There are many possible reasons why I’ll choose certain books for review. Most often it’s simply because they look promising. Occasionally it’s because I’m a fan of the author, series, or (sub-)genre. Sometimes I just get drawn in by something intriguing or odd in the publicity copy.

But every once in awhile there’s a book that, I feel, just deserves more attention, a book that’s not getting read enough for some reason. In those cases, it’s wonderful that I can take advantage of the generous platform Tor.com gives me to introduce people to what I consider hidden gems.

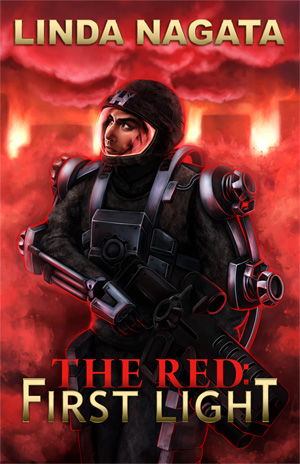

Case in point, Linda Nagata’s excellent, independently-published military SF novel The Red: First Light, which, if I can just skip to the point for people who don’t like to read longer reviews, you should go ahead and grab right now, especially if you’re into intelligent, cynical military SF. If you want more detail, read on.

I remembered Linda Nagata from her successful Nanotech Succession novels in the 1990s: Tech Heaven, The Bohr Maker, Deception Well and Vast. Back in those days when I still made more impulse book purchases in physical bookstores, the neon framing around those Bruce Jensen covers was so effective that I picked them up almost involuntarily. I lost track of the author for a while after these (and she published a bunch of stuff I need to catch up on since then) but when I saw a mention of The Red: First Light, her newest SF novel, published by her own Mythic Island Press, I decided to give it a shot—and I’m ever so glad I did.

The tone of the novel is set right from the very first paragraph:

“There needs to be a war going on somewhere, Sergeant Vasquez. It’s a fact of life. Without a conflict of decent size, too many international defense contractors will find themselves out of business. So if no natural war is looming, you can count on the DCs to get together to invent one.”

The speaker is Lt. James Shelley, a highly cynical but competent officer who leads a high-tech squad of exoskeleton-enhanced, cyber-linked soldiers in the latest manufactured international incident, deep in the Sahel. (The location illustrates another one of Shelley’s axioms: “Rule One: Don’t kill off your taxpayers. War is what you inflict on other people.”)

The start of The Red: First Light is simply flawless. Shelley introduces a new member to the squad, and in just a few scenes, you know everything you need to know: the tight bond between the soldiers, their faith in the highly cynical but reliable Shelley, the Linked Combat Squad technology, the general situation. The exposition is perfectly delivered, and before you know it you’re in the thick of it.

“The thick of it” in this case means a series of intense, well-written scenes describing life and combat in a remote military outpost somewhere in Sub-Saharan Africa: patrols, combat incidents, friendly interactions with the locals who are, in most cases, as war-weary as the soldiers. There’s an inexorable pull to this part of the novel: the soldiers live in a round-the-clock state of combat readiness, interrupted by brief chunks of drug-induced sleep. They’re monitored 24/7. There are no breaks. Once you’re into this book, it’s hard to put it down until you reach the shocking end of the first section.

It’s also full of examples of the plight of the common soldier, created by the faceless, immensely rich defense contractors who manipulate world politics to keep conflicts (and sales) going. High-tech combat equipment is recovered after a soldier’s death because it’s cheaper to train another grunt than build another robot. Lt. Shelley has his dad send medications for the squad’s dogs, and buys their food from the locals on his own dime. It reminded me of the saddening reality of teachers having to spend their own money on basic school supplies.

There are many more powerful illustrations of this “only a pawn in their game” theme (although a more appropriate Dylan tune to refer to here would probably be “Masters of War”). Drones relay the commands of faceless, codenamed Guidance officers down to the field. Most disturbingly, skullcaps worn by soldiers like Shelley allow their emotional and mental state to be monitored and altered as needed. Shelley is frequently aware that his true feelings are suppressed, and have been suppressed for such a long time that he’s become dependent. At one point, he notes drily:

The handbook says the brain stimulation [the skullcap] provides is non-addictive, but I think the handbook needs to be revised.

This emo-monitoring ends up highlighting the real issues: identity and awareness. Shelley occasionally has inexplicable, but always accurate premonitions. Where do they come from? Is it the voice of God, as one of his squadmates insist? Or is there something else going on? And regardless, how much of a person’s original identity remains if they are monitored and controlled 24/7?

Somewhere deep down in my mind I’m aware of a tremor of panic, but the skullnet bricks it up. I watch its glowing icon while imagining my real self down at the bottom of a black pit, trapped in a little, lightless room, and screaming like any other soul confined in Hell.

If my real self is locked away, what does that make me?

I know the answer. I’m a body-snatching emo-junkie so well-managed by my skullnet that the screams of my own damned soul are easy to ignore. But there is someone out there who can get inside my head. Am I haunted by a hacker? Or is it God?

Once the first “episode” of the novel is over, these become central questions. While that opening section is one long, intense, adrenaline-fueled rush, it focuses on what’s ultimately just a small part of the conflict. In section two, the novel takes a sharp turn when it starts exploring the broader issues. That also means things slow down considerably, for a while at least. Not that this is a bad thing—there’s a depiction of wounded soldiers’ rehabilitation that’s incredibly poignant, for one—but the change in pace is noticeably abrupt. Eventually, all of the pieces of the puzzle come together in a spectacular conflict that also sets up future installments.

Now, is The Red: First Light perfect? Well, no. As mentioned before, the novel abruptly loses some of its tension and pace when the scope of the story broadens in the second episode. There’s one character (Elliott) who keeps turning up in situations I found highly improbable. In fact, the whole “reality show” idea struck me as improbable too. And in the third section, the final showdown felt, well, just a little silly in a B-movie sort of way. I’m staying intentionally vague here to avoid major spoilers because, again, you must read this novel. Plus, there are also very many spectacular, memorable scenes in the second half of this novel that I’d love to talk about here. Very, very many.

Maybe most importantly, and in case it wasn’t clear yet, this novel wears its politics rather obviously on its sleeve. There’s nothing wrong with that, especially if you agree with some of the points the author implies—which I happen to, strongly—but I expect that there’s a good chunk of the public, including many people who habitually read military SF, who may take issue with some of the novel’s underlying ideas even as they cheer for its characters.

However, I want to emphasize again: this is an amazing novel, and if you’re into military SF at all, you really have to check it out. If you enjoyed the way an author like Myke Cole updated military fiction tropes (in his case in a contemporary fantasy setting), you definitely should grab a copy. The Red: First Light is a dark, intelligent, cynical take on military SF. It’s an excellent novel that deserves a much larger audience.

The Red: First Light is available now from Mythic Island Press

Read an excerpt from the novel here on Tor.com!

Stefan Raets reads and reviews science fiction and fantasy whenever he isn’t distracted by less important things like eating and sleeping. You can find him on Twitter, and his website is Far Beyond Reality.

Oh boy, do I hate that trope. It is so smugly self-righteous, so beyond any need to provide any evidence. And the people who believe it so often seem to think that these corrupt, easily lead governments are a force for good in the world. If they were all libertarians at least they would be consistant in their beliefs.

Shaun Duke and I were lucky enough to talk to Linda about the book on the Skiffy and Fanty Podcast. We liked it a lot, too.

So nice to see this getting some attention – it’s a really interesting story, cleverly written and the narrative voice is brilliantly involving (also Shelley is just an awesome character in general). I wasn’t sure it was my kind of thing until I started reading, but as mentioned, that opening section sucks you in and doesn’t let up for a second. Definitely worth giving it a shot.

There’s also a prequel short story Through Your Eyes (basically Shelley’s origin story) available to buy through the Mythic Island Press site here and one of her shorts available on the Lightspeed site here (Nightside on Callisto), is a far-future sequel (written previously though) featuring one of the supporting characters from First Light (spoilers for First Light with that one, obviously).

@Ad : regardless of the accuracy of the statement as related to reality and the world we live in, that “trope” is part of the setting the author puts us in. Just like on Good Old Barsoom there was breathable air for John Carter, Defense Contractors DO manufacture wars in The Red : First Light.

From that point on, no need of proof/evidence, suspension of disbelief should apply.If it doesn’t work for you, too bad.