Last week, NASA and MIT researchers announced that they plan to expand the ongoing search for Earth-like planets outside of our solar system. “TESS”—the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite—will search for possible alternate Earths by looking for changes in brightness as planets travel in their orbits between their suns and the satellite’s line of vision. It’s a pretty rough way to find a substitute home planet, but what if TESS really does happen upon an extrasolar body that might be comfortable enough for our species to eventually colonize? Might there already be life on such a planet, and might any of that life look familiar to us? Say, like dinosaurs?

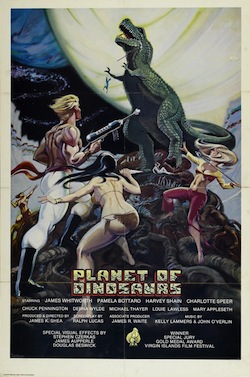

Venusian sauropods and other forms of space dinosaur have popped up in sci-fi from time to time. And an otherwise mundane biochemistry paper published by the Journal of the American Chemical Society—and later retracted for reasons of self-plagiarism—tried to pump up its profile by speculating that alien life might look like “advanced versions of dinosaurs.” But, cheesy as it is, my favorite take on the idea is 1978’s schlocky Planet of Dinosaurs. (Not “of the Dinosaurs,” but “of Dinosaurs,” which sounds like a planet assembled from miscellaneous stegosaur and ceratopsid parts.)

In the film, a bickering, be-jumpsuited group of space travelers crash lands on a world where the whole of Mesozoic dinosaur diversity is squashed down into the same time period—the film’s ever-hungry Tyrannosaurus snacks on a Stegosaurus at one point, even though the dinosaurs actually lived over 80 million years apart. (Yes, yes, I know, this is science fiction. Let me have my paleo pedant fun.)

But why are there dinosaurs on the planet at all? The movie takes care of the problematic premise after the shipwrecked crew stumbles across a “Brontosaurus.” The uncharted planet is so similar to Earth, fictional Captain Lee Norsythe explains, that life must have followed the same evolutionary script. By arriving on a planet in the midst of the Mesozoic, the lost crew effectively traveled back in time.

Too bad the whole premise is bunk.

Evolution does not follow predetermined pathways. We might like to think so—to see some inevitability to our origin on this planet, at least—but the truth is that evolutionary history is a contingent phenomenon that is as much influenced by time and chance as the directing force of natural selection.

If life were to start all over again, in the “rewinding the evolutionary tape” thought experiment the late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould once proposed, there’d be no reason to expect that the following 3.4 billion years of evolution would unfold in the same way. Unpredictable elements of biology and interactions between individuals would create an alternate evolutionary universe where dinosaurs—much less our species or any other familiar organism—probably never would have existed.

Mass extinctions are test cases for how deeply the big picture of evolution is influenced by unforeseen events. There have been five major mass extinctions in the history of life on Earth, and three of these directly affected the origin and decimation of dinosaurs.

Just prior to 250 million years ago, our varied protomammal cousins and ancestors—properly known as synapsids—were the dominant vertebrates on land. The synapsids included everything from tusked, barrel-bodied dicynodonts to saber-fanged, dog-like gorgonopsians and the rather cute, shuffling cynodonts, among others. But right at their peak, the synapsids were almost totally wiped out by the worst biological catastrophe of all time. Fantastic volcanic outpouring altered the atmosphere, spurring a chain reaction of events that further warmed the globe, and acidified the seas, wiping out over 95% of known species in the seas and 70% of known terrestrial vertebrates. This was the end-Permian mass extinction.

The survivors of this mass extinction proliferated into empty niches, including the archaic ancestors of dinosaurs. Indeed, the earliest possible dinosaur is dated to about 245 million years old, a relatively scant five million years after the disaster. But dinosaurs did not immediately become dominant.

Dinosaurs were one lineage in a bigger group called the Archosauria—the “ruling reptiles” that also included pterosaurs, crocodiles, and their closest relatives. And during the Triassic—the period following the Permian—the crocodile cousins were the most prominent creatures on the landscape. The superficially gharial-like phytosaurs, the “armadillodile” aetosaurs, vicious rauisuchids, and other forms of crocodile relatives dominated Triassic landscapes, while both dinosaurs and surviving synapsids—including some of our ancestors—were relatively rare, marginal, and small by comparison.

It took another mass extinction to give dinosaurs their shot. About 201 million years ago, at the end of the Triassic, volcanic activity and climate change again conspired to cut back global biodiversity. This time, the crocodile cousins were severely cut back, while dinosaurs seemingly made it through the changes unscathed. Finally, at the beginning of the Jurassic about 200 million years ago, dinosaurs truly started to rule the world. That is, until another mass extinction 134 million years later eliminated all but that specialized, feathery dinosaur lineage we know as birds. If nothing else, this is proof that nature is totally indifferent to natural awesomeness, otherwise the great non-avian dinosaurs might have been spared.

Mass extinctions—events contingent on a combination of natural phenomena coming together in deadly synergy—gave dinosaurs their evolutionary shot and almost entirely destroyed the famous group. It’s not as if dinosaurs were destined to be, or there was a foreordained tempo to their extinction. Like all species, they were molded by time and chance. And the same would be true on any other planet.

If there is some form of life elsewhere in the universe—and I see no reason why there shouldn’t be—then there’s no reason to expect space dinosaurs, or any other familiar animals from modern or fossil life. Started from scratch under different conditions, life will evolve along unexpected pathways. Then again, should astronauts someday step off their landing vessel and come face-to-face with a fuzzy alien tyrannosaur, they will probably have just a few moments to ponder why evolution replayed itself before they get crunched.

If we ever discover alien life, it will be a landmark test about how evolution works and whether there are common patterns in the history of Life. There’s no evidence or even sound line of logic to suppose that space dinosaurs, or anything like them, actually exists, but if such creatures someday trot across a rover’s field of view, the animals would open up a slew of evolutionary questions and create what will have to be the best job of all time—astrodinosaurology.

Brian Switek is the author of My Beloved Brontosaurus and Written in Stone. He also writes the National Geographic blog Laelaps

Personally I get tired of the way most fiction assumes that prehistoric life consisted exclusively of dinosaurs, mammoths, and sabertooth cats. I’d love to see more exploration of the creatures that existed before and after the age of dinosaurs. The various Walking With… specials from England did a nice job exploring those periods, and the first few seasons of the semi-spinoff series Primeval from the same producers did so as well (we didn’t see an actual dinosaur on that show until the start of season 2, though season 1 did feature pterosaurs and a mosasaur), but as the series went on, it became more and more about dinosaurs, mammoths, and such to the exclusion of less familiar beasts. And I can’t think of anything else in fiction that’s really dealt with non-dinosaurian creatures from, say, the Carboniferous or Permian or Tertiary or whatever — unless you count the various movies that used dimetrodons and mistook them for dinosaurs.