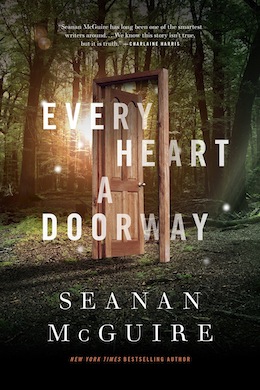

Seanan McGuire’s Every Heart a Doorway—available April 5th from Tor.com Publishing—introduces readers to Eleanor West’s Home for Wayward Children…

Children have always disappeared under the right conditions; slipping through the shadows under a bed or at the back of a wardrobe, tumbling down rabbit holes and into old wells, and emerging somewhere… else. But magical lands have little need for used-up miracle children.

Nancy tumbled once, but now she’s back. The things she’s experienced… they change a person. The children under Miss West’s care understand all too well. And each of them is seeking a way back to their own fantasy world. But Nancy’s arrival marks a change at the Home. There’s a darkness just around each corner, and when tragedy strikes, it’s up to Nancy and her new-found schoolmates to get to the heart of things.

No matter the cost.

Part I

The Golden Afternoons

There Was a Little Girl

The girls were never present for the entrance interviews. Only their parents, their guardians, their confused siblings, who wanted so much to help them but didn’t know how. It would have been too hard on the prospective students to sit there and listen as the people they loved most in all the world—all this world, at least—dismissed their memories as delusions, their experiences as fantasy, their lives as some intractable illness.

What’s more, it would have damaged their ability to trust the school if their first experience of Eleanor had been seeing her dressed in respectable grays and lilacs, with her hair styled just so, like the kind of stolid elderly aunt who only really existed in children’s stories. The real Eleanor was nothing like that. Hearing the things she said would have only made it worse, as she sat there and explained, so earnestly, so sincerely, that her school would help to cure the things that had gone wrong in the minds of all those little lost lambs. She could take the broken children and make them whole again.

She was lying, of course, but there was no way for her potential students to know that. So she demanded that she meet with their legal guardians in private, and she sold her bill of goods with the focus and skill of a born con artist. If those guardians had ever come together to compare notes, they would have found that her script was well-practiced and honed like the weapon that it was.

“This is a rare but not unique disorder that manifests in young girls as stepping across the border into womanhood,” she would say, making careful eye contact with the desperate, overwhelmed guardians of her latest wandering girl. On the rare occasion when she had to speak to the parents of a boy, she would vary her speech, but only as much as the situation demanded. She had been working on this routine for a long time, and she knew how to play upon the fears and desires of adults. They wanted what was best for their charges, as did she. It was simply that they had very different ideas of what “best” meant.

To the parents, she said, “This is a delusion, and some time away may help to cure it.”

To the aunts and uncles, she said, “This is not your fault, and I can be the solution.”

To the grandparents, she said, “Let me help. Please, let me help you.”

Not every family agreed on boarding school as the best solution. About one out of every three potential students slipped through her fingers, and she mourned for them, those whose lives would be so much harder than they needed to be, when they could have been saved. But she rejoiced for those who were given to her care. At least while they were with her, they would be with someone who understood. Even if they would never have the opportunity to go back home, they would have someone who understood, and the company of their peers, which was a treasure beyond reckoning.

Eleanor West spent her days giving them what she had never had, and hoped that someday, it would be enough to pay her passage back to the place where she belonged.

Coming Home, Leaving Home

The habit of narration, of crafting something miraculous out of the commonplace, was hard to break. Narration came naturally after a time spent in the company of talking scarecrows or disappearing cats; it was, in its own way, a method of keeping oneself grounded, connected to the thin thread of continuity that ran through all lives, no matter how strange they might become. Narrate the impossible things, turn them into a story, and they could be controlled. So:

The manor sat in the center of what would have been considered a field, had it not been used to frame a private home. The grass was perfectly green, the trees clustered around the structure perfectly pruned, and the garden grew in a profusion of colors that normally existed together only in a rainbow, or in a child’s toy box. The thin black ribbon of the driveway curved from the distant gate to form a loop in front of the manor itself, feeding elegantly into a slightly wider waiting area at the base of the porch. A single car pulled up, tawdry yellow and seeming somehow shabby against the carefully curated scene. The rear passenger door slammed, and the car pulled away again, leaving a teenage girl behind.

She was tall and willowy and couldn’t have been more than seventeen; there was still something of the unformed around her eyes and mouth, leaving her a work in progress, meant to be finished by time. She wore black—black jeans, black ankle boots with tiny black buttons marching like soldiers from toe to calf—and she wore white—a loose tank top, the faux pearl bands around her wrists—and she had a ribbon the color of pomegranate seeds tied around the base of her ponytail. Her hair was bone-white streaked with runnels of black, like oil spilled on a marble floor, and her eyes were pale as ice. She squinted in the daylight. From the look of her, it had been quite some time since she had seen the sun. Her small wheeled suitcase was bright pink, covered with cartoon daisies. She had not, in all likelihood, purchased it herself.

Raising her hand to shield her eyes, the girl looked toward the manor, pausing when she saw the sign that hung from the porch eaves. ELEANOR WEST’S HOME FOR WAYWARD CHILDREN it read, in large letters. Below, in smaller letters, it continued no solicitation, no visitors, no quests.

The girl blinked. The girl lowered her hand. And slowly, the girl made her way toward the steps.

On the third floor of the manor, Eleanor West let go of the curtain and turned toward the door while the fabric was still fluttering back into its original position. She appeared to be a well-preserved woman in her late sixties, although her true age was closer to a hundred: travel through the lands she had once frequented had a tendency to scramble the internal clock, making it difficult for time to get a proper grip upon the body. Some days she was grateful for her longevity, which had allowed her to help so many more children than she would ever have lived to see if she hadn’t opened the doors she had, if she had never chosen to stray from her proper path. Other days, she wondered whether this world would ever discover that she existed—that she was little Ely West the Wayward Girl, somehow alive after all these years—and what would happen to her when that happened.

Still, for the time being, her back was strong and her eyes were as clear as they had been on the day when, as a girl of seven, she had seen the opening between the roots of a tree on her father’s estate. If her hair was white now, and her skin was soft with wrinkles and memories, well, that was no matter at all. There was still something unfinished around her eyes; she wasn’t done yet. She was a story, not an epilogue. And if she chose to narrate her own life one word at a time as she descended the stairs to meet her newest arrival, that wasn’t hurting anyone. Narration was a hard habit to break, after all.

Sometimes it was all a body had.

* * *

Nancy stood frozen in the center of the foyer, her hand locked on the handle of her suitcase as she looked around, trying to find her bearings. She wasn’t sure what she’d been expecting from the “special school” her parents were sending her to, but it certainly hadn’t been this… this elegant country home. The walls were papered in an old-fashioned floral print of roses and twining clematis vines, and the furnishings—such as they were in this intentionally under-furnished entryway—were all antiques, good, well-polished wood with brass fittings that matched the curving sweep of the banister. The floor was cherrywood, and when she glanced upward, trying to move her eyes without lifting her chin, she found herself looking at an elaborate chandelier shaped like a blooming flower.

“That was made by one of our alumni, actually,” said a voice. Nancy wrenched her gaze from the chandelier and turned it toward the stairs.

The woman who was descending was thin, as elderly women sometimes were, but her back was straight, and the hand resting on the banister seemed to be using it only as a guide, not as any form of support. Her hair was as white as Nancy’s own, without the streaks of defiant black, and styled in a puffbull of a perm, like a dandelion that had gone to seed. She would have looked perfectly respectable, if not for her electric orange trousers, paired with a hand-knit sweater knit of rainbow wool and a necklace of semiprecious stones in a dozen colors, all of them clashing. Nancy felt her eyes widen despite her best efforts, and hated herself for it. She was losing hold of her stillness one day at a time. Soon, she would be as jittery and unstable as any of the living, and then she would never find her way back home.

“It’s virtually all glass, of course, except for the bits that aren’t,” continued the woman, seemingly untroubled by Nancy’s blatant staring. “I’m not at all sure how you make that sort of thing. Probably by melting sand, I assume. I contributed those large teardrop-shaped prisms at the center, however. All twelve of them were of my making. I’m rather proud of that.” The woman paused, apparently expecting Nancy to say something.

Nancy swallowed. Her throat was so dry these days, and nothing seemed to chase the dust away. “If you don’t know how to make glass, how did you make the prisms?” she asked.

The woman smiled. “Out of my tears, of course. Always assume the simplest answer is the true one, here, because most of the time, it will be. I’m Eleanor West. Welcome to my home. You must be Nancy.”

“Yes,” Nancy said slowly. “How did you… ?”

“Well, you’re the only student we were expecting to receive today. There aren’t as many of you as there once were. Either the doors are getting rarer, or you’re all getting better about not coming back. Now, be quiet a moment, and let me look at you.” Eleanor descended the last three steps and stopped in front of Nancy, studying her intently for a moment before she walked a slow circle around her. “Hmm. Tall, thin, and very pale. You must have been someplace with no sun—but no vampires either, I think, given the skin on your neck. Jack and Jill will be awfully pleased to meet you. They get tired of all the sunlight and sweetness people bring through here.”

“Vampires?” said Nancy blankly. “Those aren’t real.”

“None of this is real, my dear. Not this house, not this conversation, not those shoes you’re wearing—which are several years out of style if you’re trying to reacclimatize yourself to the ways of your peers, and are not proper mourning shoes if you’re trying to hold fast to your recent past—and not either one of us. ‘Real’ is a four-letter word, and I’ll thank you to use it as little as possible while you live under my roof.” Eleanor stopped in front of Nancy again. “It’s the hair that betrays you. Were you in an Underworld or a Netherworld? You can’t have been in an Afterlife. No one comes back from those.”

Nancy gaped at her, mouth moving silently as she tried to find her voice. The old woman said those things—those cruelly impossible things—so casually, like she was asking after nothing more important than Nancy’s vaccination records.

Eleanor’s expression transformed, turning soft and apologetic. “Oh, I see I’ve upset you. I’m afraid I have a tendency to do that. I went to a Nonsense world, you see, six times before I turned sixteen, and while I eventually had to stop crossing over, I never quite learned to rein my tongue back in. You must be tired from your journey, and curious about what’s to happen here. Is that so? I can show you to your room as soon as I know where you fall on the compass. I’m afraid that really does matter for things like housing; you can’t put a Nonsense traveler in with someone who went walking through Logic, not unless you feel like explaining a remarkable amount of violence to the local police. They do check up on us here, even if we can usually get them to look the other way. It’s all part of our remaining accredited as a school, although I suppose we’re more of a sanitarium, of sorts. I do like that word, don’t you? ‘Sanitarium.’ It sounds so official, while meaning absolutely nothing at all.”

“I don’t understand anything you’re saying right now,” said Nancy. She was ashamed to hear her voice come out in a tinny squeak, even as she was proud of herself for finding it at all.

Eleanor’s face softened further. “You don’t have to pretend anymore, Nancy. I know what you’ve been going through—where you’ve been. I went through something a long time ago, when I came back from my own voyages. This isn’t a place for lies or pretending everything is all right. We know everything is not all right. If it were, you wouldn’t be here. Now. Where did you go?”

“I don’t…”

“Forget about words like ‘Nonsense’ and ‘Logic.’ We can work out those details later. Just answer. Where did you go?”

“I went to the Halls of the Dead.” Saying the words aloud was an almost painful relief. Nancy froze again, staring into space as if she could see her voice hanging there, shining garnet-dark and perfect in the air. Then she swallowed, still not chasing away the dryness, and said, “It was… I was looking for a bucket in the cellar of our house, and I found this door I’d never seen before. When I went through, I was in a grove of pomegranate trees. I thought I’d fallen and hit my head. I kept going because… because…”

Because the air had smelled so sweet, and the sky had been black velvet, spangled with points of diamond light that didn’t flicker at all, only burned constant and cold. Because the grass had been wet with dew, and the trees had been heavy with fruit. Because she had wanted to know what was at the end of the long path between the trees, and because she hadn’t wanted to turn back before she understood everything. Because for the first time in forever, she’d felt like she was going home, and that feeling had been enough to move her feet, slowly at first, and then faster, and faster, until she had been running through the clean night air, and nothing else had mattered, or would ever matter again—

“How long were you gone?”

The question was meaningless. Nancy shook her head. “Forever. Years… I was there for years. I didn’t want to come back. Ever.”

“I know, dear.” Eleanor’s hand was gentle on Nancy’s elbow, guiding her toward the door behind the stairs. The old woman’s perfume smelled of dandelions and gingersnaps, a combination as nonsensical as everything else about her. “Come with me. I have the perfect room for you.”

* * *

Eleanor’s “perfect room” was on the first floor, in the shadow of a great old elm that blocked almost all the light that would otherwise have come in through the single window. It was eternal twilight in that room, and Nancy felt the weight drop from her shoulders as she stepped inside and looked around. One half the room—the half with the window—was a jumble of clothing, books, and knickknacks. A fiddle was tossed carelessly on the bed, and the associated bow was balanced on the edge of the bookshelf, ready to fall at the slightest provocation. The air smelled of mint and mud.

The other half of the room was as neutral as a hotel. There was a bed, a small dresser, a bookshelf, and a desk, all in pale, unvarnished wood. The walls were blank. Nancy looked to Eleanor long enough to receive the nod of approval before walking over and placing her suitcase primly in the middle of what would be her bed.

“Thank you,” she said. “I’m sure this will be fine.”

“I admit, I’m not as confident,” said Eleanor, frowning at Nancy’s suitcase. It had been placed so precisely… “Anyplace called ‘the Halls of the Dead’ is going to have been an Underworld, and most of those fall more under the banner of Nonsense than Logic. It seems like yours may have been more regimented. Well, no matter. We can always move you if you and Sumi prove ill-suited. Who knows? You might provide her with some of the grounding she currently lacks. And if you can’t do that, well, hopefully you won’t actually kill one another.”

“Sumi?”

“Your roommate.” Eleanor picked her way through the mess on the floor until she reached the window. Pushing it open, she leaned out and scanned the branches of the elm tree until she found what she was looking for. “One and two and three, I see you, Sumi. Come inside and meet your roommate.”

“Roommate?” The voice was female, young, and annoyed.

“I warned you,” said Eleanor, as she pulled her head back inside and returned to the center of the room. She moved with remarkable assurance, especially given how cluttered the floor was; Nancy kept expecting her to fall, and somehow, she didn’t. “I told you a new student was arriving this week, and that if it was a girl from a compatible background, she would be taking the spare bed. Do you remember any of this?”

“I thought you were just talking to hear yourself talk. You do that. Everyone does that.” A head appeared in the window, upside down, its owner apparently hanging from the elm tree. She looked to be about Nancy’s age, of Japanese descent, with long black hair tied into two childish pigtails, one above each ear. She looked at Nancy with unconcealed suspicion before asking, “Are you a servant of the Queen of Cakes, here to punish me for my transgressions against the Countess of Candy Floss? Because I don’t feel like going to war right now.”

“No,” said Nancy blankly. “I’m Nancy.”

“That’s a boring name. How can you be here with such a boring name?” Sumi flipped around and dropped out of the tree, vanishing for a moment before she popped back up, leaned on the windowsill, and asked, “Eleanor-Ely, are you sure? I mean, sure-sure? She doesn’t look like she’s supposed to be here at all. Maybe when you looked at her records, you saw what wasn’t there again and really she’s supposed to be in a school for juvenile victims of bad dye jobs.”

“I don’t dye my hair!” Nancy’s protest was heated. Sumi stopped talking and blinked at her. Eleanor turned to look at her. Nancy’s cheeks grew hot as the blood rose in her face, but she stood her ground, somehow keeping herself from reaching up to stroke her hair as she said, “It used to be all black, like my mother’s. When I danced with the Lord of the Dead for the first time, he said it was beautiful, and he ran his fingers through it. All the hair turned white around them, out of jealousy. That’s why I only have five black streaks left. Those are the parts he touched.”

Looking at her with a critical eye, Eleanor could see how those five streaks formed the phantom outline of a hand, a place where the pale young woman in front of her had been touched once and never more. “I see,” she said.

“I don’t dye it,” said Nancy, still heated. “I would never dye it. That would be disrespectful.”

Sumi was still blinking, eyes wide and round. Then she grinned. “Oh, I like you,” she said. “You’re the craziest card in the deck, aren’t you?”

“We don’t use that word here,” snapped Eleanor.

“But it’s true,” said Sumi. “She thinks she’s going back. Don’t you, Nancy? You think you’re going to open the right-wrong door, and see your stairway to Heaven on the other side, and then it’s one step, two step, how d’you do step, and you’re right back in your story. Crazy girl. Stupid girl. You can’t go back. Once they throw you out, you can’t go back.”

Nancy felt as if her heart were trying to scramble up her throat and choke her. She swallowed it back down, and said, in a whisper, “You’re wrong.”

Sumi’s eyes were bright. “Am I?”

Eleanor clapped her hands, pulling their attention back to her. “Nancy, why don’t you unpack and get settled? Dinner is at six thirty, and group therapy will follow at eight. Sumi, please don’t inspire her to murder you before she’s been here for a full day.”

“We all have our own ways of trying to go home,” said Sumi, and disappeared from the window’s frame, heading off to whatever she’d been doing before Eleanor disturbed her. Eleanor shot Nancy a quick, apologetic look, and then she too was gone, shutting the door behind herself. Nancy was, quite abruptly, alone.

She stayed where she was for a count of ten, enjoying the stillness. When she had been in the Halls of the Dead, she had sometimes been expected to hold her position for days at a time, blending in with the rest of the living statuary. Serving girls who were less skilled at stillness had come through with sponges soaked in pomegranate juice and sugar, pressing them to the lips of the unmoving. Nancy had learned to let the juice trickle down her throat without swallowing, taking it in passively, like a stone takes in the moonlight. It had taken her months, years even, to become perfectly motionless, but she had done it: oh, yes, she had done it, and the Lady of Shadows had proclaimed her beautiful beyond measure, little mortal girl who saw no need to be quick, or hot, or restless.

But this world was made for quick, hot, restless things; not like the quiet Halls of the Dead. With a sigh, Nancy abandoned her stillness and turned to open her suitcase. Then she froze again, this time out of shock and dismay. Her clothing—the diaphanous gowns and gauzy black shirts she had packed with such care—was gone, replaced by a welter of fabrics as colorful as the things strewn on Sumi’s side of the room. There was an envelope on top of the pile. With shaking fingers, Nancy picked it up and opened it.

Nancy—

We’re sorry to play such a mean trick on you, sweetheart, but you didn’t leave us much of a choice. You’re going to boarding school to get better, not to keep wallowing in what your kidnappers did to you. We want our real daughter back. These clothes were your favorites before you disappeared. You used to be our little rainbow! Do you remember that?

You’ve forgotten so much.

We love you. Your father and I, we love you more than anything, and we believe you can come back to us. Please forgive us for packing you a more suitable wardrobe, and know that we only did it because we want the best for you. We want you back.

Have a wonderful time at school, and we’ll be waiting for you when you’re ready to come home to stay.

The letter was signed in her mother’s looping, unsteady hand. Nancy barely saw it. Her eyes filled with hot, hateful tears, and her hands were shaking, fingers cramping until they had crumpled the paper into an unreadable labyrinth of creases and folds. She sank to the floor, sitting with her knees bent to her chest and her eyes fixed on the open suitcase. How could she wear any of those things? Those were daylight colors, meant for people who moved in the sun, who were hot, and fast, and unwelcome in the Halls of the Dead.

“What are you doing?” The voice belonged to Sumi.

Nancy didn’t turn. Her body was already betraying her by moving without her consent. The least she could do was refuse to move it voluntarily.

“It looks like you’re sitting on the floor and crying, which everyone knows is dangerous, dangerous, don’t-do-that dangerous; it makes it look like you’re not holding it together, and you might shake apart altogether,” said Sumi. She leaned close, so close that Nancy felt one of the other girl’s pigtails brush her shoulder. “Why are you crying, ghostie girl? Did someone walk across your grave?”

“I never died, I just went to serve the Lord of the Dead for a while, that’s all, and I was going to stay forever, until he said I had to come back here long enough to be sure. Well, I was sure before I ever left, and I don’t know why my door isn’t here.” The tears clinging to her cheeks were too hot. They felt like they were scalding her. Nancy allowed herself to move, reaching up and wiping them viciously away. “I’m crying because I’m angry, and I’m sad, and I want to go home.”

“Stupid girl,” said Sumi. She placed a sympathetic hand atop Nancy’s head before smacking her—lightly, but still a hit—and leaping up onto her bed, crouching next to the open suitcase. “You don’t mean home where your parents are, do you? Home to school and class and boys and blather, no, no, no, not for you anymore, all those things are for other people, people who aren’t as special as you are. You mean the home where the man who bleached your hair lives. Or doesn’t live, since you’re a ghostie girl. A stupid ghostie girl. You can’t go back. You have to know that by now.”

Nancy raised her head and frowned at Sumi. “Why? Before I went through that doorway, I knew there was no such thing as a portal to another world. Now I know that if you open the right door at the right time, you might finally find a place where you belong. Why does that mean I can’t go back? Maybe I’m just not finished being sure.”

The Lord of the Dead wouldn’t have lied to her, he wouldn’t. He loved her.

He did.

“Because hope is a knife that can cut through the foundations of the world,” said Sumi. Her voice was suddenly crystalline and clear, with none of her prior whimsy. She looked at Nancy with calm, steady eyes. “Hope hurts. That’s what you need to learn, and fast, if you don’t want it to cut you open from the inside out. Hope is bad. Hope means you keep on holding to things that won’t ever be so again, and so you bleed an inch at a time until there’s nothing left. Ely-Eleanor is always saying ‘don’t use this word’ and ‘don’t use that word,’ but she never bans the ones that are really bad. She never bans hope.”

“I just want to go home,” whispered Nancy.

“Silly ghost. That’s all any of us want. That’s why we’re here,” said Sumi. She turned to Nancy’s suitcase and began poking through the clothes. “These are pretty. Too small for me. Why do you have to be so narrow? I can’t steal things that won’t fit, that would be silly, and I’m not getting any smaller here. No one ever does in this world. High Logic is no fun at all.”

“I hate them,” said Nancy. “Take them all. Cut them up and make streamers for your tree, I don’t care, just get them away from me.”

“Because they’re the wrong colors, right? Somebody else’s rainbow.” Sumi bounced off the bed, slamming the suitcase shut and hauling it after her. “Get up, come on. We’re going visiting.”

“What?” Nancy looked after Sumi, bewildered and beaten down. “I’m sorry. I’ve just met you, and I really don’t want to go anywhere with you.”

“Then it’s a good thing I don’t care, isn’t it?” Sumi beamed for a moment, bright as the hated, hated sun, and then she was gone, trotting out the door with Nancy’s suitcase and all of Nancy’s clothes.

Nancy didn’t want those clothes, and for one tempting moment, she considered staying where she was. Then she sighed, and stood, and followed. She had little enough to cling to in this world. And she was eventually going to need clean underpants.

Beautiful Boys and Glamorous Girls

Sumi was restless, in the way of the living, but even for the living, she was fast. She was halfway down the hall by the time Nancy emerged from the room. At the sound of Nancy’s footsteps, she paused, looking back over her shoulder and scowling at the taller girl.

“Hurry, hurry, hurry,” she scolded. “If dinner catches us without doing what needs done, we’ll miss the scones and jam.”

“Dinner chases you? And you have scones and jam for dinner if it doesn’t catch you?” asked Nancy, bewildered.

“Not usually,” said Sumi. “Not often. Okay, not ever, yet. But it could happen, if we wait long enough, and I don’t want to miss out when it does! Dinners are mostly dull, awful things, all meat and potatoes and things to build healthy minds and bodies. Boring. I bet your dinners with the dead people were a lot more fun.”

“Sometimes,” admitted Nancy. There had been banquets, yes, feasts that lasted weeks, with the tables groaning under the weight of fruits and wines and dark, rich desserts. She had tasted unicorn at one of those feasts, and gone to her bed with a mouth that still tingled from the delicate venom of the horse-like creature’s sweetened flesh. But mostly, there had been the silver cups of pomegranate juice, and the feeling of an empty stomach adding weight to her stillness. Hunger had died quickly in the Underworld. It was unnecessary, and a small price to pay for the quiet, and the peace, and the dances; for everything she’d so fervently enjoyed.

“See? Then you understand the importance of a good dinner,” Sumi started walking again, keeping her steps short in deference to Nancy’s slower stride. “Kade will get you fixed right up, right as rain, right as rabbits, you’ll see. Kade knows where the best things are.”

“Who is Kade? Please, you have to slow down.” Nancy felt like she was running for her life as she tried to keep up with Sumi. The smaller girl’s motions were too fast, too constant for Nancy’s Underworld-adapted eyes to track them properly. It was like following a large hummingbird toward some unknown destination, and she was already exhausted.

“Kade has been here a very-very long time. Kade’s parents don’t want him back.” Sumi looked over her shoulder and twinkled at Nancy. There was no other word to describe her expression, which was a strange combination of wrinkling her nose and tightening the skin around her eyes, all without visibly smiling. “My parents didn’t want me back either, not unless I was willing to be their good little girl again and put all this nonsense about Nonsense aside. They sent me here, and then they died, and now they’ll never want me at all. I’m going to live here always, until Ely-Eleanor has to let me have the attic for my own. I’ll pull taffy in the rafters and give riddles to all the new girls.”

They had reached a flight of stairs. Sumi began bounding up them. Nancy followed more sedately.

“Wouldn’t you get spiders and splinters and stuff in the candy?” she asked.

Sumi rewarded her with a burst of laughter and an actual smile. “Spiders and splinters and stuff!” she crowed. “You’re alliterating already! Oh, maybe we will be friends, ghostie girl, and this won’t be completely dreadful after all. Now come on. We’ve much to do, and time does insist on being linear here, because it’s awful.”

The flight of stairs ended with a landing and another flight of stairs, which Sumi promptly started up, leaving Nancy no choice but to follow. All those days of stillness had made her muscles strong, accustomed to supporting her weight for hours at a time. Some people thought only motion bred strength. Those people were wrong. The mountain was as powerful as the tide, just… in a different way. Nancy felt like a mountain as she chased Sumi higher and higher into the house, until her heart was thundering in her chest and her breath was catching in her throat, until she feared that she would choke on it.

Sumi stopped in front of a plain white door marked only with a small, almost polite sign reading keep out. Grinning, she said, “If he meant that, he wouldn’t say it. He knows that for anyone who’s spent any time at all in Nonsense that, really, he’s issuing an invitation.”

“Why do people around here keep using that word like it’s a place?” asked Nancy. She was starting to feel like she’d missed some essential introductory session about the school, one that would have answered all her questions and left her a little less lost.

“Because it is, and it isn’t, and it doesn’t matter,” said Sumi, and knocked on the attic door before hollering, “We’re coming in!” and shoving it open to reveal what looked like a cross between a used bookstore and a tailor’s shop. Piles of books covered every available surface. The furniture, such as it was—a bed, a desk, a table—appeared to be made from the piles of books, all save for the bookshelves lining the walls. Those, at least, were made of wood, probably for the sake of stability. Bolts of fabric were piled atop the books. They ranged from cotton and muslin to velvet and the finest of thin, shimmering silks. At the center of it all, cross-legged atop a pedestal of paperbacks, sat the most beautiful boy Nancy had ever seen.

His skin was golden tan, his hair was black, and when he looked up—with evident irritation—from the book he was holding, she saw that his eyes were brown and his features were perfect. There was something timeless about him, like he could have stepped out of a painting and into the material world. Then he spoke.

“What’n the fuck are you doing in here again, Sumi?” he demanded, Oklahoma accent thick as peanut butter spread across a slice of toast. “I told you that you weren’t welcome after the last time.”

“You’re just mad because I came up with a better filing system for your books than you could,” said Sumi, sounding unruffled. “Anyway, you didn’t mean it. I am the sunshine in your sky, and you’d miss me if I was gone.”

“You organized them by color, and it took me weeks to figure out where anything was. I’m doing important research up here.” Kade unfolded his legs and slid down from his pile of books. He knocked off a paperback in the process, catching it deftly before it could hit the ground. Then he turned to look at Nancy. “You’re new. I hope she’s not already leading you astray.”

“So far, she’s just led me to the attic,” said Nancy inanely. Her cheeks reddened, and she said, “I mean, no. I’m not so easy to lead places, most of the time.”

“She’s more of a ‘standing really still and hoping nothing eats her’ sort of girl,” said Sumi, and thrust the suitcase toward him. “Look what her parents did.”

Kade raised his eyebrows as he took in the virulent pinkness of the plastic. “That’s colorful,” he said after a moment. “Paint could fix it.”

“Outside, maybe. You can’t paint underpants. Well, you can, but then they come out all stiff, and no one believes you didn’t mess them.” Sumi’s expression sobered for a moment. When she spoke again, it was with a degree of clarity that was almost unnerving, coming from her. “Her parents swapped out her things before they sent her off to school. They knew she wouldn’t like it, and they did it anyway. There was a note.”

“Oh,” said Kade, with sudden understanding. “One of those. All right. Is this going to be a straight exchange, then?”

“I’m sorry, I don’t understand what’s going on,” said Nancy. “Sumi grabbed my suitcase and ran away with it. I don’t want to bother anyone.…”

“You’re not bothering me,” said Kade. He took the suitcase from Sumi before turning toward Nancy. “Parents don’t always like to admit that things have changed. They want the world to be exactly the way it was before their children went away on these life-changing adventures, and when the world doesn’t oblige, they try to force it into the boxes they build for us. I’m Kade, by the way. Fairyland.”

“I’m Nancy, and I’m sorry, I don’t understand.”

“I went to a Fairyland. I spent three years there, chasing rainbows and growing up by inches. I killed a Goblin King with his own sword, and he made me his heir with his dying breath, the Goblin Prince in Waiting.” Kade walked off into the maze of books, still carrying Nancy’s suitcase. His voice drifted back, betraying his location. “The King was my enemy, but he was the first adult to see me clearly in my entire life. The court of the Rainbow Princess was shocked, and they threw me down the next wishing well we passed. I woke up in a field in the middle of Nebraska, back in my ten-year-old body, wearing the dress I’d had on when I first fell into the Prism.” The way he said “Prism” left no question about what he meant: it was a proper name, the title of some strange passage, and his voice ached around that single syllable like flesh aches around a knife.

“I still don’t understand,” said Nancy.

Sumi sighed extravagantly. “He’s saying he fell into a Fairyland, which is sort of like going to a Mirror, only they’re really high Logic pretending to be high Nonsense, it’s quite unfair, there’s rules on rules on rules, and if you break one, wham”—she made a slicing gesture across her throat—“out you go, like last year’s garbage. They thought they had snicker-snatched a little girl—fairies love taking little girls, it’s like an addiction with them—and when they found out they had a little boy who just looked like a little girl on the outside, uh-oh, donesies. They threw him right back.”

“Oh,” said Nancy.

“Yeah,” said Kade, emerging from the maze of books. He wasn’t carrying Nancy’s suitcase anymore. Instead, he had a wicker basket filled with fabric in reassuring shades of black and white and gray. “We had a girl here a few years ago who’d spent basically a decade living in a Hammer film. Black and white everything, flowy, lacy, super-Victorian. Seems like your style. I think I’ve guessed your size right, but if not, feel free to come and let me know that you need something bigger or smaller. I didn’t take you for the corsetry type. Was I wrong?”

“What? Um.” Nancy wrenched her gaze away from the basket. “No. Not really. The boning gets uncomfortable after a day or two. We were more, um, Grecian where I was, I guess. Or Pre-Raphaelite.” She was lying, of course: she knew exactly what the styles had been in her Underworld, in those sweet and silent halls. When she’d gone looking for signs that someone else knew where to find a door, combing through Google and chasing links across Wikipedia, she had come across the works of a painter named Waterhouse, and she’d cried from the sheer relief of seeing people wearing clothes that didn’t offend her eyes.

Kade nodded, understanding in his expression. “I manage the clothing swaps and inventory the wardrobes, but I do custom jobs too,” he said. “You’ll have to pay for those, since they’re a lot more work on my part. I take information as well as cash. You could tell me about your door and where you went, and I could make you a few things that might fit you better.”

Nancy’s cheeks reddened. “I’d like that,” she said.

“Cool. Now get out, both of you. We have dinner in a little while, and I want to finish my book.” Kade’s smile was fleeting. “I never did like to leave a story unfinished.”

Excerpted from Every Heart a Doorway © Seanan McGuire, 2016

Find an independent bookstore selling this book: