Summer of Sleaze is 2014’s turbo-charged trash safari where Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction and Grady Hendrix of The Great Stephen King Reread plunge into the bowels of vintage paperback horror fiction, unearthing treasures and trauma in equal measure.

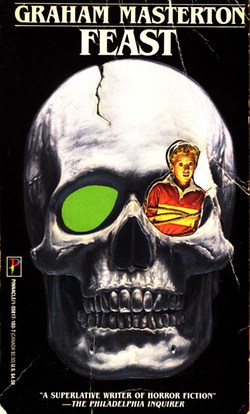

So far this year I’ve read the powerful Thank You For Your Service, David Finkel’s look at the shattered lives of servicemen returning home from Iraq. I’ve read Donna Tart’s The Goldfinch, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. I’ve read Austin Grossman’s deceptively experimental You that transmutes the lead of early computer gaming into the gold of transcendence. I’ve read Allie Brosh’s so-personal-it-hurts Hyperbole and a Half, Neil Gaiman’s emotional and revealing The Ocean At the End of the Lane, and two new books by Stephen King, one of America’s greatest storytellers. None of them—none of them—has provided me as many moments of pure joy as a little mass market paperback from 1988 called Feast by Graham Masterton. John Waters once said, “Good taste is the enemy of art.” If that’s true, and I believe it is, then Feast is the Mona Lisa.

Starting as a local newspaper reporter when he was 17, Scotsman Graham Masterton edited Mayfair, the men’s magazine, before moving on to Penthouse. At the tender age of 25 he wrote the sex instruction book, Acts of Love, and has since gone on to author close to 30 more sex manuals, including How To Drive Your Man Wild in Bed (2 million copies sold). In 1975 he took a break from instructing couples in the gentle art of nookie to write The Manitou, a horror novel that Will Errickson will cover here in more detail later this summer.

The Manitou launched his fiction career and Masterton went on to write over 70 books, mostly horror novels and sex guides, but also historical sagas, humor collections, and movie novelizations. When asked what he’s working on he names ten projects, ranging from sex books, to thrillers, to horror novels, to short stories. Asked which of his books he would recommend for a new reader, he names eight, then two he has reservations about, then throws in another couple of titles for good measure. For Graham Masterton, too much is never enough.

It’s this belief in overkill that causes critics to file their reviews of Masterton’s books in a sort of stunned, slack-jawed daze. “Though Masterton’s plot moves well and is action-oriented,” a still-reeling reviewer for Kirkus writes in 2013, “the condoning of generally abnormal human interactions by all hands may make readers wonder what, in this world, normal is.” Another hapless Kirkus reviewer in 1992 reviewed Masterton’s Master of Lies, “Be warned: Masterton’s newest, about the ritualistic resurrection of the fallen angel Beli Ya’al in San Francisco, opens with what may be the single most sadistic scene in horror history…the excruciating detail here seemingly acknowledges no bounds and culminates in a soul-draining depiction of a giant mutilating the penis of a renowned psychic.”

But Masterton isn’t looking to shock. He’s merely obeying his one commandment, “Be totally original. Don’t write about things that have been written about a million times before, like vampires or zombies or werewolves. Invent your own threats.” And so he writes about demonic tank drivers, killer chairs, Native American spirits out for revenge on the white man, Japanese spirits out for revenge on the white man, the Fog City Satan, genetically engineered killer pigs, crop blights, water shortages, and, in the case of Feast, gourmet religious cults.

Published in 1988, Feast opens with the immortal line from its main character, Charlie, “Well, then, how long do you think this baby has been dead?” Turns out that the “baby” in question is a schnitzel served at the Iron Kettle, a crummy joint in upstate New York that Charlie is reviewing for Maria (Motor Courts, Apartments, Restaurants, and Inns of America) a food and lodging guide for traveling salesmen. He’s a few days into a three-week trip with his teenaged son, Martin and while the trip was ostensibly designed so that they can spend time together, it turns out that Charlie is a lousy dad no matter what. Selfish, oblivious to others, and prone to screwing things up, he’s more interested in reviewing the next boarding house than bonding with his son.

By chapter 4, he’s obsessed with Le Reposoir, an exclusive French dining club in the middle of nowhere, that refuses to let him book a table and, consequently, drives him bananas. After picking up a floozy at his hotel and spending a dirty night in her room (Masterton hails from the Eyes Wide Open school of sex scenes), he returns to his room to find that Martin is missing. Most books hoard their plot twists, clutching them close to their chests, but Masterton has more twists up his sleeve than the average bear and it’s no spoiler to reveal that Le Reposoir turns out to be a front for a cult of cannibals named the Celestines, and that Martin is in their clutches. It’s also not a spoiler to reveal the first big wrinkle: the Celestines regard being eaten as the holiest of acts and Martin has joined them of his own free will because he wants to be eaten as a peak religious experience. Compared to his dad’s grubby, pointless life, participating in a transcendental auto-cannibalism orgy actually doesn’t sound that bad, and throughout the book the Celestines maintain the moral high ground.

Wherever you think this book won’t go, Masterton not only goes there, he reports back in lunacy-inducing detail. By the time the last page is turned there have been amputee dwarf assassins, lots of sex, flaming dogs, one of the most harrowing scenes of self-cannibalism I’ve ever read, lots of betrayal, at least one over-the-top conspiracy theory, at least one death by explosive vomiting, and an actual appearance by Jesus Christ. That’s right—Feast goes so far over the top that it requires a last minute intervention by the Son of God himself in order to wrap things up.

Throughout, Masterton enjoys himself immensely and it’s impossible to read Feast and not do the same. Masterton cares about his characters, and while his women may fall for the hero a bit too quickly, they are usually well-rounded and pursuing agendas of their own. His dialogue is funnier than it needs to be, his gore is gorier, and his sex is more explicit. If you’d prefer something more towards the middle of the road there’s always Dean Koontz. Masterton’s books may not be the most tasteful, they may not be the most consistent, but you get the impression that he’ll gladly hang up his hat and call it a day the minute they’re not the most original.

Grady Hendrix is the author of Satan Loves You, Occupy Space, and he’s the co-author of Dirt Candy: A Cookbook, the first graphic novel cookbook. He’s written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today and his story, “Mofongo Knows” appears in the anthology, The Mad Scientist’s Guide to World Domination.