Her name was Kimbralin Amaristoth: sister to a cruel brother, daughter of a hateful family. But that name she has forsworn, and now she is simply Lin, a musician and lyricist of uncommon ability in a land where women are forbidden to answer such callings—a fugitive who must conceal her identity or risk imprisonment and even death.

On the eve of a great festival, Lin learns that an ancient scourge has returned to the land of Eivar, a pandemic both deadly and unnatural. Its resurgence brings with it the memory of an apocalypse that transformed half a continent. Long ago, magic was everywhere, rising from artistic expression—from song, from verse, from stories. But in Eivar, where poets once wove enchantments from their words and harps, the power was lost. Forbidden experiments in blood divination unleashed the plague that is remembered as the Red Death, killing thousands before it was stopped, and Eivar’s connection to the Otherworld from which all enchantment flowed, broken.

The Red Death’s return can mean only one thing: someone is spilling innocent blood in order to master dark magic. Now poets who thought only to gain fame for their songs face a challenge much greater: galvanized by Valanir Ocune, greatest Seer of the age, Lin and several others set out to reclaim their legacy and reopen the way to the Otherworld-a quest that will test their deepest desires, imperil their lives, and decide the future.

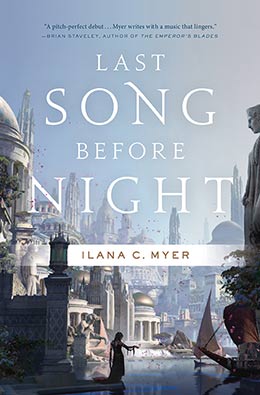

Read an extended excerpt from Ilana C. Myer’s high fantasy novel Last Song Before Night—available September 29th from Tor Books!

Chapter 1

Music drifted up to the window with the scent of jasmine; a harp playing a very old song of summer nights, one Dane knew from childhood. The merchant smiled to himself as he scratched out the last figures in a column, the result of a long evening’s work. This was why he liked to work in a room that overlooked the street. Especially now in summer, when the Midsummer Fair brought singers and all manner of entertainers to Tamryllin. But especially singers—Academytrained poets whose art was the pride of Eivar even now, centuries after their enchantments had been lost. Dane’s wife complained of the noise, but that was women for you.

She complained about a lot of things lately, despite the considerable wealth Dane Beylint had hauled to her door in all the years since they were wed. It was tiresome. It was worse than that—it exacerbated Dane’s anxiety in what she should have realized was already a tense way of life.

Ships came in, ships went out—you never knew if your fortunes might sink with one of them. Certainly he had insurance, but those agents invariably tried to cheat you in the end. Just a month earlier, Dane had lost a ship on the seas in the far east, an entire cargo of jacquard and spices gone forever to Maia. He was one of the few merchants of Tamryllin bold enough—and with the resources—to send ships to those distant waters, which were said to run red with blood.

Dane didn’t believe any such nonsense. He suspected the ships’ captains liked to spin tales as a ploy to raise their rates. To say nothing of the insurance agents. But there was no question that it was risky, no question that he—Dane Beylint—was renowned for where he dared send his ships, how much he risked. Between his boldness and his informers at court, Dane kept his wife in silks and pearls, his sons standing to inherit an empire. And his daughter—she would marry well; there was no question of that.

His work for the day done, Dane saw there was an hour’s worth of oil left in the study lamps. Rather than call the servant to light his way to bed, Dane paused to consider the black satin cloak, lined with gold brocade, draped across a chair. It had just arrived that day, to his delight. Inwardly he calculated its assembled cost: two sumptuous imported fabrics sewn together, the impeccable tailoring. The gold clasp he’d ordered on impulse, that would glitter at his throat under lamps. Yes, it was costly, but he was to attend the Midsummer Masque at the residence of the Court Poet himself; for that you spared no expense.

More valuable was the mask that Dane now lifted from the desk and set over his face, gazing at himself in the silver-backed mirror that was itself worth a fortune. His eyes looked back at him from within a frame of black, patterned with gold leaf. Even the evening lamplight danced on that gold. An ornamental sword, the hilt and scabbard perfectly matched, would complete the ensemble. He had commissioned the mask and sword from a master craftsman in Majdara; they were just different enough from the traditional Eivarian style that he was certain to stand out. And Dane liked the idea of standing out. He had deliberately not asked his wife to attend the masque with him.

That line of contemplation was a bit too stimulating at this time of night, when he needed to sleep. He had an eye on more than one alluring prospect at court; ladies weary of their arranged marriages and intrigued by a man who was experienced, by all accounts, in the dangers of seas that ran red with blood.

As if divining Dane’s thoughts, the singer outside had ended his song of the summertime and now struck up a ribald ballad, its brisk rhythm drastically at odds with the hush of night. Dane couldn’t make out the words—it was something about seduction. But then, most of them were.

His informers at court were helpful in these matters—keeping Dane abreast of a prospect’s level of interest, of opportunity. Frequently absent husbands, for example, could be a convenience. But that was a frivolous use of his contacts’ services; more often, Dane benefited from them in other, more substantial ways. When the king was on the verge of betrothal to his southland queen, years ago, it was Dane who had caught wind of it weeks in advance; who had procured an emerald so fine, so prodigious in size, it was still discussed at court to this day. A gift from the king to his intended bride, set in gold as a pendant for her to wear. Such acts tallied over years could consolidate a man’s power, extend his sphere of influence even in a court as harshly glittering as that of the capital.

Dane lowered his mask, felt the warm summer air on his face. An owl called at the window, softly. The song was moving into its last phase, and Dane hoped for his wife’s sake that the poet was nearly done. Well, and for his own sake, too. He would be heading to bed and hopefully sleep in just a moment. But first, as he stood at the window and observed the startling edge of the scythe moon, there were things to consider. Or savor.

Days ago, one of his informers had told him of something that was interesting… singularly interesting. An opportunity, in fact, not likely to arise again. Dane had sent a note to the palace, pressing his advantage. It was precisely through such shrewd stratagems, such creative mechanisms, that he kept his wife in exquisite fashions—not that she would ever appreciate it. His children were ungrateful as well, but then that was all but a given. Luckily, Dane found solace in his work and its rewards. Particularly the rewards.

Silence, now, at the window. It occurred to Dane that the song had cut off abruptly, mid-verse. He wondered if some enraged, sleepless citizen had knocked the poet flat. Dane had a liking for music, and even for poets—brash and arrogant as they were—and so hoped not.

Once again taking note of the moon, the scent of summer jasmine, Dane thought—not for the first time—that if he had not had a family to support, perhaps he too could have been a poet. Wandering from hearth to hearth, composing songs that would make even the most diamond-glimmering of the aristocracy tremble with admiration or lust. His singing voice, he was told, could be impressive when he put effort into it. But poets didn’t have families. Even the greatest poet of the age, Valanir Ocune, was said to wander without a home. And such was Dane’s nature—forever putting the needs of others before his own.

It was while occupied with this particular thought, this melancholy satisfaction, that Dane heard a new strain of music break the silence. But this was not music such as he had ever heard before. Dissonant, it ripped across the night. Across his soul. And then blackness before his eyes, and then nothing at all.

When Dane awoke, he was bent painfully backward over a hard surface. The room was bright with the glow of candles, the brightness nearly blinding. Dane began to scream.

The man in his line of sight held a knife outstretched. His face a mask of red. Another moment, and Dane realized both who the man was, and that the mask was blood.

“Dane Beylint,” the man said and swiped the knife at Dane’s throat. Mercifully, it was quick, the main artery of the neck severed at once. Around Dane’s now-slackening face, a pool of blood collected into a trough in the table. It was neatly done.

* * *

Lin woke with a gasp. She’d tugged the blanket from Leander and clung to it, though the room was hot. She was shivering.

“For gods’ sake, Lin,” Leander muttered blearily and made a grab for the blanket. “Give it back.”

Her fingers went limp; she let him pull the rough fabric to himself. From the bed she could see the moon, a white grin against the night. Lin shook her head; that was not a helpful metaphor. But the terror that had pierced her lingered.

“What is it?” Leander said now. He must have felt her shivering.

Lin swung her legs out of bed and approached the window. Outside, she could see a back alley, and not much of that. The smell that wafted up from it had induced them to close the window even against the summer breeze. “I heard a scream.”

“You were dreaming,” said Leander. “Or… you know what goes on in places like this. Nothing terrible, though.”

She was glad he couldn’t see her, that his face was still buried in the flat mound that passed for his pillow. Nightmares were certainly not new territory for Lin. She didn’t know why this particular one had bitten so deep. Already, the images were fading—the flash of a long knife, candles. But the tortured shriek—that was new. Worse than any nightmare she’d ever had.

“Leander, can I play us a song? Just one?” Lin tried to sound more casual than she felt. The harp was his, and he disliked for her to even touch it. And he had been sleeping.

But perhaps she underestimated his kindness. At times he could be generous. She had cause to know. “You’re crazy,” he said. In the dimness she saw him stretch his arms wearily. “I could swear you invented a nightmare to get your hands on my harp. One song.”

She nodded, stroked the metal strings of the instrument with reverence. In that moment she was so grateful to be in this room and with this harp in her hands that tears pricked her eyes. “That’s right,” she said. “I’ll sing you to sleep again.”

* * *

The eyes were watching her. But no—they were hollows, not eyes, cut into the mask that sat on her bedside table in a spill of moonlight. Yet Rianna felt watched as she pressed her ear to the bedroom door. Silence in the hallway.

A stab of guilt in her, briefly, at the sight of the magnificent mask, a gift from the man she was to marry. But then she was on the move again. She cracked the door ajar, smoothly quiet on hinges she had oiled earlier that day with this moment in mind. All that day her thoughts had been arrowing to now, past the toll of midnight when at last she could count on her father’s being asleep. Even if he had stayed up very late writing figures in his account books or pacing the carpeted floor of his study, interminably, fueled by wine. A merchant such as Master Gelvan had many cares.

Rianna’s father was not one of those men—most often wealthy— who locked their daughters up at night. And for years, she would have laughed at the thought. They would both have laughed. He joked that the seventeen-year-old Rianna was already as sober as the most venerable spinster, obedient almost to a fault.

She slid around the door, stepping carefully in satin slippers. These allowed her to glide on the tiled floor and then on the stairs that led to the rooms below. By night, the interior of the Gelvan house had an eerie way of reflecting moonlight from the white marble of the floors and pillars, of which Master Gelvan was so fond. He’d had the stone shipped from the quarries of the south at considerable expense. Rianna thought her own shadow on the gleaming floor was like a pursuing spirit, felt a shudder.

How Darien would tease her, if he knew.

A thought that was mortifying and alluring at the same time. Her ears drummed to the rhythm of her heart.

It was when she reached the door of Master Gelvan’s study that Rianna heard voices. Her father, and one other. Her heart thundered now, but she kept her composure; she still had time to tiptoe past the study door—open only a crack—and escape to the main room and, from there, out to the garden.

“…An itemized note on the body had his name,” said the voice that was not her father’s. Rianna thought he sounded familiar, and then realized—it was one of their kitchen servants, Cal. “It seems to confirm your suspicion—that there is a connection to the other killings.”

“His blood was drained like the others, Callum? You are sure of this?” Master Gelvan’s voice, low and urgent.

“I spoke with Master Beylint’s servants. It was the same wound. But instead of the streets, Master Beylint was found in his own garden. The night guard is being questioned.”

Rianna stood frozen. She clasped her hands over her mouth to stifle the sound of her breath. The murders. An ugliness that had begun in the past year, but always at a distance: bodies found sprawled in the more ramshackle streets, the poorer districts of Tamryllin. Master Gelvan would have concealed the knowledge from her if he could, but the servants talked. The killings were all done the same way: a knife wound to the throat, the blood drained and nowhere to be found. Six there had been so far.

Dane Beylint, the seventh, was a man like her father—a merchant, with close ties to king and court. And not found in the streets. His garden.

“I will go myself, tomorrow, to convey my condolences to the family,” said Master Gelvan. “Thank you, Callum, for doing such good work. For the rest—the invitations go out tomorrow. And now I think there are some names we must add to the list.”

Rianna crept swiftly past the study and toward the main room. The invitations. Her father was of course referring to the Midsummer Ball that he was to host this year, as he did every year. Everyone in Tamryllin who was of any importance would attend, including the king himself—and his Court Poet, Nickon Gerrard, said to be the most powerful man in Eivar. The entertainment would comprise some of the most skilled performers who had journeyed to Tamryllin for the festival. So it had been every summer for as long as Rianna could remember.

This year was different. Darien would be there, performing, along with his friend Marlen. This year she had her secret to conceal from the world… at least until the contest was over.

As she turned the handle of the second door she had oiled that day—which led out to the garden—Rianna thought of her father’s voice calmly invoking blood and wounds. It was too strange. And Cal… ? With his heavyset frame and mournful eyes, Rianna had often thought he resembled a hound. That was, if hounds spoke of animal innards and turnips and the turnings of the harvest seasons.

What had Master Gelvan’s kitchen servant to do with murders? Why was either of them awake so late?

Then the scent of roses enfolded her with the warm summer air, and Rianna almost forgot her disquiet when she caught sight of them waiting at the base of the cherry tree.

* * *

It was a long time since Darien Aldemoor had last broken the law. The last time had been for the same reason, a girl. Marlen had been with him then, too—his friend’s much taller frame lending itself, on that occasion, to reaching an inconveniently located gate bolt.

Darien grinned at the memory. His and Marlen’s success that night had made them even more a legend among the Academy students, the lady in question a stunning creature who had inspired one of his most admired songs. She had soon afterward married a wealthy lord, as stunning creatures did tend to do. But not before Darien had made her famous, in image if not in name, from the Blood Sea south of Eivar to the bare mountains of the north.

“What are you smiling about, lunatic?” Marlen growled. His dark hair veiled his eyes in the moonlight.

“You,” said Darien. “Now hush. We could get stopped here by guards.” The street was quiet and steeped in scents of midsummer. Jasmine and honeysuckle twined in starry abundance on walls that sealed the mansions of Tamryllin from the streets. Darien thought sadness was distilled in those scents despite their sweetness, from the knowledge of how short a time they would last.

An odd thought to have while breaking into a rich man’s home. Yet such thoughts tended to go to a reservoir in Darien’s mind, to the place where songs were born. And then women wondered how he knew about sadness—and loss, and ravaging love—when otherwise a more cheerful person would have been hard to imagine.

A person who was now about to cheerfully commit a crime. Darien muttered a prayer of thanks to Kiara for the slenderness of the moon. Then: “Follow me,” he said, and moved to another tree. A rustling sound told him that Marlen followed, grumbling under his breath.

“Stop complaining,” murmured Darien. “We will sing of this later.”

“That we will,” said Marlen. “If in prison, a tragic ballad. Otherwise, a farce.”

“You’re too cynical,” Darien admonished him. Down the alley, he remembered. A fault in the garden wall.

They crept down the alleyway beside the mansion, where they reached the square into which the gardens faced. Each with its own high wall, affording the treasure of privacy to wealthy inhabitants.

Except the merchant’s wall had a loose stone at its base. When Darien prised the stone aside—with both hands and a grunt, for it was heavy—there was an opening wide enough for each of them to fit through.

As Marlen brushed himself off with distaste, Darien surveyed their surroundings. Roses greeted them in a profusion that appeared white by moonlight, islands in a dark sea of thorns and leaves. A stone fountain plashed at the center, flanked by curving ornamental trees that were also in bloom. Stone benches were scattered under the trees with deliberate artlessness.

A rose caught Darien’s eye that was unlike the rest: in the night, it looked almost black. As blood would look by moonlight, Darien thought, and unsheathed his knife to cut it from the thorns.

“Let’s hope the merchant doesn’t notice the theft of his precious red rose,” said Marlen. “His only one.”

Darien smiled. Only an Academy graduate would be so metaphoric in his choice of words—alluding not just to the flower, but to its intended recipient. “Follow me,” he said. He wondered why he had felt compelled to share this experience with Marlen, who, though his closest friend, was unlikely to understand. But it was too late to reconsider. They approached the cherry tree where he and Rianna had assigned to meet.

“How long are we to wait?” Marlen asked. He spoke in undertone, though it was unlikely that his words would reach the house from this distance. That and the music of the fountain colluded to mask their voices.

Darien shook his head. “Why, did you have other plans tonight?”

“I might have.”

“It would do you good to practice ‘The Gentleman and His Love.’ I noticed you kept slipping up on one of the chords.”

Marlen flung back his hair. “I play it exactly as it ought to be played, Aldemoor,” he said. “You’d do well to practice not smirking when we sing it. The audience is not to know it is satire until well into the third verse.”

“I can’t help it that your bad playing amuses me,” said Darien. He grinned as he said it.

They passed the time amiably trading insults for what seemed quite a while before the door to the house opened, and a slim white figure appeared on the steps. The moon was silver on her long hair. And then she was running, dress and hair flowing behind her as she tripped into his waiting arms. She wore a nightdress, Darien saw, and was momentarily scandalized. But she couldn’t know, he reminded himself; there had been no mother to teach her.

“There you are,” he breathed into her hair. It was whisper-soft and smelled of jasmine, a summer scent. After a moment, he released her and presented the rose. She smiled, and even in moonlight he could see her flush. He knew Marlen would note this, and the chaste brevity of their embrace, and want an explanation. That part of it Darien didn’t want to tarnish with too much exposure to his friend’s mockery.

“Where can we go to talk?” he asked.

She looked down, her lower lip curling almost in a pout. “My father’s plans changed at the last moment. He’s home. Last I saw, he was even awake in his study.”

“Awake? Now?”

“There was—there was a murder tonight,” she said. “An associate of my father’s, in his own garden.”

“His garden?” Marlen said sharply. “That is strange.”

“You two have not been introduced—apologies,” said Darien. “Rianna Gelvan, meet Marlen Humbreleigh… thorn in my side since our Academy days.”

“Pleasure,” Marlen said lazily, and kissed her hand. Rianna looked startled, but nodded and drew back her hand, her composure a testament to her impeccable upbringing. Well, almost impeccable, thought Darien. With a high neck and long sleeves, she had no doubt thought her nightdress proper enough. The less proper implications were a nuance that had not penetrated the high walls of this garden.

Though it seemed a killer had managed to penetrate a different garden that same night.

Darien shook his head. Strange things happened in the capital. He had lived isolated on the Academy Isle too long, his only occasional respite the nearby village—and even that was against the rules. He and Marlen had since traveled to many towns and cities in the past year, but none compared in complexity or size to Tamryllin, the queen of them all.

“Do you think it will interfere with the Fair?” asked Rianna. Her eyes were round.

“The death of a merchant? Surely not,” said Darien. “Sounds to me like someone had a grievance against him.” He clasped her hand. “Don’t fret, love. The contest will happen. And Marlen and I are the best, and are sure to win.”

“Humility is not a trait in which we excel at the Academy,” drawled Marlen.

“Oh shut up,” said Darien and laughed. “No use denying the truth, is there?”

“All the same, there’s some stiff competition,” Marlen pointed out. “The contest brings the best people from all over the country. We know most of the people from the Academy, but there could still be surprises.”

“Like if Valanir Ocune were to participate,” Rianna said with sudden sparkle, and it was all Darien could do not to beam proudly. He flung his arm about her shoulders as if claiming a prize; when she leaned into him, he thought she felt fragile, like a bird.

“That would be unfair,” Marlen conceded. “Luckily, he is said to be wandering in Kahishi somewhere. Being the world’s greatest Seer must be a demanding job.”

“Didn’t he ever win the Silver Branch?” asked Rianna, her head on Darien’s shoulder.

“No… Valanir never entered the contest,” said Marlen. “Tales have it that he didn’t want the Branch, didn’t even want to become Court Poet. Of course, that may have been just sour grapes, since he and Court Poet Gerrard were rivals.”

Rianna shook her head. “I doubt the Seer Valanir Ocune has time for sour grapes,” she said reprovingly, as if he had uttered heresy.

Darien smiled. “You’d be surprised what even the greatest men have time for.”

“As our presence here at this hour would indicate,” Marlen said with a bow. “Listen, I want to get into the house and see the space where we’ll be performing at the ball.”

“But you’ve seen it,” said Darien. “We already performed there.”

“Yes, but I need to see it again,” said Marlen. “Any chance your father is asleep yet?”

“I don’t know,” said Rianna, confused. She leaned on Darien’s arm as if for support. “It seems… a risk.”

“So much the better,” said Marlen.

At last they agreed that Rianna would return to the house to see if her father and the servants were sleeping. And indeed, the silence within was absolute. To make certain she checked the study, and even ascended the stairs to confirm that her father’s bedroom door was closed.

“Thanks,” Marlen said when she returned. “I’ll be just a moment.”

Darien shook his head. “I don’t know when you became one of those poets,” he said. “The space, is it.”

“It matters,” said Marlen, and vanished into the house.

“Well that gives us a chance to be alone for a moment,” said Darien, and kissed Rianna’s cheek. “I only wish we were really alone—I would sing for you.”

“Soon?” she said, and rested her head on his chest. He was the first man she had loved, Darien realized, not for the first time. He was sometimes awed when he considered this. “You will at the ball, won’t you?” she said. “Even if no one knows it’s for me.”

“I will,” he said. “All my songs now are for you.”

* * *

Darien felt a silence come over him when Marlen returned, after he had clasped Rianna’s hand for the last time and watched her disappear into the house. In silence they crawled through the opening and into the alleyway.

It was only when they reached the streets near their inn that Marlen asked, a note of rare uncertainty in his voice, “So what’s different this time?”

Darien knew what he meant. So often had they helped each other in the game of seduction, seldom competing since their tastes were different. Marlen’s women tended to be unhappily in gilded marriages, dissatisfied as caged snakes. Darien gravitated to smiles, to laughter. But Rianna took him to a different place. Her eyes were still as the pools in the woodland of Academy Isle, and stirred within him a similar quietness.

“I think I love her,” he said, shaking his head. “A Galician girl.”

“Other than that,” said Marlen, dryly, “what’s the problem?”

“She’s promised to another,” said Darien. “One of much more impressive lineage than a youngest son of Aldemoor. And her father made mention of a winter wedding.”

“Sounds like you’ll need to move fast,” said Marlen. He looked unusually contemplative, gazing straight ahead, his long fingernail tracing the smooth carnelian stone set into his Academy ring. Perhaps that was why he did not ask Darien the obvious question: How could he be considering marriage? Darien, of all people? Only Marlen himself was worse suited for it. They had never made a formal pact, but both had assumed that the next ten years of their lives would be spent much as the previous one had been: traveling, singing, adventuring. Marriage meant one woman, one bed, one home.

But Darien thought he’d never wanted anything more in his life than he wanted Rianna Gelvan now. Even if it meant one home. Life with her could be an adventure, lit by the gold of her hair.

“If only we had those lost enchantments the Academy masters liked to go on about,” said Darien. “I could magic Rianna away from this place.”

Marlen laughed. “If we had powers, Darien, you could likely conjure up an ideal woman of your own.”

“A terrifying thought,” said Darien. “That could be a song—of a poet who uses enchantments to create his ideal woman, the havoc that ensues. There is always havoc—at least in songs—when you get your heart’s desire.”

“Is there?” said Marlen. “I’d risk it. Though it wouldn’t be some girl.”

Darien was only half-listening. “I’ll tell you what I need to do,” he said. “That Silver Branch is worth as much as a kingdom.”

“You think the merchant will approve your suit if we win?”

Darien wagged his finger at Marlen in mock reproof. “No, my Lord Humbreleigh,” he said with exaggerated courtesy. “When we win.”

Chapter 2

All her life, music was a secret. It was what you stole to the cellar at midnight or the deep pine woods to play, or sing. Verse was composed in greater secrecy still, by light of a single candle after dark. Even then, Lin had to hide the burned-out candle the next day, smuggle it out to the midden heap under cover of night.

But now music was a drinking song in a tavern performed to crowds of rough men, or more recently, a stately ballad sung to lords at their firesides. And tomorrow… tomorrow would be more than either of those things, much more.

In the humidity of the night, the streets were choked with the scents of summer flowers. Here in the capital of Tamryllin, music was like a dancer in the fullness of her youth wearing little to conceal her beauty, flaunting everything. To Lin, it seemed profligate to make something lush and voluptuous that was meant to be a mystery.

It was her northern upbringing, she knew; a chill she carried within her into this decadent and too-beautiful southern city. She had never expected to see it for herself. The imperial buildings by the water, glistening white as if polished a thousand times. The parade of art, from the gilded splendor of the king’s palace to the sculptures and frescoes that adorned even the humblest temples.

The white city by the sea, it was once named, in a song made long ago by Edrien Letrell himself. The great Seer had loved the capital. Now poets named Tamryllin “the White City” for Edrien, because of words spun one night by light of a single candle. Such was the capacity of one man to influence others, centuries after he himself had died.

“Tonight is important,” Leander was saying. He had dragged her into the tiny room they shared. “You can’t wear—that. We will need to buy you a dress. Perhaps on credit? I don’t know.”

Lin was grateful that he did not comment on the sorry state of her clothes. For the better part of a year she had been wearing the same shirts and trousers that she had stolen from her brother’s wardrobe.

“Leander,” she said in a calming tone, “I have a dress. Look.” She untied the bundle that lay on the bed they shared, shook free billowing folds of corn-colored silk. She stroked them with the back of her hand, and a rush of memory welled from the feel of the fabric, the bergamot scent that wisped in the air like smoke.

Leander looked awestruck. “I always said you were highly born.”

“You have,” she said. “An oversight on my part.”

“In your disguise?”

She ignored the question. “Did the approvals come in yet?”

Leander nodded. “I stopped by the office just now. The songs are approved—we can sing them tonight.”

“Good,” said Lin. “I wasn’t interested in recycling our old material. So we’ll meet back here in an hour to rehearse?”

“Why? Where are you going?”

“To get some air,” said Lin, and then almost laughed despite herself. Their inn was situated in the tanning district—the reason they could get a room to themselves—and the air was thick with the stench of the trade.

But her business took her away from the tanners, down an alleyway shortcut she had discovered weeks earlier. Only a month they had been living in Tamryllin, absorbing the atmosphere and excitement of the Midsummer Fair… and the contest. The last time it was held, Lin had been eleven years old and unaware of its existence. Nickon Gerrard, long established now as Court Poet to the king, had been green in power. It was difficult to imagine such a time.

Now she was at the heart of it all. This was the worst time of the year, the locals grumbled, but Lin could tell they were proud. At midsummer, thousands of merchants, traders, performers and artists from around the world converged upon the capital city. Spices and silks from Kahishi, wool from the northern hills, damask and jacquard from the southwest, jade and alabaster from the farthest east, where it was perilous to go… and through it all the wine would flow, or so Lin had been told.

The alleyway was a narrow passage that snaked between walls of stone. The windows in the walls began very high, and were dark holes. Down some narrow, winding stairs, she found herself at a square, where an ornate fountain graced the joining of three avenues. It was sculpted with the arcane symbols of the tanning guild. Here was where the district began, and by taking the street to her left, she was leaving it behind.

During one of her night walks around the city she had discovered a temple, but had never entered. But tonight she was to sing in the presence of the king and—even more unsettlingly—the Court Poet.

Lin entered through bronze doors and was met with a curtain of incense and candle fumes. She had expected the place to remind her of home, had in fact been steeling herself. But it was simpler than the chapel to which she was accustomed, and brighter, as if the southland sun could pass through stone. The marble sculptures of the Three were lit with a soft gold-toned light, not the bloodless white that she recalled.

An old woman wrapped in a shawl knelt before the statues, bent in prayer. She made no sound, and the room was still.

The Three gods: Estarre, Kiara, and Thalion; brother and sisters. Estarre terrifyingly beautiful, sword upraised in a gesture of salute or challenge. Thalion like a male version of her, a sword in one hand, but a huge book in the other, and an emblem of balance scales carved into his helmet. These things—the book, the scales—were what linked him with his other sister, Kiara. Chill-eyed, shrouded in robes. Her distaff held close, along with the secrets of the earthly world. She stood to the left of Thalion, Estarre to his right. There was significance in this, also.

Nearby, one of the candles had blown out in its sconce. A wisp of smoke danced a lazy spiral upward, vanishing before it could reach the mosaics that adorned vaulted ceilings far above.

Lin’s mother had worshipped Estarre to the exclusion of the other two, which—if anyone outside the family had known—could have meant a charge of heresy. But of course, no one would ever have told.

It was Kiara to whom Lin turned, as all poets did in Eivar. She lit a candle and set it down at the altar amid a sea of tiny flames. Each of them the same, as if all the dreams and desires of people were indistinguishable from one another. The prayer of a female poet, perhaps the only one in Eivar, no different from a mother’s prayer for her sickening infant or a farmer’s prayer for a good harvest.

Or in this particular part of the city, the prayer of a tanner. Lin smiled.

A brisk sound in the silence: footsteps behind her. Lin swung around. She recognized the poet who stood there—tall and darkhaired, an ironic smile perpetually tugging at the corner of his mouth as if he enjoyed a private joke. Or perhaps that was just when he saw her.

“Good day, Marlen Humbreleigh,” she said, softly so as not to disturb the woman who prayed.

“It’s you,” he said without lowering his voice. “Here to pay tribute to Kiara, I suppose.”

“It must be your perceptiveness that makes you such a successful poet.”

“Oh, I like that!” Marlen said, and laughed. “Like ice. Very good. Well if you must know, I’m here for the same purpose. We have a performance tonight.”

“As do we,” Lin said. “If you don’t mind, Marlen, I’d like to pray in silence.”

“We’re at the Gelvan ball,” said Marlen. “How about you?”

She sighed. “We are, as well.”

Marlen narrowed his eyes, his mask of indifference slipping for a moment. “How did a ragamuffin girl get that, I wonder.”

“The same way an arrogant, spoiled lord’s son does, I’ll wager,” said Lin, and heard, as if from far away, the cold anger of her mother in her own voice. It was always with her, a flame that she tried to hold in check under ice.

And what would Lin’s mother have made of this man? Lin thought she might know, but was not comfortable with the thought.

Meantime, Marlen had recovered his good humor, or at least the appearance of it. “I’ll be seeing you tonight then,” he said with a grin. “I can’t wait to see how you look in your best shirt and trousers, my dear.”

Lin knew Leander would be furious that she had “antagonized” this paragon of success in the poets’ world—for that was how he would see it. Turning away, she knelt before the statue, bent her head, and shut her eyes as if she were alone. It was easy to forget about Marlen once she had closed her eyes. The silence returned, marred only by the guttering of candles.

I want only to help you, the man had said. The lively flicker in his green eyes belying the silver in his hair, the creases in his face. On the third finger of his right hand a moon opal, one of the rarest of Academy rings. It was he who had somehow heard of Lin and Leander, an unlikely team considering that there were officially no female poets.

“Why would you help us?” Lin had asked. They were sitting in the common room of their inn, and she knew Leander was deathly embarrassed that Therron saw they were staying in such a place. But the Seer didn’t seem to notice the grime and noise. On his lips was a faint smile, as if he contemplated a memory that both amused and saddened him.

“There are flaws in the way things are done,” said Therron. His voice was deep. “One is that only a man may become a poet, and certainly only a man may become a Seer. You are brave to go against the tide. I would like to see that bravery rewarded.”

Now it was Lin’s turn to smile faintly. “Thank you,” she said, “but I am not brave. What I come from is far worse than anything I could choose. So in a way, I risk nothing now.”

“Even if you fail?” There was a dead weight to the question, contrasting with the din of the laborers who crowded at the other tables.

She met his eyes, strove to hold his gaze. “I will most likely fail.”

“You will if you allow no one to help you,” said Therron, taking her hand. “Take this invitation to the Gelvan ball. Make it the finest performance of your lives. The king will be there… and more important, so will the Court Poet. It may be the start of something for you.”

Lin looked down at their joined hands on the tabletop, and it occurred to her that he was not so old, and was fine-featured. And a Seer. “You have our thanks,” she said, and withdrew her hand—now holding a small parchment that she knew might be the key to their fortunes.

“Yes,” Leander echoed, starstruck. “Thank you.”

“It is with your best music that you will thank me,” said the Seer. Now Lin turned her mind from these thoughts, attempted to focus on prayer.

Kiara, she thought. Keeper of secrets. Help us make it our best.

She opened her eyes. The old woman had gone; so had Marlen. The polished floor beneath her knees had grown warm. Lin heaved to her feet, felt an ache in her shins and knees from being pressed so long against stone.

* * *

Marlen Humbreleigh considered returning to the shrine of Kiara to submit a prayer, but in the end decided that he did not care to after all. Let the dark goddess do her work as she saw fit. On the streets, he attracted no notice, just another poet among the hundreds who had thronged to Tamryllin for the Midsummer Fair. Once every twelve years they gathered here for the most prestigious of the contests, where the Silver Branch was won.

He passed a stand selling masks, with their hollow-eyed half faces. There were many such stands around the city these days, for the fair opened with a masque. Marlen thought it an amusing custom considering that in truth, everyone’s face was a mask.

Marlen had always been good at learning secrets. From the time he was tumbling his brothers out of apple trees in the family orchard— before they were allowed to be picking the fruit—bringing the ugliness of people’s deepest thoughts to light was… an amusement for him.

It came out in his work: critics praised Marlen and Darien for their masterful plumbing of the depths of human nature. At least half that contribution was made by Marlen, who felt the forces of his own need stir by candlelight, transform into the shadows of other, imaginary figures. He and Darien had risen to fame by subverting the heroes of bygone days. Making them human, and sometimes worse.

Some critics of their songs took a different tack, despairing that the popularity of these young poets and the men who imitated them bespoke a cynical age. Occasionally they even proposed that such songs be banned, but the humor of the poets’ satires was entertaining at court. At least, so Marlen had been told. As long as you did not mock the court itself, it was acceptable to satirize the heroes of old.

So much of the humor, he knew, came from Darien. Marlen was the shadow that danced in the periphery, sensed by critics who could not quite articulate the source of their dismay. That could be called a secret, too, he considered. The dark heart of their music.

But there was a difference between discovering a secret that could be turned into a song and one that mattered. One, for example, that could get someone killed.

Marlen had never discovered such a secret before the preceding night and now was not sure what to do.

It was Darien’s fault, of course, for sticking his nose—and rather more—where he had no business. A Galician girl, and on top of that, the daughter of one of the most prominent men in Tamryllin. Marlen knew there was no use pointing out his friend’s folly to him: Darien would do as he pleased. The world had long ago taught him that he could.

The lesson Marlen had learned was rather different.

And he really didn’t have time to be thinking of such things, not with the Gelvan ball coming up. To play before the king and even the Court Poet himself… He ought to have been with Darien right now, rehearsing. But spontaneity was one of the main characteristics of their partnership, and it was too late to change old habits. Even now, at this most critical junction of their lives.

The Gelvan ball. Back to the house where Marlen had gone to investigate the space where he and Darien would be performing. Where he could not resist doing a bit of exploring while he was at it—and thereby discovered the merchant’s secret, one that could cost the man his life.

That the Gelvan family was of Galician descent, at least on Master Gelvan’s side, was well-known. That Galicians loved money was also common knowledge, and undoubtedly how Rianna’s father had famously risen from street sweeper to become one of the most powerful men in Tamryllin.

But Marlen could now prove that Master Gelvan, trusted associate of the king, still worshipped the Unnamed God of the Galicians, an offense punishable by death. His careless exploration of the man’s study had uncovered a bronze shrine behind a concealing tapestry, along with a stack of books in the Galician tongue that had been banned in Eivar for centuries. The Galician religion accepted the existence of no other god—there was only One, they said. Which of course meant that they did not accept the existence of the Three, bless their names.

In the past thousand years, most Galicians had been converted by the sword, which meant that most were dead. Master Gelvan stood as an example of how a man might shuck off an inconvenient heritage and become great in the eyes of the king and court.

And now, it turned out, he was a heretic. And tonight Marlen would drink his wine, and smile, and sing for the man’s company.

It occurred to Marlen that he could not cease to think about this, to turn it over in his mind, because he was his father’s son.

Will you always be the shadow? Marlen could almost hear him ask.

And opened the door to the inn where he and Darien were staying, into the spill of light and warmth where there was no sign, none at all, that his life was about to change.

Chapter 3

Light assaulted her in the vast room; from overhanging lamps with their multiple slender branches, from torches in wall sconces of decorative brass, from wineglasses reflecting light like a thousand flashes of bared teeth. Master Gelvan’s house could rightly be called a palace, its parquet floors spread with intricate Kahishian carpets, wall hangings and paintings on the walls that Lin knew were each in their way special. Musicians played a teasingly frivolous, fashionable tune to which some were already dancing.

As Leander straightened his coat and glanced worriedly about them, Lin made her own calculations. The people who crowded the rooms were among the finest in the city. Added to that were contingents of foreign lords and merchants, here in Tamryllin for the week of the Midsummer Fair. Lin would have to be on her guard even more than usual. She didn’t think Rayen would accept the invitation of a Galician, even one so highly placed as Master Gelvan, but she couldn’t be sure. One advantage she had: with her hair hacked off and her body whittled to nothing, he was unlikely to recognize her right away. Nonetheless, tonight was a risk.

A flash in her mind’s eye and she was in a different room: a cavernous hall hung with draperies of finest velvet and brocade, with tapestries centuries old. Faces staring from them that possessed her forehead, her eyes. And Lin herself in the midst of a whirlpool of guests who stared and whispered and no doubt speculated on her stillunmarried state. Swirling in the shadows with hissing whispers, the guests reminded her of spirits. Her goblet of wine raised to her eye as if to consider its clarity and bouquet, when in fact it was so she would have something to look at… something that was not any of those measuring eyes.

See anything you like? Rayen, a warm feather of breath in her ear. Not that it matters, love.

And then she was back beside Leander in the home of a Tamryllin merchant, on the verge of performing before the Court Poet and king.

“Lin, what are you thinking?” Leander said out the side of his mouth. He kept tugging at the cuffs of his blue coat, which she knew was a nervous gesture.

“That I’ve already begun to itch.” It was true: so long had it been since she had worn a dress that her body now rebelled.

They had made the proper greeting to Master Gelvan where he stood by the entrance to greet guests, framed beneath an arch of fluted marble. He was a slender, tired-looking man with pale hair verging toward grey. His attire was scarlet, slashed with gold-threaded brocade. She could imagine the cost of obtaining that color. A ruby pendant on a chain rested on the merchant’s chest, a plain gold ring on his left hand—though she knew his wife had been gone many years. He had acknowledged Lin and Leander with a nod, without indicating surprise at a female poet. She was grateful for that.

Now surveying the crowds, Lin said, “Oh, dear.”

Leander jumped. Everything before a performance made him anxious. “What?”

She had caught sight of two black-clad men, impeccably groomed and indisputably handsome. Each wore an ornate harp strapped at his waist on a tooled leather baldric. “Them.”

Following her gaze, Leander swore under his breath. Lin sighed. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I knew they would be here. I met Marlen today in the temple, and he told me. Quite pleased with himself, of course, though that is probably his permanent state of mind.”

They made a striking pair: Marlen tall and brooding, Darien slender and blond, with those mischievous blue eyes. Both were the most celebrated poets of their year at the Academy, and possibly of the decade. In just a year out of the Academy, they had made a name even some Seers might have envied.

And who might compete with them? Lin thought. A female poet of little training? An Academy graduate who had, thus far, failed to make a mark?

She knew what her partner was thinking. “Leander, listen to me,” she said. “Therron sent us here because he believed we have talent. A Seer sent us. We don’t have to be intimidated by these men.”

“They’re better than we are,” he said. “And they have two harps, which means they can do the more complicated duets. Where’s the wine?”

She caught his arm in a way that she hoped was inconspicuous. They could not be seen to quarrel, not here. “You know what happens to your concentration when you drink,” she said. “We can’t afford any wrong notes tonight.”

“You’ll deny me wine from Master Gelvan’s cellar after months of cheap ale?” said Leander. “Lin, where is your heart?”

She smiled, relieved that his good humor was returning. “Afterward,” she said. “To celebrate a song well played.”

And when that time came, she thought, she could do with a glass of wine herself. Pale gold from the mountain vineyards and poured to the brim, in the style of a northern man (or woman). The heat of summer hung upon them here, but she still was who she was.

Strains of a new piece of music were beginning, this one even more tinkling and lighthearted than the last. The musicians played on fiddles, tabors, and lutes, instruments of the moment. The merchant was nothing if not fashionable.

Avoiding eye contact with any of the guests, Lin saw that someone else had joined Master Gelvan under the arch: a stunning girl, gowned in emerald green. Her golden hair had been curled elaborately and then allowed to cascade from a hairpin crusted with diamonds.

That would be Master Gelvan’s daughter, without any doubt.

The merchant had many treasures, but Lin thought, seeing Rianna Gelvan, it was apparent which was most dear.

Leander had left her side, off to seek wine against her wishes, or perhaps only women. He labored under the misapprehension that a poet’s ring was all that was needed to make him an attractive prospect—that and his family’s estate in a green valley to the southwest. Like many southern men, she thought, he had an exaggeratedly optimistic view of the world. A name for Tamryllin in more sentimental songs was “City of Dreams,” but it seemed to Lin that dreams were just as likely to be killed here as they were to come alive.

Still, it was to this city that she had come, from dark forests and cold. Nothing else could frighten her now. And then Lin felt a shiver, smiled a little, at the bravado she knew was false.

In that moment she spotted the Seer Therron in an alcove to the side, out of sight of most of the guests. Their eyes met and he smiled, and it occurred to Lin that he might have been watching her.

No fear, Lin told herself, and moved to join him.

* * *

She watched him. As those around her sipped wine or chatted in sedate groups, Rianna kept her eye on Callum. Clad in his best jacket, he was pacing the room with a decanter of red wine, filling glasses for the guests. But at the very start, she noticed that after filling the glass of a particular guest—a middle-aged woman Rianna did not recognize—Callum had pocketed a note.

An itemized note on the body had his name, he had told Master Gelvan.

Her eyes narrowed, Rianna almost didn’t notice Ned until he was nearly knocking into her. “What?” she snapped. “Oh, sorry. Really, Ned, I’m sorry.” It had been his clumsiness, but she knew that was something he was just about helpless to control, long limbs getting away from him.

“What is it that has you so occupied?” he asked with a strained smile. Rianna sensed the hurt behind that smile, regretted that she had lost patience even for a moment. He deserved better from her. If she was going to elope with a poet instead of marrying Ned Alterra, she could at least be kind.

“What do you know of Master Beylint’s murder?” she said, leaning forward so only he would hear.

His brow furrowed. “That’s not something I’d expect you to be curious about.”

“Why not?” she said. “He’s a friend of my father’s, or rather he was.”

“It’s a terrible thing,” said Ned. “The Beylint family was supposed to attend tonight, but now of course they are not. My father donated for an elegy at the Eldest Sanctuary… I’m sure yours did as well.”

“But Ned, what do you think is going on?” said Rianna. “Don’t you think it’s strange that he was killed exactly like those poor people in the streets?”

Ned shrugged. “Could be some sort of imitation. I don’t know, Rianna. I hadn’t thought about it, I admit.” He ran a hand through his hair, a nervous habit that never failed to make it stand on end. “I didn’t exactly come here to talk about a murder. I thought… I was wondering… would you like to dance?”

Then she saw it happen: Callum approached Master Gelvan, refilled his glass. And in a movement so quick it was almost sleight of hand, the note found its way to her father’s pocket. Rianna drew a sharp breath.

“What is it?” said Ned.

“Nothing,” said Rianna. She forced a smile. “Of course we must dance.”

* * *

Darien noticed that Marlen was already working his way through a second cup of wine. It was unusual for him to do that before a performance. Though Marlen did pride himself on his ability to do anything while inebriated… and if women were to be believed, he did mean anything.

“I suppose you miss Marilla,” Darien said acidly. “Why didn’t you bring her?”

Marlen barked a laugh. “I’m not yet important enough to bring my whore to events like this. Besides, she’d probably try to seduce whomever she believed the most powerful man in the room. It would be embarrassing.” He drained the rest of his glass. “This wine’s foul.”

Darien watched him narrowly. He’d begun to wonder if Marlen’s taste of life in the capital had somehow… changed him. Talk of Marilla brought out a savagery in him that Darien had seen rarely in the years they’d been friends.

And women must come second, always, to the music. In more ways than one, one of Darien’s lovers had once wryly observed.

He could not imagine Rianna saying such things, ever. It was at once wrenching and gratifying to be able to watch her from across the room, without—of course—ever daring to approach. But from a distance he was free to observe her gleaming like a jewel by light of the overhanging lamps. And then at her side—a lank interloper—there was the suitor. Rianna had told Darien his name, but he had stubbornly forgotten it, willed it into nonexistence. And in truth, the man looked almost nonexistent anyway.

“Before you get to thinking that I’m too wrapped up in my wench, you ought to see how you’re ogling that child,” said Marlen, startling him. “And not that it’s your business, but I haven’t seen Marilla in nearly a month.”

“It’s not my business,” Darien said curtly. “And Rianna’s no child. For the love of Thalion, she’s about to marry that stick over there.”

“Him?” Marlen raised an eyebrow, amused. “My. He must have money, or title. Something… not apparent to the eye.”

Darien was about to reply when he noticed that a hush was overtaking the room: the music had stopped, the chatter all but ceased. Twelve men in the red and black livery of the palace had entered, each bearing a horn.

The Ladybirds, as Darien and his friends referred to the king’s guards derisively. There to enforce laws like the approval of songs for their content and form, and the proper mode of bowing when addressing his majesty. Such men may as well split open and fly away, for all the respect they deserved. But as Marlen once pointed out, they did know how to use weapons. And poets who failed to get their songs approved ended up imprisoned, or worse.

Darien had seen King Harald only once, and Court Poet Gerrard only twice. It was an unspeakable honor that they had arrived here tonight, at the Midsummer Ball of a merchant. But Darien knew Master Gelvan was not merely a merchant: he had cultivated the king’s favor, using his extensive resources for the greater glory of the monarchy. Of course, Galicians were skilled at that sort of thing.

Six men stood at attention on each side of an unrolled carpet, and in unison their long brass horns were uplifted and sang. Across the carpet, the king and queen progressed arm in arm at a majestic pace, allowing the surrounding crowds to pay homage with downcast glances and bended knee.

Clad in a ceremonial mantle of porphyry, the king was round and soft, as was the queen at his side. Harald and Kora had produced an heir as round and soft as themselves, a boy who was now twelve and rumored to be afraid of the dark and dogs. When Darien was a child, he had heard talk among the adults of the dwindling of the Tamryllin monarchy; Harald’s father, a great ruler, had been felled by a sudden illness. Leaving only one, unimpressive son.

At the Academy, the students had often traded banter back and forth about the ineffectual monarch, though the more clever ones realized that that same monarch might be their avenue to success.

It was the figure coming up behind the king and his entourage that drew the eye much more: Nickon Gerrard, Court Poet and the king’s favorite. Drifting from his shoulders the six-colored cloak that only he was permitted to wear. A handsome man who had aged gracefully, with a distinguished profile and only a touch of silver at the temples. His eyes sharp and clever, as if there was nothing that could evade his gaze.

Harald depended upon him for everything, it was said.

The music was starting up again. Master Gelvan lifted his arms as if to encompass the entire room and all the glittering people there and called for a dance.

Normally, Darien would have used this as an opportunity for flirtation. Now, knowing that Rianna was here and not with him, he hung back. It was then that he caught sight of a slight woman in corn-colored silk, her head covered with a silk cap set with a single pearl. Her face was all eyes, large and deep-set in a sharp, pale face. She looked oddly familiar. He recognized the man who accompanied her easily enough, for he was just a year ahead of them at the Academy.

“Marlen,” he said, “who is that waif with Leander?”

His friend smiled. There was wine in his glass again, as if by magic. His eyes were glazed and a bit pink. “Picture her in a man’s trousers and shirt, and you’ll remember,” said Marlen. “She’s our competition tonight. It’s a bit offensive, don’t you think?”

“I wasn’t aware it was a competition,” said Darien. He was growing weary of his friend’s mood and wished to be elsewhere. Such as, across the room offering a cup of scarlet wine to a girl in a green dress. And if he could not help but see the symbolism in that, then so be it.

The music must come first, he reminded himself. Rianna Gelvan was here, but so were the king and his retinue… and Nickon Gerrard.

Remembering that moment later, Darien would think, somewhat ruefully, that if he had known then who else was in the room that night, it would have eclipsed those names altogether. And likewise if he had known what was to come in the next hour, not long after the moon had crested the nearby sea.

* * *

The green he wore matched his eyes, Lin noticed as she approached Therron. Nearby, a group of what appeared to be Kahishian nobility, dark-skinned and clad in shades of red and violet and yellow, were conferring in their own tongue. She had never seen any of the desert people until now. They were of course here for the Fair and the worldfamous contest.

“Erisen,” she said with a small bow. “I didn’t expect the honor of seeing you again.” And then she caught sight of the harp at his hip, saw it was of gold and that the strings were gold. A wave of longing swept through Lin, the like of which she had not thought to feel again.

She met Therron’s eyes and wondered if he had seen that look of longing, for surely she could not have concealed it in time. “The light of lamps and the songs of the hearth still call to me,” he quoted. “How could I have stayed away?”

She saw that he had no wine. “Will you be singing for us?”

“I believe so. Right now, though, I am admiring this painting.”

Lin moved to stand beside him. Master Gelvan had a number of paintings and tapestries hanging in this room. This painting depicted a grey-haired man with a harp, surrounded by mountains, under a black sky where hung a full moon. Brightness emanated from the poet as if from his skin. In contrast, the mountains were nearly as black as the sky. The stone of the poet’s ring gleamed like a second moon.

“Edrien Letrell,” said Lin. “Of course. Sometimes I think everyone has a painting of him.”

Therron smiled. “True, though this is finer than most. Edrien Letrell’s search for the Path is a popular story, not just among poets.”

“Perhaps because he returned triumphant,” said Lin. “People like stories with an uplifting ending, or at least they did.”

“We do seem to live in a time when nobility is often questioned— even mocked,” said Therron. “Yet somehow the tale of Edrien endures.”

Edrien Letrell, greatest Seer of his age. In the distant past, he had sought the Path to the Otherworld that for so long had been relegated to myth, was thought lost along with the enchantments. And he had returned refusing to tell of what he had seen—bringing only the enchanted Silver Branch from that realm as proof. Poets told of its ethereal shining, how each spring the branch blossomed with flowers and leaves that were lost again in winter. The branch awarded at the contest every twelve years was only a replica of the enchanted Silver Branch now housed within the Academy’s Hall of Harps.

In Academy culture, Edrien Letrell was revered. He had occupied a similar space in his age as Valanir Ocune did in her own—was even more highly regarded, since he had found the Path. The poet who had told her of these things had done so with a mix of wistfulness and resentment. There seemed no end in the Academy to the measuring, the competition. Or so it seemed to her, observing from outside.

“We need such stories,” said Therron. “I believe in the coming days, we will need them more and more.”

Lin shifted her gaze to the Seer. He was still eyeing the figure of Edrien, and appeared lost in thought. The sounds of the ball washed over them: the tinkle of a woman’s laugh, the measured patter of talk.

Suddenly, the call of trumpets: it had to be the king and his retinue arriving. Lin was momentarily grateful for the concealment of the alcove.

In that time the Seer hadn’t moved.

“The king and Court Poet are here,” Lin said to his profile. His nose was the slightest bit beaky, his eyes deep-set in shadow. “I suppose you have met them.”

“Oh yes,” said Therron, absently. “Many times.”

She waited, but still he contemplated the art before him as if nothing else existed. At last Lin said, “I don’t understand. What do you mean, we will need these stories?” Behind them the music started up again, this time a slower dance.

Now Therron did look at her, his expression seeming to shift in the lamplight from stern to tolerant and back again. She couldn’t tell if he truly wanted to be speaking with her or wished for her to be off. She was about to do the latter when he said, “I’m going to the garden to tune my harp. Would you care to join me there?”

He offered her his arm, as a gentleman might a lady. She nearly laughed, though could not have said why. Instead, she wordlessly took his arm, allowed him to guide her to the tall doors that led to the garden and then out, into the midsummer night.

Chapter 4

Deception could so quickly become a part of one’s life, Rianna thought as she allowed Ned to lead her in a dance. In truth, Rianna was the one who was leading—another deception, long-practiced, and for his sake. The charade had never seemed irksome until tonight. She had begun to wonder what it would be like if just once, she could allow someone else to take the lead.

He was looking into her face very earnestly, as if searching it for clues. He had a habit of doing that—had been doing it for all the years she had known him, which was most of her life. But now that her father was beginning to talk of a winter wedding, of making their troth official, Ned had begun to do it rather more.

Rianna forced herself to meet his eyes. So often they had confided in each other, growing up. Ned the man was not much different from Ned the boy—serious, overly lank, clumsy. He had proved strangely resistant to the lessons ingrained in most of the nobility—in physical grace, in arrogance.

Rianna forced a smile. “Why so quiet?” she said. She dipped in his arms and allowed him to twirl her around, seemingly without effort. Her hand clasped his shoulder, lightly. His hand at her waist was a familiar presence; they had danced together thus since she had come of age.

Ned shook his head. “I think you know why, Rianna.”

The blood rose to her temples, pulsing in her ears. If even one of the maids had spoken with another servant, with anyone… “I don’t,” she said, with what she hoped was a puzzled expression. And hated the necessity of wearing an expression with him as if it were a mask.

Ned sighed. She could not help but notice that he always looked awkward in his elegant clothes, as if they had somehow been fitted wrong. “I know you don’t love me, Rianna,” he said. “I know this marriage was not your choice… any more than it was mine.”

“Well…” Her heart had slowed somewhat, but she still wasn’t sure how to deal with this. The light melody the musicians played grated in her ears, a dissonant mockery of what she was feeling.

“I only hope that…” Ned bit his lip. “I hope in time you may come to love me. Even if it is not as I love you. I know I don’t deserve you, Rianna.”

It was too much, Rianna thought, and the dance was not sufficiently distracting. They turned together, facing the crowd of onlookers who were probably speculating about them right now. She had heard the whispers. That her Galician father had made use of her beauty to ensnare a lord’s son.

How could these people ever grasp the truth: that she and Ned had known each other since they were children and that their friendship had led both their parents to speculate about it becoming something more? Her father did not need more gold—she was certain of that. What he wanted, she thought, was the stature that would come with Ned’s family name. And she could hardly blame him—once a street sweeper—for wanting that.

“Ned, I love you as a friend—even as family,” she said truthfully, in as low a voice as the music would allow. “I always have. You are right, though, that a marriage between us feels—strange to me. That it might not have been my choice.”

He may have flinched a little. “I am sorry,” he said. “Do you think, though, that I could still make you happy?”

Rianna thought her heart might burst. “It’s very possible.”

She had no choice, she reminded herself. Darien had assured her that he would devise a plan—but there was no plan that could spare Ned the betrayal that was to come.

Rianna had heard there were kingdoms, oceans distant, where men and women could marry of their own free will. Such a place would be far away, Rianna thought. Beyond the green hills and lakes of Eivar, over the expanse of desert and mountains of Kahishi, across the Blood Sea and the lands of the farthest east. Places she would never see.

Over Ned’s shoulder she caught sight of Darien across the room with Marlen at his side and an ironic smile on his face. He was so much the opposite of anyone she had known in her life. Tonight, she would hear him sing.

* * *

It was quiet in the garden. Though a few couples had escaped into the evening and now whispered among the roses, most of the merchant’s guests preferred to be where the music and wine were flowing.

Twilight was descending as Lin and Therron seated themselves on a bench in silence. Without a word, the Seer fell to tuning the gold strings of his harp. Lin felt a pang of something less pleasant now than longing. She thought it was unlikely, unless she killed someone, that such a harp could ever be hers.

There was another thought nagging behind that one, but she could not quite catch it. At the sound of his voice, melodious like no other voice she had heard.

“It was brave of you to come here tonight,” he said, his eyes still on the strings, sharp nails plucking. The sounds like fading bells in the dusk. “To be introduced as a poet, with the king and the Court Poet present.”

A gentle wind rustled the trees, stirring the scent of roses in the air. Lin shrugged. “We obtained approvals for the song. There are no laws about the sex of the person who sings them.”

“True.” Now he did look at her, and smile. “You could have been a lawyer, spared yourself such a flimsy profession as this.”

“So instead of a female poet, a female lawyer?” She raised an eyebrow. “An oddity, either way.”

He laughed. “Lin,” he said, “who are you, really?”

And it was then that moonlight broke through the clouds, touched Therron’s face. And like an enchantment—for so it surely was—the light picked out iridescent symbols in Therron’s skin, radiating from his right eye. Lin recognized them as ancient runes—intricate lines that shimmered in the night, reflecting the light of the moon.

It was the last of the enchantments still in use at the Academy: the marking of a Seer. None but Seers knew how the mark was made. The rite was secret. Certainly the young poet who had taught Lin all she knew had been as much in the dark as anyone.

The moon illuminated something else, too: the moon opal on Therron’s right hand, which shone with a pale flame. The thought that had been drifting at the back of Lin’s mind returned, and this time she recognized it. She felt the blood drain from her face.

“I could ask you the same thing,” she said, keeping her tone even.

He inclined his head to acknowledge her thrust, as if in a duel. “What gave it away?” he asked. “The ring?”

“That,” she said, “and that I have never heard of any Seer by the name of Therron. Yet clearly you are a master whose name would be known.”

Now he smiled, glittering cold. He seemed to be distant now, withdrawing. “I thank you.”

Though it was dark, the mark surrounding his eye shone like a star fallen to earth. No, Lin thought, that was too hackneyed a phrase. Yet there it was. Light and laughter from the party drifted toward them through the wrought-iron doors, reminding Lin that she was to sing tonight. As was he.

Into the silence he said, in a different tone, “As I recall, you had a question for me. About our need for the tale of Edrien, in the days to come.”

Lin shook her head helplessly. “Well,” she said, still overcome.

His eyes looked very green. “Word has reached me,” he said, “that the Red Death is in Sarmanca.”

She inhaled sharply. The plague that had supposedly been key to the undoing of the great Davyd Dreamweaver, the last Seer to possess enchantments. Hundreds of years ago. But these were legends. Lin shook her head. “It’s practically a child’s tale.”

“Tell that to the people of Sarmanca,” said the Seer, but gently. Before she could speak again, he took her hand in his. “Reports have reached me—so far over a hundred dead.”

“Why is no one else speaking of this?” Lin demanded. “All those people inside—do they know?” Sarmanca was far southeast, near the mountains that bordered Kahishi. Rayen had told of trees bearing red perfumed flowers the size of his head, their velvet petals carpeting the ground come summer.

“The truth about Sarmanca—and many other things—has been hidden from all of us,” said the Seer. “Listen: the plague will not remain in the south. It will spread, reach Tamryllin, and at last the north until all of Eivar is stricken.”

“So you’re saying we are lost?”

His tone was stern now. “I am asking that you recall what it seems all poets have let themselves forget—that the true purpose of our art is not to perform at parties, nor to win contests.”

“Our true purpose?” Lin met his gaze. The familiar anger sparked in her. “Look at me. If my purpose was to earn gold, or praise, Erisen, I would not be here.”

For a moment the Seer looked surprised. Then he laughed. “Of course,” he said. “You are right, Lin. I’m sorry—you are right. And that reminds me.” He twisted off his Academy ring and, before she could react, was pressing it into her hand. “For safekeeping,” he said. “Will you do that for me?”

“Why…”

“You might say it’s a—precaution,” he said. “Now come. We’d best go inside.”

Lin stared at him, at the shadow his face had become in the dark, at the light over his right eye. “One question, then,” she said. “Why did you deceive us?”

“I’ve enjoyed our meetings,” he said. “Did you?”

Caught off guard, Lin nodded.

“Then take that with you,” he said, “and try to think well of me.” And then he was standing, brushing himself off, and standing taller than she had noticed before, the harp again strapped to his side. The glow of the mark seemed to spread to the rest of him, as if he were in his entirety illuminated, but she knew that was a trick of her imagination.

Lin felt a sense of loss without knowing why as she watched the Seer bow and then turn to rejoin the crowds. As he entered the sharp line of light from the garden doors, she saw a slight stoop in his walk but knew it did not matter—would not matter to anyone in that room, who would surely tell of this night for the rest of their lives.

* * *

Darien had told Rianna that there were no female poets, but that didn’t explain the woman who stood at the center of the room and sang as her companion strummed a harp. Her sharp face was upturned to the lamplight, her eyes focused somewhere past them, past all the people there. The voice that rose from her frail frame was surprisingly powerful. It was a song of lost love.

Darien had sung a love song, too, a masculine rendition that Rianna was certain he had written for her. Marlen had stood at a respectful distance behind him, contributing only melodies with the harp and his voice. The words still echoed in her head:

Snow Queen of my heart

a dark night slowly falls a

nd if I lose you in shadow

I will ever sing alone.

His eyes had never met hers, but the music strummed her bones as if she were a harp, or her nerves were the strings. She was by now expert at keeping her face impassive.

Now this poet, Lin—she gave no other name—was singing, with her strong voice and the dress that was too big for her. The song was wistful, as if it were sung by an older woman looking back from the end of life. It brought tears to Rianna’s eyes, though those had probably not been far off.

At the conclusion of her song, Lin was met with silence—and then, slowly, a flurry of gracious applause that almost immediately petered out, like a brief drizzle of rain. It occurred to Rianna that while she was fascinated by the idea of a female poet, others in that room might feel differently.

Lin and her partner took a graceful bow. Rianna’s father came forward to shake their hands, then announced, “Thanks to all our esteemed performers—and good luck in the contest!”

More clapping, just as controlled as before. Rianna felt proud of her father, for he cut a fine figure tonight, and she knew many women were watching. She had decided that her best course was simply to ask him about his and Callum’s strange behavior. No doubt there was a reasonable explanation.

Likely she had occupied herself with the business of Master Beylint so she would be distracted from her own deception, and Ned.

“Now for a surprise,” Master Gelvan was saying. “We have here a guest of honor, returned from long travels abroad, who has agreed to sing for us tonight. Words cannot express how deeply honored we are to have him with us in our home. I present to you Eivar’s greatest Seer—the one and only Valanir Ocune.”

A greying man in green came forward with a bow to Master Gelvan. Rianna barely had time to register her shock—both that the great man was here, after so many years abroad, and that her father had concealed the fact from her. More secrets, she thought. She looked at Ned and saw that he was grinning. When their eyes met, they both nearly laughed aloud. How often had they talked of their longing to see Valanir Ocune perform, just once? And now, without any warning, he was here.

Yet as Valanir Ocune unslung his harp and adjusted the instrument in his arms, the applause that greeted him was just as measured and careful as before. Rianna wondered why.

* * *

“The old bastard,” Marlen muttered. “So he’s back.”

“That old bastard is only one of the most famous men in the world,” Darien said dryly. He was feeling pleasantly warmed by the success of their performance, however weak the applause had been. A strange aura hung about the room tonight.

And now Valanir Ocune was here. It wasn’t fair—it was just the sort of thing that could eclipse their hard work altogether—but Darien was pleased that he would get to hear the master perform. During Darien’s years at the Academy, Valanir had been little more than a legend to the students. For more than a decade he wandered in foreign lands… performing for the sultan of Kahishi, it was said; vanishing for months at a time into the desert.

“Yes, but…” Marlen’s color was high, and he spoke with a rare excitement. “Valanir Ocune and Court Poet Gerrard are rivals. Sworn enemies. And both here.”

Darien thought that was a little dramatic, but didn’t have a chance to say so: a hush was flooding the room. Valanir, eyes alight, had begun to speak.

“It is good to be home.” Each word, shaped with the precision of a rock carving, falling into a breathless silence. “This will be my first performance on this side of the mountain pass. The first, and perhaps my last. Who can say?”

Darien raised an eyebrow. He and Marlen exchanged glances. His last?

“I give thanks to Master Gelvan for hosting me here tonight,” Valanir went on. “Here in this graceful home, which has so much of Tamryllin in it. The art, the music… and tonight, royalty and the Court Poet himself.”

Inevitably, many guests’ eyes shifted to observe the king and queen, the Court Poet beside them. Nickon Gerrard’s face carefully expressionless.

“I wrote this song imagining the roses and the sea winds of Tamryllin, as I took shelter in a tent in the eastern mountains during the journey from Kahishi,” said Valanir Ocune. He had begun to strum his harp, lightly, softly. “This song,” he said, “is dedicated to my home.”

* * *

“Did you know?” Leander hissed in her ear.