuya said quietly, an unmistakeable edge to her voice.

The woman in red stiffened, but after a moment she conceded, “As does the King’s Army.”

The young man in purple smiled and knelt before the children. He said gently, “When the leaves change color, do you call it magic? What about when you cut your hand and it heals? And when you put a pot of water on the stove and it boils, is it magic then?”

Mal shook his head, his eyes wide.

But Alina frowned and said, “Anyone can boil water.”

Ana Kuya sighed in exasperation, but the woman in red laughed.

“You’re very right. Anyone can boil water. But not just anyone can master the Small Science. That’s why we’ve come to test you.” She turned to Ana Kuya. “Leave us now.”

“Wait!” exclaimed Mal. “What happens if we’re Grisha? What happens to us?”

The woman in red looked down at them. “If, by some small chance, one of you is Grisha, then that lucky child will go to a special school where Grisha learn to use their talents.”

“You will have the finest clothes, the finest food, whatever your heart desires,” said the man in purple. “Would you like that?”

“It is the greatest way that you may serve your King,” said Ana Kuya, still hovering by the door.

“That is very true,” said the woman in red, pleased and willing to make peace.

The boy and the girl glanced at each other and, because the adults were not paying close attention, they did not see the girl reach out to clasp the boy’s hand or the look that passed between them. The Duke would have recognized that look. He had spent long years on the ravaged northern borders, where the villages were constantly under siege and the peasants fought their battles with little aid from the King or anyone else. He had seen a woman, barefoot and unflinching in her doorway, face down a row of bayonets. He knew the look of a man defending his home with nothing but a rock in his hand.

CHAPTER 1

Standing on the edge of a crowded road, I looked down onto the rolling fields and abandoned farms of the Tula Valley and got my first glimpse of the Shadow Fold. My regiment was two weeks’ march from the military encampment at Poliznaya and the autumn sun was warm overhead, but I shivered in my coat as I eyed the haze that lay like a dirty smudge on the horizon.

A heavy shoulder slammed into me from behind. I stumbled and nearly pitched face-first into the muddy road.

“Hey!” shouted the soldier. “Watch yourself!”

“Why don’t you watch your fat feet?” I snapped, and took some satisfaction from the surprise that came over his broad face. People, particularly big men carrying big rifles, don’t expect lip from a scrawny thing like me. They always look a bit dazed when they get it.

The soldier got over the novelty quickly and gave me a dirty look as he adjusted the pack on his back, then disappeared into the caravan of horses, men, carts, and wagons streaming over the crest of the hill and into the valley below.

I quickened my steps, trying to peer over the crowd. I’d lost sight of the yellow flag of the surveyors’ cart hours ago, and I knew I was far behind.

As I walked, I took in the green and gold smells of the autumn wood, the soft breeze at my back. We were on the Vy, the wide road that had once led all the way from Os Alta to the wealthy port cities on Ravka’s western coast. But that was before the Shadow Fold.

Somewhere in the crowd, someone was singing. Singing? What idiot is singing on his way into the Fold? I glanced again at that smudge on the horizon and had to suppress a shudder. I’d seen the Shadow Fold on many maps, a black slash that had severed Ravka from its only coastline and left it landlocked. Sometimes it was shown as a stain, sometimes as a bleak and shapeless cloud. And then there were the maps that just showed the Shadow Fold as a long, narrow lake and labeled it by its other name, “the Unsea,” a name intended to put soldiers and merchants at their ease and encourage crossings.

I snorted. That might fool some fat merchant, but it was little comfort to me.

I tore my attention from the sinister haze hovering in the distance and looked down onto the ruined farms of the Tula. The valley had once been home to some of Ravka’s richest estates. One day it was a place where farmers tended crops and sheep grazed in green fields. The next, a dark slash had appeared on the landscape, a swath of nearly impenetrable darkness that grew with every passing year and crawled with horrors. Where the farmers had gone, their herds, their crops, their homes and families, no one knew.

Stop it, I told myself firmly. You’re only making things worse. People have been crossing the Fold for years . . . usually with massive casualties, but all the same. I took a deep breath to steady myself.

“No fainting in the middle of the road,” said a voice close to my ear as a heavy arm landed across my shoulders and gave me a squeeze. I looked up to see Mal’s familiar face, a smile in his bright blue eyes as he fell into step beside me. “C’mon,” he said. “One foot in front of the other. You know how it’s done.”

“You’re interfering with my plan.”

“Oh really?”

“Yes. Faint, get trampled, grievous injuries all around.”

“That sounds like a brilliant plan.”

“Ah, but if I’m horribly maimed, I won’t be able to cross the Fold.”

Mal nodded slowly. “I see. I can shove you under a cart if that would help.”

“I’ll think about it,” I grumbled, but I felt my mood lifting all the same. Despite my best efforts, Mal still had that effect on me. And I wasn’t the only one. A pretty blond girl strolled by and waved, throwing Mal a flirtatious glance over her shoulder.

“Hey, Ruby,” he called. “See you later?”

Ruby giggled and scampered off into the crowd. Mal grinned broadly until he caught my eye roll.

“What? I thought you liked Ruby.”

“As it happens, we don’t have much to talk about,” I said drily. I actually had liked Ruby—at first. When Mal and I left the orphanage at Keramzin to train for our military service in Poliznaya, I’d been nervous about meeting new people. But lots of girls had been excited to befriend me, and Ruby had been among the most eager. Those friendships lasted as long as it took me to figure out that their only interest in me lay in my proximity to Mal.

Now I watched him stretch his arms expansively and turn his face up to the autumn sky, looking perfectly content. There was even, I noted with some disgust, a little bounce in his step.

“What is wrong with you?” I whispered furiously.

“Nothing,” he said, surprised. “I feel great.”

“But how can you be so . . . so jaunty?”

“Jaunty? I’ve never been jaunty. I hope never to be jaunty.”

“Well, then what’s all this?” I asked, waving a hand at him. “You look like you’re on your way to a really good dinner instead of possible death and dismemberment.”

Mal laughed. “You worry too much. The King’s sent a whole group of Grisha pyros to cover the skiffs, and even a few of those creepy Heartrenders. We have our rifles,” he said, patting the one on his back. “We’ll be fine.”

“A rifle won’t make much difference if there’s a bad attack.”

Mal gave me a bemused glance. “What’s with you lately? You’re even grumpier than usual. And you look terrible.”

“Thanks,” I groused. “I haven’t been sleeping well.”

“What else is new?”

He was right, of course. I’d never slept well. But it had been even worse over the last few days. Saints knew I had plenty of good reasons to dread going into the Fold, reasons shared by every member of our regiment who had been unlucky enough to be chosen for the crossing. But there was something else, a deeper feeling of unease that I couldn’t quite name.

I glanced at Mal. There had been a time when I could have told him anything. “I just . . . have this feeling.”

“Stop worrying so much. Maybe they’ll put Mikhael on the skiff. The volcra will take one look at that big juicy belly of his and leave us alone.”

Unbidden, a memory came to me: Mal and I, sitting side by side in a chair in the Duke’s library, flipping through the pages of a large leather-bound book. We’d happened on an illustration of a volcra: long, filthy claws; leathery wings; and rows of razor-sharp teeth for feasting on human flesh. They were blind from generations spent living and hunting in the Fold, but legend had it they could smell human blood from miles away. I’d pointed to the page and asked, “What is it holding?”

I could still hear Mal’s whisper in my ear. “I think—I think it’s a foot.” We’d slammed the book shut and run squealing out into the safety of the sunlight. . . .

Without realizing it, I’d stopped walking, frozen in place, unable to shake the memory from my mind. When Mal realized I wasn’t with him, he gave a great beleaguered sigh and marched back to me. He rested his hands on my shoulders and gave me a little shake.

“I was kidding. No one’s going to eat Mikhael.”

“I know,” I said, staring down at my boots. “You’re hilarious.”

“Alina, come on. We’ll be fine.”

“You can’t know that.”

“Look at me.” I willed myself to raise my eyes to his. “I know you’re scared. I am, too. But we’re going to do this, and we’re going to be fine. We always are. Okay?” He smiled, and my heart gave a very loud thud in my chest.

I rubbed my thumb over the scar that ran across the palm of my right hand and took a shaky breath. “Okay,” I said grudgingly, and I actually felt myself smiling back.

“Madam’s spirits have been restored!” Mal shouted. “The sun can once more shine!”

“Oh will you shut up?”

I turned to give him a punch, but before I could, he’d grabbed hold of me and lifted me off my feet. A clatter of hooves and shouts split the air. Mal yanked me to the side of the road just as a huge black coach roared past, scattering people before it as they ran to avoid the pounding hooves of four black horses. Beside the whip-wielding driver perched two soldiers in charcoal coats.

The Darkling. There was no mistaking his black coach or the uniform of his personal guard.

Another coach, this one lacquered red, rumbled past us at a more leisurely pace.

I looked up at Mal, my heart racing from the close call. “Thanks,” I whispered. Mal suddenly seemed to realize that he had his arms around me. He let go and hastily stepped back. I brushed the dust from my coat, hoping he wouldn’t notice the flush on my cheeks.

A third coach rolled by, lacquered in blue, and a girl leaned out the window. She had curling black hair and wore a hat of silver fox. She scanned the watching crowd and, predictably, her eyes lingered on Mal.

You were just mooning over him, I chided myself. Why shouldn’t some gorgeous Grisha do the same?

Her lips curled into a small smile as she held Mal’s gaze, watching him over her shoulder until the coach was out of sight. Mal goggled dumbly after her, his mouth slightly open.

“Close your mouth before something flies in,” I snapped.

Mal blinked, still looking dazed.

“Did you see that?” a voice bellowed. I turned to see Mikhael loping toward us, wearing an almost comical expression of awe. Mikhael was a huge redhead with a wide face and an even wider neck. Behind him, Dubrov, reedy and dark, hurried to catch up. They were both trackers in Mal’s unit and never far from his side.

“Of course I saw it,” Mal said, his dopey expression evaporating into a cocky grin. I rolled my eyes.

“She looked right at you!” shouted Mikhael, clapping Mal on the back.

Mal gave a casual shrug, but his smile widened. “So she did,” he said smugly.

Dubrov shifted nervously. “They say Grisha girls can put spells on you.”

I snorted.

Mikhael looked at me as if he hadn’t even known I was there. “Hey, Sticks,” he said, and gave me a little jab on the arm. I scowled at the nickname, but he had already turned back to Mal. “You know she’ll be staying at camp,” he said with a leer.

“I hear the Grisha tent’s as big as a cathedral,” added Dubrov.

“Lots of nice shadowy nooks,” said Mikhael, and actually waggled his brows.

Mal whooped. Without sparing me another glance, the three of them strode off, shouting and shoving one another.

“Great seeing you guys,” I muttered under my breath. I readjusted the strap of the satchel slung across my shoulders and started back down the road, joining the last few stragglers down the hill and into Kribirsk. I didn’t bother to hurry. I’d probably get yelled at when I finally made it to the Documents Tent, but there was nothing I could do about it now.

I rubbed my arm where Mikhael had punched me. Sticks. I hated that name. You didn’t call me Sticks when you were drunk on kvas and trying to paw me at the spring bonfire, you miserable oaf, I thought spitefully.

Kribirsk wasn’t much to look at. According to the Senior Cartographer, it had been a sleepy market town in the days before the Shadow Fold, little more than a dusty main square and an inn for weary travelers on the Vy. But now it had become a kind of ramshackle port city, growing up around a permanent military encampment and the drydocks where the sandskiffs waited to take passengers through the darkness to West Ravka. I passed taverns and pubs and what I was pretty sure were brothels meant to cater to the troops of the King’s Army. There were shops selling rifles and crossbows, lamps and torches, all necessary equipment for a trek across the Fold. The little church with its whitewashed walls and gleaming onion domes was in surprisingly good repair. Or maybe not so surprising, I considered. Anyone contemplating a trip across the Shadow Fold would be smart to stop and pray.

I found my way to where the surveyors were billeted, deposited my pack on a cot, and hurried over to the Documents Tent. To my relief, the Senior Cartographer was nowhere in sight, and I was able to slip inside unseen.

Entering the white canvas tent, I felt myself relax for the first time since I’d caught sight of the Fold. The Documents Tent was essentially the same in every camp I’d seen, full of bright light and rows of drafting tables where artists and surveyors bent to their work. After the noise and jostle of the journey, there was something soothing about the crackle of paper, the smell of ink, and the soft scratching of nibs and brushes.

I pulled my sketchbook from my coat pocket and slid onto a workbench beside Alexei, who turned to me and whispered irritably, “Where have you been?”

“Nearly getting trampled by the Darkling’s coach,” I replied, grabbing a clean piece of paper and flipping through my sketches to try to find a suitable one to copy. Alexei and I were both junior cartographers’ assistants and, as part of our training, we had to submit two finished sketches or renderings at the end of every day.

Alexei drew in a sharp breath. “Really? Did you actually see him?”

“Actually, I was too busy trying not to die.”

“There are worse ways to go.” He caught sight of the sketch of a rocky valley I was about to start copying. “Ugh. Not that one.” He flipped through my sketchbook to an elevation of a mountain ridge and tapped it with his finger. “There.”

I barely had time to put pen to paper before the Senior Cartographer entered the tent and came swooping down the aisle, observing our work as he passed.

“I hope that’s the second sketch you’re starting, Alina Starkov.”

“Yes,” I lied. “Yes, it is.”

As soon as the Cartographer had passed on, Alexei whispered, “Tell me about the coach.”

“I have to finish my sketches.”

“Here,” he said in exasperation, sliding one of his sketches over to me.

“He’ll know it’s your work.”

“It’s not that good. You should be able to pass it off as yours.”

“Now there’s the Alexei I know and tolerate,” I grumbled, but I didn’t give back the sketch. Alexei was one of the most talented assistants and he knew it.

Alexei extracted every last detail from me about the three Grisha coaches. I was grateful for the sketch, so I did my best to satisfy his curiosity as I finished up my elevation of the mountain ridge and worked in my thumb measurements of some of the highest peaks.

By the time we were finished, dusk was falling. We handed in our work and walked to the mess tent, where we stood in line for muddy stew ladled out by a sweaty cook and found seats with some of the other surveyors.

I passed the meal in silence, listening to Alexei and the others exchange camp gossip and jittery talk about tomorrow’s crossing. Alexei insisted that I retell the story of the Grisha coaches, and it was met by the usual mix of fascination and fear that greeted any mention of the Darkling.

“He’s not natural,” said Eva, another assistant; she had pretty green eyes that did little to distract from her piglike nose. “None of them are.”

Alexei sniffed. “Please spare us your superstition, Eva.”

“It was a Darkling who made the Shadow Fold to begin with.”

“That was hundreds of years ago!” protested Alexei. “And that Darkling was completely mad.”

“This one is just as bad.”

“Peasant,” Alexei said, and dismissed her with a wave. Eva gave him an affronted look and deliberately turned away from him to talk to her friends.

I stayed quiet. I was more a peasant than Eva, despite her superstitions. It was only by the Duke’s charity that I could read and write, but by unspoken agreement, Mal and I avoided mentioning Keramzin.

As if on cue, a raucous burst of laughter pulled me from my thoughts. I looked over my shoulder. Mal was holding court at a rowdy table of trackers.

Alexei followed my glance. “How did you two become friends anyway?”

“We grew up together.”

“You don’t seem to have much in common.”

I shrugged. “I guess it’s easy to have a lot in common when you’re kids.” Like loneliness, and memories of parents we were meant to forget, and the pleasure of escaping chores to play tag in our meadow.

Alexei looked so skeptical that I had to laugh. “He wasn’t always the Amazing Mal, expert tracker and seducer of Grisha girls.”

Alexei’s jaw dropped. “He seduced a Grisha girl?”

“No, but I’m sure he will,” I muttered.

“So what was he like?”

“He was short and pudgy and afraid of baths,” I said with some satisfaction.

Alexei glanced at Mal. “I guess things change.”

I rubbed my thumb over the scar in my palm. “I guess they do.”

We cleared our plates and drifted out of the mess tent into the cool night. On the way back to the barracks, we took a detour so that we could walk by the Grisha camp. The Grisha pavilion really was the size of a cathedral, covered in black silk, its blue, red, and purple pennants flying high above. Hidden somewhere behind it were the Darkling’s tents, guarded by Corporalki Heartrenders and the Darkling’s personal guard.

When Alexei had looked his fill, we wended our way back to our quarters. Alexei got quiet and started cracking his knuckles, and I knew we were both thinking about tomorrow’s crossing. Judging by the gloomy mood in the barracks, we weren’t alone. Some people were already on their cots, sleeping—or trying to—while others huddled by lamplight, talking in low tones. A few sat clutching their icons, praying to their Saints.

I unfurled my bedroll on a narrow cot, removed my boots, and hung up my coat. Then I wriggled down into the fur-lined blankets and stared up at the roof, waiting for sleep. I stayed that way for a long time, until the lamplights had all been extinguished and the sounds of conversation gave way to soft snores and the rustle of bodies.

Tomorrow, if everything went as planned, we would pass safely through to West Ravka, and I would get my first glimpse of the True Sea. There, Mal and the other trackers would hunt for red wolves and sea foxes and other coveted creatures that could only be found in the west. I would stay with the cartographers in Os Kervo to finish my training and help draft whatever information we managed to glean in the Fold. And then, of course, I’d have to cross the Fold again in order to return home. But it was hard to think that far ahead.

I was still wide awake when I heard it. Tap tap. Pause. Tap. Then again: Tap tap. Pause. Tap.

“What’s going on?” mumbled Alexei drowsily from the cot nearest mine.

“Nothing,” I whispered, already slipping out of my bedroll and shoving my feet into my boots.

I grabbed my coat and crept out of the barracks as quietly as I could. As I opened the door I heard a giggle, and a female voice called from somewhere in the dark room, “If it’s that tracker, tell him to come inside and keep me warm.”

“If he wants to catch tsifil, I’m sure you’ll be his first stop,” I said sweetly, and slipped out into the night.

The cold air stung my cheeks and I buried my chin in my collar, wishing I’d taken the time to grab my scarf and gloves. Mal was sitting on the rickety steps, his back to me. Beyond him, I could see Mikhael and Dubrov passing a bottle back and forth beneath the glowing lights of the footpath.

I scowled. “Please tell me you didn’t just wake me up to inform me that you’re going to the Grisha tent. What do you want, advice?”

“You weren’t sleeping. You were lying awake worrying.”

“Wrong. I was planning how to sneak into the Grisha pavilion and snag myself a cute Corporalnik.”

Mal laughed. I hesitated by the door. This was the hardest part of being around him—other than the way he made my heart do clumsy acrobatics. I hated hiding how much the stupid things he did hurt me, but I hated the idea of him finding out even more. I thought about just turning around and going back inside. Instead, I swallowed my jealousy and sat down beside him.

“I hope you brought me something nice,” I said. “Alina’s Secrets of Seduction do not come cheap.”

He grinned. “Can you put it on my tab?”

“I suppose. But only because I know you’re good for it.”

I peered into the dark and watched Dubrov take a swig from the bottle and then lurch forward. Mikhael put his arm out to steady him, and the sounds of their laughter floated back to us on the night air.

Mal shook his head and sighed. “He always tries to keep up with Mikhael. He’ll probably end up puking on my boots.”

“Serves you right,” I said. “So what are you doing here?” When we’d first started our military service a year ago, Mal had visited me almost every night. But he hadn’t come by in months.

He shrugged. “I don’t know. You looked so miserable at dinner.”

I was surprised he’d noticed. “Just thinking about the crossing,” I said carefully. It wasn’t exactly a lie. I was terrified of entering the Fold, and Mal definitely didn’t need to know that Alexei and I had been talking about him. “But I’m touched by your concern.”

“Hey,” he said with a grin, “I worry.”

“If you’re lucky, a volcra will have me for breakfast tomorrow and then you won’t have to fret anymore.”

“You know I’d be lost without you.”

“You’ve never been lost in your life,” I scoffed. I was the mapmaker, but Mal could find true north blindfolded and standing on his head.

He bumped his shoulder against mine. “You know what I mean.”

“Sure,” I said. But I didn’t. Not really.

We sat in silence, watching our breath make plumes in the cold air.

Mal studied the toes of his boots and said, “I guess I’m nervous, too.”

I nudged him with my elbow and said with confidence I didn’t feel, “If we can take on Ana Kuya, we can handle a few volcra.”

“If I remember right, the last time we crossed Ana Kuya, you got your ears boxed and we both ended up mucking out the stables.”

I winced. “I’m trying to be reassuring. You could at least pretend I’m succeeding.”

“You know the funny thing?” he asked. “I actually miss her sometimes.”

I did my best to hide my astonishment. We’d spent more than ten years of our lives in Keramzin, but usually I got the impression that Mal wanted to forget everything about the place, maybe even me. There he’d been another lost refugee, another orphan made to feel grateful for every mouthful of food, every used pair of boots. In the army, he’d carved out a real place for himself where no one needed to know that he’d once been an unwanted little boy.

“Me too,” I admitted. “We could write to her.”

“Maybe,” Mal said.

Suddenly, he reached out and took hold of my hand. I tried to ignore the little jolt that went through me. “This time tomorrow, we’ll be sitting in the harbor at Os Kervo, looking out at the ocean and drinking kvas.”

I glanced at Dubrov weaving back and forth and smiled. “Is Dubrov buying?”

“Just you and me,” Mal said.

“Really?”

“It’s always just you and me, Alina.”

For a moment, it seemed like it was true. The world was this step, this circle of lamplight, the two of us suspended in the dark.

“Come on!” bellowed Mikhael from the path.

Mal started like a man waking from a dream. He gave my hand a last squeeze before he dropped it. “Gotta go,” he said, his brash grin sliding back into place. “Try to get some sleep.”

He hopped lightly from the stairs and jogged off to join his friends. “Wish me luck!” he called over his shoulder.

“Good luck,” I said automatically and then wanted to kick myself. Good luck? Have a lovely time, Mal. Hope you find a pretty Grisha, fall deeply in love, and make lots of gorgeous, disgustingly talented babies together.

I sat frozen on the steps, watching them disappear down the path, still feeling the warm pressure of Mal’s hand in mine. Oh well, I thought as I got to my feet. Maybe he’ll fall into a ditch on his way there.

I edged back into the barracks, closed the door tightly behind me, and gratefully snuggled into my bedroll.

Would that black-haired Grisha girl sneak out of the pavilion to meet Mal? I pushed the thought away. It was none of my business, and really, I didn’t want to know. Mal had never looked at me the way he’d looked at that girl or even the way he looked at Ruby, and he never would. But the fact that we were still friends was more important than any of that.

For how long? said a nagging voice in my head. Alexei was right: things change. Mal had changed for the better. He’d gotten handsomer, braver, cockier. And I’d gotten . . . taller. I sighed and rolled onto my side. I wanted to believe that Mal and I would always be friends, but I had to face the fact that we were on different paths. Lying in the dark, waiting for sleep, I wondered if those paths would just keep taking us further and further apart, and if a day might come when we would be strangers to each other once again.

Shadow and Bone © Leigh Bardugo 2012