Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

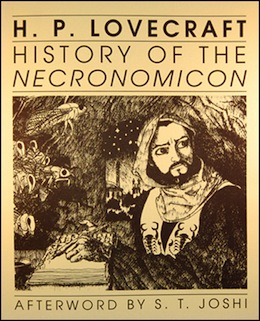

Today we’re looking at two stories: “The History of the Necronomicon,” written in 1927 and first published in 1938 by The Rebel Press, and “The Book,” probably written in 1933 and first published in Leaves in 1938.

Spoilers ahead.

“I remember when I found it—in a dimly lighted place near the black, oily river where the mists always swirl. That place was very old, and the ceiling-high shelves full of rotting volumes reached back endlessly through windowless inner rooms and alcoves. There were, besides, great formless heaps of books on the floor and in crude bins; and it was in one of these heaps that I found the thing. I never learned its title, for the early pages were missing; but it fell open toward the end and gave me a glimpse of something which sent my senses reeling.”

THE HISTORY OF THE NECRONOMICON

Lovecraft notes that the original title of the tome of tomes was Al Azif, an Arabic word for the nocturnal buzz of insects often heard as demonic howling. Its author, the mad poet Abdul Alhazred, came from Yemen but traveled extensively, stopping by the ruins of Babylon and subterranean Memphis before sojourning for ten years in the vast and haunted emptiness of the Arabian deserts. In Damascus he penned Al Azif, in which he evidently recorded the horrors and wonders he’d discovered in the ruins of a nameless desert city, where had dwelt a race older than man. Nominally a Muslim, he claimed to worship Yog-Sothoth and Cthulhu. In 738 AD he died or disappeared. Ibn Khallikan records he was devoured by an invisible monster in broad daylight before numerous witnesses.

Next Lovecraft discusses the convoluted history of the Necronomicon‘s translations and suppressions. In 950 AD Theodorus Philetus of Constantinople did the Greek translation and gave the grimoire its current title. Olaus Wormius followed with a Latin version in 1228. John Dee, the Elizabethan magician, did an English translation never printed, of which only fragments of the original manuscript survive. Victims of religious purgation, the Arabic and Greek versions are apparently extinct; Latin versions remain in Paris, London, Boston, Arkham and Buenos Aires. However, who knows what copies and bits lurk in secret libraries and mysterious bookstores? An American millionaire is rumored to have scored a Latin version, while the Pickman family of Salem may have preserved a Greek text. Public service announcement: READING THE NECRONOMICON LEADS TO TERRIBLE CONSEQUENCES, like madness and consumption by demons.

THE BOOK

Unnamed narrator exists in a state of dire confusion, shocked, it seems, by some “monstrous outgrowth of [his] cycles of unique, incredible experience.”

He’s sure of one thing—it started with the book he found in a weird shop near an oily black river where mists swirled eternal. The ancient, leering proprietor gave him the book for nothing, maybe because it was missing its early pages (and title), maybe for darker reasons. It’s not actually a printed book but a bound manuscript written in “uncials of awesome antiquity.” What drew narrator was a passage in Latin near the end of the manuscript, which he recognized as a key to gateways that lead beyond the familiar three dimensions, into realms of life and matter unknown.

On his way home from the bookshop, he seems to hear softly padded feet in pursuit.

He reads the book in his attic study. Chimes sound from distant belfries; for some reason he fears to discern among them a remote, intruding note. What he does certainly hear is a scratching at his dormer window when he mutters the primal lay that first attracted him. It’s the shadow companion earned by all passers of the gateways–and he indeed passes that night through a gateway into twisted time and vision. When he returns to our world, his vision is permanently altered, widened: He now sees the past and future, unknown shapes, in every mundane scene. Oh, and dogs don’t like him, now that he has that companion shadow. Inconvenient

He continues to read occult tomes and pass through gateways. One night he chants within five concentric rings of fire and is swept into gray gulfs, over the pinnacles of unknown mountains, to a green-litten plain and a city of twisted towers. The sight of a great square stone building freaks him out, and he struggles back to our world. From then on, he claims, he’s more cautious with his incantations, because he doesn’t want to be cut off from his body and drift off into abysses of no return.

What’s Cyclopean: The Book is found amid Scary Old Houses. Fungous, even.

The Degenerate Dutch: Describing Alhazred as “only an indifferent Moslem” (sic) is a bit rich.

Mythos Making: Here, as advertised, we get the history of Lovecraft’s most infamous volume, its equally infamous author, and its various ill-fated editions. We also get a call-back to Chambers’ The King in Yellow, formally pulling it into the Mythos—as fiction inspired by mere rumors of the Al Azif.

Libronomicon: Reading the Necronomicon, we hear, leads to terrible consequences—but we meet many people throughout Lovecraft’s oeuvre who’ve done so with little more than a shudder. The unnamed book in The Book, on the other hand…

Madness Takes Its Toll: Maybe you don’t want to know the secrets of the cosmos after all.

Anne’s Commentary

“The Book” reads like an abandoned fragment. For me it’s full of echoes. The overall idea of travel through gateways, into other dimensions of time and space, life and matter, is reminiscent of the Randolph Carter/Silver Key stories. The last bit of extramundane travel brings to mind the Dreamlands with its pinnacles and plains and towers and great square buildings that inspire terror—maybe because of some masked priest lurking within? But the strongest echoes issue from “The Music of Erich Zann.”

We’re never told exactly where the narrator lives. At first I thought London, or Kingsport. Doesn’t really matter—whatever the city, it seems to boast a sister neighborhood to the Rue d’Auseil. It has a rather unpleasant sounding river, oily, mist-ridden. The waterfront’s a maze of narrow, winding streets, lined with ancient and tottering houses. The narrator’s house looks out from high upon all the other roofs of the city, and he’s doing something that attracts a shadow, and he listens for spectral music to sound among the chimes from everyday belfries. The shadow comes to his high window, and scratches, and accompanies him away on a mind-spirit trip to the outside—such a journey as Zann takes, while his body automatically fiddles on?

Anyway. “The Book” is a case-study in why one should not read mouldy tomes of uncertain origin. In fact, it’s better to stay right out of bookshops that carry such tomes. Is the “Book” in question actually our next subject, tome of tomes, the Necronomicon? It doesn’t have to be, but maybe, say a copy of the Wormius translation scratched down in the dead of night by an errant monk, constantly looking over his shoulder for Pope Gregory’s tome-burning goons.

But the Necronomicon, now. And Lovecraft’s “History” thereof. It’s a nice bit of canon-organization, stuffed with specifics both factual and invented. The Ommiade (or Umayyad) caliphs were real, as was Ibn Khallikan, author of the biographical dictionary Deaths of Eminent Men and of the Sons of the Epoch, compiled between 1256 and 1274. Real, too, were patriarch Michael and Pope Gregory and John Dee. Theodorus Philetas was made up, as was the Olaus Wormius accused of the Latin translation of 1228. There was, however, a Danish scholar of the same name, who lived from 1527 to 1624. The Arabian deserts mentioned, Rub-al-Khali and ad-Dahna, are real, and Irem City of Pillars is at least the stuff of real legends, including one in which a King Shaddad smites a city into the sands of the Empty Quarter, where its ruins lie buried–at least until Abdul Alhazred explores them, to be followed by the narrator of “The Nameless City.”

Lovecraft may be laying down the law about some aspects of his great literary invention, but he leaves plenty of wiggle room for his friends and all Mythos writers to follow. Yeah, it seems that various religious groups destroyed all copies of the Arabic and Greek versions of the Necronomicon. Yeah, there are only five “official” Latin copies left to scholardom. But wait, “numerous other copies probably exist in secret.” Yes! Just two possible examples, that American millionaire bibliophile with the 15th-century Latin version—maybe it was Henry Clay Folger, and maybe he wasn’t just interested in Shakespeare folios. Maybe there’s a super-top-secret basement annex to the Folger Library dedicated to the Necronomicon and other occult delicacies! I say we delegate Ruthanna to check this out.

Then there’s R.U. Pickman, whose ancient Salem family may have sheltered a Greek version. R.U. is Richard Upton to us, the infamous painter with ghoulish tendencies. I doubt he would have taken a priceless tome into the Dreamlands underworld—too humid and dirty. So if we can only find that North End studio of his in Boston!

If Ruthanna takes the Folger, I’ll take the North End.

But anyway. It’s interesting that Lovecraft concludes with the speculation that R. W. Chambers was inspired by the Necronomicon to invent his madness-inducing play, The King in Yellow. When actually it could be the other way around. The King was published in 1895, and Lovecraft read it in 1927, the same year he penned his “History.” Have to note that the Necronomicon itself first appeared in 1924 (“The Hound“), Abdul Alhazred in 1922 (“The Nameless City.) It’s a cute detail, at any rate, making our fictional grimoire all the more real in that it could have influenced Chambers as well as wizards through the ages.

And Abdul Alhazred! He has an incredible backstory, doesn’t he? It deserves more than a note by Ibn Khallikan. Mythos cognoscenti! Has anyone ever written a full-scale biography in novel form of our mad poet? If not, or even if so, I’m putting it on my list of books to write, after much research into those caves and subterrane labyrinths that lie beneath the limestone of the Summan Plateau in ad-Dahna. I’m sure an inveterate insane traveler like Alhazred could have found a link through them into the secrets of pre-human civilizations, probably reptilian.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Books, man. They carry knowledge unpredictable from the cover. They leave ideas and images seared in your mind, impossible to forget, reshaping your reality in spite of your best efforts, and yet you crawl back for more. Here you are reading this, after all. (What is the internet if not the world’s largest book, endlessly unpredictable and full of horror in unexpected corners?)

That conflict, between knowledge’s irresistible lure and its terrible consequences, is at the heart of Lovecraft’s most memorable creations. And who here hasn’t picked up a book knowing it would give them nightmares?

Our narrator in “The Book” certainly has that problem. At the end, he promises to be much more cautious in his explorations, since he doesn’t want to be cut off from his body in unknown abysses… which is exactly the situation from which he narrates. It’s an effectively disturbing implication.

“Book” suffers primarily from its place in Lovecraft’s writing timeline—it’s his third-to-last solo story, and the last that can merely be described as pretty decent horror. Immediately afterwards, “Shadow Out of Time” and “Haunter of the Dark” will take vast cosmic vistas and terrifying out of body experiences to a whole new level, this story’s shivers expanded and supported by intricately detailed worldbuilding. No blank-slate white room opening is necessary to make Peaslee’s experiences unfathomable, and his amnesia draws away like a curtain.

It’s not merely that “Book” tries out themes later expanded to their full flower. Not long before, “Whisperer in Darkness,” “At the Mountains of Madness,” and “Dreams in the Witch House” also build out these ideas to fuller potential. In “Whisperer” in particular, much is gained by having the sources of tempting, terrifying knowledge be themselves living and potentially malevolent. So this story seems more a resting place, a holding pattern playing lightly with the themes that obsessed the author throughout the early 30s.

“History of the Necronomicon,” meanwhile, is not really a story at all. It’s a couple of pages of narrativized notes, the sort that I imagine most authors produce around any given project. (It’s not just me, right?) It’s still fun to read, and I rather wish we had more of these—for starters, the bits of alien culture that don’t make it into the final drafts of “Whisperer” and “Shadow Out of Time” and “Mountains.”

Some of “History” does appear elsewhere. I know I’ve seen that line about Alhazred being an indifferent Muslim before; it makes me roll my eyes every time. But there are also the details about the Necronomicon’s different editions (and very, very limited non-editions), along with an answer to last week’s question about rarity. Five copies are known to exist, representing two of the book’s four editions. Others are supposed to exist in private collections: in our readings so far we’ve encountered—among others—last week’s original Arabic, a disguised copy belonging to Joseph Curwen, and the one held by worms on the dreamward side of Kingsport. “A certain Salem man” once owned a copy of the Greek edition. Plenty of people throughout Lovecraft seem to have witchy Salem ancestors, but I can’t help suspecting that must have been another belonging to either Curwen or one of his associates.

Lots of people still seem to have read the thing, suggesting that rumors of terrible effects don’t often prevent those five libraries from loaning it out. No surprise—the urge to share is probably almost as strong as the urge to read.

Next week, Lovecraft teams up with Duane W. Rimel, and probably also Shub-Niggurath, to explore the unlikely geography of “The Tree on the Hill.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s non-Hugo-nominated neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land and “The Deepest Rift.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. The second in the Redemption’s Heir series, Fathomless, will be published in October 2015. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

“The History of the Necronomicon” is a minor essay which exists to detail points of continuity while “The Book” is an enigmatic fragment of the abandoned prose version of “Fungi from Yuggoth”.

Weird Tales: “The History of the Necronomicon” was published as a chapbook in 1938 but until recently was rarely reprinted. “The Book” appeared in Leaves #2 in 1938.

New Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos: includes “The Black Tome of Alsophocus”, an expansion of “The Book” by someone named Martin S. Warnes. I presently remember little of it, save that Nyarlathotep was involved.

Animation of Madness: see here.

Anyway: did anyone make it to NecronomiCon Providence?

Even in the never intended for print history of the Necronomicon, Lovecraft did a fine job of mixing the real and the imaginary to give the thing a strong sense of verisimilitude. He gets a few things wrong. Al-azif apparently means the whistling of the wind or a weird noise. And of course, Wormius (né Ole Worm) lived much later, but who could resist a name like that? He just didn’t fit properly in a chronological sense. But why has no one ever tried to connect him to De Vermis Mysteriis? Or is that a bit too on the nose?

But just about everybody else was real. Ibn Khallikan was a real Arab biographer, John Dee is well known (his connection was apparently Frank Belknap Long’s idea). Both Gregory IX and Michael I were quite real. It’s just all so plausible.

I don’t know if there’s been a novel length bio of Al Hazred. Derleth altered his fate in “The Keeper of the Key” and had him dragged off to the nameless city to meet a terrible end rather than being torn apart by invisible demons in Damascus. Typical really. I’ll allow the “indifferent Muslim” description. We’re talking about a man who died roughly a century after Muhammad in a time and place where Islam was pretty vigorous and vigorously enforced. Obviously he had to put up a front. Joseph Curwen could just as easily have been described as an indifferent Christian while he was busy pretending to fit into the mainstream in order to get a wife. Still, there’s probably a place for such a biographical novel, though the author would have to deal with all the issues surrounding the name and pick one of the many explanations.

As Schuyler notes, “The Book” was an attempt at a prose version of “The Fungi from Yuggoth” and it’s themes may be better discussed when we cover that poem cycle. It’s certainly an interesting start, though.

ETA: A quick look at Wikipedia and apparently there is a novel biography. Alhazred (2006) by Donald Tyson. He also wrote a Necronomicon. No idea if it’s any good.

I know there have been at least a few published faux-Necronomicons — I had the cheesy 80s paperback edition that was probably found in the “occult” section of my local Waldenbooks

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/58973.The_Necronomicon?from_search=true&search_version=service

And I’ve also heard of someone who created a version by cutting & pasting random passages in Arabic so it would look suitably exotic to a non-Arabic speaker.

And didn’t Lin Carter have an elaborate plan to try to gin up the entire thing by taking such fragments as appeared in Lovecraft’s fiction and trying to “fill in the blanks”? Which I think would be challenging given that the type of material in Alhazred’s tome seems to vary depending on the narrative needs of the story at hand …

Sorry if this sounds ignorant, but why is referring to Alhazred as an “indifferent Muslim” so offensive? Given the culture he lived in, he probably found it expedient to go through the motions of paying lip service to Islam, at least in public. But I can’t imagine he ever put much stock in the Qurʾan, what with all the talk of blasphemous cosmic secrets and pre-human demon-gods in the Al Azif.

It’s kind of like describing Marranos as indifferent Christians–a description that would please neither Jews nor Christians. Passing (or failing to pass) isn’t the same thing as not being very good at something.

Alternatively, it’s possible that Alhazred did in fact believe that there was one god named Allah who dances on mountain tops under the protection of Nyarlathotep–in which case he would be not so much indifferent as heretical.

Mind you, I’m extrapolating based on my understanding of belief-focused religions. Judaism is a tribal identity as well as a religion, and that identity isn’t lost when beliefs change. So it would be perfectly possible to be an indifferent Jew who primarily worshipped Shub-Niggurath. It would get you a very stern conversation with your rabbi, though.

It’s also been pointed out that “Abdul Alhazred” is bad Arabic, and the true name was likely something like “Abd al-Azrad”.

Try to find Joan Stanley’s “Ex Libris Miskatoni – A Catalogue of Selected Items from the Collections of the Miskatonic University Library” (Necronomicon Press, 1993) which has a detailed history of the Necronomicon, its editions, translators, etc. It turns out that the book is actually not that rare, which probably doesn’t surprise anyone here familiar with how many copies seem to show up in the hands of unfortunates …

You could always claim you were extrapolating from that “be fruitful and multiply” verse…

I read both the Tyson books. He eschewed nameless horrors for some rather gross stuff, as I recall. Okay for passing the time.

If “Al Azif” actual means eolian noises, that’s intriguing. Parts of my building, and sometimes right here in this apt., get rather tuneful when the wind is right.

“Try to find Joan Stanley’s “Ex Libris Miskatoni – A Catalogue of Selected Items from the Collections of the Miskatonic University Library” (Necronomicon Press, 1993) “

Actually … “Ex Libris Miskatonici” …. isbn 0940884569 . And best to try Inter-LIbrary Loan, what folks are asking online for it is scary, unreal, almost blasphemous ….. especially for, I think, 60 pages or so.

That said, it’s a delightful book.

I went to NecronomiCon. It was an absolute pleasure from start to finish with art exhibits, film screenings, live radio plays and podcasts, walking tours of Providence, scholarly presentations, an Eldritch Ball and numerous authors presenting their work. Seriously, if you even have passing interest in Lovecraft it is well worth going at the next one in 2017. Check out the images posted to all the HPL related Facebook groups.

The Book was pretty much abandoned when HPL decided to do Fungi from Yuggoth as a sonnet cycle.

I. The Book

The place was dark and dusty and half-lost

In tangles of old alleys near the quays,

Reeking of strange things brought in from the seas,

And with queer curls of fog that west winds tossed.

Small lozenge panes, obscured by smoke and frost,

Just shewed the books, in piles like twisted trees,

Rotting from floor to roof—congeries

Of crumbling elder lore at little cost.

I entered, charmed, and from a cobwebbed heap

Took up the nearest tome and thumbed it through,

Trembling at curious words that seemed to keep

Some secret, monstrous if one only knew.

Then, looking for some seller old in craft,

I could find nothing but a voice that laughed.

Anyway, one of the very most delightful anthologies in the last few years is from PS Publishing and is called The Starry Wisdom Library edited by Nate Pedersen. It is only available as a HC from their website but it is well worth the money. It purports to be an auction catalogue from 1877 of the contents of the Starry Wisdom library which was to be sold off. No one knows why the auction never actually took place. This offers a physical description of most of the tomes in the Eldritch Library, and then offers a history of their provenance, each book taken on by a different author.

From the opening of “The Book”:

My memories are very confused. There is even much doubt as to where they begin; for at times I feel appalling vistas of years stretching behind me, while at other times it seems as if the present moment were an isolated point in a grey, formless infinity.

Sounds as much like John Carter as it does like Randolph Carter… must be a genetic predisposition in the Carter family.

On the history of the “Necronomicon”, I am certain that Borges would have read the copy in the Biblioteca Nacional in Buenos Aires from cover-to-cover (must have been before he was director, because he lost his eyesight at about that time), his resultant madness inspired “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”. Borges later wrote a mythos tale.

@5 R Emrys,

“Indifferent Moslem” sounds apt to me; HPL (a confirmed atheist) probably pictures Alhazred as being akin to the deists of his beloved 18th century. Hence, although he has no belief in the Abrahamic god, he’s perfectly willing to pay lip service and play along. Less trouble that way

But deists didn’t worship…

*looks at art on dollar bill*

Never mind.

@@@@@R.Emrys

Ah, okay. I follow you now

Just for the record, I am NOT an indifferent acolyte of Nyarlathotep. Just so he/she/it knows.

I haven’t read the The History yet, but could “indifferent Muslim” refer to how he was before he became a worshiper of Elder Gods?

From the sample, the Tyson Necronomicon looks better than the Simon Necronomicon but it’s yet another paperback. There should at least be a leather-bound version…

@16: No.

“He was only an indifferent Moslem, worshipping unknown entities whom he called Yog-Sothoth and Cthulhu.”

Ellyne @@@@@ 16: It says he’s an indifferent Muslim *because* he worships Elder Gods. Lovecraft isn’t actually particularly judgy about this. It’s just that the phrasing causes my eyebrows to rise so high they float off my forehead, every time I encounter it.

MTCarpenter @@@@@ 10: Somehow I’d never realized Fungi From Yuggoth was a sonnet cycle. We’re not getting into all the poems, but I think we’ll have to add that one to the list.

@18

Yeah, the poetry is generally better ignored, but Fungi is worth a look.

@19: Apparently, replacing random letters in words with apostrophes isn’t a sure-fire way of producing True Art. Who knew?

Concerning Eldritch Tomes: the variorum Lovecraft is out! Actually, it has been for a while, I just don’t read S. T. Joshi’s blog very often.

@18 Fungi from Yuggoth is 100% worth to be in the list. It is exquisite. I also highly recommend Pugmire’s Some Unknown Gulf of Night that is inspired by Lovecraft’s sonnet cycle – you can find excellent audio version of this book on YouTube. All Pugmire’s work is pure eldritch beauty and very recommended for all Lovecraft’s fans.

@20 The main problem with HPL’s poetry was his blind devotion to the 18th century style. As a result, most of his poems are so dead they can eat your brain. Yet I share Joshi’s opinion that Lovecraft’s weird and humorous poetry isn’t half bad, especially in comparison with most of his poetic output. He may have thought himself no more than a technically skilled poetaster, yet he did have his flare-ups of genius like Nemesis or drinking song from The Tomb, that are among my favourite poems ever.

Re Fungi, a must reread! I find the section on Nyarlathotep particularly haunting, a sort of Mythos “Second Coming.”

Aiee! And what rough beast, its hour come round at last

Slouches towards Arkham to be born?

So, did anyone read the “indifferent moslem” as *flamboyant gay voice* “Abdul Alhazred don’t care! Abdul Alhazred don’t give a shit!”…?

*crickets*

Just me then…?

Tyson’s Alhazred was okay. I think he was trying for an Umayyad-era Vathek, a delve into forbidden-knowledge and evil.

As for Lovecraft’s “indifferent Moslem”: he was sketching a character and a setting in as few words as possible, and salting it with irony. In this case we have an Arab (or at least an Arabian) who is expected to be Muslim, and is playing the part; but everyone in Damascus knows he doesn’t mean it. They also whisper that he is worshipping other gods on the sly, but they cannot prove it.

I think we’re all on such a hair trigger for “racism” and, now, “Islamophobia” that this innocuous comment raises hackles. Well, it shouldn’t.

Not so much hackles as eyebrows, really.

As a Carter myself, I can confirm this.

The opening plot-point of ‘The Book’ — the purchase of an arcane tome (for free) in an obscure, sinister bookstore from a sinister old man — has a remarkably similar theme to another fragmented Lovecraft work, ‘The Descendant’, which I only discovered last night.

In it, a young, enthusiastic dreamer and would-be student of the occult named Williams purchases (not for free, but for a very small price) a copy of the Necronomicon from a sinister bookstore in Clare Market, London, owned by a sinister Jew. Williams happens to be staying at the same inn as the alleged protagonist of ‘The Nameless City’, the sanity-shattered Lord Northam.

Northam, a former scholar and aesthete, who has pursued every kind of mystical, religious and occult tradition to its uttermost degree, is now a broken man, drowning out the pain, not in booze, but in novels “…of the tamest and most puerile kind…” and has a terrible aversion to the sound of church bells, which sends him into fits of screaming. When he discovers Williams has brought home the dreaded Necronomicon, he is, quite naturally, alarmed. Presumably terrible things would have followed, but Lovecraft apparently didn’t finish the work, so that’s where it ends.

It’s possible that the narrator of ‘The Book’ is actually Williams from ‘The Descendant’. Clare Market is less than a ten minute walk from the river Thames, which could be that very “…black, oily river where the mists always swirl…”.

Compare these lines about the bookstore owner:

There’s no mention of a set of footsteps following Williams, however, and, at least at that point in time, rather than living in a house with family and servants, he is staying at an inn, where he shows his purchase to Northam. Then again, the narrator of ‘The Book’ admits his memories are muddled and confused, so who knows?

@1:

There isn’t much to remember about the Back Tome of Alsophocus. The plot can largely be summed up as “My tome’s more blasphemous than yours, so myeuh!”

A few of the above comments mention Donald Tyson’s *Alhazred: Author of the Necronomicon*, but I didn’t see anyone note that this is actually an answer to Anne’s question “Has anyone ever written a full-scale biography in novel form of our mad poet?” So I’m just putting that on the record…