Walt Disney had never hesitated to tweak his source material while developing animated films. He and his animators happily added and subtracted characters and events, tinkered with characters and character development, and to a certain extent even played with the settings and backgrounds, especially in Cinderella. In some cases, as in Pinocchio, this was in part to ensure that the original source material could be squeezed into a 75 minute adaptation. In other cases, as in Bambi, this was to add plot to what was otherwise a mostly introspective, philosophical work. And in still other cases, as in Cinderella, this was to flesh out a very short story into a 75 minute adaptation. But even in these adaptations, Disney had, for the most part, been true to the main plot and building blocks of the story.

This was to greatly change with Sleeping Beauty, so transformed that in many ways it’s not even the same story at all. And I’m not just talking about taking out the uncomfortable, quasi-rape bits and the ogre. That willingness to completely transform the original story was to fundamentally change the direction of Disney animation.

But before we get to that, a note or two about the most important non-story factor that shaped Sleeping Beauty: the film. And by this I mean the actual celluloid film. The most important technical thing to know about Sleeping Beauty, if you care about these sorts of things, and even if you don’t, is that it was the first Disney feature to be filmed on 70 mm film—more or less the 1950s equivalent to IMAX. For non-technically minded people like me, this means two things: one, the film looks fabulous, and two, 70 mm instead of the standard 35 mm forced Disney animators to put an incredible amount of detail into the work.

(For the most part, I’m going to avoid recommending specific editions of any Disney films. In this particular case, however, be aware that some previous DVD releases of Sleeping Beauty are in the wrong aspect ratios. The more recent platinum and diamond editions restored the original aspect ratios, so if you are still holding on to a 20th century release, this is one case where it’s probably just as well to give into Disney’s ongoing How Can We Reach Into Your Wallet This Time and invest in the more recent versions. And now back to the post.)

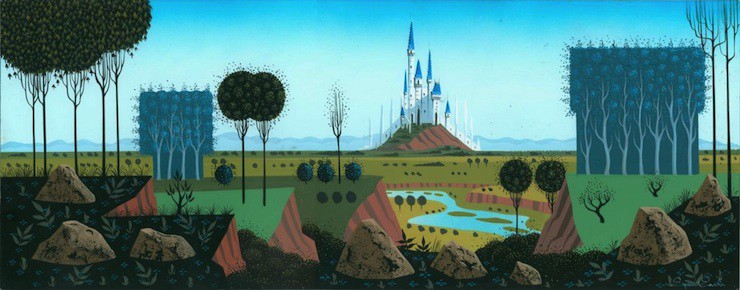

I said “animators,” but what I really meant was “Eyvind Earle,” who not only designed the general look of the film, but almost single handedly created all of the backgrounds for the film. I said “created,” but what I really meant was “drew and painted by hand,” filling out paintings and designs inspired by the unicorn tapestries still on display at the Cloisters in New York City.

If you can, stop at any point just to marvel at the details: the way even some of the square trees in the distant background have individual leaves and all of the carefully painted individual flower petals in the forest scenes; the way each and every stone in Sleeping Beauty’s castle looks different: the images in the tapestries and banners; the pebbles on the floor in Maleficent’s dungeon. Or the scene where Aurora is crying in her castle bedroom: the detail is fine enough to suggest the actual weaving and stitches in a tapestry, several wall hangings and the rich embroidered cloth on the furniture (with details obvious in the painting). The chandelier and the candelabra are clearly made of different metals. The wooden beams well in the background are given individual grains. And then realize that Earle did all of this almost single handedly over the course of a few years—the equivalent to at least 60 multiple, massive fine art paintings. It was the most detailed, beautiful background work Disney had yet created: even the closest comparisons, Pinocchio, Fantasia and Bambi, never went into this level of detail.

It also created headaches for nearly everyone else involved in the film, not all of whom were the sort of film buffs excited about the technical advancements created by 70 mm film. For one, creating that kind of background work by hand and painting all of the animation cels by hand (done by different artists) took time. About four years of time, part of why Sleeping Beauty ended up costing $6 million to produce—more even than Peter Pan, which also had strikingly beautiful background paintings and hand painted cels and ran over budget at $4 million.

For two, this created headaches for animators, who had to design characters who could visually fit into this detailed, angular world. This was not a cartoon background, and so the round, cartoon like creations that had featured in previous work could not, for the most part, be used—even in the scenes focusing on cute animals. Not that the final characters exactly looked realistic—but they were, for the most part, formed of triangles and sharp colored lines, in contrast to previous films. And, complained animators, difficult to bring to life.

This was not a completely new innovation—Alice in Wonderland has some of the same sharp, angled characters, as does the second half of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad. But in those films, the sharp, angled characters stand out as oddities against a usually softer background. Here, it’s the round, cartoonish characters—the three fairies, one of the kings, and two cute bunnies—who stand out—not as oddities, precisely, but as just a bit different. The bunnies, after all, are bunnies. King Hubert is a comic figure—though to be fair, so is the drunken minstrel who appears with him. And the fairies—well, they are magical. And maybe a bit just more than that.

Which brings us to the story, where Disney faced an entirely different problem: in almost all of the original stories, Sleeping Beauty does very little except, well, sleep.

Snow White, after all, escapes to the woods; Cinderella dances; Beauty heads to the Beast to save her father; the unnamed princess of the Princess and the Frog tosses her ball into a well, and bargains to save it; and the little mermaid, as we’ll see, does quite a lot. Sleeping Beauty simply falls asleep. Even in long Tchaikovsky ballet, she falls asleep in the middle of the first act, and spends most of the second act asleep, although she does at least get to dance at her wedding. In one of the original tales, about her only action is to do a strip tease—at someone else’s orders—which was not really the sort of thing Disney was looking to include in its 1950s animated films. She is continually acted upon, not acting, and that created a problem for animators trying to create a story for her.

So instead, they decided to make the story about the fairies and their antagonist, Maleficent.

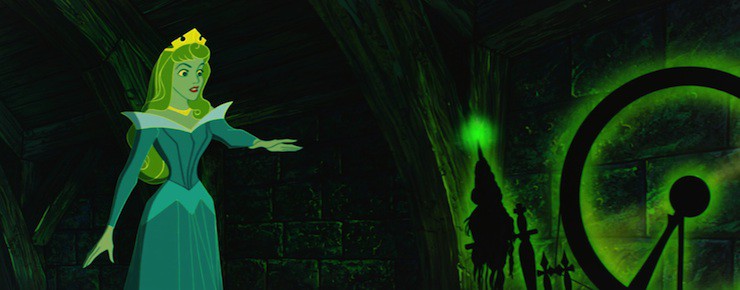

This choice did have the unfortunate side effect of turning the titular character into arguably the blandest of the Disney princesses, and certainly the one who does the least to earn her happy ending. This does work in her favor at least once, when Aurora’s already bland face barely moves as she climbs up the stairs, following Maleficent’s sickly green light. The stillness of her face—admittedly more a side effect of the animation than the character—just adds to the horror, helping to create one of Disney’s most terrifying animated scenes since Chernobog in Fantasia.

But that terrifying moment doesn’t make Aurora/Rose any less boring. I can’t even handwave this by pointing out her innate goodness: unlike Snow White and Cinderella, who grew up in hellish family situations with very little kindness, let alone morality, Aurora has been raised in a supportive, loving atmosphere by three good fairies. She has no reason to turn evil, so her innate goodness seems more a gift than something earned. Oh, sure, she’s not allowed to meet anyone else, or have friends her own age—and in some ways, that’s one of the most awful things that can happen to anyone. But she’s not completely alone, either, and her dancing, singing and elegant curtsey suggest that the fairies haven’t completely neglected her court training and education. And yes, those fairies have lied to her about her heritage—or perhaps just failed to tell her the whole story—and she is devastated when she finds out the truth. But her bout of weeping seems to stem less from finding out that the fairies have kept some rather important information from her, and more from finding out that she’s not going to be able to marry a guy she’s known for a grand total of five minutes, which, yes, I’m all about love at first sight, especially in my animated films, and the girl’s only sixteen, but, perspective here.

The one thing that is slightly puzzling: given her isolation from, well, pretty much everyone, I would have expected her to be just a little bit more shocked during her meeting with Prince Philip. Oh, she’s a little shocked, but this is the first man, let alone prince, she’s ever met, so, really, more shock seems called for here. But then again, as the film keeps reminding us, she’s just sixteen, so it makes absolute sense for her to fall in love instantly with a good looking guy, especially since she hasn’t met anyone else, especially since he can sing and dance, and especially especially since he wears the sort of boots that bunnies can’t resist stealing. And especially especially especially since she’s so unused to meeting new people that she doesn’t even notice the difference between the touch of a boy and the touch of an owl until Prince Philip starts singing to her.

Speaking of Prince Philip—well, yes, it’s true and perfectly understandable that many viewers prefer his horse. (I may be part of that group.) He is, however, definitely a step up from Disney’s two previous princes, if only because he gets to do more than simply meet a girl and kiss her—or dance with her. He talks to his far more interesting horse. He has—gasp—an actual conversation with his father. He gets captured by a woman.

And he gets rescued by three women.

And then the four of them fight a dragon.

In another post on this site, Leigh Butler argued that Sleeping Beauty is Disney’s most feminist animated film. I tend to agree, though I disagree with her that this happened accidentally: it’s a direct result of adapting a story where all of the literary versions feature at least one, and often several, women with agency and power, who are, for the most part, a lot more interesting than the sleeping protagonist princess.

But it’s still remarkable that a film that features three plump, middle aged women rescuing a prince from a dungeon and helping him fight a powerful dragon—who just happens to be a powerful woman in her own right—also just happens to be a film developed in the 1950s that otherwise contains some rather mixed messages about women’s roles. To start with, for instance, in order to protect Aurora, the three fairies need to give up their magic—that is, their jobs—and retreat to a house and focus on domestic duties, like, not subtle, Disney. In a later scene, the three fairies struggle to make a dress and bake a cake by hand.

Sidenote: this scene kinda makes me wonder what, exactly, they’ve been doing for the past sixteen years—ok, dressmaking skills take some time to develop, and I wouldn’t expect any of them to be expert pastry chefs, but still, they should be better than this, as hilarious as the scene is. And I’m a little worried about Merryweather’s observation, 16 years into protecting Aurora, that Fauna has never cooked. Who, exactly, is cooking the meals in this cottage? Let’s hope Merryweather or Flora, especially since Fauna’s idea of cooking includes folding in eggs with the shells still on.

Anyway. Eventually, they give up, and turn to magic—read, appliances and other labor saving devices—which allows Maleficent to find them.

The message: women are safe if they abandon their professional work and labor saving devices for domestic, labor intensive work. It’s a logical progression, perhaps, of both Snow White and Cinderella, which also suggested that women could earn their happy endings through housework. It’s also a rather uncomfortable message in a film where a sixteen year old girl is told that she must marry a prince everyone believes she’s never met—but a similar announcement from a twenty year old boy is greeted only with ineffective protests.

And it’s a message completely rejected by the film itself just a few minutes later, when it becomes clear that the fairies can only save Philip and Aurora from Maleficent by rejecting their ordinary, domestic selves (something they weren’t all that good at anyway) and becoming skilled, magical wielding fairies again.

The result: three kindly grandmother types saving the world. It’s pretty awesome.

Also, let’s all cheer Merryweather on for being able to come up with not just a spell to soften Maleficent’s spell, but an entire rhyme. On the spot. Under major stress. Well done, Merryweather.

Also awesome: Maleficent, one of Disney’s most terrifying villains. And not just because she can transform into a dragon—a sequence animators later regarded as the one of the artistic highlights of the film. She has her weaknesses, certainly—for the most part, she’s really not good at hiring competent staff, with the exception of her raven. As the fairies demonstrate, she can be easily tricked for nearly sixteen years. And as one of the fairies says sadly, Maleficent probably isn’t really happy.

Moment of total honesty here: I feel for Maleficent, really I do. I mean, it’s not just that she didn’t get invited to the christening party and Merryweather is totally mean to her, but, honestly, having to deal with those minions must be incredibly frustrating. The moment when she finds out that her trolls are still searching for an infant sixteen years later is another highlight of the film, with her incredulous, “AN INFANT?” her shriek of “IMBECILES!”, and her heartbreaking realization that her goons are a disgrace to the forces of evil. My heart felt for her. Especially when she later—after all that—throws a party for them, which is incredibly sweet given everything that she’s gone through up until that point. Ok, she might not be great at finding competent goons during the hiring process, but three cheers for throwing an awesome office party for her largely useless goons afterwards.

Beyond throwing great parties, Maleficent quietly dominates every scene she’s in —partly thanks to her height, partly thanks to her black dress, which pops out against all of the brilliant colors of the film, partly thanks to the terrifying musical cues that accompany her wherever she goes. And partly because everyone in the film, except possibly her raven, is terrified of her. For good reason: unlike most of the Disney villains, Maleficent is remarkably successful. She curses Aurora, forces the royal parents to lose their child for sixteen years; puts Aurora to sleep; captures Philip; surrounds the capital with dark, tangled trees, blocking all roads and thus contact with other kingdoms; becomes a dragon; and almost, almost wins. Most Disney villains are brought down by a single antagonist, or their own hubris, or even not really brought down at all. Five people (I’m counting Philip’s much more interesting horse here) have to band together to defeat her—and they barely succeed.

And, of course, she becomes a dragon. Maleficent was not Disney’s first or last animated dragon, and was arguably later eclipsed in popularity by Mulan‘s Mushu (if the number of plush toys is any guide), but she is one of their most magnificent creations, animated with rich, black and purple bitterness. That final confrontation was the most terrifying (and beautifully animated) sequence Disney had created since at least Bambi and arguably Snow White, and nothing would come close to approaching it for years.

But changing Maleficent into a dragon had another impact, well beyond this film. This was not, as noted, the first time Disney had altered the source material, but it was the first time they had altered the source material this much. The Perrault and Grimm versions, after all, have seven or twelve fairies, not three, and no dragon; Sleeping Beauty is asleep for one hundred years, not the single night of this film; the prince is never captured by the evil fairy, and only has to fight briars, not goons and dragons, to reach his princess. The real danger in the Perrault story comes afterwards, with the ogre mother in law; with Disney, once the dragon is defeated, all is well. It was the start of an increasing tendency in Disney films, with a few exceptions here and there, to not just tinker with but completely alter the source material, regularly changing the endings and, as we’ll see, many other things. Interestingly, with the exception of The Little Mermaid, going forward, the biggest alterations would be made to source material from books, not fairy tales, particularly with The Fox and the Hound, but we’ll get to that.

Since I mentioned the musical cues, we should also probably discuss one of the film’s other strengths: the score. Oh, not the syrupy song that Aurora sings and later dances to with Philip. That song has failed to reach the list of most popular Disney songs for excellent reasons. But the rest of the music, based on portions of the score that Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky had composed for a Sleeping Beauty ballet. This was in part a cost saving measure—the score was not copyrighted in the United States, and using it saved Disney the cost of hiring a composer for the entire film. But it was also a brilliant choice that melded well with the film’s rich, quasi-medieval look and added emotional depth to multiple scenes. For several young viewers, it was their first (and perhaps only) exposure to Tchaikovsky at all.

It’s only fair to note that some Tchaikovsky purists decried the result, especially when, decades later, Disney decided to trademark the term Princess Aurora, the name used in the ballet. As far as I know, Disney has not attempted to use the trademark to control or veto performances of the ballet, but that did not make this a popular move among Tchaikovsky scholars.

Oh, and trivia note: It’s also the only Disney film worked on by Chuck Jones, better known for his Looney Tunes/Merrie Melody cartoons over at rival studio Warner Bros, though he returned to WB before he had done enough work on this film to be credited.

Chuck Jones’ departure, however, did not affect the rest of the animation much: between the backgrounds and the animation—which also, for the first time since Bambi, featured multiple characters moving in the multiple scenes, a sign, perhaps, that having gone this far, Disney felt it might just as well throw more money at it—this was the studio’s best looking, richest film since the pre-World War II. Spectacular animation, adorable animals, splendid villain, narratively unnecessary dance sequences, cake ingredients hurrying to get themselves baked, syrupy songs, bunnies, a Disney princess—this may be perhaps the quintessential Disney animated film.

It was also a box office flop.

Whatever the reason—a lack of appreciation for Tchaikovsky, impatience with long scenes involving blonde girls singing to adorable animals hopping around in stolen boots, the decision to make three grandmotherly types the heroes of the film instead of the sidekicks, or the fact that, despite some amusing moments here and there, Sleeping Beauty is more remarkable for its beauty and emotional power than its humor—it flopped. Badly.

Decades later, Sleeping Beauty was to be recognized by many critics as one of the greatest of the Disney animated films, ranking with Pinocchio and Fantasia as the highlights of Disney animation until the computer age—a judgment that watching the films in order like this does seem to verify. But in 1959, Walt Disney had only his guts and box office receipts to guide him. Deciding that Sleeping Beauty was too emotionally cold, not to mention expensive, he ordered several changes.

First, he decided that Disney would slow down, just a little, on the costly animated films that never seemed to stay within the original planned budget. This was to be studio policy for nearly three decades until Jeffrey Katzenberg reversed it in the late 1980s. Second, Disney needed to retreat from fairy tales and focus on funny animals. That was studio policy up until The Black Cauldron, a financial disaster that was immediately followed by—you guessed it—films focused on funny animals. (This is also one reason why The Little Mermaid has funny animals.) Third, the beautifully detailed, hand painted backgrounds were out, absolutely out. This was occasionally fiddled with—mostly in The Jungle Book and one or two scenes in The Many Adventures of Winnie-the-Pooh—but in general remained studio policy until the advent of computer animation made the detailed backgrounds financially feasible again, as we’ll see in later films.

And fourth—if the animation studio planned to remain open, it was going to have to find some cheaper way of dealing with animation cels. Hand inking and hand coloring—all out. Absolutely, positively out.

One Hundred and One Dalmatians, another animation landmark, if for entirely different reasons, coming up next.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.