Big Damn Swords, orange blood, gods made of future metal… Brandon Sanderson’s books make use of a great variety of epic fantasy settings and magic systems, and each new series and short tale introduces yet more. 2015 marks ten years since Sanderson’s first fantasy novel Elantris was released, and since then the author has filled the shelves with so many different worlds that the ones that share the same grand universe are dubbed, simply, “The Cosmere.”

This variety of fantasy worlds sharing certain characteristics is not a new construct. (Role-playing games create this solely by virtue of publishing sequels.) But over the course of reading Sanderson’s novels, I started to notice more than a few parallels that the Cosmere has with the classic RPG series Final Fantasy.

Note: There are some spoilers ahead for existing Sanderson books in the Stormlight Archive and Mistborn series, as well as existing games in the Final Fantasy video game series. Nothing you don’t already know if you’ve read the books/played the games.

1. What if all the Final Fantasy games took place in the same universe? Enter: Brandon Sanderson’s Cosmere.

The FF games have vibrant characters and detailed worlds, but they also share certain elements: like the random monsters that plague your party, the weapons you can find, and how the presence of demi-gods (in the form of summonable beings) affects human society on that world. It’s fun for a player to imagine how a character from one game world (like Cloud from Final Fantasy VII) would deal with a situation in different game world (like the fantasy-medieval setting of Final Fantasy IX). Would he run to save Princess Garnet but end up stumbling to his knees, clutching his head? These are important questions, people.

Despite a few shared characteristics, chocobos, and cheeky cross-references, none of the Final Fantasy games actually take place in the same universe. Although they DID all cross over in a weird “non-canon” fighting game called Dissidia Final Fantasy, which strung all of the characters and settings together in with a loose dimension-crossing storyline. It provides the same kind of glee one gets from mixing everything in the toybox together, like so:

From a fan’s perspective, the urge to combine these games into one universe is always there, and it makes me wonder if this desire was part of the huge mix of inspirations that Sanderson must have been exposed to during his pre-publication writing period. The Final Fantasy games don’t really mix well without a lot of fan-created apparatus to hold them together, but what if you weren’t beholden to the various rules present in FF games? What if you could create a common mythology that allowed for the creation of several different types of fantasy worlds? And that allowed for the narratives in this worlds to grow naturally into bridging the gap between worlds (and book series)? This, in essence, seems to be what Sanderson is doing with the Cosmere.

2. Optimism and Agency in Final Fantasy and Sanderson’s Cosmere.

Final Fantasy games allow the player embody characters that actively engage with their worlds, often following a narrative chain that turns into full resistance against that world’s order. In the earliest FF games, this was mostly because, well, it’s a game. You have to be a character that goes and does things, even if you’re something as random as Pac-Man or Q*bert, or else it’s not a game. Over time, these player characters are given more and more complex back stories, moving past the trope of “well, you’re destined, so…” and into narratives where the main character stumbles into the action. FF IV’s protagonist Cecil doesn’t realize the larger fight he’s in until he opens a box and unknowingly destroys a village. FF V’s protagonist Bartz literally has the plot drop on him (in the form of a meteor). VII’s Cloud would be happier to be left alone, and VIII’s main character Squall would be happier as a stain on the wall. Over the course of these games, these characters all discover the motivation for their struggle. In essence, their growth is tied to their choice to fight. Nearly every character in FF VI faces this personal struggle, and by the end of the story it becomes clear to the main character, Terra, that choosing to struggle means choosing to remain present to the world around you.

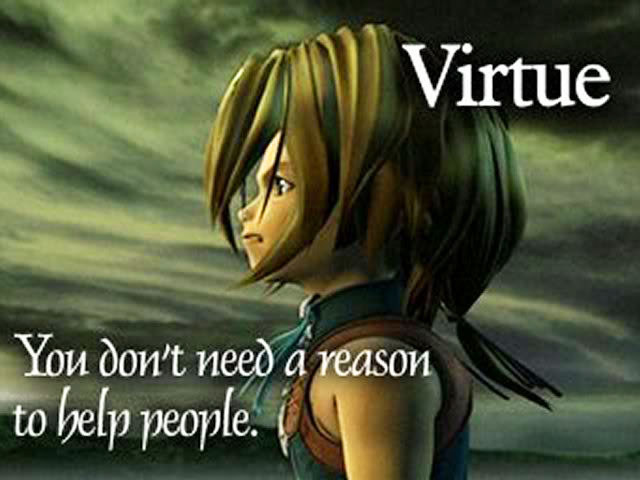

Choosing to fight for your world means having faith, and believing that your actions can lead to a better environment for others. Optimism in a better world motivates this faith, and in the mid to late 1990s and beyond, the Final Fantasy series began making this optimism far more central to the main characters. Final Fantasy IX, X, and XII all feature explorative, supportive, optimistic main characters in the form of Zidane, Tidus, and Vaan, respectively.

(Although Tidus’s optimism can get a little excessive.)

Final Fantasy’s optimistic main characters are key to understanding the worlds they inhabit, mostly because they’re all so eager to help and explain and change things about the world for others. Many of the main characters in Brandon Sanderson’s Cosmere share this trait, something that has not gone unnoticed by the author himself:

In addition, we establish very quickly why Kelsier [in Mistborn] smiles so much. I’ve been accused of being a chronic optimist. I guess that’s probably true. And, because of it, I tend to write optimistic characters. Kelsier, however, is a little different. He’s not like Raoden [in Elantris], who was a true, undefeatable optimist. Kelsier is simply stubborn. He’s decided that he’s not going to let the Lord Ruler take his laughter from him. And so, he forces himself to smile even when he doesn’t feel like it.

Sanderson uses optimistic characters in the same manner that Final Fantasy does, to explain the world and push the narrative forward, but he also takes care to evolve his depiction of optimistic people from series to series. Elantris starts with a full-fledged optimist, Mistborn offers a begrudging and reactionary optimism in Kelsier, and the Stormlight Archive offers a complete deconstruction of the concept of optimism in the form of Kaladin, who struggles constantly with depression. We don’t know how Kaladin’s journey will change his optimistic viewpoint. In the same manner, Final Fantasy X players don’t know how learning more about the dystopic world of Spira will change Tidus.

In fact, of all the Final Fantasy games, I find the parallels between Final Fantasy X and the Stormlight Archive to be the strongest.

3. Stormlight, Pyreflies, Spheres, and Fiends.

In the Stormlight Archive, stormlight itself is “radiant energy given off by highstorms that can be stored in gemstones,” since the gems and the stormlight itself both have value, these spheres are used as currency on Roshar, the world of the Stormlight Archive. Stormlight can be re-manifested by a person to achieve gains in that person’s strength, speed, stamina, and defense. We have yet to achieve confirmation that stormlight can manifest (or at least trigger a manifestation) of spren, the strange little creatures that appear in relation to emotions and also just because, but they can definitively provide a connection between a person and stormlight. Stormlight may or may not have its own will.

In Final Fantasy X, on its planet of Spira, energy takes the form of small globular pyreflies when condensed, and they can inhabit or condense further into spheres that hold memories or perform mechanical functions. Pyreflies can be passively absorbed by a person to achieve gradual gains in that person’s strength, speed, stamina, and defense. In the game, we learn that pyreflies are essentially a basic visible form of the energy binding all living beings. This energy can augment, record, and even re-manifest into aeons, strange and hugely powerful creatures; fiends, monsters that form from the pyreflies of restless beings; and individuals with strong memories associated with them. Later, we learn that a person’s own strength of will can allow them to reform themselves after dying, and that the world of Final Fantasy X is actually full of the living dead. Pyreflies, as such, often have their own will.

At one point in the game, you glimpse the realm where these pyreflies, the energy born of living will, all gather. It is a vast and eerie vista, essentially an afterlife containing all memories of all lands and peoples, called the Farplane.

“ … a place with a black sky and a strange, small white sun that hung on the horizon … Flames hovered nearby … Like the tips of candles floating in the air and moving with the wind … An endless dark sea, except it wasn’t wet. It was made of the small beads, an entire ocean of tiny glass spheres…”

That isn’t the characters of Final Fantasy X describing the Farplane. That’s Shallan describing the Cognitive Realm, also known as Shadesmar, in The Way of Kings, the first novel in Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive series. Little has been revealed about the Cognitive Realm, but we do know that the act of thinking, in essence creating new memories, adds more real estate to the Realm. Possibly in the same manner that a Spiran’s will is added to the Farplane upon their death in Final Fantasy X.

Eventually, we find out that the source of Spira’s troubles (a giant Cloverfield monster aptly named “Sin”) is made of pyreflies and held together by the will of an angry alien entity called Yu Yevon. Yu Yevon’s true form isn’t human at all, rather, it appears as an extraterrestrial parasite. But Yu Yevon can manipulate the energy of Spira, the pyreflies, to create defenses for itself, so the main characters must sever that connection in order to have any chance of hurting this terrible alien god parasite.

In a sense, Yu Yevon’s actions in Final Fantasy X are a miniature version of what may have happened in Sanderson’s Cosmere. Currently, we know that the Cosmere was created by (or inhabited by) a god-like being known as Adonalsium. This being was shattered into 16 shards, each carrying an aspect of Adonalsium’s power, personality, and form. In Final Fantasy X, the malevolent Yu Yevon splits its attention and conducts its business through a variety of forms, the aeons and Sin in particular, each with their own power and personality. Is there a malevolent force behind the shattering of Adonalsium? And is that malevolent force acting through the shards? It’s impossible to say.

Maybe Adonalsium was shattered by…

4. Big Damn Swords.

Really, really lucky (or privileged) individuals in the Stormlight Archive have access to Shardblades. These are, in essence, enormous magical swords that would be impossible for a regular person to wield. Just look at how big Oathbringer is!

Big Damn Swords are not unique to Sanderson’s Cosmere, epic fantasy, or pop culture in general, so it’s no surprise that the Final Fantasy series makes use of them as well. Probably the most notable Big Damn Sword in the whole series is the Buster Sword, wielded by the spindly-armed, spiky-haired main character Cloud in Final Fantasy VII. (Pictured above.) Cloud’s foe, the eerie Sephiroth, wields an even LARGER sword. Later on in the series, the character of Auron from FFX gets in on the big sworded-action, too, although he at least wields his Big Damn Sword properly, using its weight to provide some extra damage to fiends instead of swinging the thing around as if it were weightless. (Auron is full-measures, full-time.)

Big Damn Swords are just cool. And because they are, fans have created replicas of both the Stormlight Archive’s Shardblades and Cloud’s Buster Sword.

5. Other Visual Parallels

Whenever I read the Stormlight Archive or play Final Fantasy there are other small parallels that come to mind. They aren’t really parallels–they’re too small to be–but nevertheless the imagery is linked in my mind.

For one, whenever I read about a chasmfiend in Stormlight Archive, I always picture the Adamantoise monster from Final Fantasy X.

(“Except with a shrimp mouth,” Carl informs me. He’s such a good friend.)

Additionally, whenever we return to the Bridge Four crew, I can’t help but joke to myself… bridges are important! For doing the king’s bidding!

For getting places!

Too soon?

6. Mist

One final parallel that the FF games have with Brandon Sanderson’s Cosmere is mist. When I first picked up Mistborn, the mist-heavy setting alone excited me because I’m a big fan of Final Fantasy IX, which counts a planet shrouded in Mist as a major plot point. The Mist is used as fuel for airships, machines, and magic and it’s only later that you discover that, much as the mist in the Mistborn series is the soul of Preservation, the Mist in FFIX is comprised of the souls of beings from another world.

Mist appears again in Final Fantasy XII and in largely the same function, although in this case it’s not comprised of souls (hooray!) and only appears in places where magic has been used to an extreme extent. Mist in this game acts as an atmospheric wound upon the world.

While there are certainly a few parallels between Final Fantasy (particularly FFX) and Sanderson’s Cosmere, I severely doubt that those parallels could be used to predict the ongoing story or structure of the Cosmere. There are too many fundamental differences in both systems. The Cosmere doesn’t make use of elemental crystals, or airships, or even the summoned beings that are so key to the mythology of most the FF games. Similarly, while the FF games contain the seeds of ideas we see in the Cosmere, those ideas aren’t nearly as fleshed out as they are in Sanderson’s books. There are no interactive charts mapping out Allomancy, Feruchemy, and Hemalurgy, no hierarchies of shards and worlds they’ve interacted with, no sub-structure of realms and their effects on the aforementioned. None of this complexity exists in Final Fantasy.

But I wouldn’t be surprised to find out that playing Final Fantasy inspires Brandon at times. Especially since, way back in 2011, Brandon was listening to “To Zanarkand” as he finished A Memory of Light, the final volume of Robert Jordan’s epic Wheel of Time series.

Play us out, Uematsu.

Chris Lough writes a lot for Tor.com, not really on Twitter, and is working on a mind-blowing expose on how all horses in fantasy fiction are really just two people in a horse costume.