Since leaving his homeland, the earthbound demigod Demane has been labeled a sorcerer. With his ancestors’ artifacts in hand, the Sorcerer follows the Captain, a beautiful man with song for a voice and hair that drinks the sunlight.

The two of them are the descendants of the gods who abandoned the Earth for Heaven, and they will need all the gifts those divine ancestors left to them to keep their caravan brothers alive. The one safe road between the northern oasis and southern kingdom is stalked by a necromantic terror. Demane may have to master his wild powers and trade humanity for godhood if he is to keep his brothers and his beloved captain alive.

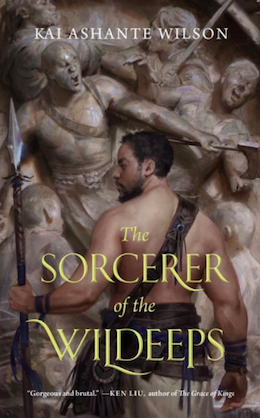

Critically acclaimed author Kai Ashante Wilson makes his commercial debut with The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps, a striking, wondrous tale of gods and mortals, magic and steel, and life and death that will reshape how you look at sword and sorcery. Available in paperback, ebook, and audio format September 1st from Tor.com! Warning: This excerpt contains explicit language.

The merchants and burdened camels went on ahead into the Station at Mother of Waters. The guardsmen waited outside. Tufts of rough grass broke from the parched earth, nothing else green nearby. Demane squinted at the oasis. Palm trees and lush growth surrounded the lake, dazzle reflecting from the steely surface. Just look at her, Mother of Waters; was anything in the world more beautiful—?

“Sorcerer,” said the captain, tapping Demane’s arm. He got out of the way. Tall and thin, Captain escorted the caravanmaster to the front of the gathered brothers.

Earthy and round, the little man hopped up on a rock. “Your choices, gentlemen.” Master Suresh l’Merqerim broke it down for them: “Leave us; and join some other group of saltmen going straight back north. Do so, and you go home beggars. Three silver half-weights are what you’ll get from me, and not a whoring penny more. But permit me to ask: Who here has balls? That man I invite to press on with us! Hard men will be required on the road down past Mother of Waters, when we come to the Wildeeps, and later reach the wide prairies north of the great lady herself, Olorum City. Such men of courage as are among you, they shall know a rich reward once we arrive in Olorum. Loot, and more loot, I say! A whole Goddamned fistful of silver full-weight coins. In Olorum, I shall open up a heavy bag. You will stick a greedy hand down into it, and grab out just as much silver as one fat filthy fist can hold.”

Nor had the caravanmaster quite finished. “We stay in Mother of Waters only for one night: tonight. Tomorrow dawn, this caravan hits the fucking road again.” Suresh really could stand to slow down on the cussing. While it was true that most brothers showed purer descent from that half of the mulatto north supposedly more blessed with brawn than brains, and for the merchants it was the other way around—brighter of complexion (and intellect?)—did it necessarily follow that one group deserved fine speech, while the other should get nasty words sprinkled on every single sentence? “You motherfuckers came here on our coin, our camels. And while you lot drink and whore tonight, we merchants must sell the salt, must empty the warehouses, must pack the goods, must swap the camels for burros. Therefore—right now—I need numbers for how many mean to press on with us. Tell Captain Isa your choice: you brave, you venturesome, you men who are men. And may God bless the cowardly cocksuckers we leave behind.”

The caravanmaster hopped down. From a sack, he handed out fragments of a slab-of-salt that had broken in transit. Plentiful chunks, which brothers could trade in the Station for room, board, and vice, went around. On his one free night, Demane wanted only to spend what a later age would call “quality time,” not to run around Mother of Waters rescuing fools from folly. But even leaving aside those brothers intent on browsing the black market or the prefelonious with contraband themselves to fence, the very wisest plans Demane heard his brothers making were nothing of the kind. You had wantons looking forward to boughten love, tipplers to some beverage called “that Demon,” gamblers to the local bloodsports… The guardsmen grinned and said Thanky as their cupped hands were filled to brimming. Much could be said of Master Suresh, and not all to his credit; but he wasn’t stingy. Bag empty, all the brothers’ hands full, the caravanmaster headed off for the Station.

“Y’all do what you want,” said Mosteyfa called Teef. “But this nigga here?” They called him that for the obvious reason: long, snaggled, missing… “Is going all the way to Olorum.”… pewter-black, moss-green, yellow… “My ass ain’t tryna go right back up to the desert.”… cracked, carious, crooked. “A nigga need some rest behind that motherfucker!”

Demane felt much the same, crudity notwithstanding. A unanimous rumble rolled across the gathering of brothers.

“Anyone?” said the captain. His right hand pantomimed a man walking away, left hand waving goodbye.

“Come this far,” said some brother, “might as well go on.”

“I ain’t never seen Olorum, noway,” said another brother.

“Silver full-boys, y’all!” said a third. “Much as we can grab, y’all!”

Captain cupped one eloquent hand behind an ear, his other urging brothers to speak up now. There could be no change of mind later.

Nobody said anything.

So the captain pointed off the route to the Station—to a field of cropped stubble and petrified goat dung. “Drills,” he said. “Throwing.”

The brothers groaned. They complained. The two words sufficed, however, for them to drop their packs and scramble to join Captain—already run out ahead of them onto the field and waiting. The brothers shaped up like ducklings, all in a row with their spears.

Demane tossed a couple packs off the trail to the Station, over with the other baggage. Lately wounded, Faedou eased himself down, gripping his spear like a cane. He leaned back against the piled packs, good leg bent, trick leg outstretched. Around the back of his head some gray naps grew still, his bald pate shining like volcanic glass.

Looming against the light, Demane stayed afoot as though to see drills better. His broad stature cast commensurate shade down over his brother, seated. Sweating too much, breathing too loud, Faedou kept his face hardened against pain. The odor of infected humors coming off that bad leg stank such that Demane’s sensitive tongue could taste the bacterial action in stagnant blood.

“You oughta let me take a quick look-see,” Demane said, not for the first time. “I won’t even touch my bag unless you say so. Promise.”

“I told you, Sorcerer.” Faedou threw an edgy glance up at Demane’s bag. “I put my hopes in God.”

After that last clash with bandits, Demane had tended the injuries of all the brothers save for Faedou, who, it seemed, feared the pollution of heathen arts even more than death by gangrene.

[Saprogenic possession], [antibiotic exorcism], the perils of [sepsis and necrotizing tissues]… Demane had perhaps doomed Faedou, in speaking such terms without knowing them in a common language. To superstitious ears, nothing distinguished those untranslated words from the veriest babble of demon worship. “If that leg get too bad, old man, the only thing will save you is chopping it off.”

Faedou rocked side to side. “Prayer and trust in Him. His justice and mercy: that’s all I need. Maybe I’ll wade in the Blood of the River soon. That’s all right. I asked the Dove to come down to my shoulder long ago. Won’t you ask Him too, brother? For it’s said in the Recital of Life and Days—”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah!”

You had to catch them quick—these more religious northerners—or they’d go on that way for a while. Why not get the old man talking about something useful? Nobody except the captain had crisscrossed this quarter of the continent more than Faedou. And so Demane asked about the Wildeeps.

“A strange place, nowhere else like it. Rains a lot down there, but you get sick of it after the first couple days…”

Demane listened, keeping an eye on drills. No matter how often he’d seen the captain’s reckless feats of speed and skill, every time was still astonishing. Captain ran far out or in close, depending on the strength of a given brother’s throwing arm. One at a time, they cast spears at him, aimed to kill. He either batted the spear aside or snatched it from the air, and dropped it to the dust. “Foul,” he called or, if some rare effort merited encouragement, “Not bad.” A brother ran to fetch his spear only after Captain had passed three men further down the line.

“Wildeeps must be far away,” Demane said. “Ain’t much rain falling around these parts.”

“Naw, they real close by.” Faedou waved southward. “It won’t take half a day to get there. See the Daughter?” Faedou pointed to the river that wound southwest, outflowing from Mother of Waters. “A few leagues south of here, Daughter runs into another river called the Crossings that goes straight west. Other side of the Crossings, it’s the Wildeeps. You’ll see what I mean soon enough. It don’t make no kind of sense. North of the Crossing, the land’s just like this: dried up, nothing much growing. On the south, it’s all green. Thick brush, and elephant grass. Jungle. The Road pick up there, south of the Crossings.” Faedou faced away and spat. “That’s some more ole witchcraft.”

“Captain said the Wildeeps dangerous.” Do me a favor, D., will you? Get around to all the brothers and warn them not to stray off-Road when we come to the Wildeeps. Make every brother understand his life depends on obeying. It does. In the Wildeeps there is no safety, except on the Road.

“Well, there’s beast and thing, Sorcerer. Terrible things—what God Hisself couldn’t love. Last time I went through, I swear I seen…”

“What, Faedou? What you see?”

“… I don’t know, man. Maybe I didn’t see nothing.”

“Aw, come on—what, Faedou? Don’t be like that!”

In motion the captain had the look of a cheetah. Long-legged, swift, too thin. He whirled left and right, away from cast spears, catching some as they passed. At the last man in line, he began back the other way. Ten or so of these circuits was the usual length of drills. After long weeks of Captain’s training, the brothers had the rhythm down. Everyone either threw, sprinted to retrieve his spear, sprinted back to his place in line, or else was bent over, gasping for breath.

“Something like a crocodile. But up on two legs, you know? Mouth just full of teeth! Each one as bad as a knife, Sorcerer. If that thing had bit you, it would of took out as much as my two hands could grab.” Faedou put his palms together at the wrists, curving his fingers like fangs: clamping down on his own thigh by way of demonstration.

“Mighty big bite,” Demane agreed. “Anybody else see this thing, Faedou?”

All earthly creatures shared a common scent, the tellurian signature. But (to Demane’s nose) a rare few smelled also of the stars, as if some subset of their ancestors sprang from other dust than this. There were mortal men and women in the captain’s lines of descent, yes, but the gods abounded too. That voice of his, for one; and who but a cousin descended from the Towers could manage such fast footwork? The captain was plainly too strong, as well, for a man hardly more than cord and bone. Demane reckoned that Captain cut loose this way at drills, and in battle, for brief respite from the terrible self-restraint he imposed on all his deeds, movements, and even speech at other times.

“Just me. But I ain’t crazy, Sorcerer. So don’t be looking at me like that. I seen it. In the middle of the night, I got up to pee. And seen it by the moonlight: right over in some trees. Standing close as that patch of weeds you see right there.”

“Well, how come you didn’t just wake up some—”

“I was scared, is how come. You should of seen that damn thing! Tall as the captain, Sorcerer, I swear it was. Walking around like anybody. Teeth like this!”

“All right, all right. So, what it do next?”

Captain was eating sunlight. Tasting the sun, rather, for he couldn’t absorb much through that headscarf he always wore. Darkling about the captain’s head was a heliovore’s nimbus, a sort of counterhalo—shadowy, half-starved and imperceptible to all eyes present, except Demane’s. I wish you’d take off that stupid scarf, Demane thought, not for the first time. What does it matter if they see your hair? You’d gain weight, strength, decades of life…

“Nothing. Just stood watching the camp from the forest. After a while the walking-alligator went back up into the trees. But that’s why everybody keep to the Road going through the Wildeeps. That bad stuff you hear about happen to caravans who go off-Road.”

Demane said, “I don’t see what the road got to do with it.”

“I told you. Witchcraft.” Faedou sprinkled that word around like a cook sprinkles salt: applicable to any and every dish, useful for all occasions. Perhaps in some sense it was “witchcraft” when Demane waved his hand through a cloud of mosquitoes, and then nobody else was bitten the rest of the night. But was it “witchcraft” when some unlucky brother stubbed his toe? Or bit down on sandy grit in his porridge? Everything can’t be witchcraft! “It’s them magi live down by Olorum who made the Road. Put some kind of hoodoo on it: to keep off beasts and thing. But you oughta know more about all this demon-raising business than me. Right, Sorcerer?”

Demane sighed. Back home in the green hills, they had called him Mountain Bear for his unusual size and strength. On this side of the continent, he’d picked up another name, no matter how many times he said, I ain’t nobody’s “sorcerer,” just call me Demane. He obviously tried for circumspection with the petty miracles, the intelligence gleaned from preternatural senses, the things pulled from his bag in broad daylight… Still, he’d picked up a reputation.

Drills were done. Captain dismissed the brothers, keeping back the usual two. Demane tossed brothers their oiled goatskins full of water as they came straggling back.

Messed Up threw himself down in the grass and began to guzzle. Every time the caravan had stopped at wells in the desert, Messed Up had drunk to the point of sickness. And always, in the burning stretches between wells, he’d run short and had to come begging some of yours.

“Slow down,” Demane said. “Not so much.”

Teef said, “It’s too hot for all this!” as he always did after drills. “Why the fuck Captain got us out here running around, throwing spears and shit, in the HOT ASS MOTHERFUCKEN HEAT?”

A couple other brothers—as they always did—said, “Amen. That’s right. Why?” between sips of water.

Demane snatched the upturned goatskin from Messed Up’s mouth. “How you gon’ drink the whole thing straight down? You remember how you made yourself sick all them times. Act like you got some sense for once!”

“What do it matter, Sorcerer?” Once upon a time, Messed Up’s scowl had only bespoken gormless passion. “You see they got a whole big-ass lake right there!”

“You forgot last time already? Throwing up like that? Belly hurting? You done for now.” Demane slung his arm, squeezed his hand. A silver rope of water, airborne, uncoiled above the pale dust, and then darkened a long line across it. He tossed the empty goatskin back.

These days when Messed Up scowled, whoever had thought themselves hideous could take great comfort, now recognizing themselves as beautiful. For ever since a bandit’s machète had sheared half Messed Up’s face from his skull—seventy-eight catgut stitches, to reattach cheek, lips, chin—every mug was a lovely mug by contrast with that warped leer, pulling against its sutures.

“Aw, see there?” Messed Up howled. “Damn, Sorcerer!” He tumbled over backwards, like some twenty-stone baby pounding his fists, kicking his heels, against the dirt.

T-Jawn, with no such lack of decorum, lay back on a grassy spot. “I should so like to sit out these drills as you do, M. Sorcier.” And, peering through the slatted fingers of a languid hand, he asked, “What is your secret? Do tell.” The question, the exhortation, sounded rhetorical to Demane, and he made to turn away. But, nay: earnestly meant, for T-Jawn sat up, asking, “No, truly, mon vieux: From whom did you learn such mastery of the spear?”

Demane shrugged. “My Aunty.”

Brothers fell out rolling in the grass. They joked. They laughed.

“Got my skills from Granny! Where you get yours at?”

“Was my wife learned me up. Old gal got a arm on her!”

“Where I come from, women hunt if they feel like it…” Then Demane made himself shut up. You get sick of saying the same thing over and over. Men on this side of the continent thought they were the best at everything. It was stupid! Aunty, however, needed his defense about as much as did Mt. Bittersmoke, where lightning struck in continuous cascade about a lake of brightly splashing lava. “Well, Captain don’t go easy on me, either,” Demane pointed out.

The second or third time Captain had called these drills, a near-metamorphosis had come over Demane unexpectedly. His senses sharpened, reflexes quickened, just before he’d thrown his spear. The point had caught in Captain’s robe, nearly impaled him. Since then, Demane sat out drills. He and the captain sparred spear-to-spear at the end of exercises. Nor did Captain hold back much.

“I don’t know about the rest of y’all, but it’s them two little niggas”—Barkeem nodded toward the brothers still at drills—“I feel sorry for.”

Demane, too. Every now and then, he’d ask Captain again to cut the hapless youngsters a little slack. “No,” said the captain, without variation.

Xho Xho and Walead were all sharp elbows, skinny shanks, bony knees. So were several other brothers. None of those others, however, was so cursed with bungling hands and feet. Xho and Walé were made to throw their spears twice as many times as everyone else. Ungentle hands jerking the boys into correct stance, Captain would fix their grip on the spear, tension and turn of shoulders and hips, even how far up or down they held their chins. When a spearcast failed to please him, which was most of them, the boys had to run full out—that is, stagger, hunched over with side-stitches—back and forth a time or two from where the spear lay, back to where the captain waited, hardfaced as the fatherghost these northerners called God.

“Yo, my dudes,” said a brother. “Heard they got hoes at the Station.”

The truth of this hearsay was by another brother affirmed. “Yeah. Down in some tents out past the big market.”

A latter beside the former two put forward his own intention, and inquired into other brothers’. “I’m heading down that way to see about one, damn betcha. Who else going?”

Nearly every brother was.

“’Bout you, Sorcerer?”

“I don’t do that.”

“Moi? I most certainly do,” said T-Jawn for the general edification; and then, confidingly, to Demane: “Has no one informed you then, Sorcerer? After Mother of Waters, there shan’t be any further opportunities to, ah—what was that marvelously apt phrase of yours, Barkeem?” T-Jawn popped his fingers encouragingly.

“Get your dick wet.”

“Voilà—before we come to Olorum City?”

* * *

In the green hills of home there was no such institution. And so when he’d first come from the remotest spur of the continent, to cities of the northern riviera, Demane had thought it to be a route by which men wishing to marry could meet a wife.

There, in old colonial Philipiya, skill won him the position of huntmaster for the city amir. Remunerative but silly work, bagging game for sport; and a lonely life as well, all day speaking languages other than his own, with no one to hold at night. Before a year was out, Demane had begun wondering why he’d ever traveled so far from Saxa, first love and then oldest friend, and especially from Atahly, the woman—on second thought—he really should have married. You’ll love me later as much as I love you now, and regret leaving. She was right.

Whenever he admitted to loneliness, men of Philipiya would commend to him whores. Women of exceeding beauty, was the impression he’d gotten; and not to be approached without wealth. At last, he decided he’d better marry one and settle down.

The shawl cost half his savings. The amir himself had recommended the merchant. You would need six months’ travel by ship to find another like this in the world! The silk was orange and crimson as low clouds above a sunset, stitched in thread-of-gold. Demane bought smaller treats, too, of course: pretty little bangles, candied fruit, perfume. He, the lady, and her advocates would feast together, wouldn’t they? He could discreetly leave the shawl afterwards, if the lady found him congenial. The elders might like an amphora of that grape vinegar, also from overseas and costly, so beloved by Philipiya’s rich…

The place was filthy. A long and dark hall; over doorways on the right-side wall, raggedy carpets hung. Hoarse noise and women’s sobs. The fishy reek of sex unwashed for days. Reeling and flinching, his thoughts couldn’t make sense of abomination. A carpet drew back on a girl much too young, lying atop stained sheets. No supper was laid out and there’d be no polite talk. He and his wife-to-be wouldn’t, late in the meal, stare brazenly at each other, and then cast down their eyes again, chastened by a grunt from the chaperones. Nothing he’d imagined. Motes seethed on the verminous pallet. Who fed this little girl? Not enough. “Pretty, ain’t she?” said the… merchant… proprietor? (the pimp, which word he hadn’t known then). “Youngest one I got. Silver penny if you want her.”

Gripping the rich fringe, Demane let the shawl unfurl to the floor. He shook the bright silk aloft and let it go, draping the naked child. And left. Not so long as he lived would he forget her eyes, the misuse in them, and expectation of more.

Excerpted from The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps © Kai Ashante Wilson, 2015