Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “The Man of Stone,” a collaboration between Lovecraft and Hazel Heald, published in the October 1932 issue of Wonder Stories. You can read it here.

Spoilers ahead!

“March 16—4 a.m.—This is added by Rose C. Morris, about to die.”

Jack, our narrator, introduces his friend Ben Hayden, an aficionado of the bizarre. Hayden has heard from a mutual acquaintance about two strangely life-like statues near Lake Placid, New York. Say, didn’t the realist sculptor Arthur Wheeler disappear in that section of the Adirondacks? Hayden and Jack had better investigate.

They arrive in the rustic village of Mountain Top and quiz loafers at the general store. None are eager to talk about Wheeler, though one garrulous old fellow tells them the sculptor lodged with “Mad Dan” up in the hills. Could be Dan’s young wife and Wheeler got too cozy, and Dan sent the city feller packing. Dan’s no one to interfere with, and now he’s so moody he and his wife haven’t appeared in the village for a while.

Warned to keep away from the uncannier hills, our heroes head in that direction the next day. They have a map to the cave where their acquaintance found the statues, and when they find it, they see he wasn’t exaggerating. The first statue, at the cave mouth, is a dog too realistically detailed for even Wheeler’s skill. Hayden figures it was the victim of incredibly sudden petrification, maybe due to strange gases from the cave. Inside the cavern is a stone man, dressed in actual clothes. Our heroes cry out at its face, which is Arthur Wheeler’s.

Hayden’s next move is to seek out Mad Dan’s cabin. No one answers his knocks, but he and Jack enter via the window of Wheeler’s makeshift studio. Another horror awaits them in the dusty-smelling kitchen: two more stony bodies. An old man sits bound with a whip into a chair, and a young woman lies on the floor beside him, her face permanently frozen in an expression of sardonic satisfaction. Must be Mad Dan and his wife, and what’s this notebook carefully set in the middle of the table?

Hayden and Jack read the notebook before calling the authorities. The public has seen a sensationalized version of it in the cheap newspapers, but they can tell the real story. First, though, know that their nerves have been shaken, as have those of the authorities, who destroyed a certain apparatus found deep in the cave and also many papers from Mad Dan’s attic, including a certain old book.

Most of the notebook is in the cramped handwriting of Dan Morris himself. Let the ignorant villagers call him mad—he’s actually the scion of a long line of wizards, the Van Kaurans, and has inherited their powers and their Book of Eibon, too. He sacrifices to the Black Goat on Hallows Eve and would do the Great Rite that opens the gate, except the damn villagers prevent him. Well, he got along pretty well with his wife Rose, even though she balked at helping him with his rites. Then Arthur Wheeler boarded at his cabin and started making eyes at her.

Dan vows to do away with the sneaking cheats and consults the Book of Eibon for suitably torturous methods. Emanation of Yoth—nah, shopping for child’s blood attracts attention. The Green Decay, too smelly. Wait, what’s this manuscript insert detailing how to turn a man into stone? Too deliciously ironic.

Dan produces his petrifying potion in the cave near his cabin. He experiments with birds and Rose’s beloved dog Rex. Success! Wheeler, lured to the cave, is the next victim, for he readily accepts a swig of potion-doctored wine. Rose isn’t so easy to poison. She refuses to drink Dan’s wine until he’s forced to lock her in the attic and to introduce much lower doses in her drinking water. From the way she begins to limp and crawl, paralysis is setting in, but it takes so long that Dan is getting worn out with anxiety.

The last portion of the notebook is in a different hand—Rose’s. She has freed herself from the attic and bound the sleeping Dan into his armchair with his whip. After reading his notebook, she knows all, but she already suspected that Dan murdered Arthur Wheeler, who meant to help her divorce so they could marry. Dan must have used wizardry to get a hold over her mind and her father’s, or she’d never have wed him, never have submitted every time she tried to escape and he dragged her back to his cabin. Their union has been nothing but abuse for her; worse, Dan has tried to make her do blasphemous rites with him, rites too horrible to describe. She took only a sip of the water he gave her in her attic prison. Even that was enough to half-paralyze her, but she retains strength and mobility enough to force his own potion down Dan’s throat. He turns at once to stone, a fitting end. With Arthur gone, Rose writes that she’ll drink the remaining potion herself. Bury her “statue” with Arthur’s, and put poor petrified Rex at their feet. As for Mad Dan, she doesn’t care what happens to his stony remains.

What’s Cyclopean: Perhaps due to Heald’s influence, the adjectives are kept to a dull roar. There are sinister abnormalities, but nothing cyclopean, rugose, or even gibbous.

The Degenerate Dutch: What else could the Van Kaurens possibly be?

Mythos Making: Dan swears by everything from Shub-Niggurath and Tsathagua to R’lyeh—and there are some definite hints that he may know just a little about another group that lurks in the Catskills.

Libronomicon: The Book of Eibon can tell us many things we don’t want our neighbors to know.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Mad Dan is aptly named, though not (or not only) for the reasons his neighbors seem to think.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Oh, Rose.

And, oh, Hazel. The Heald collaborations are all new to me on this read-through, and I’ve not been disappointed yet. Every one carries the most minor of reputations, if that, and every one ranks with the top tiers of Lovecraft’s solo work. And they have some amazing touches, that appear nowhere else and must be Heald’s own. Fine touches of realism and motivation that add depth to the weirdness, ranging from amusingly apt trivialities—the narrator’s complaints about bad science reporting in “Out of the Aeons”—to horrors far more urgent than a few cosmic monsters.

It’s the latter that make this story stand out. It’s Rose’s predicament, slowly revealed even while the more overtly terrible petrification is accepted nearly from the start. Lovecraft, on his own, would likely have had Mad Dan motivated solely by… well, what explanation is really needed when the rural Dutch do terrible things in the name of inhuman gods? But that’s not enough for Heald, who makes the man an all-too-realistic self-aggrandizing abusive goat turd (I’m trying to be polite here), who’d be just as glad to use negging as mind control spells, if it got him what he wanted. He’s familiar, is what I’m saying, and the fact that he swears by Shub-Niggurath rather than some more popular deity is merely a matter of convenient symbol-set. Which makes him a lot scarier than most of Lovecraft’s bad guys.

And Rose. Oh, Rose. She gets something that very few of Lovecraft’s women get: she gets a voice. And not just the generic voice of the nearest available witness to events. This is the diary that was missing in “Thing on the Doorstep”—Asenath no longer erased, her horror no longer hidden in negative space. Rose isn’t inserted to motivate the men. This story is ultimately hers—witnessed and reported at a remove like any other Lovecraft non-narrator, but hers. And unlike most of those non-narrators, I care what happens to her. I wish she hadn’t closed her story so neatly.

The other details work well, too, even the ones that are standard Lovecraftian furniture. The just-friends-no-really Damon-and-Pythias couple who uncover the story have a decent motivation to do so, and don’t so much abruptly change their minds when they find it as discover more than they bargained for. And… actually do feel like they might be doing agape rather than just being repressed. The perfect statues are genuinely creepy (even if not as creepy as Dan himself). The Van Kaurens’ marginal notations in their Book of Eibon are believable—and one gets the distinct impression that these are not so much skilled wizard-chemists as people that have made much hay from one lucky (?) literary find. One also gets the impression that there are probably as many recipes for chicken soup and secret floor scrub in those margins as there are cleverly devised potions.

It doesn’t hurt that the setting is familiar—in fact, I’ll be up around New Paltz in a couple of days for Thanksgiving. Often, when Lovecraft writes about a place that I know, it’s either changed so much as to be unrecognizable—or he never managed to see it in any recognizable way in the first place. But a few miles west of New York City, in the rural Catskills… the fall colors are gorgeous, but there are still plenty of isolated caves where you could hide a suspiciously detailed statue. Hypothetically speaking.

I promise to be cautious if anyone offers me wine.

Anne’s Commentary

The point of view in this collaboration is reminiscent of another Arthur—that is, Conan Doyle. Jack and Ben Hayden seem as much Watson and Holmes as Damon and Pythias, the friends of ancient legend who trusted each other so deeply that Damon stood hostage for condemned Pythias, offering to be executed in his place should Pythias not return from saying goodbye to his family. (Pythias did return, though only in the nick of time because pirates captured his ship and tossed him overboard, you know, the classical equivalent of a bad traffic jam.) Hayden’s in charge, Jack his “faithful collie.” I guess Hayden could have gone to Mountain Top on his own, but his narration would probably have been more overbearing than Jack’s, needlessly so since all we need is for someone to discover the statue-corpses and the notebook that tells their story. Whereas Jack couldn’t be sole hero because he’d never have gone to Mountain Top to begin with, not being as hot to solve mysterious mysteries as Hayden. Plus, Jack wouldn’t have had the chutzpah to charge straight up to Mad Dan’s cabin.

So Holmes-Hayden scents game afoot in the coincidence of realistic statues where Arthur Wheeler disappeared. Watson-Jack tags along to record discoveries in an amiable, normal-guy kind of way.

I guess we could have simply jumped into the notebook after a short preface by the coroner, but I kind of like Jack’s chatty travelogue and occult naiveté.

The Book of Eibon (aka Liber Ivonis, Livre d’Eibon) was “discovered” by Clark Ashton Smith in “Ubbo-Sathla.” This “strangest and rarest” tome passed through innumerable translations from the original, which was written in the primordial language of Hyperborea. Lovecraft himself stumbles upon it in “The Haunter of the Dark,” “The Dreams in the Witch House,” and “The Shadow Out of Time.” The Van Kaurans were hotshot, big-time wizards to have a copy all to themselves. I fear it suffered some deterioration in Mad Dan’s leaky attic, but probably nothing the curators at Miskatonic University couldn’t have arrested. Too bad those clumsy cops in New York didn’t know enough to turn the precious grimoire over to MU; burning it was really a crying shame! We might be able to find the Emanation of Yoth and the Green Decay in other Eibons, but that petrification trick was in a handwritten insertion, so alas, probably lost forever, along with the other Van Kauran papers.

Joining the proud ranks of Mythos magicians is Mad Dan Morris, a Van Kauran on his mother’s side. He appears to have good raw ability though nothing like the sophistication of a Joseph Curwen or an Ephraim Waite or a Keziah Mason. In background and current social standing he’s more like Wizard Whateley, inheritor of dread tomes and more dread traditions, but himself pretty much self-schooled, the decadent end of a decayed line. Like Old Whateley, he lives among wild hills and howls out the ancient rites at the proper times of year. Like Old Whateley, he knows the way to open gates that should stay shut; unlike Whateley, he lives in a community that will only stand for so much dark magic. It somehow prevents Dan from doing the “Great Rite.” It also makes him wary of snatching a child, and thus obtaining the blood necessary to make Yoth emanate.

Something else Dan shares with all the (male) magicians in Lovecraft is a proclivity for using and abusing women. Joseph Curwen is the mildest abuser of the lot—though he maneuvers Eliza Tillinghast into marriage by blackmailing her father, he treats her and his daughter Ann with remarkable kindness and respect. Smart man, for it would just be all muahahahaha impolitic to mistreat the progenitors of his line and enablers of his immortality.

Ephraim Waite is much nastier. He steals his daughter’s body, then kills his own carcass, into which she’s been transferred. Insult to injury, he’s not satisfied with his nice new housing because, ewww, girl cooties, the natural inferiority of the female and all that. We have hints that, as Asenath in school, he at the very least leers at other girls. Then he marries poor Edward Derby and makes him even more effeminate than Lovecraft dared to. Because only an effeminate man would put up with a domineering, abusive and ultimately body-snatching wife. Even if the “wife” was really a man in (eww) girl clothing.

Old Wizard Whateley murders his wife, then does to his daughter what I suspect Dan wanted to do with Rose—that is, to make her the feminine pawn in his dealings with the Outer Gods. What could be more unspeakably blasphemous (for Rose) than a husband who wanted her, oh, to sleep with Yog-Sothoth and bear His children? Not to mention possible lesser indignities like prancing naked on hilltops, with or without goatish partners. Lavinia’s kinda-human son is no better than her father, for Wilbur too treats her with contempt and ultimately does away with her.

Oh, and though he wasn’t a wizard, let’s not forget how Zamacona intended to dump T’la-Yub as soon as she got his sorry butt out of K’nyan. Oh, oh, and Red Hook wizard Robert Suydam, who marries Cornelia Gerritsen in order to sacrifice her to Lilith on the wedding night. Not cool, dude.

The introduction of a good-guy love interest for the put-upon woman is new to “The Man of Stone.” So is the bitter triumph of the put-upon woman over her abuser. I wonder if Hazel Heald had a hand in these changes to the usual narrative.

Anyhow, you go, Rose! Rest at peace, if stonily, with Arthur and Rex, and let’s hope somebody took a sledgehammer to Mad Dan.

Next week, enjoy a couple of quick tastes of the Dreamlands with “What the Moon Brings” & “Ex Oblivione”.

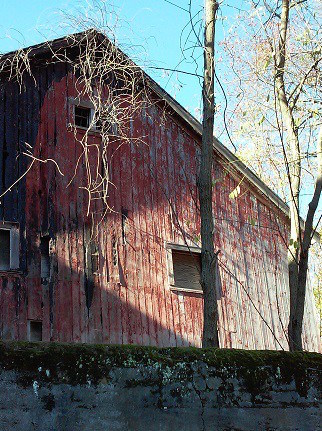

Image: Barn near Riverside Cemetery, Providence. Photo by Anne M. Pillsworth.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in Spring 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and LiveJournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

I can’t help but think of the Heald collaborations as Lovecraft collaborating on fanfiction of his own stories. I don’t recall that any of the She Walks in Shadows contributors brought Rose back, which is a pity.

Wonder Stories: October 1932 also includes Clark Ashton Smith’s “Master of the Asteroid”.

Who Wrote What?: as “The Man of Stone” is the earliest Heald story, more of her prose probably survives in the text than in the later collaborations.

I tend to get thrown out of this story: when Morris uses the phrase “dirty rat”. Far too James Cagney. (I wonder whether Lovecraft or Heald saw the 1932 film Taxi! before writing this: from the dates it’s not impossible.)

An unexpected discovery on Project Gutenberg:

Pedantic interlude: in the re-read index page, several posts aren’t listed in the standard format. They are the posts for “Dagon”, parts I & II of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, part III of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward and part I of “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath”.

I couldn’t remember reading this one at all until I was about halfway through. And even then, all I could recall was that I had read it before. It’s certainly not a forgettable tale.

I wonder if the Heald collaborations are more successful because they were more than just Howard taking on an unwelcome editing/rewrite job for the money. He and Heald had mutual friends in the Eddys and there are indications that she may have been interested in him for more than just his literary talents. In any case, they were probably able to discuss changes and rewrites face to face, which would seem conducive to maintaining the real core of the original.

The van Kaurans (not an actual Dutch name, but perhaps an Americanization of van Keuren) aren’t the only Degenerate Dutch. We get quite a few Dutch names dropped in reference to the local hill families. They might not be worshiping the Elder Gods and performing unspeakable rites, but they are HPL’s seemingly favorite punching bag of rednecks and hillbillies. Note the attitude toward the loafers hanging out at the general store (and yet, did anyone not have a perfect mental image of that ingrained from movies – especially westerns). I think Lovecraft’s classism may be at least as bad as his racism.

I also wonder if the mention of Damon and Pythias was a deliberate feint. By planting a Greek story in our minds, when we first encounter the petrified dog and man, the first thing that springs to mind is Medusa. Then we spend the next chunk of the story waiting for a monster, only to find out that the monster is a vicious abuser already hoist by his own petard.

I remembered this one as a very unremarkable story, something more like Lovecraftian pastiche than original thing. Though it does stand out because of quite active female character (I believe Rose is also the only woman in Lovecraft who eventually gets the role of narrator) and romantic relationship.

Heh, you think Lovecraft’s friend pairs can give impression of repressed queerness? I’m really looking forward your reading of “Hypnos”, aka the story that gets a mention on the TV Tropes page on Ho Yay.

Good mention of the tendency of Lovecraft’s bad guys to mistreat women. I didn’t give this much attention. Of course, modern fiction is full of abusive and misogynist villains, but they seem to be quite a recent trope.

The Lovecraft Insult Generator says Dan is “that chattering, qivering, shadowy, organic blubber.” Not the most accurate, but thorough.

A surprisingly enjoyable tale. I get the impression that HPL got a kick out of using his collaboration/re-write jobs as opportunities to explore stuff that stayed out of his own fiction.Random comments:

@1″ SchuylerH:Who Wrote What?: as “The Man of Stone” is the earliest Heald story, more of her prose probably survives in the text than in the later collaborations.”

If memory serves, I think that HPL told a colleague that about 25% of the prose was Hazel Heald’s.

How we first met: According to Hazel Heald, she was directed Lovecraft’s way by Samuel Loveman. Sadly, her epistolary relationship with HPL seems to have cooled after she started getting tardy with the filthy lucre.

HPL and the distaff side of things: From what I’ve read, C.L. ( Catherine Lucille ) Moore was the living female weird writer that Lovecraft most admired.He read things like “Shambleau” and “Black God’s Kiss” when they first appeared in WEIRD TALES and was greatly impressed.Also, he was the one who, via correspondence, brought Moore and Henry Kuttner together.

In terms of “mainstream/literary” fiction, HPL regarded Proust’s IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME/ REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST as the greatest work of modern times (hardly surprising, given HPL’s temporal concerns). However, among living Anglo novelists, his favorite seems to have been Willa Cather, whose SHADOWS ON THE ROCK was a particular favorite of HPL’s.

@5 trajan23: According to Hazel Heald, she was directed Lovecraft’s way by Samuel Loveman. Sadly, her epistolary relationship with HPL seems to have cooled after she started getting tardy with the filthy lucre.

That’s interesting. Muriel Eddy claims that she was the one who introduced them and tried to fix them up. She and Heald were friends, as were HPL and both Muriel and CM Eddy. CM and Howard were introduced by their mothers and they hung out quite a lot, walking around Providence and elsewhere. Their roaming around Providence provided the background for “Lurker” and attempt to find the Dark Swamp influenced the beginning of “Color”. Muriel also typed up several of Howard’s manuscripts.

I haven’t had much luck trying to find out more about Hazel Heald, though apparently she lived in Somerville, Massachusetts, so sh wouldn’t have been quite so close to HPL as I thought, given her supposed friendship with the Eddys.

As a general rule, I don’t believe Lovecraft’s reports about how much of a given co-authored piece is his work. He clearly resented having to do many of these, or at least saw them as a potential stain on his writerly rep. And to the degree that any reached the point of genuine collaboration rather than massive top-down revision, it would be hard to make the call in any case. He and Heald do seem to be having more fun than many of the other pairs, at least, and it makes them particularly enjoyable.

Speaking of the whiff of suppressed womens’ writing, I have been entirely unable to find anything of Heald’s other than these collaborations. Does anyone know whether she has lost, or difficult-to-track, solo work?

Ruina @@@@@ 3: Hypnos has to come soon; we’re running short on solo work. It’ll have to come on pretty strong, though, to beat out “The Hound” for repressed (or at least unmentioned) homoeroticism.

Trajan23 @@@@@ 5: Not gonna read through Proust on this series, influence or no. Though I will report that my housemate made madeleines for her French class this week, and I was sorely disappointed to taste one with no hypermemetic effect.

Moore, on the other hand, is definitely worth including.

@3 & 7: An excerpt from early on in “Hypnos”:

“So as I drove the crowd away I told him he must come home with me and be my teacher and leader in unfathomed mysteries, and he assented without speaking a word. Afterward I found that his voice was music—the music of deep viols and of crystalline spheres. We talked often in the night, and in the day, when I chiselled busts of him and carved miniature heads in ivory to immortalise his different expressions.”

With C. L. Moore “Shambleau” is the obvious choice; I prefer “Black God’s Kiss” and I see no compelling reason why both couldn’t appear in the reread.

Concerning Heald’s bibliography, the only stories under her name listed in The Supernatural Index are those with Lovecraft. I can’t rule out stories in other (less-thoroughly studied) sources or pseudonymous titles but serious detective work would be needed to find them. (I don’t think Heald kept her letters from Lovecraft, which complicates matters.)

@7 Ruthanna

ISFDB lists only Heald’s 5 collaborations with Lovecraft, a memoir, and two letters to Weird Tales (June and August 1937). She seems to be pretty elusive.

@6 DemetriosX:”That’s interesting. Muriel Eddy claims that she was the one who introduced them and tried to fix them up. She and Heald were friends, as were HPL and both Muriel and CM Eddy. CM and Howard were introduced by their mothers and they hung out quite a lot, walking around Providence and elsewhere. Their roaming around Providence provided the background for “Lurker” and attempt to find the Dark Swamp influenced the beginning of “Color”. Muriel also typed up several of Howard’s manuscripts.”

Don’t have my copy of Joshi’s LIFE handy, so I can’t be absolutely sure, but I certainly seem to recall reading that Heald mentioned Loveman as providing the link to HPL.

As for Muriel Eddy, haven’t there been problems with her recollections, specifically her second (1961) memoir? For example, Joshi notes how there is reason to doubt her story about her husband’s mother meeting HPL’s mother at a woman’s suffrage meeting

@6 DemetriosX:”That’s interesting. Muriel Eddy claims that she was the one who introduced them and tried to fix them up. She and Heald were friends, as were HPL and both Muriel and CM Eddy. CM and Howard were introduced by their mothers and they hung out quite a lot, walking around Providence and elsewhere. Their roaming around Providence provided the background for “Lurker” and attempt to find the Dark Swamp influenced the beginning of “Color”. Muriel also typed up several of Howard’s manuscripts.”

Now I’m starting to wonder if my mental wires didn’t get crossed, and I conflated Heald with Zealia Bishop….

@7: My family used to make tasty chocolate madeleines. If I ever encounter said cookies, they will definitely evoke memories…but so do/would many of the foods we made.

@11: yeah, that’s pretty much what you did.

At first I thought “Wait, so Heald underpaid Lovecraft too”? Sure, he had problems with some of his revision clients, but I didn’t hear about any of such things in Heald’s case.

Hypnos is without question the most homoerotic Lovecraft. Wow.

One reason I keep hoping y’all will do Machen’s The White People is the amazing preteen-girl POV. Machen IMO blew the (very last bit of the) ending, but not the narration itself.

I had not read this Heald-and-Lovecraft. Pretty good, and I agree with the assessment that the narrative was feinting towards a Medusa narrative before going elsewhere.

I do miss the adjectival rush, of how Rose’s rugose lips caught Wheeler’s eye, how he lost his heart to her gibbous smile … how his cyclopean gambrel brows …

FWLIW (and for that matter, how common) Machen’s Inmost Light includes a wife who loses her soul at her husband’s request (in the search for hidden knowledge). It’s also possibly the inspiration for one of the most difficult of the Ijon Tichy stories, the name of which I can’t at this moment remember.

A Thanksgiving message from H. P. Lovecraft: In 1911, Lovecraft and his mother been invited to dinner with the Clarks’: Lovecraft’s response was to leave her this note:

“If, as you start towards Lillies’ festive spread,

You find me snoring loudly in my bed,

Awake me not, for I would fain repose,

And through the day in quiet slumber doze.

But lest I starve, for lack of food to eat,

Leave here a dish of Quaker Puffed Wheat,

Or breakfast biscuit, which, it matters not,

To break my fast when out of bed I’ve got.

And if to supper you perchance should stay,

Thus to complete a glorious festive day,

Announce the fact to me by telephone,

That whilst you eat, I may prepare my own.“

Ooooh, “Shambleau” and “Kiss” please. And I was too late getting this contemporary pic of Dan’s barn to Ruthanna, so below. I think Jack himself is the photographer:

I don’t think Robert Suydam intended to sacrifice his new bride, or himself. I think that he was leaving the cult, having got what he wanted, and they came after him and her.