Roshar is a strange place to grow up, if you’re a species. There’s no convenient topsoil for plants to grow in, no predictable seasons to adapt to, and, perhaps most importantly of all, every few days there’s a continent-spanning hurricane to survive, strong enough to uproot trees, lift boulders, and toss them through the air, turning every pebble into potentially deadly shrapnel, all while dropping the temperature drastically and filling the sky with lightning. The planet is somewhat less than hospitable. Despite these conditions, life has found a way to carve out evolutionary niches, and the resulting ecology is incredible, alien and strange, while still presenting a kind of beauty. Join me as I explore the flora and fauna with which Brandon Sanderson has populated The Way of Kings.

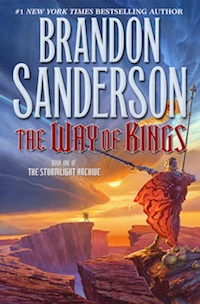

Flora

The vast majority of The Way of Kings is spent at the Shattered Plains, a barren, rocky tableau that is practically devoid of plant life. It’s easy to forget that, despite the highstorms, much of Roshar manages to support verdant environments, with a lot of biodiversity. Plants have adapted a number of strategies to survive the devastating highstorms.

Rapid Plant Movement

Most plants on earth (but not all) are characterized by immobility, but this is not the case in Roshar. After generations being uprooted by the wind many plants have learned to respond to nearby movement, and can now respond to nearby threats. Check out the clever grass:

Most plants on earth (but not all) are characterized by immobility, but this is not the case in Roshar. After generations being uprooted by the wind many plants have learned to respond to nearby movement, and can now respond to nearby threats. Check out the clever grass:

The wagons continued to roll, fields of green extending in all directions. The area around the rattling wagons was bare, however. When they approached, the grass pulled away, each individual stalk withdrawing into a pinprick hole in the stone. After the wagons moved on, the grass timidly poked back out and stretched its blades toward the air.

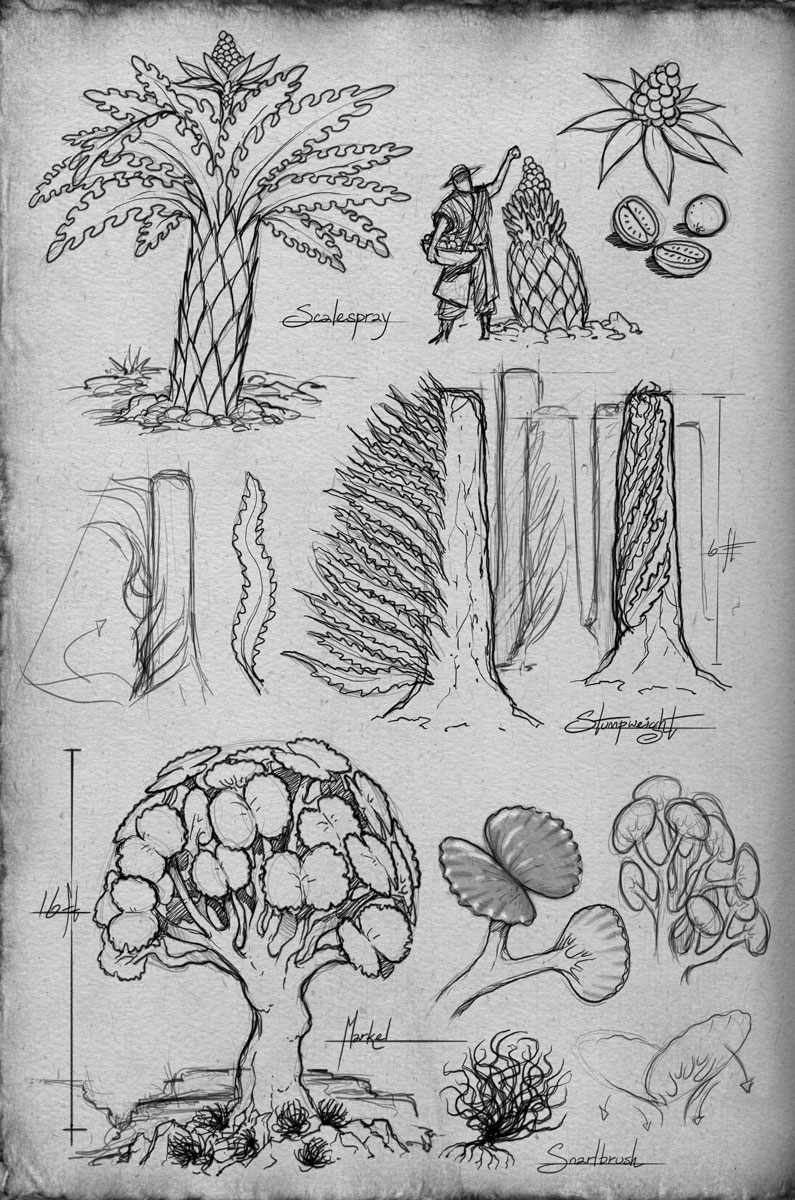

While the grass retracts entirely into the ground, most plants don’t go as far, opting to only pull in their most vulnerable structures, their leaves or needles, closing their petals, or twining their fronds around themselves. Shallan documented this behavior in scalespray, stumpweight, and markel in her sketchbook. And although most familiar real-world example of rapid plant movement is the Venus fly trap, which snaps closed to capture prey, but defensive RPM isn’t unheard of. Check out how the touch-me-not (Mimosa pudica) responds to being touched:

I can’t recall offhand any predatory plants in The Way of Kings, but who knows what ecological wonders Roshar has yet to reveal?

Rock-like Bark and Shells

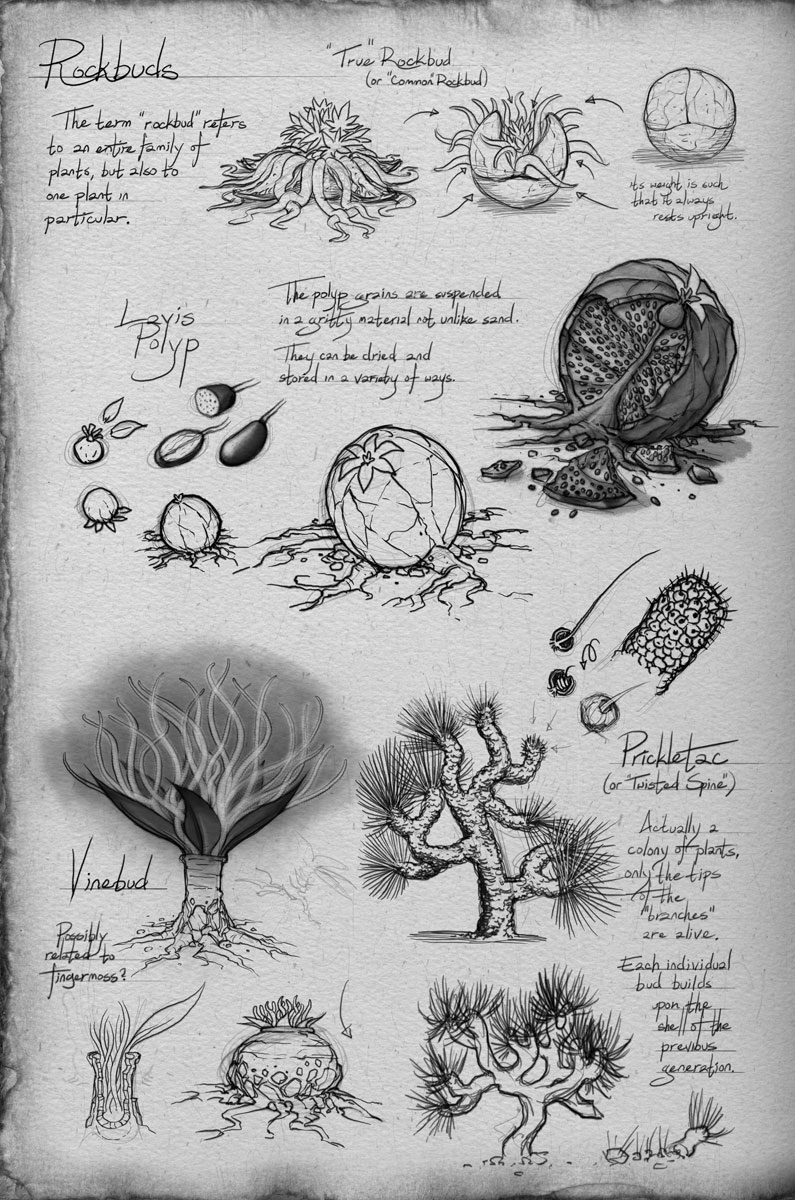

Retracting sensitive exterior parts would be relatively useless without some solid defensive structures to retreat into, and since only rock can weather the highstorms, plants have evolved to be as much like rocks as possible. Perhaps drawing on the calcium- and sediment-rich water left behind after highstorms, the trees have managed to make their bark as hard and thick as stone. Many shrubs are actually only alive at their tips. Other species exhibit coral-like organization. Prickletac, for example, is a colony plant made up of tiny barnacles that cling together, like coral polyps. (Special thanks to Ben McSweeney, the interior illustrator for The Way of Kings, for pointing out how prickletac works in the comments!)

Retracting sensitive exterior parts would be relatively useless without some solid defensive structures to retreat into, and since only rock can weather the highstorms, plants have evolved to be as much like rocks as possible. Perhaps drawing on the calcium- and sediment-rich water left behind after highstorms, the trees have managed to make their bark as hard and thick as stone. Many shrubs are actually only alive at their tips. Other species exhibit coral-like organization. Prickletac, for example, is a colony plant made up of tiny barnacles that cling together, like coral polyps. (Special thanks to Ben McSweeney, the interior illustrator for The Way of Kings, for pointing out how prickletac works in the comments!)

Farmers of Roshar use these shells to their advantage. Species of the rockbud family can be grown year-round, with farmers cultivating what looks to all the world like tiny boulders, before eventually breaking them open and revealing the rows and rows of hidden grains.

Feeding Behaviors

Although most plants spend a lot of their time imitating rocks, there is a specific moment when they open their shells wide to display the dizzying array of life on Roshar. That moment is directly following a highstorm:

The time right after a highstorm was when the land was most alive. Rockbud polyps split and sent out their vines. Other kinds of vine crept from crevices, licking up water. Leaves unfolded from shrubs and trees. Cremlings of all kinds slithered through puddles, enjoying the banquet. Insects buzzed into the air; larger crustaceans—crabs and leggers—left their hiding places. The very rocks seemed to come to life.

You see behavior like this on Earth as well. After a period of significant rainfall, deserts tend to experience rapid, short-lived blooming, with huge numbers of plants and animals surfacing to take in as much water as they can, before returning to their defensive positions or live-preserving periods of dormancy. In Roshar there is an added element of beauty to this moment; the flowering draws a huge quantity of lifespren.

But it’s not just after a highstorm that plants come alive and show their colors:

He poured some water on his hand from his own canteen and flung it at the brown snarlbrush. Wherever sprayed droplets fell, the brush grew instantly green, as if he were throwing paint. The brush wasn’t dead; it just dried out, waiting for the storms to come. Kal watched the patches of green slowly fade back to tan as the water was absorbed.

This goes along with what we know about feeding patterns, but does highlight something strange. Plants are green because of chlorophyll, a molecule that is crucial to photosynthesis. It seems that the chlorophyll in this snarlbrush is only activated when touched by water, which is a little weird considering that this plant will receive most of its water during a highstorm, when the sky will be dark as night. It seems like the snarlbrush’s chloroplasts nevertheless can’t function without the presence of water.

There’s an added element to explain the way plants flourish after a highstorm, an element which might also explain the mechanism by which they form their hard, protective shells.

Lirin had once explained that highstorm rains were rich with nutrients. Stormwardens in Kholinar and Vedenar had proven that plants given storm water did better than those given lake or river water. Why was it that scientists were so excited to discover facts that farmers had known for generations and generations?

Stormwater is later described as tasting “metallic.” It carries “crem,” a sediment that builds up on buildings into stalactites, which have to be scraped regularly. It seems that highstorms, in their sweep across Roshar, pick up the outer layers of rock, carrying those materials along with them, and the sediment is absorbed into plants when they drink stormwater. The plants have adapted to incorporate the rocky sediment into their bark.

Fauna

The animals that populate the environs of Roshar are just as thoroughly adapted to the highstorms than the plants. Mammals and birds, with their weak, fleshy exteriors, are almost unheard of, with shells and carapaces replacing skin and fur. Even some hominids have taken on crustacean elements. Despite this, the evolutionary niches we see on earth are filled, and many animals exist in rough analogies to familiar relationships with humankind.

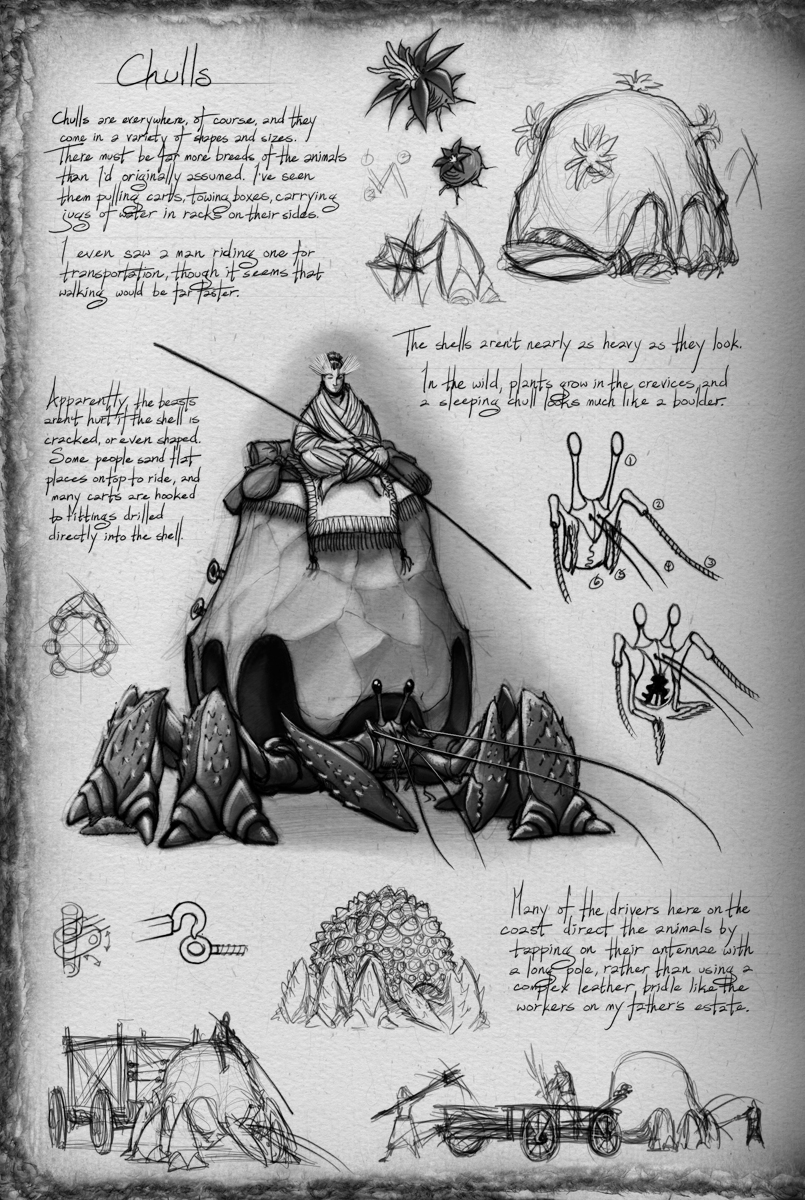

Domesticated Beasts

Even in a world like Roshar, where farmers harvest rocks and travel is constantly disrupted by hypercanes, humans need something to pull their farm equipment and caravans. Meet the chulls: huge, domesticated crabs with boulder-like shells. Chulls are docile, tame after generations of breeding, and immensely useful for all kinds of tasks. In disposition they resemble nothing so much as cattle, and fill many of the same purposes. Chulls pull wagons and help farmers. Dalinar even uses chulls to pull his rolling bridges on the Shattered Plains, although they’re far too slow to compete with the other highprinces’ less humane methods. During highstorms or when sleeping the chulls simply retract their legs into their shells, becoming almost identical to boulders. Unless, of course, their shells have been painted or sanded into different shapes, neither of which augmentations the creatures seem to mind at all.

Even in a world like Roshar, where farmers harvest rocks and travel is constantly disrupted by hypercanes, humans need something to pull their farm equipment and caravans. Meet the chulls: huge, domesticated crabs with boulder-like shells. Chulls are docile, tame after generations of breeding, and immensely useful for all kinds of tasks. In disposition they resemble nothing so much as cattle, and fill many of the same purposes. Chulls pull wagons and help farmers. Dalinar even uses chulls to pull his rolling bridges on the Shattered Plains, although they’re far too slow to compete with the other highprinces’ less humane methods. During highstorms or when sleeping the chulls simply retract their legs into their shells, becoming almost identical to boulders. Unless, of course, their shells have been painted or sanded into different shapes, neither of which augmentations the creatures seem to mind at all.

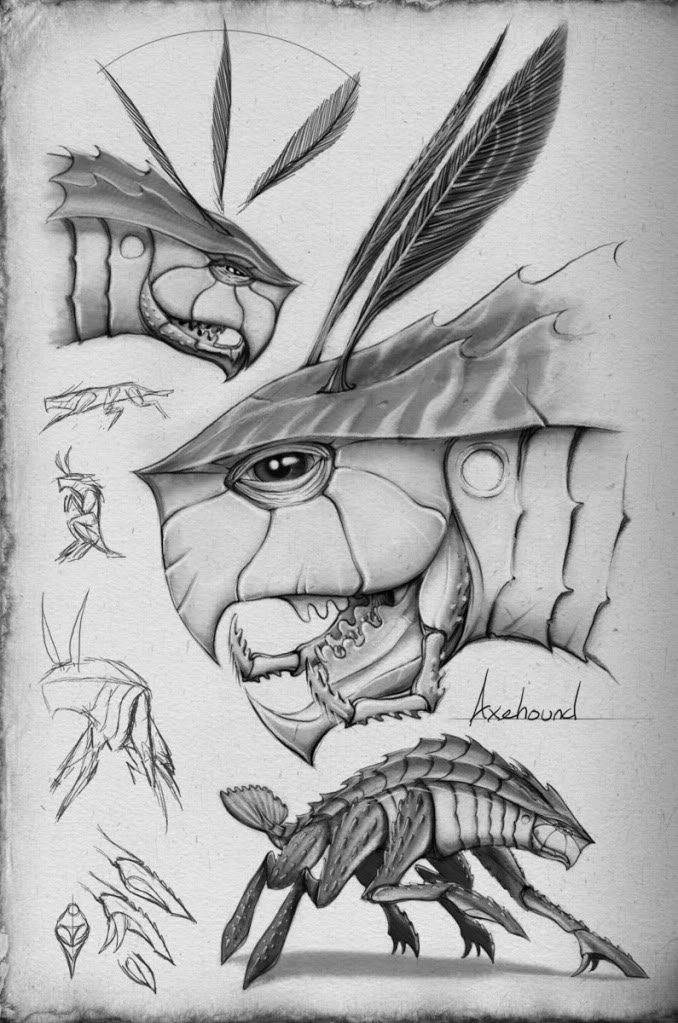

Even stranger, in my opinion, than chulls are the Rosharan analogue to dogs. The axehound is a hexapedal semi-crustacean that lighteyes keep for companionship or to help them in hunts. Their carapace is a strange blend of skin and shell, and their trumpet-like calls are multi-voiced, demonstrating that axehounds have developed multiple sets of vocal chords. Visually, axehounds remind me of some terrifying blend of lobster and dog, with perhaps a little bit of cave cockroach thrown in, but I guess humans will find their animal companionship wherever they can.

Even stranger, in my opinion, than chulls are the Rosharan analogue to dogs. The axehound is a hexapedal semi-crustacean that lighteyes keep for companionship or to help them in hunts. Their carapace is a strange blend of skin and shell, and their trumpet-like calls are multi-voiced, demonstrating that axehounds have developed multiple sets of vocal chords. Visually, axehounds remind me of some terrifying blend of lobster and dog, with perhaps a little bit of cave cockroach thrown in, but I guess humans will find their animal companionship wherever they can.

Creatures of the Wild

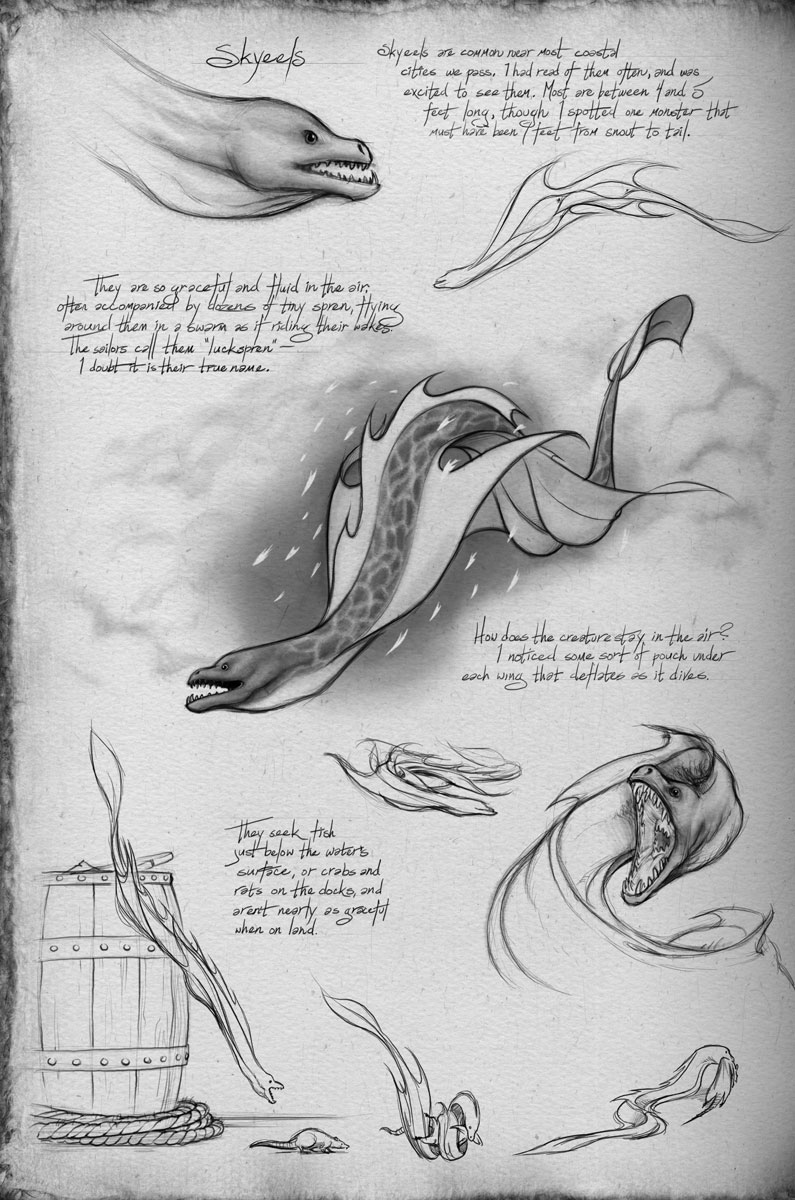

Not all of the creatures of Roshar can be tamed. There are predators out there, like the skyeel, a kind of flying eel or snake that pounces on small crabs and devours them. Skyeels can also swim, and most likely shelter beneath the surface of the ocean during storms. Humans must also contend with whitespines, a horse-sized blend of reptile and carapace, with long white tusks and vicious claws. Lighteyes hunt whitespines much as medieval Europeans hunted boars, and the sport is no less dangerous.

Not all of the creatures of Roshar can be tamed. There are predators out there, like the skyeel, a kind of flying eel or snake that pounces on small crabs and devours them. Skyeels can also swim, and most likely shelter beneath the surface of the ocean during storms. Humans must also contend with whitespines, a horse-sized blend of reptile and carapace, with long white tusks and vicious claws. Lighteyes hunt whitespines much as medieval Europeans hunted boars, and the sport is no less dangerous.

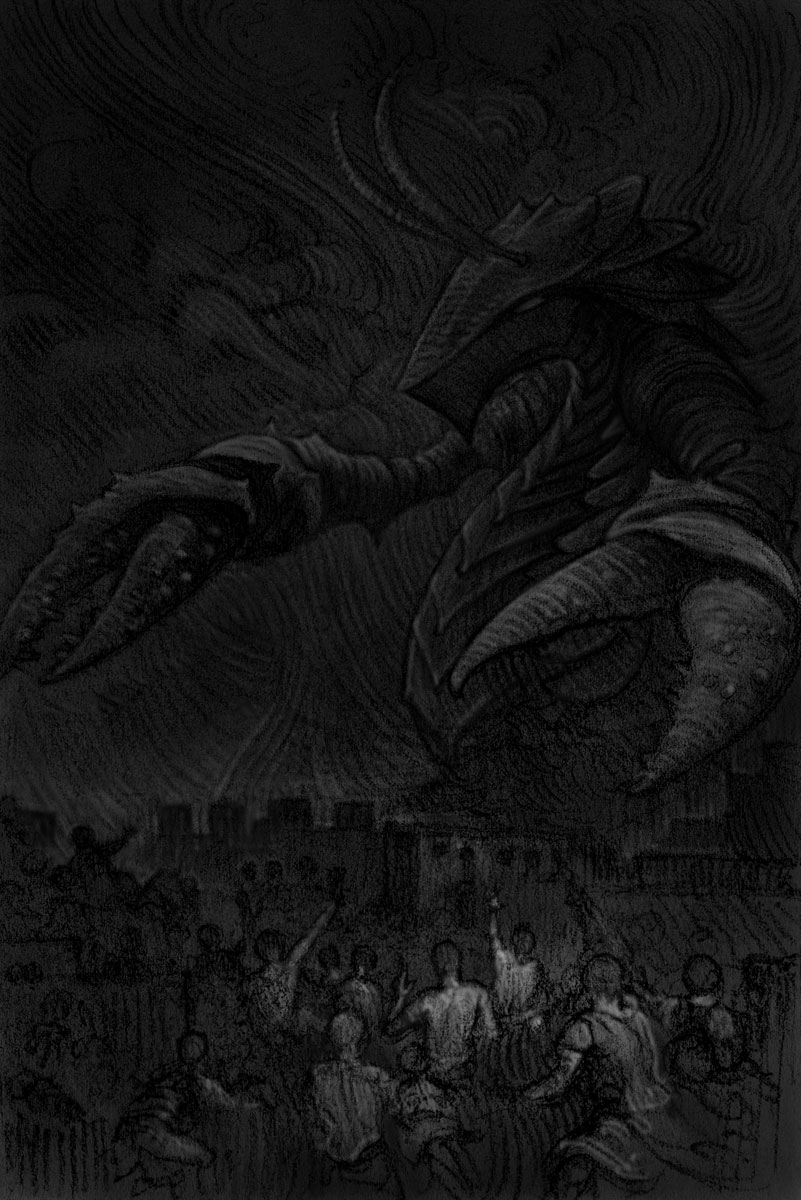

The most important wild creatures in the Stormlight Archive, however, are the greatshells. Variations of these massive shelled creatures occupy many different environments. The chasmfiends of the Shattered Plains can grow as large as thirty feet tall, have massive claws, an incredibly thick, stone-like carapace, and mouths full of barbed mandibles. These creatures have changed the shape of the war between the Parshendi and the Alethi because of one incredibly peculiar quirk of their biology: the gemheart.

At the center of every greatshell is a massive, uncut gemstone called a gemheart. As gems are not only the primary currency of Roshar, but also the source of magical potency, greatshells are the most important game in the world. But how in Damnation does a creature have a gemstone for a heart? Well, it’s possible that greatshells work somewhat like clams, layering sediments over irritants over the course of years, but that isn’t really very much like the way most gemstones are formed. The interior of greatshells would also have to exert huge amounts of heat and pressure on the rock particles they absorb, considering that many of the beasts have gemhearts of diamond.

At the center of every greatshell is a massive, uncut gemstone called a gemheart. As gems are not only the primary currency of Roshar, but also the source of magical potency, greatshells are the most important game in the world. But how in Damnation does a creature have a gemstone for a heart? Well, it’s possible that greatshells work somewhat like clams, layering sediments over irritants over the course of years, but that isn’t really very much like the way most gemstones are formed. The interior of greatshells would also have to exert huge amounts of heat and pressure on the rock particles they absorb, considering that many of the beasts have gemhearts of diamond.

It is not, by the way, at all clear whether the gemhearts actually function analogously to hearts. Alethi scholarship on dead chasmfiends is almost nonexistent. It could easily be the case that the gems have no biological purpose. It could also be the case that the gemhearts sustain the chasmfiends with their ability to store stormlight. More fieldwork is required on the subject.

There are many more mysteries about how greatshells live. Their blood is violet, and stinks of mold, which despite myself I can’t think of an explanation for. Beyond that, they are far larger than any crustacean should be able to grow. During a Q&A Brandon Sanderson said that this is possible for a couple of reasons. First, gravity is lower on Roshar. More importantly, however, greatshells have a symbiotic relationship of some sort with a special kind of spren.

Chasmfiends aren’t the only kind of greatshell. On the coast of Iri there are aquatic greatshells, and in his YouTube previews for Words of Radiance Sanderson revealed that many of the Reshi Isles are not actually islands. That’s right, there are greatshells out there as big as islands.

Shinovar

There is an exception to every ecological rule on this planet, and all of these are present in the isolated nation of Shinovar. In the far west of the continent, separated from the rest of the world by a high mountain range, there is a pocket ecosystem that has evolved without the influence of the highstorms. Here there is soil. There is grass that does not move. And there are also the strangest animals of all; horses, chickens, and pigs. Yes, that’s right: the classic fauna of European earth is alive and well in Roshar. These animals are incredibly rare, incredibly valuable, and incredibly out of place. What are chickens doing on the crab planet? Why have horses evolved in the same world as lobster-dogs?

These are questions we’re not yet equipped to answer. Shinovar is a mystery in the Stormlight Archive so far, but one that is sure to be explained in time. In the meantime, there is another article to be written on this subject, one that explores how humans fit into this harsh environment, how they are contrasted with the Parshendi, and whether, in an alien world, humans are actually the most out-of-place species.

Carl Engle-Laird is the fiction assistant for Tor.com. He is one of the Way of Kings rereaders and Tor.com’s resident Stormlight Archive correspondent. He has been speculating about axehound GIFs all day. You can follow him on Twitter.