Glen Keane, animator of Ariel, the Beast, and Aladdin, found himself at a bit of a loss after finishing work on Tarzan. He was assigned to work on Treasure Planet, where he was responsible for the innovative animation used for John Silver, but he was not entirely happy with the project. He felt that Treasure Planet was yet another example of stepping away from what, in his opinion, Disney did best—fairy tales. Keane began putting together ideas for one of the few remaining “major” fairy tales that Disney had not yet animated—Rapunzel.

His plans for a Rapunzel feature ran into just a few small snags.

Spoilery, since this is a film I can’t really discuss without discussing the ending…

First, despite the launch of the very successful Disney Princess franchise, the Disney animation studio had, for the most part, backed away from the fairy tale films to explore other things—dinosaurs, bears, transformed llamas, aliens invading Hawai’i, and things apparently meant to be talking chickens. That most of these films did far worse than the fairy tale features, even before getting adjusted for inflation, did not seem to stop the studio. Second, Keane found himself struggling with the story (he had previously worked primarily as an animator, not a scriptwriter, although he had contributed to story development with Pocahontas and Tarzan) and with technical details, most involving Rapunzel’s hair. After four years of watching this, the studio shut down the project in early 2006.

About three weeks later, the studio opened the project again.

During those weeks, John Lasseter, previously of Pixar, had been installed as the Chief Creative Officer of Disney Animation. Lasseter admired Keane’s work, and if not exactly sold on the initial concept Keane had for the film, agreed that focusing on something Disney was known and (mostly) loved for, fairy tales, was a good idea.

The next decision: how to animate the film. Lasseter, not surprisingly, wanted Tangled to be a computer animated film. Keane originally had a traditional hand drawn film in mind, but a 2003 meeting with computer animators, which focused on the comparative strengths and weaknesses of hand drawn and CGI films, convinced him that computer animation had potential. But Keane wanted something a bit different: a computer animated film that didn’t look like a computer animated film, but looked like a moving, animated painting. Even more specifically, he wanted computer drawings that looked fluid, warm, and almost hand drawn. He wanted CGI films to use at least some of the techniques that traditional animators had used to create realistic movement and more human looking characters.

If at this point, you are reading this and wondering why, exactly, if Keane wanted a film that looked hand drawn, he didn’t just go ahead with a hand drawn film, the main reason is money, and the second reason is that computer animated films had, for the most part, been more successful at the box office than the hand animated films, and the third reason is money. Keane also liked some of the effects that computers could create—a fourth reason—but the fifth reason was, again, money.

Some of the effects Keane wanted had been achieved in Tarzan or over at Pixar; others had to be developed by the studio. Animators studied French paintings and used non-photorealistic rendering (essentially, the direct opposite of what rival Dreamworks was doing with their computer animation) to create the effect of moving paintings.

This still left animators with one major technical problem: animating Rapunzel’s hair. Hair had always been difficult for Disney animators, even when it consisted of one solid mass of color that didn’t necessarily need to move realistically. Watch, for instance, the way Snow White’s hair rarely if ever bounces, or the way most of Ariel’s hair remains a single solid mass. Rapunzel’s hair, however, served as an actual plot point in the film, and therefore had to look realistic, and in one scene even had to float—realistically. It’s quite possible that the many scenes where Rapunzel’s hair gets caught in something, or proves difficult to carry, were at least partly inspired by the technical issues of animating it. Eventually, an updated program called Dynamic Wires solved the problem.

By this point in development, Disney executives realized that Tangled would be a milestone for Disney: its 50th animated feature. Animators added a proud announcement of this achievement to the beginning of the film, along with the image of Steamboat Mickey. They also added various nods to earlier films: Pinocchio, Pumba, and Louis the alligator all just happen to be hanging out in the Snuggly Ducking pub, though Louis is less hanging out, and more condemned to servitude as a puppet, and Pinocchio is hiding. When Flynn and Rapunzel visit the library, they find a number of books telling the stories of previous Disney princesses, and somewhere or other, Mother Gothel managed to find the spinning wheel that proved so disastrous to Princess Aurora. Such touches were hardly new to Disney films, of course—the next time you see Tarzan, pay careful attention to Jane’s tea service—but Tangled has more than the usual number.

(Incidentally, my headcanon is that Mother Gothel, impressed by Maleficent’s admirable skin care program and skill in psychological warfare, picked up the spinning wheel as a memento of her idol, but I have to admit this is not actually supported by anything in the film.)

Tangled also had to contend with other Disney marketing issues—for example, the decision to put Rapunzel into a purple dress. Sure, purple is the color of royalty, but wearing purple also helped distinguish her from blonde Disney princesses Cinderella (blue) and Aurora (pink.) Even more importantly, this also allowed the Disney Princess line to finally offer small children a purple dress, which was apparently felt to be a decided lack. That didn’t completely solve the color problem, since the Disney Princess lineup still doesn’t have any sparkly orange and black dresses—small emo children also want to sparkle, Disney!—but I think we can count it as progress.

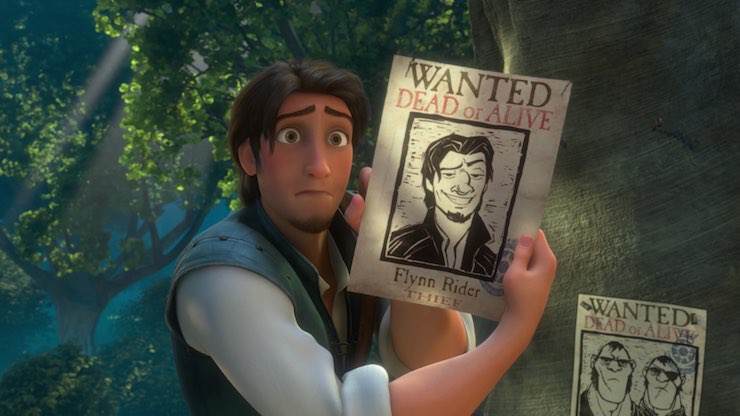

The other major marketing issue had less to do with merchandising, and more to do with the recent release of The Princess and the Frog, a film that, despite its trademark Disney fairy tale status, had proven to be a slight disappointment at the box office. Disney marketing executives believed they knew why: the word “Princess” in the title had scared off little boys, who had flocked to The Lion King and Aladdin, two films without the word “Princess” in the title. Why, exactly, those same little boys had not flocked to The Emperor’s New Groove, Atlantis: The Lost Empire, Treasure Planet, Brother Bear, and Home on the Range, films all notable for not having the word “Princess” in their titles, was a question those marketing executives apparently didn’t ask. Instead, they demanded that the new film drop any reference to “Princess” or even “Rapunzel” in the title, instead changing it to Tangled, a demand that would be repeated with Frozen.

That left animators with one remaining issues: the story. After health issues in 2008 forced Glen Keane to take a less active role in the film development, the new directors took another look at the story treatment, and made some radical changes. Keane had originally planned something somewhat close to the irreverence of Shrek. The new directors backpedaled from that, instead crafting a more traditional Disney animated feature. They did avoid the near-ubiquitous sidekick voiced by a celebrity comedian, although Zachary Levi, cast as the hero, comes somewhat close to fulfilling this role. Otherwise, the film hit all of the other Disney Renaissance beats: amusing sidekicks (not voiced by celebrity comedians), songs, an Evil Villain, a romance marked by a song that could be (and was) released as a hit pop single, and a protagonist desperately wanting something different from life.

Which is not to say that Rapunzel is quite like previous Disney heroines. For one thing—as with all of the more recent Disney animated films—she’s not hoping for romance and marriage, or trying to escape from one. Indeed, as the film eventually reveals, she genuinely believes that she is in the tower for her own protection, an argument most of the other Disney princesses—Aurora and, to a lesser extent, Snow White, excepted—fiercely reject. To be fair, the other Disney princesses are essentially ordinary girls. Rapunzel is not. Her hair is magical, which means, Mother Gothel tells her, that people will want it, and possibly harm her in the process. That “people” here really means “Mother Gothel,” does not make any of this less true: the innocent, naïve Rapunzel really is in danger if she leaves the castle, as events prove, and it is quite possible that others might try to make use of her magic hair. To be less fair, the good fairies and the dwarfs really are trying to protect Aurora and Snow White by hiding them in the forest. Mother Gothel mostly just wants to make sure than no one else can access Rapunzel’s hair.

The other chief difference is the brutal, abusive and terrifying relationship between Mother Gothel and Rapunzel. Mother Gothel may seem, by Disney standards, to be a low key sort of villain—after all, she isn’t trying to take over a kingdom, kill adorable little puppies, or turn an entire castle staff into singing furniture, so one up for her. On the other hand, at least those villains had ambitious goals. Mother Gothel just wants to stay young. I sympathize, but this is exactly what spas were invented for, Mother Gothel! Not to mention, spas usually offer massage services, which can temporarily make you forget the whole aging thing! Spas, Mother Gothel! Much cheaper and healthier than keeping young girls locked up in a tower! Disney even has a few on property!

Instead, Mother Gothel, in between shopping trips and expeditions where she is presumably enjoying her stolen youth, not only keeps Rapunzel from leaving her tower and seeing anything else in the world, or, for that matter, helping anyone else in the film, but also emotionally abuses her. The abuse comes not just from keeping Rapunzel locked up in the tower, with little to do and no one else to talk to, but also telling her, over and over again, how helpless and silly and annoying and above all, ungrateful Rapunzel is. This was not entirely new to Disney films, of course: it’s a center part of Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Cinderella’s stepmother and stepsisters were masters of cruel dialogue. But—and this is key—they did not combine this cruelty with constant assurances that no, no, they were just joking, and their targets need to stop being so sensitive. Mother Gothel does, adding the assurance that no one—no one—will ever love Rapunzel as much as she does, summing everything up with her song “Mother Knows Best.” It’s all the worse for being cloaked in words of love.

Also, apparently Mother Gothel has never bothered to buy Rapunzel any shoes. I mean really.

Nor were previous Disney protagonists quite this isolated. Aurora had three loving guardians plus various forest animals, and Cinderella those adorable mice. Even Quasimodo had the Archdeacon and the ability to watch other people from a distance. Mother Gothel is the only person Rapunzel ever sees or interacts with, other than her little chameleon, Pascal, who can’t talk back. It’s no wonder that Rapunzel becomes so emotionally dependent on the witch, and no wonder she tries not to rebel against any of Mother Gothel’s commands. It’s not just that Rapunzel genuinely loves this woman, who does, after all, bring back special treats for Rapunzel’s birthday, and who has agreed to isolate herself in this tower to keep Rapunzel safe. As far as the girl knows, this is the only person in the world who can and will love and protect her. Of course Rapunzel responds with love and admiration and obedience.

Indeed, the most remarkable thing about Rapunzel is that she has any self-confidence left after all this. Not that she has much, but she at least has enough to head off to fulfill her dream—seeing glowing lanterns float up into the sky. (Really, everyone’s goals in this film are remarkably low key. Except Flynn’s, and he sorta gives his up, so that doesn’t really count.) I credit the magic in her hair for granting her some sense of self-worth.

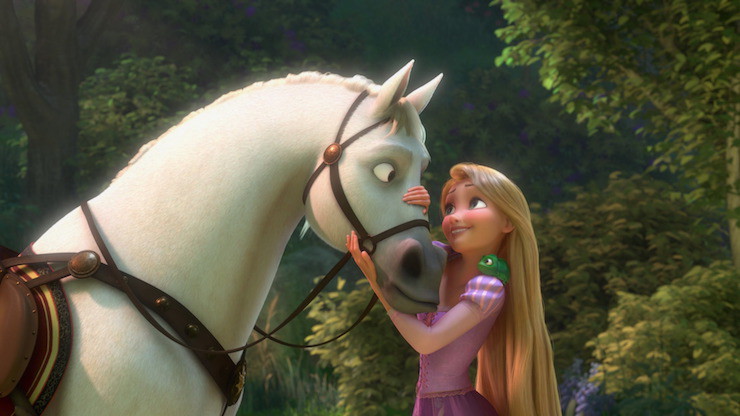

It helps, of course, that almost everyone who meets Rapunzel—including Mother Gothel—almost immediately loves her. True, Mother Gothel seems mostly fond of Rapunzel’s hair, not Rapunzel herself, and more than once finds Rapunzel aggravating, but here and there the film hints that Mother Gothel has a genuine fondness for the girl, to the extent where she can have a genuine fondness for anyone. She does, after all, keep making that chestnut soup for the girl. Meanwhile, the random thugs are so charmed by Rapunzel that they burst out into song, confessing their true dreams. The toughest thug shows her his unicorn collection. Even Maximus the horse, in general deeply unimpressed by humans, is charmed.

The exceptions to this instant love are the minor villains the Stabbington brothers (who barely meet Rapunzel in the film, and are completely won over by her in the cartoon short, Tangled Ever After), and the film’s hero, Flynn, partly because Rapunzel starts off their relationship by clunking him over the head with a frying pan and mostly because Disney was now trying the radical romantic approach of insisting that its hero and heroine hang out for a bit and talk before falling in love. (I know!) Eventually, of course, Flynn—after admitting that his real name is Eugene—falls for her. It’s easy to see why: she’s adorable. It’s a little less easy to see why Rapunzel falls for Eugene, a thief, especially given his initial interactions with her, but he is the person who helped her leave her tower in the first place, and the two have a rather wonderful first date, what with dancing, hair braiding, a visit to the library, stolen cupcakes, and a magical boat ride beneath glowing lanterns.

It’s sweet and cute and even, on that boat ride, beautiful, and far more convincing than many other Disney romances and it’s all lovely until one moment that for me, nearly ruins the film.

I’m speaking of the scene where a dying Eugene cuts off Rapunzel’s hair.

That hair has given Rapunzel some decided challenges. It frequently gets caught on things, and tangled, and—because cutting it destroys the very magical properties that Mother Gothel so desperately wants—it’s never been cut, and seems to be about fifty or seventy feet long. Rapunzel often has to carry it in her arms, and it’s enough of a nuisance that one of her happiest days comes after her hair is carefully and beautifully braided by four small girls (they put flowers in it.) Finally, Rapunzel can join the citizens of the town in a dance. The hair is why she’s spent her entire life in a tower, believing that she’ll be in danger if she leaves. She is terrified that Eugene will freak out when he sees her hair glow with magic and cure the wound in his hand.

But Rapunzel also uses her hair to swing, to climb, to save Eugene and herself, and to hit people. Not by coincidence, the two times that she’s captured also happen to be the two times when she can’t use her hair—when she’s a baby, and when her hair is tied up in a braid. At other times, she’s able to use her hair to keep Eugene and others tied up and helpless. Her hair can heal people. It’s magic. It’s a disability, yes, but it’s a disability that has made her what she is. It’s a disability that she’s turned into a strength.

In a single stroke, Eugene takes that away.

In doing so, Eugene not only removes Rapunzel’s magic (and, may I add, the hopes of various people who could have been cured by her hair) but also goes directly against Rapunzel’s express wishes, refusing to accept her choice to return to Mother Gothel. To be fair, Rapunzel, in her turn, was refusing to accept his choice (to die so that she could remain free), but still, essentially, this is a scene of a man making a choice for a woman, as Eugene makes this decision for Rapunzel, choosing what he thinks is best for her.

And that’s debatable. It’s not that I think that Rapunzel returning to Mother Gothel is a good thing—it isn’t. But as noted, Eugene is dying. Rapunzel wants to save him. As chance happens, just enough magic remains in the cut off hair—conveniently enough—that she can save him. But neither Eugene nor Rapunzel know that this will happen.

And it’s also not clear that cutting off her hair will even free Rapunzel—at least, not immediately. Yes, without the daily dose of Rapunzel’s magic, Mother Gothel will age rapidly and presumably die—presumably. The other side of this is that Mother Gothel is a witch who has already arranged for Rapunzel’s kidnapping—twice—and attacked Flynn and others. At that moment, Eugene has no reason to think that Rapunzel, without her hair—her major weapon—will be particularly safe after his death.

Interestingly, Mother Gothel spends the entire film insisting that she’s doing what’s best for Rapunzel as well.

Granted, the haircut scene happens in part because by that point, Tangled had worked itself into a rather tangled (sorry) plot situation: Rapunzel, watching Flynn bleed out (THANKS MOTHER GOTHEL) promises to stay with Mother Gothel if—and only if—Rapunzel is allowed to heal Flynn. Mother Gothel, no idiot, agrees to this, and since the film has already established that Rapunzel always keeps her promises, and since Rapunzel’s promise did not include any careful wording that would have allowed Rapunzel to go with Mother Gothel and cut off her hair—well, having Rapunzel trot off with a gleefully happy and young Mother Gothel would not have exactly been the happy ending Disney was looking for.

Still, I wish the film had chosen any other way of extricating itself from that mess. Anything that did not involve robbing Rapunzel, who has spent a lifetime locked away in a tower, from making her own choices about what to do with her own hair.

In the film’s defense, Tangled is otherwise a surprisingly realistic take on just how difficult it can be to escape an abusive relationship. In 1950, Cinderella felt absolutely no guilt about escaping a similarly abusive home situation for just one splendid royal ball. In 2010, Rapunzel does—until the powerful moment when she independently works out her true identity, and realizes that Mother Gothel has been lying to her for years. Cinderella, of course, has more people to talk to, and is never under the impression that her stepmother is attempting to protect her. Rapunzel has only a little chameleon, and a few books, and what Mother Gothel keeps telling her—that she is fragile and innocent and unable to take care of herself and will be harmed the moment she leaves the tower. Rapunzel is only able to learn the truth after two days that teach her that yes, she can survive on her own.

As long as she has a frying pan.

I just wish she’d been able to rescue herself at the very end as well.

It’s only fair to note that after all this, Rapunzel kisses Eugene, and marries him. Clearly, she’s less bothered by this than I am.

Otherwise, Tangled has a lot to love: the animation, in particular the boat and lantern sequence, is often glorious; the songs, if not exactly among Disney’s best, are fun—I particularly like the “I’ve Got a Dream” song, where all of the thugs confess their innermost hopes. Tangled also has a large number of delightful non-speaking roles: the animal sidekicks Maximus the horse (who does manage to express himself quite well through his hooves and whinnies) and Pascal, the little chameleon, and several human characters: Rapunzel’s parents, who never speak; one of the two Stabbington brothers, and Ulf, a thug with a love for mime. Ulf’s contributions are all ridiculous, but I laughed.

Tangled did well at the box office, bringing in about $592 million—above any other Disney animated feature since The Lion King. (It was later outdone by Frozen, Big Hero Six and Zootopia.) Rapunzel and her sparkly purple dress were swiftly added to the Disney Princess franchise. If, for some reason, you hate purple, Disney’s official Disney Princess webpage allows you to dress up Rapunzel in a host of different colors, as well as putting her against different backgrounds, and giving her a paint brush. Never say that I never alerted you to pointless time wasters on the internet. Rapunzel and Eugene make regular appearances at all of the Disney theme parks, and are featured in the new Enchanted Storybook Castle in Shanghai Disneyland Park. They also occasionally appear on Disney cruise ships, and an animated series focused on Rapunzel is arriving in 2017.

That, and the booming success of the Disney Princess franchise, was enough to convince Disney executives that they were on the right track.

Time to skip two more films:

Winnie the Pooh was Disney’s second go at animating the Winnie-the-Pooh books by A.A. Milne. A short (63 minutes) film, it proved a major box office disappointment, almost certainly because it was released on the same weekend as Harry Potter and the Deathly Hollows Part Two. The film did, however, have two lasting effects on the studio: it continued the Disney legacy of getting a lot of money out of the Winnie the Pooh franchise, and it found the songwriters who would later be hired for Frozen.

Wreck-It-Ralph, about a video game villain desperately trying to go good, is a Disney original. It did well at the box office, grossing $471.2 million worldwide. At the time of release, it was the third most financially successful film from Walt Disney Animated Studios, after The Lion King and Tangled. (It has since been surpassed by Frozen, Big Hero 6, and Zootopia.) Wreck-It-Ralph was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Animated Picture, and, along with Tangled, was hailed as proof that John Lasseter had, indeed, saved the studio with his arrival. A sequel is supposedly still in the works.

The studio’s biggest success, however, was still to come.

Frozen, coming up next.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.