Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

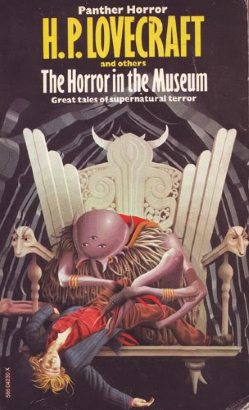

Today we’re looking at “The Horror in the Museum,” written in October 1932 with Hazel Heald, and first published in the July 1933 issue of Weird Tales. You can read it here. Spoilers ahead.

“Even in the light of his torch he could not help suspecting a slight, furtive trembling on the part of the canvas partition screening off the terrible “Adults only” alcove. He knew what lay beyond, and shivered. Imagination called up the shocking form of fabulous Yog-Sothoth—only a congeries of iridescent globes, yet stupendous in its malign suggestiveness.”

Summary: Bizarre art connoisseur Stephen Jones checks out Rogers’ Museum in London, having heard its wax effigies are much more horrible than Madame Tussaud’s. He’s underwhelmed by the usual murderers and victims in the main gallery, but the adults-only section wows him. It holds such esoteric monstrosities as Tsathoggua, Chaugnar Faugn, a night gaunt, Gnoph-keh, even great Cthulhu and Yog-Sothoth, executed with brilliant realism. Jones seeks out the proprietor and artist, George Rogers, whose workroom lies at the back of the basement museum. Rumors of insanity and strange religious beliefs followed Rogers after his dismissal from Tussaud’s, and indeed, his air of repressed intensity strikes Jones at once.

Over time, Rogers tells Jones of mysterious travels in far-flung locations. He also claims to have read half-fabulous books like the Pnakotic fragments. One night, plied by whiskey, he boasts of finding strange survivals from alien life-cycles earlier than mankind. Crazier still, he hints that some of his fantastic effigies aren’t artificial.

Jones’s amused skepticism angers Rogers. Though Jones humors him, Rogers isn’t deceived by pretended belief. Unpleasant, but fascination continues to draw Jones to the museum. One afternoon he hears the agonized yelping of a dog. Orabona, Roger’s foreign-looking assistant, says the racket must come from the courtyard behind the building, but smiles sardonically. In the courtyard, Jones finds no trace of canine mayhem. He peers into the workroom and notices a certain padlocked door open, the room beyond lit. He’s often wondered about this door, over which is scrawled a symbol from the Necronomicon.

That evening Jones returns to find Rogers feverish with excitement. Rogers launches into his most extravagant claims yet. Something in the Pnakotic fragments led him to Alaska, where he discovered ancient ruins and a creature dormant but not dead. He’s transported this “god” to London and performed rites and sacrifices, and at last the creature has awakened and taken nourishment.

He shows Jones the crushed and drained corpse of a dog. Jones can’t imagine what torture could have riddled it with innumerable circular wounds. He accuses Rogers of sadism. Rogers sneers that his god did it. He displays photos of his Alaska trip, the ruins, and a thing on an ivory throne. Even squatting, it’s huge (Orabona is beside it for scale), with a globular torso, claw-tipped limbs, three fishy eyes, and a long proboscis. It also has gills and a “fur” of dark tentacles with asp-like mouths. Jones drops the photo in mingled disgust and pity. The pictured effigy may be Rogers’ greatest work, but he advises Rogers to guard his sanity and break the thing up.

Rogers glances at the padlocked door, then proposes Jones prove his incredulity by spending the night in the museum, promising that if Jones “sticks it out,” Rogers will let Orabona destroy the “god” effigy. Jones accepts.

Rogers locks Jones in, turns off the lights, and leaves. Even in the main exhibition hall, Jones grows antsy. He can’t help imagining odd stirrings and a smell more like preserved specimens than wax. When he flashes his electric torch at the canvas screening the adults-only section, the partition seems to tremble. He strides into the alcove to reassure himself, but wait, are Cthulhu’s tentacles actually swaying?

Back in the main room, he stops looking around, but his ears go into overdrive. Are those stealthy footsteps in the workroom? Is the door opening, and does something shuffle towards him? He flashes his light, to reveal a black shape not wholly ape, not wholly insect, but altogether murderous in aspect. He screams and faints.

Seconds later, he comes to. The monster is dragging him toward the workroom, but Rogers’ voice mutters about feeding Jones to his great master Rhan-Tegoth. That he’s in the clutches of a madman, not a cosmic blasphemy, rallies Jones. He grapples with Rogers, tearing off his oddly leathery costume and binding him. He takes Rogers’ keys and is about to escape when Rogers starts talking again. Jones is a fool and coward. Why, he could never have faced the dimensional shambler whose hide Rogers wore, and he refuses the honor of replacing Orabona as Rhan-Tegoth’s human sacrifice. Even so, if Jones frees him, Rogers can share the power Rhan-Tegoth bestows on his priests. They must go to the god, for it starves, and if it dies, the Old Ones can never return!

At Jones’s refusal, Rogers shrieks a ritual that sets off sloshing and padding behind the padlocked door. Something batters the door to splinters and thrusts a crab-clawed paw into the workroom. Then Jones flees and knows no more until he finds himself at home.

After a week with nerve specialists, he returns to the museum, meaning to prove his memories mere imagination. Orabona greets him, smiling. Rogers has gone to America on business. Unfortunate, because in his absence the police have shut down the museum’s latest exhibit. People were fainting over “The Sacrifice to Rhan-Tegoth,” but Orabona will let Jones see it.

Jones reels at the sight of the thing in the photo, perched on an ivory throne, clutching in its (waxen?) paws a crushed and drained (waxen?) human corpse. But it’s the corpse’s face that makes him faint, for it is Rogers’ own, bearing the very scratch Rogers sustained in his scuffle with Jones!

Unperturbed by Jones’s face-plant, Orabona continues to smile.

What’s Cyclopean: The ivory throne, the bulk of the hibernating god-thing, and the Alaskan ruins in which both are found. For bonus points, the wax museum includes the figure of a literal cyclops.

The Degenerate Dutch: Orabona, Rogers’ “dark foreign” servant—from his name, Spanish or Hispanic—looks like a stereotype at first. However, later events suggest that he’s doing quite a bit to violate those expectations.

Mythos Making: From Leng to Lomar, Tsathaggua to Cthulhu, it’s all here. And we learn that aeons-long hibernation is a common deific survival strategy.

Libronomicon: The usual classics appear in Rogers’ reading list: the Necronomicon, the Book of Eibon, and Unaussprechlichen Kulten. He’s also got the considerably rarer Pnakotic Fragments—from which he takes his god-waking ritual—along with “the Dhol chants attributed to malign and non-human Leng.”

Madness Takes Its Toll: Madness of the “if only” type: Jones would certainly prefer to think Rogers entirely delusional, rather than a homicidal god-botherer.

Anne’s Commentary

Reading this soon after “Pickman’s Model,” I see many parallels. “Horror” is a sort of B-movie version of “Model,” though a ripping good fun B-movie version. In the B-universe, is there much tastier than a megalomaniac genius, ancient gods and sinister wax museums where one might peel away wax to find preserved flesh? We also get the mandatory dark and foreign-looking assistant, but more about Orabona later. I have advance notice from Ruthanna that she spends a lot of time on him, so I’m going to add my speculations, and we’ll see how much fevered imaginations (ahem, speaking for myself only) think alike.

Like “Model’s” Thurber, Stephen Jones is a connoisseur of bizarre art. He’s only a “leisurely” connoisseur, though, not preparing a monograph. In fact, everything about him is leisurely—he seems to have no profession, no job, no obligations. He’s a cipher of a gentlemanly protagonist, whose attributes exist only for the story’s sake. He must be unencumbered by work, or he couldn’t hang out at the museum at will. He must be a bizarre art fan so he has reason to be drawn there. He must have seen the Necronomicon so he can recognize the symbol. Otherwise he need merely be urbanely incredulous when Rogers needs enraging, manfully indignant when Rogers goes too far, and ready to faint at a moment’s notice to prove how even urbane and manly gentlemen cannot bear such terrors. Which means nobody could bear them, except madmen and mysterious dark assistants.

In contrast, Thurber has a distinctive voice, well-served by first person narration. His relationship with Pickman is more complex and intimate, marked by a genuine and deep appreciation of Pickman’s art. Jones may recognize greatness in Rogers, but he treats him more like a psychological curiosity than a friend.

Not that Rogers’ feverish intensity would make many sane friends. He’s a heady blend of mad artist/scientist and religious zealot, with inexplicably deep pockets (who paid for all those expeditions and for transporting giant dormant gods from Alaska to London?) Pickman seems quite steady beside him, circumspect enough to get along in normal society while deliberately tweaking its nose, careful not to reveal his secrets even to a disciple—it’s only a chance photo that betrays his nature.

Photos figure in “Horror,” too. Rogers produces many to prove his stories. Interesting that the photo of Pickman’s model establishes horrible truth for Thurber, while the photo of Rhan-Tegoth fails to convince Jones. It could just be a picture of a wax effigy, itself a false representation of reality. Extra layers of doubt! Interesting, too, the similarity of settings. Pickman’s studio and Rogers’ workroom are both in basements, both in neighborhoods of singular antiquity and “evil old houses.” I like how in “Model” the neighborhood’s age is defined by “pre-gambrel” roofs, while in “Horror” it’s defined by gabled types of “Tudor times.” Yeah, stuff’s more antediluvian across the pond. The vicinity of Rogers’ museum isn’t as cool, though. Southwark Street is refindable, unlike Pickman’s North End lair with its Rue d’Auseil obscurity and otherworldliness.

Pickman lacks one advantage—or disadvantage?—that Rogers has: An assistant. Orabona, to my mind, is the star of this story. Rhan-Tegoth, oh, it’s a serviceable Old One-Elder God, though I’m more intrigued by the dimensional shambler whose hide Rogers dons. Its ruined city is a nice Arctic counterpart to the Antarctic megalopolis of “Mountains of Madness.” It’s far less compellingly described, restricted by the focus and length of this story. But Orabona! He’s as given to sardonic glances and odd, knowing smiles as Houdini’s “Pyramids” guide, as the electro-hypnotic showman of “Nyarlathotep.” This can be no mere Igor, nor can I believe his reluctance to wake Rhan-Tegoth is mere cowardice. I initially wondered if Orabona were an avatar of the Soul and Messenger himself, up to some cryptic intervention with human aspirations and bunglings, as is his wont. Or a Yithian time-traveler? And what might be his mission, either way? I make overmuch, perhaps, of Rogers’ contention that Rhan-Tegoth comes from Yuggoth. That, and its crabbier features, make me think it’s related to the Mi-Go. Maybe their god? Might Nyarlathotep or a Yithian or a cultist enemy of the Mi-Go want to prevent Rhan-Tegoth’s reanimation? Or maybe Orabona’s a Mythos Buffy, in charge of preventing the Old Ones’ return?

Must desist from these speculations before they drive me mad! Nevertheless, I plan to visit Rogers’ Museum next time I’m in London, and if Orabona’s still there, we can chat over tea and biscuits.

Um, I’ll supply the tea and biscuits.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

How often are you actually alone? Really alone, not just a phone call or text message or step outside your door away from companionship? In the modern world—even in Lovecraft’s modern world—it’s not all that common.

I’ve been there exactly once, on a solo vigil as part of a group rite-of-passage camping trip. (The passage in question being the start of college, rather than any more ancient tradition.) The circumstances were as different from Jones’ foolish dare-taking as it’s possible to get: sensible reason, safe location, trustworthy organizers, and most importantly a distinct lack of waxily preserved eldritch horrors. Nevertheless, let’s just say that my 18-year-old imagination managed some of the same tricks as Jones’s, from the warped time sense to constructing monsters in the dark. So this one rang true, and not only that but—unicorn-rare in horror stories—actually managed to scare me.

Lovecraft’s collaboration style varies tremendously. “The Mound” bears distinct marks from Bishop’s involvement, while “Pyramids” seemed to riff comfortably from the core provided by Houdini. This one carries so many of Lovecraft’s fingerprints that one suspects him of writing/rewriting the thing with that effect in mind. While it probably isn’t a very nice way of handling collaboration, it does result in a happy cornucopia of Mythosian bywords and a few intriguing infodumps about same.

Just after “Mountains of Madness,” “Whisperer in Darkness,” and “Shadow Over Innsmouth,” Lovecraft has started to hit his worldbuilding stride and make the Mythos more cohesive. “Museum” calls on every name ever IA!ed in an earlier story, and adds a few new ones. Rhan-Tegoth, retrieved from a ruined Old One city and originally Yuggothi, is one such, and appears only here. As a god, it seems pretty minor—but does suggest that the ability to sleep like the dead isn’t unique to Cthulhu. Gods, like frogs and tardigrades, can go into stasis until ecological conditions (or stars, or sacrifice) are once again right.

But inquiring minds, minds that have suckled on the heady brew of later Mythos stories, want to know: is RT originally from Yuggoth, or an immigrant like the Outer Ones? The crab-likes claws do suggest some relation. And why does its self-acclaimed high priest keep hailing Shub-Niggurath?

Inquiring minds also want to know how the monster-retrieval plot managed to so closely parallel that of King Kong, when both came out in 1933. Was there something in the air?

There’s one more thing—something that looks on the surface like quintessential Lovecraftian bigotry, but then takes a turn for the awesome. What to make of Orabona? On one level he’s a stereotype: a scary dark foreign servant who’s sly and smug and knows more about eldritch things than anyone ought to be able to justify. On another… he’s got an awful lot of agency for a dark-skinned guy in a Lovecraft story. In fact, though he spends most of it skulking around in the background, I could swear that it’s actually his story, with apparent protagonist Jones merely the usual Lovecraftian witness-at-a-remove.

What’s going on, behind the scenes? Orabona takes service with an evil master whose rites he clearly disapproves of—a choice that would probably ping few alarms for readers who don’t expect such characters to have explicable motivation. More charitably, he might fit the Shakespearian tradition of servants who speak for their masters’ consciences without ever doing pesky things like quitting. He follows Rogers to Leng and back, then breaks with tradition by threatening to shoot the soon-to-be-revived god—and then breaks further by actually doing it. And not only hides both the god’s reality and Rogers’ death from the general public, but puts them on display in such a way as to be crystal clear to anyone in the know. This at once protects the general populace from Things Man Was Not Meant to Know (in other Lovecraft stories normally a White Man’s Burden), and puts the Knowing on notice.

I can’t help imagining that Orabona isn’t alone in his efforts. Perhaps there’s a whole order of trained agents, all willing to go deep cover in the households of white dudes who can’t handle the Necronomicon, ready to keep things from going too far when they start trying to revive anthropophagic forces. And yes, I would read the hell out of that story.

Next week, we take a break from reading to talk spin-offs and ephemera—our favorite Lovecraftian music, movies, and plushies, and a few that we wish we could find (though the world may be safer without them).

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.