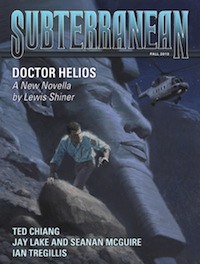

Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a space for conversation about recent and not-so-recent short stories. While we’ve been discussing quite a lot of anthologies, recently, the periodicals have continued publishing great work—and this week, I can’t resist talking about a story that has been attracting plenty of well-deserved attention: “The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling,” by Ted Chiang, published in the Fall 2013 issue of Subterranean Magazine.

Chiang, winner of multiple Nebula Awards (as well as Hugo Awards, Locus Awards, and a fistful of other accolades), is not a remarkably prolific writer—so, it’s always a delight to see a new piece of work from him. The fact that this novelette is free to read online is doubly nice. And, triply-nice, it’s also very good.

“The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling” is a compelling exploration of issues of language, literacies, and subjectivity through a science fictional (as well as a historical) lens. It’s also a story that feels very much in Chiang’s wheelhouse: it is slow moving, contemplative, and deeply enmeshed with issues of technology and current research. It extrapolates, explains, and leaves the reader to suss out the various complications and implications that are woven throughout the two narratives—each, on their own, rather straightforward and deceptively simple.

The first narrative is told by an older journalist: he is sharing with the reader his experience with, concerns about, and research on a new technology, “Remem.” This technology is designed to allow people to continually and easily access their lifelogs—video recording of their daily lives taken in as much or as little quantity as they prefer—and is a form of artificial memory. The second narrative is set in Africa: it is about a young man, Jijingi, who is taught writing by a missionary, and his struggles to synthesize his oral culture with written literacy. The protagonist, we find at the end, has fictionalized the story of Jijingi to reveal a truth via the use of narrative—to make a point about the complex nature of “truth” and literacy, story and technology.

Neither narrative offers easy answers to the questions posed by increases in technological innovation, particularly in terms of memory and subjectivity. “The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling” offers, in the end, more of realistic conclusion: that literacies have their consequences and their benefits, and that cultural mores often have much to do with our beliefs on that score. The richness of this piece is not in its potential for didacticism, but in its bringing to life the experience of technological interventions in individual lives, in terms of their respective overlapping literacies.

In that sense it is very much a character-driven piece, more about personal lives than “ideas.” The narrator’s voice is undemanding and unassuming; he is simply speaking to us, telling us how he feels and why, for much of the story. Similarly, Jijingi’s life and relationships are rendered in sparse but close, revealing detail. These are inviting tactics that put the reader at ease with their place as intimate audience to the stories in question. When the narrator then begins to explore his own memories and finds, shatteringly, that he has been lying to himself for years about his parenting, this comes full circle: the reader, too, is experiencing the complications of the Remem literacy.

It is, after all, a literacy of the memory—a literacy one step further removed from the print literacy that complicates though also enriches Jijingi’s life. There is a thread in the story of the difference between the practical, exact truth and the emotional, functional truth, particularly in Jijingi’s narrative. This—as the title implies—is key: the idea that perhaps the exact truth is useful and vital, but also that the emotional truth should not be disregarded. (An aside: I also appreciate that this story does not disregard the wealth and value of oral culture.)

Also, as someone who works in academia—particularly, who has worked within rhetoric and pedagogy—and as a writer, this story struck me intensely. The prose is handsome, of course. But, more than just that, Chiang’s refusal to offer reducible answers to these broad questions about the effect of evolving literacies was a delight. Literacies are slippery and not without ethical and social consequence; literacies are also, as this story points out succinctly, intimately tied to technologies from paper to future digital memory-assistance. Though plenty of stories like to talk about story-telling and the ways in which narrative shapes life, fewer tackle the questions about literacy itself as a technology and a mechanism of societies. So, naturally, I appreciated having a chance to immerse myself in a story that did just that.

The work the story does with memory, too, is fascinating: how we lie to ourselves and others, how fallible memory has its functions and pitfalls—and how an “infallible” assisted memory would have different but very real function and pitfalls. There is an intriguingly wobbly sense of identity/subjectivity that comes out of the protagonist’s struggles with Remem and Jijingi’s struggles with written records that contradict the manner of truth his culture also values. Wobbly in the sense that it is not concrete—as we are, really, never concrete. We are fluctuating, and so are the characters in this story, based on their memories, the stories they know and tell, and their literacies.

“The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling,“ as with many of Chiang’s stories, is an elegant, technical piece that would not, in other hands, shine. I highly recommend giving it a read, and settling in to do so slowly—to savor it and not rush the development of the twinned narratives. I suspect I’ll be going back to reread it soon enough, too. There’s plenty to work through in the piece that I haven’t touched on enough here, from the father-daughter conflict to the larger thematic questions it raises about subjectivity. Overall, I’m glad to have had the opportunity to read it.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.