Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

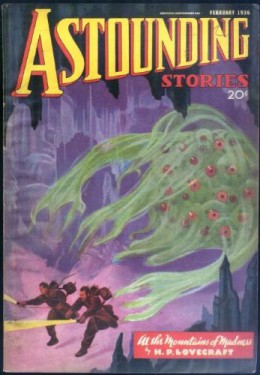

Today we’re celebrating Halloween with “At the Mountains of Madness,” written in February-March 1931 and first published in the February, March, and April 1936 issues of Astounding. For this installment, we’ll cover Chapters 1-4 (roughly the equivalent of the March issue—we still have a squamous cookie for anyone who can confirm the original division). You can read it here.

Spoilers ahead.

“Existing biology would have to be wholly revised, for this thing was no product of any cell-growth science knows about. There had been scarcely any mineral replacement, and despite an age of perhaps forty million years the internal organs were wholly intact. The leathery, undeteriorative, and almost indestructible quality was an inherent attribute of the thing’s form of organisation; and pertained to some palaeogean cycle of invertebrate evolution utterly beyond our powers of speculation.”

Summary: William Dyer, professor of geology, led the 1930 Miskatonic University expedition to Antarctica. Since then, he’s refused to tell all that happened in that cryptic land of ice and death; in fact, he’s discouraged others from Antarctic exploration. But now the Starkweather-Moore Expedition is poised to invade the frozen continent, and he must speak, for the sake of humanity itself.

The MU expedition means to field-test a revolutionary light-weight drill designed by engineering professor Frank Pabodie. With the drill’s ability to quickly pierce strata of varying hardness, the scientists hope to extract fossil specimens never before obtainable. The discovery of primordial organisms—seaweeds, crinoids, trilobites—soon justify their hopes. Biologist Lake also pieces together a foot-wide fossil he speculates to be the triangular footprint of an amazingly advanced organism. Dyer thinks the “footprint” is just a ripple-effect in metamorphic rock, but when Lake unearths more triangular prints to the west of their camp, Dyer allows him to lead a large prospecting party into unexplored territory. Dyer, Pabodie and several others remain behind, growing envious when Lake reports finding a range of mountains higher than Everest! What’s more, the peaks have curiously regular formations, like clinging cubes, ramparts, perfectly square or semi-circular cave mouths.

Lake’s party camps in the foothills of the prodigious mountains. Their borings with Pabodie’s drill break into a cave system where they find a treasure trove of plant and animal fossils. Thrilling enough, but they also find miraculously well-preserved specimens of the creature which made the triangular footprints! They appear to be huge radiates with barrel-shaped bodies six feet high. A starfish-shaped, ciliated “head” dominates one end, with protruding tubes that contain eyes and mouths. On the other end are five muscular limbs ending in triangular paddles or feet. The five divisions of the barrel-body sport tentacles that branch into smaller and nimbler appendages, while the folds between divisions hide seven-foot membranous wings. Lake remarks that the organisms bring to mind the “Elder Things” of the Necronomicon, which supposedly created all earth life by mistake or in jest.

Dyer’s party prepares to join Lake’s, all the time listening to wired reports of further developments beneath the tremendous mountains. Lake secures fourteen giant specimens, but must corral the sledge dogs on the far side of the camp, for the dogs hate the things. He dissects one radiate, which leads him to surmise that it was amphibious, animal but reproducing through spores, and probably had more than five senses. Also its five-lobed brain and nervous system are incredibly complex. That it could have evolved in time to leave prints in Archaean rock confounds the biologist, who again recalls legends of alien races that filtered down from the stars in Earth’s youth.

Overnight, a horrific windstorm stampedes out of the west. Buffeted even at their camp, Dyer and company fear for Lake’s party. Their fear intensifies when radio communications go silent, and they take the expedition’s last plane to find out what’s happened.

To their horror, they find nothing but destruction and death at Lake’s camp. Also mystery, for though the storm has flattened tents and snow shelters, battered planes and drilling gear, even mangled the corpses of men and dogs, wind could not have left one scientist and one dog roughly dissected. It could not have neatly excised meaty chunks from other corpses. It could not have handled equipment and books and supplies with intelligent curiosity, though no conception of what the things were used for. One sledge is missing. So is one man, Gedney, and one dog. So are all fourteen radiate specimens. Well, no, not quite all. Six damaged specimens have been buried in a snow mound eerily like the star-shaped green soapstones Lake also discovered in the fossil-cave. Right down to the markings of grouped dots which look eerily like some kind of writing.

Dyer and company can only conclude that Lake’s party went mad from the intensity of the storm. Or at least Gedney went mad. Now, having wreaked havoc in camp, he’s taken the missing sledge and dog up into the mountains. Despite their height, there are passes a skilled climber could negotiate.

Dyer and Danforth, a brilliant graduate student, take flight in a lightened plane, meaning to cross over the mountain range. They want to find Gedney, if possible. They also want a look at lands never before seen. As they rise, the formations at the peaks grow disturbing in their regularity, as does the bizarre whistling or piping the wind makes in the numerous caves. These mountains of madness make Dyer think of primal Leng, and he wishes he hadn’t experienced a mirage on the way to Lake’s ill-fated camp, one in which ice-vapors seething over the peaks seemed to mirror a Cyclopean city beyond.

The plane tops the range at last, and Dyer and Danforth get their first glimpse of an elder and alien world! However, we readers must wait until the next installment to glimpse what they glimpse, gaspingly.

What’s Cyclopean: The city in the expedition’s “mirage,” and the city outskirts in the mountains (Elder Thing ‘burbs?) that Dyer still insists are natural formations like the Giant’s Causeway. Don’t you know, man, that once you say “cyclopean,” it’s too late to deny you’re looking at architecture.

The Degenerate Dutch: Only white guys on this expedition, allowing everyone to focus all their xenophobia on the terrifying prospect of non-human intelligence.

Mythos Making: This story gives us some important new bits of Earth’s very long timeline, but also connects with previous and upcoming stories—the Antarctic plains are reminiscent of (or possibly just are) the plateau of Leng, there’s overlap between this Miskatonic-sponsored expedition and the ill-fated one to the Yithian Archives in Australia, and Dyer mentions in passing the legends of the Mi-Go from “Whisperer in Darkness” and Wilmarth’s study of Cthulhu cults.

Libronomicon: Is there anyone in Massachusetts who hasn’t read the Necronomicon? Is it part of Freshman Orientation, or just a Rush Week challenge set by the Omega Omega Omega frat?

Madness Takes Its Toll: Whatever Danforth saw, that he won’t talk about, is behind his nervous breakdown. Where are Peaslee’s psychologists in all this?

Ruthanna’s Commentary

As I write this, astronomers are arguing seriously about whether a particular star, 1500 light years away, shows signs of a Dyson Sphere under construction, and thus of an alien civilization. If they’re there, if they’re real, they are people like us—people who share our inability to stay content in a single ecological niche, who break down and reform their environments to suit their own needs, people who adapt their world to the point of destruction. Such people would be fascinating to know, and very, very dangerous. But perhaps it’s only cometary debris behaving in unprecedented and inexplicable ways, out there in the dark. Some people would find that a relief.

In the first four chapters of “Mountains,” Dyer too hovers on this cusp, caught between the rational assumption that anything not made by man must have natural causes, and the wonder and terror of admitting you aren’t alone—and that the other guy may have outpaced you a long time ago.

This being Lovecraft, of course, everyone is existentially horrified by the prospect.

Modern science has overthrown the specifics of the Miskatonic Expedition’s findings—the Mountains surely ought to show up on satellite, unless they’re jutting from the Dreamlands like that cliff in Kingsport—but for the most part it’s just made the explorers’ excitement over their initial discoveries feel a bit understated. Still-organic tissue millions or billions of years old? We just got the disappointing news that DNA from the Jurassic must all be thoroughly decayed; a mummified mammoth is probably the best we can hope for. Modern paleontologists would want to fly one of these incredible samples back to civilization for sophisticated testing post-haste—and wouldn’t that have made an even more troubling story? (More like “Out of the Aeons,” perhaps.)

I do wonder if some of this stuff has spent intervening time in the Dreamlands. It would explain both the lack of decay and that intriguing “mirage”—you know, the one that everyone sees the same way.

This is one of Lovecraft’s longer stories, and I’m kind of ambivalent about that length. It drags a bit, especially at the beginning, in spite of the awe-inspiring descriptions of landscape and the tantalizing (or frustrating) hints of what’s to come. The characters’ denial of what they’re seeing wears thin, one starts to get the point about the raw and terrible beauty of Antarctica, and one wants to get to the good stuff.

At the same time, the style is appropriate and evocative—this is written with the kind of detail and narrative (admittedly with added existential flailing) found in really old journal articles, the kind that are as much travelogue as scientific report. It has the strengths and weaknesses of Tolkien-style quest descriptions, leaving the reader feeling like she’s been through the long journey beside the characters, for good and ill. (Maybe that smoking mountain at the beginning is in Mordor? Is Mordor anywhere near Leng?)

The hints of what’s to come, toward the end of Chapter IV, are intriguing. Not just the reality of the Elder Things, but the eventual empathy. There’s a whole epic happening in the background, of people awakening after aeons of hibernation, trying desperately to understand the strange creatures and objects around them. And burying their dead, with headstones, before seeking more familiar ground.

Still, as Dyer and poor Danforth crest the mountains, I’m just as happy to finally join them in the revelations on the other side.

Anne’s Commentary

Before I read “At the Mountains of Madness” for the first time, I’d already rooted a tattered paperback out of a library sale box. It was by some guy named Alfred Lansing, and it was called Endurance. The subtitle was “Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage.” I didn’t know who Shackleton was, but I liked incredible things. Also voyages, as in “Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea,” where Kowalski was always being bowled over by marine monsters busting through airlocks. The book turned out to be about Antarctica, and how Ernest Shackleton and crew got caught in the ice—well, their ship did—and had to eat the dogs, if I remember rightly, and ran from leopard seals, and finally made it to this barren Elephant Island, and then Ernie STILL had to navigate a million stormy miles in a tiny boat to rescue EVERY SINGLE ONE OF HIS MEN. Including the stowaway. Wow. I’ve been in love with Antarctica ever since.

Plus penguins, right? [RE: “Grotesque” penguins, according to the text. Either he’d never seen one, or BIRDS + OCEAN = SCARY.]

That being the case, “Mountains” had me at line two, when it talked about the “contemplated invasion of the Antarctic.” By paragraph four, it had also packed in enough specifics to convince me the MU Expedition was the real thing, and had mentioned my old friend Shackleton. This story couldn’t go wrong, I thought, and it didn’t.

It has never gone wrong for me. Of all Lovecraft’s fictions, this is the one I want to live in, so long as I can be Dyer or Danforth. Probably Dyer, because he doesn’t go nuts due to sight of an ultimate horror. Just having a whole summer in Antarctica would be amazing. Having Pabodie’s drill to root out fossils, doubly amazing. Breaking into a cave system housing not only the fossils of known orders and phyla but the utterly unclassifiable? Triple and quadruple amazing. But to fly over the peaks of the highest mountains on Earth? First of all, I could read the line “Everest out of the running” a thousand times, and it would still thrill me. As for what lies beyond the mountains?

I’m sorry, Ruthanna. I know it’s blasphemy, but if I have to pick, I’m passing on the Yithian Archives in order to roam the aeons-deserted corridors of the Elder Ones’ city, the heart of an alien civilization preserved in eternal ice. Well, eternal in human terms. I guess it may eventually thaw out, say, in the time of the Coleopterans.

But the city must wait. Technically Dyer and Danforth haven’t seen it yet. Yeah, poor guys, all they’ve had to keep them going are the wonders of the boreal realms, with an added spice of mirages, science-shaking discoveries, and gory conundrums.

This reread, I’ve been struck not by the sheer density of detail—that’s got to hit the most casual of readers, even if they skim over the technical stuff instead of savoring it. No, it’s the aptness of that detail to the narrator, Dyer, and to his upfront-stated mission. He’s a geologist and professor, so unlikely to be vague in any earnest communication. He’s trying to establish himself as a careful observer and reliable historian. If people are going to harken to his warnings, they have to trust him, and his unshaken sanity. Put him into a Congressional hearing! Bring on your interrogators and skeptics! He can handle them, if anyone can.

At the same time, it’s nice strategy to make him acquainted with Mythos lore before his abrupt immersion into its reality. He’s looked into the Necronomicon and talked to that notorious MU folklorist Wilmarth. He’s seen Roerich’s paintings of hill ruins, and Clark Ashton Smith’s uncanny pictures, too. He knows about the Pnakotic Manuscript, and Tsathoggua, and Leng. His companion Danforth also knows about the Mythos, because he’s a great reader of weird literature, able to quote Poe at the sight of smoking Mt. Erebus.

Actually, Pabodie and Lake also know something about the Mythos. I guess if you’re a professor at MU, you kind of absorb it through your pores.

Another nice bit of character building—Gedney, the grad student who’s supposedly crossed the mountains of madness on foot? Of course he could do it—he’s one of the party that made the arduous ascent of Mt. Nansen earlier in the expedition.

My second new observation is how Lovecraft subtly relates this, arguably his most rigorous science fiction tale, to the fantasy of the Dreamlands. Could it be that mythic Leng was not in Central Asia but on the Antarctic superplateau beyond the mountains of madness? After all, the horizon-grazing midnight sun throws a dream-like red glow over the stark landscape, and the roiled atmosphere supplies mirage after mirage, at least one of which may turn out to be a premonitory vision.

I do know this. Randolph Carter can have the sunset city for the place of his heart’s desire, as long as I can have the frozen metropolis of the Elder Things.

Cold never bothered me anyway.

Join us next week, on the other side of the Mountains, for Chapters 5-8.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in Spring 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the sequel Fathomless out today. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

At the Mountains of Madness is still one of Lovecraft’s greatest stories, even if it was something of a career-killer.

Astounding Stories: Part 1 was the cover story for February 1936. Frank Belknap Long also has a story in this issue: “Cones”.

Geology the H. P. Lovecraft way!: in Scientific American.

Master of the Mountains of Madness!: Nicholas Roerich.

Arthur C. Clarke: unsubtly parodied this story in 1940 as “At the Mountains of Murkiness”. It was omitted from his Collected Stories but S. T. Joshi later reprinted it as the opener to The Madness of Cthulhu: Volume 1.

Shoutout for Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea and Kowalski! <3

Is there fanfic out there of the crew of the Seaview running into Lovecraftian horrors? Now I totally want to read that.

Still one of my favorite stories. And why do I have to choose between the Yithian archives or the Elder Things’ city?

Although the whole “Ha! Ha!, these weird bodies we’ve found look exactly like the ones mentioned in that Blasphemous Tome; isn’t that a funny coincidence?” card does get played a few times too often in Lovecraft’s later stories.

Also possibly of interest:

http://store.cthulhulives.org/collections/dark-adventure-radio-theatre/products/at-the-mountains-of-madness-dark-adventure-radio-theatre-cd

This is almost certainly my favorite Lovecraft tale. It’s true that some of the bits in this section bogged down a little, especially the info dump, but the length still feels right.

Everybody does seem too familiar with the Necronomicon and the mythos in general. Dyer probably has the best reason to have some familiarity with it all, thanks to his participation in the Peaslee expedition. Lake could have been on that expedition, too, I suppose, which could have led him to dig into this stuff and develop his unorthodox theories. The narrator also comes back to whatever it was that Danforth saw a little too often. It’s rather unsubtle foreshadowing, though it does feel in character.

I wonder if this story, and especially chapter 3, had any influence on John Campbell’s “Who Goes There?” There are clearly some similarities. Antarctic expedition finds something strange, it thaws out alive and then wreaks havoc.

The explorers may react to alien life with horror, but the story is sympathetic to them. By the end, it’s perfectly clear the ancients they dug up had no more reason to think the humans were an intelligent species than the humans did them. Their dissection of humans was probably, to them, no more shocking than the humans’ dissection of one the “aliens” was to the humans–and just as shocking to the guys who woke up and saw what some unknown entity (it can’t be those dumb apes or the dogs) had done to Pauline.

This story always gets me for the way the monsters are the ones experiencing the real horror story. They wake up to find one of their own hideously butchered. Others are dead. They’re day is only going to go downhill from there.

Though the presentation here is being split into three parts, my comments below are intended to apply to the story as a whole.

As a connoisseur of Lovecraft’s use of subterranean settings, I find much of interest in At the Mountains of Madness. In his early stories, most of his fictional caves were just generic cavities, with little geological plausibility. Though one of his first stories (“The Beast in the Cave, written in 1905) was set in the famous Mammoth Cave, he had not seen a real cave himself until he visited, in June 1928, the Bear’s Den near Athol, Mass.,where there are several little granite grottos. Then, later in 1928, he visited the show cave Endless Caverns, Virginia, publishing his impressions in 1929 in a short travelogue “A Descent to Avernus.” At Endless Caverns, he would have reinforced his understanding that most caves are in limestone, and are often formed by sinking streams; and had experienced what it feels like to travel through a cave: facts which he put to work in AtMoM (and later in the atmosphere of the finely-detailed underground episode in “The Shadow Out of Time”). He could not resist ending his Avernus essay with a typically Lovecraftian flourish that might have surprised the cave’s proprietors:

“And at the bottom of all–far, far down–still trickles the water that carved the whole chain of gulfs out of the primal soluble limestone. Whence it comes and whither it trickles–to what awesome deeps of Tartarean nighted horror it bears the doom-fraught messages of the hoary hills–no being of human mould can say.

“Only They which gibber down There can answer.”

AtMoM refers seven times to “the strange Asian paintings of Nicholas Roerich.” Curious about why Roerich so impressed HPL, I visited the Roerich Museum in Manhattan in 1991. Roerich was–in his own way–as eccentric as Lovecraft, but more cosmopolitan, artistic, and mystical. A number of his paintings were on display, many of them Himalayan-looking mountain scenes showing monastery-like buildings, some with cryptic cave mouths nearby, which could obviously have inspired the scenes in AtMoM. I took the paintings to have been intended to convey transcendent spirituality. Characteristically, however, Lovecraft’s references imputed to them a sinister quality. I asked the Museum receptionist (a Theosophical Society member) if she was aware that the Roerich paintings had been cited by a famous author of horror. She had not, and seemed to be offended by the idea.

The flaws I see in AtMoM are matters of logistical plausibility. That Lake should set up his fossil-hunting drill on a sandstone outcrop, then unexpectedly strike a limestone layer with an extensive open cavern system, in turn filled with fossils spanning a hundred million years or so–not to mention several dormant Old Ones–is extremely improbable. Even in very cavernous terrain, random drilling will only seldom strike a cave. And the fossils in caves–aside from those weathered out of the host limestone or from a prior cave-forming episode–almost always represent only a relatively short period since the cave originated. Lake’s team was unbelievably lucky (albeit the luck had its bad side).

I admire Lovecraft for enhancing the reality of his Antarctic aliens by describing them in exact, non-human anatomical detail, in an era when absurdly humanoid characters (such as “ridiculous oviparous princesses”–as Fritz Leiber put it–on E. R. Burroughs’ Mars) were more the norm in the pulps (and still are, in Star Trek and Star Wars). However, it is not very clear what Lovecraft means by calling the radiate Old Ones “half-vegetable.” The central property of “vegetables” is nutrition by photosynthesis, but for photosynthesis to provide significant nourishment for large, active, moving organisms is not likely. Perhaps their “vast membraneous wings” had chlorophyll? But more likely, being tough and rather woody is all that was meant.

The biggest problem: too much happens in less than 24 hours when Dyer and Danforth have flown to the Old Ones’ abandoned city. Dyer says “I still wonder that we deduced so much in the short time at our disposal.” So do I! The two explorers, hurrying through galleries lined with bas-reliefs, manage to digest pages’ worth of the builders’ history, solely by interpreting these sculptural pictures–even though their creators were not only of a different race and culture, but an utterly alien species! The archaeologists who have struggled for centuries with Egyptian hieroglyphs and Mayan inscriptions would be apoplectic with envy. On top of that, D. & D. have time to descend partway into the cave adjoining the city before fleeing for their lives from living shoggoths. The episode shouldn’t work. Yet, somehow, the power of the narrative is such that the reader is swept along with the scientists, and has to slow down and read critically to notice the improbability.

However that may be, it’s refreshing that Lovecraft has here transcended his racism in the celebrated passage expressing Dyer’s developing admiration of the Old Ones: “Radiates, vegetables, monstrosities, star-spawn–whatever they had been, they were men!”

The cavern of the shoggoths–whose pattern, like the inner world in “The Mound,” suggests possible influence from knowledge of Carlsbad Cavern–is actually more believable today than it would have been in Lovecraft’s time. The giant blind white cave penguins would have seemed impossible in the 1930s. But in recent decades, various caves fed by rising sulfurous water have been found to have sunless ecosystems based on microbial oxidation of sulfides and other minerals. One could now postulate reasonably that HPL’s underground Antarctic sea–said to be warmed by the earth’s internal heat–had such an ecosystem, and that the penguins fed on its smaller creatures, perhaps having evolved dolphin-like echolocation to locate prey. Even the stench in the cave could be, not only the vile reek of shoggoths, but in part the putrid stink of natural hydrogen sulfide. Furthermore, Lovecraft’s adoption of the then-new theory of continental drift for this story was fortuitous in hindsight, though the idea was widely criticized at the time, and the mechanism (plate tectonics) would not be understood until thirty years later.

While casting this story as science fiction, HPL has not forgotten to link the science to extreme and ominous horror. The climax shows Lovecraft at his masterly best. Flying away from the radiates’ city, Danforth screams wildly as he gets a momentary glimpse of a mirage in which are reflected distant, vastly more terrible things beyond the farther mountains; things which even the powerful Old Ones themselves had “shunned and feared”:

“[Danforth] has on rare occasions whispered disjointed and irresponsible things about “the black pit,” “the carven rim,” “the proto-shoggoths,” “the windowless solids with five dimensions,” “the nameless cylinder,” “the elder pharos,” “Yog-Sothoth,” “the primal white jelly,” “the colour out of space,” “the wings,” “the eyes in darkness,” “the moon-ladder,” “the original, the eternal, the undying,” and other bizarre conceptions; but when he is fully himself he repudiates all this and attributes it to his curious and macabre reading of earlier years.”

Dyer wishfully opines that “He could never have seen so much in one instantaneous glance.” But the reader knows better, and the horror is conveyed not only via the inferences inherent in the scene described, but even more in Danforth’s emotional breakdown in reaction to it, and in Dyer’s anxious urge to deny its truth. If Danforth was driven to near- madness by that momentary hint of primal ghastliness–not even seen directly but in fleeting image from tens of miles off–how blastingly, lethally frightful the actual source of that mirage must be! For all its seeming excess, I consider this the most skillful evocation of alien horror I’ve ever read–no Gothic triteness here. No wonder Dyer is so desperate to keep the Miskatonic Expedition from being followed up! HPL uses the same technique to great effect in Edward Derby’s “pit of the shoggoths” hysteria in the later story “The Thing on the Doorstep.”

AtMoM is respected enough by modern scientists that paleontologist John Long’s team, looking for actual fossils in Antarctica, read AtMoM to each other aloud in their tents at night; and Long named his 2001 book about the expedition Mountains of Madness in honor of Lovecraft’s classic story. I believe that HPL would have been extremely pleased by such vindication of his work.

@@.-@: I’ve never read Campbell’s “Who Goes There?” But the Preston & Childs thriller The Ice Limit shows obvious influence from both At the Mountains of Madness (a setting near–though not quite in–Antarctica) and “The Colour Out of Space” (an alien meteorite of unplaceable color and world-threatening capabilities). Those writers have many little homages to HPL in their books.

@@.-@ & 7: Whether Campbell was influenced primarily by Lovecraft remains a matter of debate: I recall Robert M. Price believes that but I don’t think Campbell said one way or the other. The plot of “Who Goes There?” is a “Don A. Stuart” reworking of an earlier, rather less serious, Campbell story, “The Brain Stealers of Mars” (in The Planeteers).

Count me in with those who just love the slow build-up that we get in “Mountains.”The density of detail, the latinate jargon, the golden age of Antarctic exploration….I could read a thousand pages of this kind of stuff. Some random comments/observations:

Lovecraft as Poe scholar:

“Puffs of smoke from Erebus came intermittently, and one of the graduate assistants—a brilliant young fellow named Danforth—pointed out what looked like lava on the snowy slope; remarking that this mountain, discovered in 1840, had undoubtedly been the source of Poe’s image when he wrote seven years later of

—the lavas that restlessly roll

In the ultimate climes of the pole—

In the ultimate climes of the pole—

In the realms of the boreal pole.””

In the realms of the boreal pole.””

Their sulphurous currents down Yaanek

That groan as they roll down Mount Yaanek

If memory serves,Professor Thomas Ollive Mabbott noted that HPL was the first person to figure out that Poe was referring to Mt Erebus.

“and will understand when I speak of Elder Things supposed to have created all earth-life as jest or mistake.”: The Lovecraftian cosmos captured in a single line.

Influence on: Quite a bit. John W Campbell might have hated HPL’s prose-style, but one can detect echoes of “Mountains” in “Who Goes There.” Of course, the tone is radically different, Campbell being a staunch human chauvinist.

Then there’s Ridley Scott’s rather disappointing “Alien” sequel, “Prometheus.” Frankly, huge chunks of the plot for that film read as though they were lifted straight from “Mountains.”

The ongoing adventures of Arthur Gordon Pym: And if anyone wants to read a really fun book that combines Black American literature, “The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym,” and “At the Mountains of Madness,” I strongly recommend “Pym” by Mat Johnson (author of Incognegro, Hunting in Harlem, etc.

I spend this whole story going back and forth between “I will go there now and make a career out of those bas reliefs!!!” and “That is not how geology does the thing!!!!” The latter is not entirely fair, as continental drift was just barely a theoretical glimmer at the time, but it still throws me out of the story. Especially as Lovecraft continually points out how miraculous the city’s preservation is–when you’re palming a card, it’s not wise to shout, “It’s just like someone palmed a card!”

Ahem. Anyway, the aliens are awesome. Though I don’t mark this as Lovecraft “getting over his racism,” given that the so-very-sympathetic, just-like-us Old Ones keep chattel slaves. More on that next week, as I shall avoid putting my entire commentary on Chapters 5-8 in this comment.

Instead, shameless plugs: Anne’s new book, Fathomless, is out today. It has Deep Ones and shoggoths and teenagers trying to wrangle the forces of cosmic indifference. And if you haven’t read Summoned yet, you should. It has undying sorcerers and creepy library books and teenagers trying to wrangle the forces of cosmic indifference, and is excellent stuff.

And on my end of things, the first Aphra Marsh novel will come out from the Tor.com imprint in early 2017. It has body-snatching sorcerers and restrictive library policies and Deep Ones trying to wrangle the forces of cosmic (and human) indifference.

@ellynne: Yes, I felt the same way about the poor radiates. Yes, they kept chattel slaves, yes, they probably had other awful traits–but from their perspective they entered dormancy and woke up to find themselves in a bleak post-apocalyptic future with no possibility of escape. Also, yeah, “Good morning! Something vivisected one of you while you were out. Have a nice day!”

@@@@@ 10 R.Emrys:”Though I don’t mark this as Lovecraft “getting over his racism,” given that the so-very-sympathetic, just-like-us Old Ones keep chattel slaves. More on that next week, as I shall avoid putting my entire commentary on Chapters 5-8 in this comment.”

Don’t want to jump ahead either, but I will note that the Shoggoths are (If a remember correctly-I’m re- reading this in the assigned order) an artificially created species, essentially protoplasmic robots.Hence, I’ve always been somewhat inclined to read their revolt against the Old Ones as a variation on the familiar “Rise of the Machines” scenario.Man’s technology turns against him, etc. Of course, that kind of plot can also be read in a racialized context (cf BLADERUNNER, Asimov’s “Caves of Steel” and “The Naked Sun,” etc), so the one does not rule out the other

More Mountains, More Madness: Edgar Allan Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket has a couple of unauthorised sequels from the 19th century: the most famous is Jules Verne’s An Antarctic Mystery, with its mysterious Sphinx of the ice fields while Charles Romeyn Dake’s A Strange Discovery depicts an ancient Antarctic civilization (whose origin will seem dispiritingly mundane to Lovecraft fans).

Has anyone ever: used a Roerich painting on the cover of James Hilton’s Lost Horizon?

I’ve always loved the image of the scientists happily working on their career-making find, while just behind them Lovecraft describes the protrusions on the radiates’ heads slowly unfolding one by one. That, plus the obvious Evil Detecting Dogs, makes you want grab the characters and shout: “You idiots! They’re just frozen! THEY’RE WAKING UP!”

@13 SchuylerH”;More Mountains, More Madness: Edgar Allan Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket has a couple of unauthorised sequels from the 19th century: the most famous is Jules Verne’s An Antarctic Mystery, with its mysterious Sphinx of the ice fields”

Gotta say, I’ve always thought that Verne’s magnetic Sphinx was a real let-down. Of course, Poe’s “screen goes white” ending is so evocative that it’s hard to think of any ending that wouldn’t feel anti-climactic in comparison:

“March 22d.-The darkness had materially increased, relieved only by the glare of the water thrown back from the white curtain before us. Many gigantic and pallidly white birds flew continuously now from beyond the veil, and their scream was the eternal Tekeli-li! as they retreated from our vision. Hereupon Nu-Nu stirred in the bottom of the boat; but upon touching him we found his spirit departed. And now we rushed into the embraces of the cataract, where a chasm threw itself open to receive us. But there arose in our pathway a shrouded human figure, very far larger in its proportions than any dweller among men. And the hue of the skin of the figure was of the perfect whiteness of the snow.”

@13:”More Mountains, More Madness: Edgar Allan Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket has a couple of unauthorised sequels from the 19th century: the most famous is Jules Verne’s An Antarctic Mystery, with its mysterious Sphinx of the ice fields”

Gotta say, I’ve always thought that Verne’s magnetic Sphinx explanation was a real let-down. Of course, Poe’s “screen goes white” ending is so hauntingly evocative that just about any explanation would feel anti-climactic:

“March 22d.-The darkness had materially increased, relieved only by the glare of the water thrown back from the white curtain before us. Many gigantic and pallidly white birds flew continuously now from beyond the veil, and their scream was the eternal Tekeli-li! as they retreated from our vision. Hereupon Nu-Nu stirred in the bottom of the boat; but upon touching him we found his spirit departed. And now we rushed into the embraces of the cataract, where a chasm threw itself open to receive us. But there arose in our pathway a shrouded human figure, very far larger in its proportions than any dweller among men. And the hue of the skin of the figure was of the perfect whiteness of the snow.”

annathepiper @@@@@ 2: There certainly were some Lovecraftesque monsters in VOYAGE TO THE BOTTOM OF THE SEA. I remember a cousin of the Creature of the Black Lagoon that got loose on board the sub. Of course, he slammed Kowalski into a bulkhead, but Kowalski never minded that kind of thing. He refused to be a deathspian. And wasn’t there something like a giant sea anemone?

My VOYAGE/MYTHOS crossover will feature Kowalski, Admiral Nelson and Captain Crane captured by Deep Ones, who want to marry them off to a trio of scaly but charming Deep Princesses. Mayhem and merriment follow.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 4: I thought of “Who Goes There,” too. And THE THING movies, the earlier one not so much, except for the Thing’s plant-like reproduction. The later one has some horrors HPL would have enjoyed, such as the spider-legged disembodied head.

dgdavis @@@@@ 7: Ooh, ooh, THE ICE LIMIT! I love that book, and did you notice that Pendergast’s nefarious ancestor has a similar meteorite in the Riverside Drive mansion?

Nah, I’d still choose Y’ha’nthlei. But this story is fun to read as a paleontology and invertebrate fan.

George R.R. Martin did homage to Lovecraft once again (or something) by giving Essos an Isle of Leng, ruled by “god-empresses” and said to have underground cities inhabited by “Old Ones”: http://awoiaf.westeros.org/index.php/Leng . I was more amused by his co-opted version of “Ib,” though.

Is tor.com having problems? I can’t view (or post) comments when accessing it on my computer instead of my phone.

Getting comments to appear on a desktop is simply awful, worse in some browsers than others, but never great.

If memory serves,Professor Thomas Ollive Mabbott noted that HPL was the first person to figure out that Poe was referring to Mt Erebus.

But moving it from the South to the North Pole (austral to boreal) presumably so it would fit the metre better.

And, yes, “Mountains of Madness” remains my favourite… the Antarctic, back then, was like outer space in the 1950s and 60s – somewhere isolated, hostile and unknown, but accessible (with the right combination of grit and technology) where adventures could happen. Lovecraft’s explorers are astronauts in all but name.

@16: Poe achieved one of the first (and still one of the best) slingshot endings in Arthur Gordon Pym. No wonder Verne and Dake couldn’t capture that lightning in a bottle.

@2 & 17: I don’t know, I think that the best aquatic creature involved in Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea was a Sturgeon:

The Cosmic Horror of John Carpenter: at Strange Horizons.

Happy birthday to you, happy birthday to you, happy birthday dear: Edward P. Berglund (1942), whose The Disciples of Cthulhu was the first all-original Mythos anthology.

@17 Anne: Are you thinking, perhaps, of the crab monster in VttBotS? That’s the most Lovecraftian monster I can think of off the top of my head. But it’s been so long since I saw the show, that I had forgotten Kowalski and his special relationship with the bulkheads. I remembered him once you mentioned it, though.

The Thing in its various incarnations is based on “Who Goes There?”, so no wonder that you thought of both. Mind you, the one featuring James Arness as a homicidal carrot bears almost no relation to the original story. I’m surprised Campbell got any credit at all.

My laptop has decided it is allergic to Disqus, so while dithering over whether to try Firefox and see if that helps, I am at the library. “Mts of Madness” took my breath away when I was 17–spec. the scene where the plane tops the pass. Now, though, I think that at that height they should have been using oxygen masks–I now don’t recall whether that was included or not. Anyway, around the turn of the 90’s someone did a very expensive illustrated edition that I don’t think anyone could afford and I don’t know what happened to it despite I wrote to the publisher and told them that pricing it out of everyone’s range was counterproductive. More recently, Culbard’s graphic novel I would say is very nicely done–like the rest of his work–except I did not expect the buildings of the city to *all* look like rather conventional skyscrapers topped by Tibetan monuments.

The collection “Madness of Cthulhu” contains sequels/spinoffs, as do others that the interlibrary loan system hasn’t yet gotten hold of for me.

Why did it all seem familiar? Because I spent my teen years roaming WWII ruins in a remote, stormy part of the world, and some of them were decidedly spooky [until I got used to them…]

@Angiportus — Maybe the Donald Grant edition with illos. by Fernando Duval?

http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?3282

Now I’m also coveting that edition.

Okay, I’m confessing to what is probably rank blasphemy here; while I definitely admire the literary craftsmanship of At the Mountains of Madness, it’s not one of my favourite Lovecraft works or even in the top five. I dunno. It just didn’t “grab” me the way some of his other writings did (“The Colour Out of Space,” for instance).

I saw John Carpenter’s The Thing years before I read any Lovecraft (yes, my mom let me watch horror movies at a very early age, on which we can now “blame” my present tastes in literature) :P and when I read At the Mountains of Madness I immediately made that mental connexion. As I understand it, even now, the polar regions aren’t terribly well-explored due to the, um, INCREDIBLE FREEZING COLD.

@Ruthanna: I’ve read a little bit about that star as well but I’m withholding an opinion until scientists have more data. I’ve not been a scientist for quite some time now (having left astrophysics for English, as I believe I mentioned on earlier posts), but I remember enough of my science background to know that any observational astronomical results are still iffy at best. While it is a VERY good bet that there is intelligent life out there besides us (just plug the numbers into the Drake Equation), I’m not yet convinced that this is an example of that. But it’s still exciting to consider! :))

@anne: I DO NOT UNDERSTAND THE LOVECRAFTIAN PENGUIN-HATE. Penguins are *adorable!* I still lived in Boston when the Boston Aquarium had its miniature blue penguin exhibit. If I recall correctly, the ad campaign ran something like: “Yes, they are tiny and blue. No, you can’t have one.” :P (Full disclosure: I went to the exhibit and TOTALLY wanted to steal one!)

@SchuylerH: I thought I was about the ONLY person who has read Lost Horizon! While it’s a problematic book by 2015 standards, I admire how Hilton draws the reader into the narrative just as the main character is drawn into the world of Shangri-La. I remember how much, upon my first reading, I hoped he’d been able to go back and find it again!

I have some thoughts about the slavery of the Shoggoths but I’ll hold off until next week.

Happy Halloween//Samhain/Day of the Dead, everyone! :D I will be at a Halloween-themed costume wedding in upstate NY not too far away from Sleepy Hollow! :)

PS: Anyone know if Del Toro is going to ever make his film version of this story? I know it’s been his “dream project” for a long time.

I DO NOT UNDERSTAND THE LOVECRAFTIAN PENGUIN-HATE. Penguins are *adorable!*

Well, it’s fair to say Lovecraft had a lot of strange hate/fear responses, including but not limited to:

frogs

three-quarter full moons

mirrors

cold climates

hot climates

damp climates

mirrors

the darkness

his relatives

drumming

world music generally but especially flutes

old buildings

underground places

archaeology

swamps

poor people

foreign people

foreign languages

swarthy people

partly-swarthy people

people who lived in the country

people on drugs

exotic seafood

… so it’s not that incongruous to add

penguins

to the list.

Working out an evening out that would antagonise HP Lovecraft in as many ways as possible is left as an exercise for the reader. I’m thinking “get some sushi, then meet Cletus and his girlfriend Balvinder down at the Peruvian jazz bar near the docks!” The penguins are proving trickier.

I try to think of the penguins as an attempt to take something generally seen as cute or funny and making it a thing of horror. Like getting cosmic dread out of tiny kittens. Think about some of those crested penguins with the goofy feathers on their heads. What if those were, say, tentacles? We’ll get to the penguins eventually, but 6-foot tall albino cave penguins could be pretty creepy. And people were probably a lot less familiar with penguins in HPL’s day. Nowadays, they’re a zoo staple and all those movies and TV documentaries from Jacques Cousteau to National Geographic and onwards have made them fun.

@26: Alas, Del Toro’s AtMoM is probably never going to happen. He insists on being able to make an R-rated movie, but the studios all insist on nothing higher than PG-13. It’s a pity, because I think he’s the best chance for a major HPL film that is true to its source material.

@22: According to Vincent Di Fate, Campbell thought that The Thing from Another World was a fine film in its own right but was very disappointed that it deviated so greatly from “Who Goes There?”. I wonder what Campbell would have thought about Carpenter’s version…

@26: I hope he gets the chance but after the weaker-than-expected opening of Crimson Peak, I’m afraid it doesn’t seem all that likely in the near future.

Comanchean: is a rather archaic way of referring to the early Cretaceous.

Concerning penguins: recent discoveries indicate that the Cenozoic really was populated with giant penguins such as inkayacu. Doubtless Lovecraft would have found these even more terrifying than regular penguins. (I have seen African and Humboldt penguins in zoos: they did not send me into paroxysms of terror.)

Pengins: There’s no reason why you couldn’t hybridize penguins and terror birds, right? Aside from common sense and the well-being of the human race, of course.

Lovecraft’s fears: I did once list these out to the tune of “My Favorite Things” (“These are a few of the scariest things…”) Dunno where that got to…

Possible aliens: Intellectually, as a scientist, I’m withholding judgment. Emotionally, as a scientist, I am bouncing up and down asking, “Are we there yet? Are we there yet?”

Restrictive library policies? Now, that’s scary!

Congrats to you both on the new novels.

ATMoM is in so many ways a classic, and one that (as others have noted) has spawned a legion of other works.

If you’re a fan of Ernest Shackleton and At The Mountains of Madness, you might want to check out a novella that fills in the space between: in The Elder Ice (set in Shackleton’s native London in 1924 just after his death) we discover the real reason for the explorers his fascination with Antarctica — and what he brought back…

Penguins, hmmm. Well, not everyone thinks they’re adorable. As in the classic blog, FU Penguin, which points out how cunningly manipulative and incurably self-centered and smug the little bastids are. I myself am more in the “I could watch you waddle and sled on your fat tummy and then swim like all get out forever. Plus how you hold your egg on your feet” school.

David Hambling @@@@@ 32 The Elder Ice sounds luscious!

And if anyone wants to read a deliriously gonzo mash-up of ARTHUR GORDON PYM with AT THE MOUNTAINS OF MADNESS, I heartily recommend Rudy Rucker’s THE HOLLOW EARTH, where Poe voyages to Antarctica and encounters the Old Ones, and much else besides:

“In 1836, Mason Algiers Reynolds leaves his family’s Virginia farm with his father’s slave, a dog, and a mule. Branded a murderer, he finds sanctuary with his hero, Edgar Allan Poe, and together they embark on an extraordinary expedition to the South Pole, and the entrance to the Hollow Earth. It is there, at the center of the world, where strange physics, strange people, and stranger creatures abound, that their bizarre adventures truly begin.”

http://www.amazon.com/The-Hollow-Earth-Rudy-Rucker/dp/1932265201

At the Mountains of Madness was the first Lovecraft story I ever read, and is still one of my favorites. One of the things that really strikes me about it is that, tho a lot of the scientific/technical stuff has dated badly or relies on ridiculously improbably coincidence, at the time, this wasn’t just horror, it was pretty serious hard Sci-fi. It actually holds up much better as Sci-fi than a lot of stuff from the same time period that was intended as Sci-Fi.

And this is also one of those stories where I totally want to see it told from the other side as well. The story of the Old Ones waking up from their long sleep and struggling to deal with the changes that the aeons have wrought.

I found this re-read about a month ago; I’ve finally got up-to-speed and can join the discussion!

One of my favourite Lovecraft stories. Like Anne, I’m in love with the thought of polar exploration, and I think reading this story as a teen played a large part in that. (I’m also very fond of Clark Ashton Smith’s prose poem “The Muse of Hyperborea”, should be available online.)

Re the penguins, I agree with DemetriosX at 28. Various wild animals have been kind of commoditised for us through nature programs, zoos, wildlife photography etc. in the decades since Lovecraft’s death. But even today, I think there’s a difference between seeing a penguin in a zoo or a TV program (sympathetic and kind of funny) and coming across human-sized, albino penguins after a tense trek through a completely alien environment. In the latter situation, the idea of “penguin” would succumb to the idea “frickin’ eerie”.

And good going on the Aphra Marsh novels! I still haven’t read all of Litany of Earth, but I’m greatly enjoying it so far. The narrative voice is perfect.

@anne

I’ve been in love with Antarctica ever since.

So what you’re saying is that to win your affection one has to repeatedly try to kill you or someone dear to you…

Six foot tall, 200 pound penguins were real. Even better they had longer beaks for spearing fish and lived before the glaciation of Antarctica. Tekeli-li!