Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

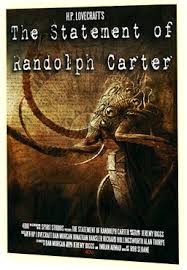

Today we’re looking at “The Statement of Randolph Carter,” written in December 1919 and first published in the May 1920 issue of The Vagrant. You can read the story here. Spoilers ahead.

“Over the valley’s rim a wan, waning crescent moon peered through the noisome vapours that seemed to emanate from unheard-of catacombs, and by its feeble, wavering beams I could distinguish a repellent array of antique slabs, urns, cenotaphs, and mausolean facades; all crumbling, moss-grown, and moisture-stained, and partly concealed by the gross luxuriance of the unhealthy vegetation.”

Summary: Randolph Carter is giving a formal statement about the disappearance of his friend Harley Warren. He has told law enforcement officials everything he can remember about the night Warren went missing—in fact, he’s told them everything several times. They can imprison or even execute him if they think that will serve “justice,” but he can do no more than repeat himself and hope that Warren has found “peaceful oblivion,” if there is such a thing.

Warren was a student of the weird, with a vast collection of rare books on forbidden subjects, many in Arabic. Carter took a subordinate’s part in Warren’s studies, the exact nature of which he’s now mercifully forgotten. They were terrible, though, and Warren sometimes scared Carter, most recently on the night before his disappearance, when he went on and on about his theory of why “certain corpses never decay, but rest firm and fat in their tombs for a thousand years.”

A witness has testified to seeing Warren and Carter on the Gainesville Pike, headed for Big Cypress Swamp. Carter doesn’t quite recall this, but doesn’t deny it. He can second the witness about what they were carrying: spades, electric lanterns, and a portable telephonic apparatus. Warren also carried a book he’d received from India a month before, one in a script Carter doesn’t recognize. Just saying. Oh, and another thing Carter’s sure about is their final destination that fatal night: an ancient cemetery in a deep, damp, overgrown hollow. This terrible necropolis is setting to the one scene he can’t forget.

Warren finds a half-obliterated sepulchre, which he and Carter clear of drifted earth and invasive vegetation. They uncover three flat slabs, one of which they pry up. Miasmal gases drive them back. When these clear, they see stone steps leading down into the earth.

Warren will descend alone, for he says that with Carter’s frail nerves, he couldn’t survive what must be seen and done below. Really, Carter couldn’t even imagine what the “thing” is like! However, Warren has made sure the wire connecting their telephone receivers is long enough to reach the center of the earth, and so they can stay in touch during his solo adventure.

Down Warren goes, while Carter gets to fidget alone on the surface, imagining processions of amorphous shadows not cast by the waning crescent moon and such like. A quarter hour later, Carter’s phone clicks, and Warren speaks in quivering accents quite unlike himself. What he’s found is unbelievably monstrous, but he can’t tell the frantic Carter any more than that, for no man could know it and live!

Unfortunately, that seems to include Warren. He begins to exhort Carter to put back the slab and run—“beat it” being the boyish slang to which he’s driven in his extremity. Carter shouts back that he won’t desert Warren, that he’s coming down after him. Warren continues to beg him to flee, voice growing fainter, then rising to a last shriek of “Curse these hellish things—legions—My God! Beat it! Beat it! Beat it!”

Silence follows. Carter does not go down the steps. Instead he sits variously muttering, shouting and screaming into his receiver: Is Warren there?

Eventually he hears the thing that drives him mindless to the edge of the swamp, where he’s found the next morning. It is a voice, hollow, remote, gelatinous, inhuman, perhaps even disembodied. It isn’t Warren’s voice, in other words, but one that intones:

“YOU FOOL, WARREN IS DEAD.”

What’s Cyclopean: Sometimes the only way to describe the indescribable is with a lot of adjectives, and “deep; hollow; gelatinous; remote; unearthly; inhuman; disembodied” is quite the list. We also get the delightfully precise “necrophagic shadows.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Pretty limited degeneracy here. There’s the continued suggestion that a large proportion of nasty occult books are written in Arabic—but then, a lot of classic texts on everything are written in Arabic (and we get a lot of Latin too, though not here). Then there’s the suggestion that a book in an unknown alphabet is probably particularly suspicious. While that’s clearly the case here—dude, there are a lot of alphabets, and it isn’t weird that you don’t recognize them all.

Mythos Making: Randolph Carter is a major recurring character in Mythos and Dreamlands stories. Although we don’t see him at his best here, he’s a Miskatonic alumnus and will eventually quest in unknown Kadath.

Libronomicon: The fateful mission is precipitated by a book that Harley Warren has taken to carrying around in his pocket. Kind of like those little bibles with the green covers, but different.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Warren assures Carter that he’s too frail to sanely face the “fiendish work” that will be necessary beneath the earth. Seems a bit rude, frankly. And then, of course, he turns out to be a bit frail himself.

Anne’s Commentary

For the third time in four weeks of blog posts, one of Lovecraft’s friends gets fictionally messed up—Harley Warren’s counterpart in the dream that inspired “Statement” was Samuel Loveman. Lovecraft seems to have dreamt about Loveman a lot, because he also played a prominent part in the dream that led to “Nyarlathotep.”

Right up front let me say that I find more strikes in “Statement” than hits. Framing the story as a legal statement negates what could have been another successful retelling or recasting of dream (as “Nyarlathotep” is and “The Outsider” seems to be.) A statement must lay out the facts, no prose-poetics welcome. Here too many facts remain vague, unremembered, while others firmly stated seem incredible.

The setting is apparently Florida’s Big Cypress Swamp, now a national preserve. Located just north of the Everglades, it’s nowhere near Gainesville, don’t know about a Gainesville “pike.” When the officials tell Carter that nothing like the graveyard he describes exists in or near the Swamp, believe them. This “necropolis” sounds too old and too European in its accouterments. What’s more, the water table in Florida (especially in a swamp) is way too close to the surface to allow for those steps leading down and down and down, dampish but not submerged. Plus where are the gators? Got to have gators in South Florida, come on!

To be fair, Lovecraft knows his graveyard is not really part of any Florida swamp-scape. It’s in some kind of parallel Florida? In part of the Dreamlands impinging on Florida? The latter conceit would be more effective in a story that isn’t masquerading as a legal statement, hence prejudicing our expectations toward the factual.

The list of Lovecraft narrators rendered unreliable by possible madness or actual memory loss is a long one. Here the narrator is just too unreliable. Yeah, maybe his statement is based on hallucination or nightmare. For sure, his memory is riddled with odd holes and implausible blank stretches—odd and implausible because when he does remember something (the graveyard episode), he remembers it down to the dialogue, with all the words and all tonal nuances intact. Kind of the way Wilmarth remembers Akeley’s lost letters? But I’m calling Lovecraft on this story, and I’m saying that Carter’s memory is entirely in the service of his creator’s decision to keep the central horror a mystery, as it doubtless was in the inciting dream. Our one clue to what’s under the slab is Warren’s theory about corpses that rest firm and fat in their tombs. This reminds me of “The Festival.” I’ll bet that among Warren’s rare Arabic books is the Necronomicon, and that he’s familiar with Alhazred’s contention that the bodies of sorcerers instruct the very worms that gnaw, causing them to “wax crafty to vex [the earth] and swell monstrous to plague it.” So, is it some of these wizards-turned-grubs (or grubs-turned-wizards) that Warren’s looking for—legions of them, all walking when they should crawl? That could account for the gelatinous nature of the voice that speaks to Carter!

That’s all speculation, though, and the reader would have to know “The Festival” in order for this maybe-connection to make “Statement’s” monsters more particular. Besides which, “The Festival” comes four years after this story, and Alhazred is two years away (first appearing in “The Nameless City”), and the Necronomicon itself is three years off (first appearing in “The Hound.”) Not that Lovecraft couldn’t have known about the vexy worms and mad Arab and dark tome in 1919. Known and mercifully kept them to himself, until driven by the terrible weight of his knowledge to speak.

What about Carter himself? This is his first appearance and not a super-auspicious debut, given his funky memory, and frail nerves, and fear-frozen immobility at the climax. Carter in “The Unnamable” is still fairly useless in an emergency, but his nerves are up to investigating haunted attics and toting around monstrous bones. And the Carter of the Dreamlands is positively bold—rash, even, though his knowledge of the mystic realms and his alliances with its inhabitants preserve him through his trials. The development of the character often considered Lovecraft’s alter-ego makes an interesting study, one to look forward to in our readings of Dream-Quest and the Silver Key stories.

Pluses: The whole phone conversation thing, which must have seemed tech-to-the-minute in 1919, and it is shivery-cool to think of something besides Warren finally figuring out how to pick up the fallen receiver and tell Carter to shut the hell up already. And a waning crescent moon instead of a gibbous one! And this lovely bit about the graveyard’s smell: “….a vague stench which my idle fancy associated absurdly with rotting stone.” Rotting stone! Love it.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

The guy who tells you how much sturdier and stronger and saner he is than you? The guy who drags you out in the middle of the night and then tells you that you can’t handle anything beyond watching him be brave? That’s the guy who needs someone to look down on in order to feel good about himself. It takes a certain sort of guy to pick a guy like Carter as his closest friend, and drag him around searching for nameless horrors. And Carter, of course, thinks the world of him, and moons about his mellow tenor.

So my first thought is that it wouldn’t actually be a terrible thing to drop a slab over him and head back into town, giving the police a song and dance about inexplicable voices. Probably not the interpretation Lovecraft had in mind, though.

But this set-up actually gets more interesting when you look at Carter’s whole timeline. One of Lovecraft’s major recurring characters, he goes from being deeply ineffective here—failing utterly to undertake a daring rescue—to the seasoned adventurer of “Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath.” And here, at the start of his appearances, he’s already in his 40s. In fact, according to his full timeline he’s a World War I veteran who was part of the French Foreign Legion. So his “nerves” are probably PTSD (which makes Warren even more of an asshole).

On this reading, the rest of Carter’s stories follow him as he recovers his pre-war courage and ability to take action. (One wonders what friends lost in foxholes were going through his mind during the events of “Statement.”) Perhaps the seemingly very different Carter in “Unnamable” is deliberately playing with his own fears, and starting to come to terms with them. One notes that there, he’s the dominant partner in a slightly more equal friendship—the one dragging someone else, with a degree of guilty pleasure, into the world of indescribable horrors. Only this time they’re survivable. Later, in “Dream-Quest,” he’s become a full-blown adventurer, well-versed in the lore needed for survival—though his quests will eventually lead him through many strange transformations.

Moving away from Carter himself, in “Statement” we also get Lovecraft’s repeated motif of weirdly telescoping time. The cemetery makes Carter tremble with “manifold signs of immemorial years.” (Reminder: Carter’s memory is faulty, so lots of things might be immemorial.) The wait for Warren’s non-existent response takes “aeons.”

I have a love-hate relationship with this trope. When it works, we get the intimations of deep time and genuinely vast cosmic gulfs that (almost) eclipse horror with wonder. When it fails, we get the horrifying ancient oldness of houses built a couple of hundred years ago. The former marks some of my favorite passages in Lovecraft—which makes the latter all the more frustrating. If you can make me feel the rise and fall of civilizations over billions of years, the awe-inspiring abundance and terrifying loss implied by the succession of solar races, then why would you try and get me to flip out over a colonial-era cemetery?

But at the same time, things really do feel like they take longer when you’re terrified. Maybe that’s the key with the cemeteries and houses—or at least a way to read them that’s more effective than exasperating—not that their age is inherently ancient and immemorial, but that the stress of the situation makes them feel that way.

Finally, I’m deeply intrigued by the owner of that voice. Because that is a cosmic horror that 1) speaks English, 2) finds it worthwhile to razz Carter but not to attack him, and 3) is kind of snide. Is it Warren’s shade? Is it whatever killed him? Is it something else entirely? Inquiring minds want to know, even though finding out is probably a really bad idea.

Next week, we return to the Dreamlands for a couple of brief journeys with “The Cats of Ulthar” and “The Other Gods.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.

There’s certainly a lot of potential here, but alas the story never really lives up to it. The framing device of a police statement could work quite well, but as Anne notes this is all too vague and too specific. OTOH, it might work in a visual medium, with Carter starting off in an interview rook and things segueing to a flashback. Written out, it needs a slightly different approach, though it does make a nice contrast to the usual fevered letter that is actually a suicide note.

The high tech aspect is also interesting and fits with the police statement conceit. This is something we see crop up several times in later works, like “Whisperer” with its dictaphone recordings and film photographs.

I was also distracted by the deep underground complex in the middle of a swamp. This isn’t the first time we’ve seen HPL ignore the water table. Anne pointed out that Joseph Curwen’s tunnel complex should have been flooded. It seems that Lovecraft may have had even more trouble with geology than he did math.

Lovecraft does seem to have dreamed about Loveman quite a bit. I don’t think they actually met until the New York years, so who knows how the Loveman figure in his dreams manifested. I wonder if the similarity of their names had something to do with it. One could also play all sorts of psychological games with this, considering Loveman’s sexuality, but HPL never seems to have been aware of that.

Perhaps I’m influenced by Carter’s later friendliness toward them, but I tend to see the voice on the other end of the line as a ghoul. Of course, that puts this event in a very different light, especially if you follow Ruthanna’s line of thinking about the power dynamics of the relationship between Carter and Warren.

Very minor, yet again we have a narrator recounting events which happened to someone else in another location and an attempted last line reveal, which works about as well as it always does. Still, greater things would grow from this little story.

Weird Tales: The first appearance of “The Statement of Randolph Carter” is in the February 1925 issue, which doesn’t seem to contain anything else Lovecraftian. It was reprinted in August 1937, which includes Robert E. Howard’s poem “The Soul-Eater”, Henry Kuttner’s “The Jest of Droom-Avista” and Manly Wade Wellman’s “The Terrible Parchment”.

On this day in 1893: one of the true masters of Weird Fiction, Clark Ashton Smith, was born. Happy birthday, Klarkash-Ton!

and a portable telephonic apparatus

I thought for a moment that HPL had invented the cell phone.

A phrase like “necrophagic shadows” is not something I associate with HP. He usually just relies on catalogues of adjectives. The more poetic descriptions are something that I would associate with Clark Ashton Smith, which is why I have come to prefer his work to HPs as I get older.

There’s a meme which goes something like “Poor Lovecraft. Sees a horrific monster and can’t describe it.” Someone recently posted it on the HPL Historic Society’s Facebook page, inspiring a long comment-debate about how descriptive Lovecraft actually was. As some noted, he was very detailed and precise in some stories, but impressively managed to use vast amounts of nouns and adjectives even when discussing the “indescribable.”

My own prose used to consist largely of descriptions, too. Fortunately, I probably wouldn’t have Lovecraft’s luck in getting it published.

The phrase “alternate Florida” reminds me only of Xanth, a land which is very different from Lovecraft-world yet shares many of its features (e.g. interspecies reproduction, weird monsters, excessive wordplay, and noxious bigotry).

@5 AeronaGreenjoy

And rampant sexism. Xanth could do with an invasion of sanity-eating Outer Gods.

RE Lovecraft and geology: It looks like he was concerned with getting many of the then current details right, with respect to Antarctica at least: https://lovecraftianscience.wordpress.com/2013/12/12/h-p-lovecraft-geologist-and-antarctic-explorer/. Maybe his interest developed later or maybe Florida’s geology was too prosaic for him. Now, if it had been called geomancy, or geoism…

@5 & 6: Xanth? Nuke from orbit, it’s the only way to be sure.

Yep. Sexism is Xanth’s bigotry of choice, as racism is Lovecraft’s. And without the excuse of “written many decades ago, in a less enlightened age.” *headdesk*

A couple of weeks ago, a film of “The Unnamable” was discussed. Well, it appears that there is a sequel: “The Unnamable II: The Statement of Randolph Carter”. John Rhys-Davies is in it for some reason and Carter again gets lines like

HOWARD: Do we have to do this at night?

RANDOLPH: Do you really think it would be any safer in the daytime?

I want a Sherlock-style television series with this version of Carter going around investigating eldritch horrors.

If only Darren McGavin were alive, we could have Kolchak and Carter going on an eldritch road-trip across America! Or does that only work with hot guys named Winchester?

Speaking of which, I’m still waiting for Sam and Dean to encounter a shoggoth or two. Or did I miss that episode?

@10: I suppose you could have Stuart Townsend instead of McGavin: the Night Stalker remake’s last episode (“What’s the Frequency, Kolchak?”) was considered to be a substantial improvement on the very weak episodes which came before. Ah, Kolchak: a great series which, like Dirk Gently, was cancelled in spite of vocal protests from all three of its fans.

I don’t watch Supernatural but the Season 6 episode “Let It Bleed” apparently features Lovecraft (Peter Ciuffa) opening a gate into Purgatory. Close enough?

Bah, Purgatory. Not nearly cosmic enough for our Howard. Although he could kind of pass as Dore’s Dante….

DemetriosX @@@@@ 1: My interpretation, both here and in Providence, is that impossible underground complexes are supposed to be an indication of Non-Euclidean Geometry, nefariously hidden just out of sight. Supported here by the fact that Carter is explicitly told that no such complex exists–or could exist–in the area where he claims to be. And supported in “Ward” by the fact that it vanishes.

Walker @@@@@ 4: You know, that’s the assumption with which I went into this reread. But as I’ve been paying attention, for Cyclopean Count purposes, I’ve realized that his descriptive style, and ability to hold back on the adjective salad, actually varies quite a bit from story to story. Some are positively restrained and balanced, and others are… “The Lurking Fear.” It doesn’t even seem to be a change over time–I think it has something to do with how frantically he got caught up in the writing of any given story

AeronaGreenjoy @@@@@ 5: Oh my, that may be the nastiest thing anyone has said about Lovecraft in this forum. Pretty fair, mind you… although if I live for an aeon, no one is going to talk me into doing a Xanth reread! Maybe it’s that Lovecraft didn’t insist on giving the critters against whom he was bigoted quite so much screen time, and wisely faded to black when it came to… activities… with which he had little experience.

SchuylerH @@@@@ 9: It sounds like that version of Carter would offer a much snarkier statement. Not a bad thing at all.

Vast complexes of underground tunnels do exist under Florida; they’re just flooded with water. Florida has a karst geology, which is basically limestone that has been worn through by groundwater, and contains a lot of caves and sinkholes. Something similar happens in the Chiapas region of Mexico, where you will have sinkholes miles inland that are connected to the ocean via underground tunnels. They could easily have been a hideout for Deep Ones.

As a disclaimer, I am neither a geologist nor a Floridian, just a Midwestern landscape architect who lived in Austin for a while (which also has karst geology), and thinks karst landscapes are cool.

It’s obvious: Carter’s graveyard is found in Area X. Maybe it’s related to the tower/pit?

There are several different families of scripts in India that someone from America might not be able to read.

@safarikate: Just last week I was snorkeling in cenotes near Tulum in Mexico. I can’t currently scuba-dive due to circulation/blood problems, but based on the maps and what I could see while swimming, there *certainly* were enough ominous/seductive-looking passages through the rock, as well as some enticing sections just marked in red as “impassible” on the scuba map… ;) Plus, our guide took the time to point out some odd-looking fossils on the walls of the cenote…methinks Lovecraft missed an opportunity there! :)

Didn’t James Tiptree/Alice Bradley Sheldon write a volume of horror stories about the Yucatan region in Mexico? I *think* I may have a copy floating around somewhere (I recently moved and much of my stuff is still in boxes) but I’ve not read it. IMHO, Lovecraft’s Anglophilia led him away from a LOT of rich sources of myth and horror or, worse, led him to misunderstand and misdirect them. (For example, the MESS that is “The Horror of Red Hook.” I have done a LOT of scholarly work on Lilith, I live in NYC, and I won’t even BEGIN to get up on my soapbox about how Lovecraft’s prejudices hurt this story.) :P

@17: The Tiptree is Tales of the Quintana Roo, published in 1986 by Arkham House. I’ve only read “Beyond the Dead Reef” but that featured a suitably hostile and weird zone beneath the waves.

Ok, I found the book WAY more easily than I thought I would. It is “Tales of the Quintana Roo” by James Tiptree, Jr., illustrated by Glennary Tutor and published by Arkham House (who else?!?). Here is the Amazon link: http://www.amazon.com/Tales-Quintana-Roo-James-Tiptree/dp/0870541528/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1421232876&sr=1-1&keywords=tales+of+the+quintana+roo

In the introuction, Tiptree writes, “The Quintana Roo…is a real and a very strange place. It is the long, wild easternmost shore of the Yucatan Peninsula, officially but not psychologically part of Mexico.” Later in the intro, “And beneath the surface, flow tides and ancient currents of great power.”

A very Lovecraftian moment in the second tale, “The Boy Who Waterskied to Forever:” “…every cell in Pedro’s body began to rupture and collapse, and the boy screaming, screaming, like a screaming bag of jelly towards the end…I tell you, we were all a bit more sober after that.”

Remember I said I was snorkeling near Tulum? Here’s what Tiptree says: ”Something always a bit ‘misterioso’ about Tuluum.”

The collection has what might seem to be a heavy-handed ecological subtext to someone who doesn’t transparently like this part of the world as much as Tiptree and I do; from over 15 visits in the past 10 years I can say that local conservation (especially conservation of sea turtles, yay!) is proceeding very well but tourist @@@@@$&*%(%@@@@@ is just as bad as in Tiptree’s time; this time last year I was on Cozumel and I was APPALLED by the amount of trash on the beaches.

Full disclosure: I am a German-American woman with Jewish heritage. I have NO Mexican heritage as far as I know. I apologize if I am being racially/culturally insensitive by talking about a country and culture that is not my own. I just know that, ever since I visited there about 10 years ago now, Isla Mujeres and its surroundings have become just about my favourite place in the entire world and I have adopted Ixchel as one of my patron goddesses. If this is racist or culturally insensitive, I sincerely apologize and would appreciate constructive comments.

Here is how Tiptree ends her book:

“Quintana Roo,” maps call it,

That blazing, blood-soaked shore;

Which brown men called “Zama,” the Dawn,

And other men called names long gone

A thousand years before.

Still songs of gold that dead men sought,

And lures of love that dieth not,

And hungry life by death begot,

Murmur from ocean’s floor.

PS: I didn’t mean to derail these comments away from Lovecraft! ;)

@13: Well, you gave me the idea with “parallel Florida.” :-P I happily gobbled those books for years before the deleterious effects of its misogyny and rape culture overcame the delights of randomness, puns, and monster kink.

@19: Oh, that’s beautiful. I went to the cenotes with my family as a little kid but was too scared to go in them. *sadness* Never been there since then, and have had little luck snorkeling anywhere in the region except Isla Contoy.

Given Lovecraft’s sense of humor, I’ve always assumed that this one is intended as a joke. It’s exactly the sort of thing he’d put in letters to his friends as self-parody, and given the Tuckerization, well.

I can state from personal experience that if read aloud with expression this one can leave a room full of people in stitches.

Safarikate @@@@@ 14: Do I fall down to worship the idea of Deep Ones (and assorted gelatinous allies) in the sinkholes and underground sea tunnels? Yes, yes, I do.

Rush-That-Speaks @@@@@ 22: I think HPL did a lot of giggling whenever he killed off the fictional avatars of his friends, a trend to climax shortly when we consider “The Haunter of the Dark.”

Re Xanth: Ana Mardoll has a series of deconstructions examining sexism in the early Xanth books.

This tale will always have a soft spot in my heat because I’ve used it successfully as the basis for a campfire tale more than once.

@23: Come on now, surely you’ve got to give Bloch his chance to kill off a tuckerised character (“The Shambler from the Stars”)? On a related note, is this reread in any particular order?

@22 & 25: Now there’s a thought. I wonder if any other Lovecraft stories are well suited to performance?

@AeronaGreenjoy: Have you ever tried snorkeling on Isla Mujeres? There is a VERY good reason that people settled there; the waters around the island are FULL of fishes! I’ve snorkeled pretty much all over the Yucatan coast and that remains my best experience. I recommend going to the water park there, Garrafon (http://www.garrafon.com/). The last time I was there, admission was about $45 (US) but drops by about $20 if you arrive in the afternoon. Plus, there’s no limit on how long you can stay in the water! (As someone who is usually the *very* last person back to the shore/boat on snorkeling tours, I especially like this part). And you can walk from the park to the Cliffs of the Dawn and Ixchel’s temple! (I’m not even going to attempt to do justice to the Cliffs; just Google image them and you’ll understand.)

Obviously cultural appropriation is something that concerns me, especially because I, like Lovecraft, come from a position of relative privilege. Lovecraft’s xenophobia has, of course, come up in previous posts in this series. I personally feel like that xenophobia seriously detracts from the horror of his work rather than adding to it (except when he expresses it metaphorically, like through the Great Old Ones and Nyarlathotep, perhaps because then he was less “deliberate” about it). To me, a great example of “xenophobia-as-horror” is Dan Simmons’ novel “Song of Kali.” To me, that perfectly captures the fear that U.S./Western European residents may have about the “Orientalist Other.”

PS: Please understand that I use the word “Orientalist” in the Edward Said sense!

PPS: I can haz Deep Ones in hidden underground sea tunnels, plz? :P

@27: Have you seen this article on Mesoamerican mythos links by Richard L. Tierney?

“But the really striking correlations occur when we study the coastal Mayas of the Yucatan Peninsula.”

http://crypt-of-cthulhu.com/cthulhumesoamerica.htm

@24: Thanks for the link! I’ve been combing the Internet for something like that, but never found anything a fraction as thorough, and shall now squander lots of time reading it.

@27: I took a day trip to Isla Mujeres once, and the sea at the only beach I had time to try snorkeling at happened to be rather turbulent. But Isla Contoy had a lovely, placid bay on one side (and a wonderful colony of frigatebirds). Theoretically, I might someday have a chance to investigate the region again.

Thirded on wanting Deep Ones in underwater tunnels. Or anywhere, really.

Fourth on wanting Deep Ones in underwater tunnels. And after all, I still do need to write that all-underwater Deep One fantasy of manners story. With garden eels, and I think that’s the right ecology for them. May be a while though, and I’d love to see others take on the karst geology as well…

Jaime Chris @@@@@ 17: I’ve been dreading “The Horror at Red Hook” and putting it off in the reading list. But the promise of a Lilith-scholarship-infused rant might just motivate me to add it to the queue.

Must read that Tiptree–it sounds pretty awesome!

Also, welcome to the comment threads! Our discussions have drifted a lot further afield than this–everyone is always welcome to share awesome knowledge and experiences, however tenuously connected to the story at hand.

Rush-That-Speaks @@@@@ 22: You have a point; I can see that pretty easily.

Steve Morrison @@@@@ 24: Oh, awesome. I loved her Twilight deconstructions, but haven’t checked her site in a while.

SchuylerH @@@@@ 26: This reread is in no particular order at all. We pick our stories about a month in advance based on 1) things that we need to double-check for our writing, and 2) trying to keep a balance of different lengths and categories (Mythos, Dreamlands, Poe-ish, Dunsany-ish, etc.). Reader requests might well move stories up in the queue, though we’re trying not to rush through all the fan favorites early on.

Eventually we may start mixing in stuff from other authors, but for now there seems to be plenty of Lovecraft to fill up the list.

@SchulyerH: Thank you for the link; I’ve bookmarked it! I’ve read “The Mound” but thought it was more Bishop’s tale than Lovecraft’s…maybe I’ll write an article on that some day! While I can’t even begin to reach S. T. Joshi or Donovan Louck’s level of scholarship, there is a MAJOR dearth of serious academic work on Lovecraft. :(

@AeronaGreenjoy: Yeah, you really do need to go snorkeling on Isla Mujeres when the water is calm. I tried to snorkel there once in the aftermath of a storm and could see absolutely NOTHING. I’ve also heard that Cozumel has some incredible snorkeling spots but when I was there two years ago I was less than impressed. :(

@R.Emrys: Thank you for your response! :) I am up for SO MUCH RANTING if this read covers “The Horror of Red Hook;” not only have I done some critical feminist work regarding Lilith, but I live in NYC and have been to Red Hook a whole bunch of times!

Happily, my introduction to Lovecraft when I was a teenager was through the Del Rey collection “The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre” (the one with the Bloch intro). Fun side-story: I got into Lovecraft when my mom saw me reading Stephen King, snorted at me, and said, “If you like that, you need to read Lovecraft,” and helped me pick out the collection at the bookstore. While I really didn’t like racist content like “He fell on a narrow hill street leading up from an ancient waterfront swarming with foreign mongrels, after a careless push from a negro sailor” (“Call of Cthulhu), I didn’t encounter much more egregious racism than I expected from a white New Englander writing in the early 20th century. By the time I got to his more objectionably racist stories, I was already hooked on him as a writer. (It probably didn’t hurt that I lived in Boston at the time and was pretty much enraptured – rather than amused – by his “love letter” to New England and Boston at the end of The Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath!)

I’m still struggling with the issue of great writers and their racism/sexism/homophobia/xenophobia/transphobia/cultural insensitity/etc. One of my favourite authors is T. S. Eliot, and we all know what a douchecanoe he was. I adored Pound’s “Cantos” and then I read about him as a person. I still list Heart of Darkness as one of my favourite books but now I know it’s a horrible, racist, colonist narrative. And I’m not EVEN going to get into Shakespeare’s work! I am trying (and have been for about a decade now) to reconcile literary genius with abhorrent ideology.

In any case, I’m TOTALLY up for deconstucting “The Horror at Red Hook” and any other of Lovecraft’s NYC and/or really horribly racist narratives (“Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and his Family,” anyone?). I am very much looking forwards to new posts on this blog! :D

Jaime Chris @@@@@ 31: I seriously hope we will progress to the point where people look back and wonder at all OUR irrational prejudices and neuroses. That could represent the true transition of the species from human to humane.

Hey, fantasists get to fantasize!

@14 et al. Oooooh. If nobody’s written it yet, then somebody needs to write a Mythosian story about Lovecraftian horrors discovered at the bottom of one of those Florida sinkholes. In fact, I just gave myself goosebumps thinking about it. It’s creepy enough when half the house unexpectedly collapses into a giant hole that just spontaneously opened up beneath it, but when there are unspeakable horrors lurking at the bottom?

Actually, if nobody has yet, I might just write that myself. The horrific possibilities are really getting my brain juices flowing.

Florida does seem ripe for eldritch horror, in so many ways.

@34: I agree. But I admit my first thoughts were of the water table too. Any eldritch horrors are going to have to be above ground. Luckily Florida swamps are seriously creepy – not least because of the gators and snakes.

In the Northeast, traditionally “the Gainesville road” (pike, whatever) meant simply “the road to Gainesville”, and it didn’t matter how far away Gainesville was. The Bowery and Broadway in Manhattan were once known as the Boston road and the Albany road respectively.

In his 2014 annotated edition of this story, Leslie Klinger notes that the story never specifies a Florida location, and that there is also a Gainesville and Big Cypress Swamp in Georgia – although, as with Florida, they aren’t very near each other. But there also a Gainseville in Virginia, with any number of cypress swamps nearby.

Of course, that doesn’t truly solve the geological problem, as any deep tunnel in a swamp would be flooded, unless it were constructed of watertight stone or, for most of it, passed through some kind of non-porous stone phase rising up through the swamp from a deeper strata. In either case, it would have to have been dug (or connected) in such a way as to prevent flooding, unless it was constructed before the area around it became swampy.

Klinger also notes that, in The Silver Key, Warren is described as “a man of the South”, which would fit with any of those states.

@37, let’s just assume Eldritch horrors have mad engineering skills.