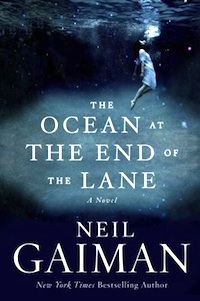

Neil Gaiman returns to familiar territory with his much-anticipated novel, The Ocean at the End of the Lane, forthcoming from William Morrow on June 18. The story explores the dark spaces of myth, memory, and identity through the experiences of a young boy, recalled by his adult self upon a visit to the place where he grew up—the place where he brushed something larger, more grand and impossible, than himself. As the flap copy says, “When he was seven years old, he found himself in unimaginable danger—from inside his family, and from without. His only hope is the girl who lives at the end of the lane. She says her duck pond is an ocean. She may be telling the truth. After all, her grandmother remembers the Big Bang.”

The flap copy perhaps misrepresents the tone of this novel; it sounds all together more playful than this sharp, poignant, and occasionally somber tale actually is. The Ocean at the End of the Lane is Gaiman’s first novel directed toward adults since 2005’s Anansi Boys, but within it, he creates a curious tonal hybrid: the narrative is framed by an adult voice, and the content of the story is frequently outside of what would be seen in a children’s book—yet, the majority of the tale is told as by a child, with a child’s eyes and sense of storytelling. It is as if this novel settles on a middle-ground between Gaiman’s various potential audiences.

Though I generally shy from the use of descriptions like “Gaiman-esque”—what does that actually signify, after all?—in this case, it seems apt. The Ocean at the End of the Lane is headily reminiscent of other works in Gaiman’s oeuvre, though it takes a different angle on questions about identity, family, and darkness than its predecessors. I was particularly reminded of Coraline, structurally and thematically: both revolve around a young child whose home and life are invaded by something other-worldly that travels eldritch paths between realms to wreak havoc on their family, the child’s own discovery of the lines between courage and terror in attempting to undo the damage and enact a rescue, the sense that a child is somehow significantly apart from the world of adults and cannot communicate with them, and so on. (Not to mention more minor echoes, such as the black kittens that may or may not be liable to talk.)

The differences, however, are where the resonance of The Ocean at the End of the Lane lies. Given that the narrator, in this case, is actually an adult—entranced by memories suddenly returned to him—how the story is framed and what details are given, as well as how they are analyzed by the narrator himself, has a flavor unto itself that Coraline or Gaiman’s other books directed to children don’t. Here, he touches briefly and with the effect of reminiscence on scenes of horror and brutality, painting them more with the brush of implication and distance than that of direct involvement—and yet, this effect turns what might otherwise be simply frightening scenes into deeply discomfiting, haunting moments.

This distancing effect also allows Gaiman to employ and translate experiences from his own childhood, creating a sense of vulnerable realism—a realism that, in the context of this particular story, makes the supernatural seem that much more believable and terrifying. The confusion and interplay between the real and the mythic is what makes much of Gaiman’s work function, and this novel is no exception. It is, certainly, in the mythic mode; the narrator makes a journey of the mind at the opening, back to the brief days in his childhood where his life brushed up against something vast and unimaginable, and then returns to himself, shedding those selfsame memories as he re-enters the staid world of his contemporary present. The structure and effect of this, a sort of underworld journey, plays deeply with aspects of identity and memory that Gaiman often visits in his work.

The novel is also, unsurprisingly, a story about stories and language—about narrative, really, and the frameworks of reality erected with it. And, equally, it is about a child who loved books and who eventually became an artist himself. “Books were safer than people anyway,” reflects the narrator at one point. Or, more to the point and evocative for this particular reader, “I was not happy as a child, although from time to time I was content. I lived in books more than I lived anywhere else.” These are the moments of sharp honesty that evoke a powerful response in the reader who has, perhaps, shared a similar history—I am reminded, in a crosswise fashion, of my own responses to Jo Walton’s recent Among Others—and therefore reinforce the realism of the piece as it interweaves with the mythic. There are further scenes that function in both directions, such as the scene where Lettie Hempstock attempts to sing the monster’s bindings, about which the narrator comments:

…once I dreamed I kept a perfect little bed-and-breakfast by the seaside, and to everyone who came to stay with me I would say, in that tongue, “Be whole,” and they would become whole, not be broken people, not any longer, because I had spoken the language of shaping.

This concern with the ways that stories make the world, make people, grow hearts, and heal—that’s familiar, too, but not wearying to see again.

Gaiman, in The Ocean at the End of the Lane, is circling the themes and curiosities that have haunted his art from early on—questions that he continues to find alternate answers to, or different ways to ask them of the reader and potentially also himself. That sense of echo, of the familiar rendered in a sideways or strange manner, opens up the vista of imagination, much as the mythic mode of storytelling does, to allow the reader to drink deeply of the imagery and potentiality of the tale. It is a compact story—held side to side with my copy of American Gods, it’s barely a third of the size—but does not need further space to make its imprint. The prose is rich, as I always expect; powerful imagery both delights and horrifies; the messages of the book rise up gently and submerge again as the story unfolds.

And, finally, as the narrator walks then drives away from the farm at the end of the lane—as the otherwise world fades alongside his memories of it, as he returns to the world he knows as “real”—the reader encounters a sense of silence, a silence that is still thick with possibilities and knowledge yet to be unearthed, stories yet to be told. That series of narrative effects, resonances and echoes and a closing silence, make this novel—potentially unassuming, small, familiar in theme and tone—remarkable and, I would assert with some confidence, subtly haunting. It’s not a tour de force; instead, it’s a slower and more cautious piece that, nonetheless, illustrates quite thoroughly why Stephen King has called Gaiman “a treasure house of story.”

The Ocean at the End of the Lane is out on June 18 from William Morrow

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.