My first novel has its paperback release in a few weeks, and the hardback release of its sequel comes a couple of weeks after that. It’s an astonishing time, but it’s also humbling: more and more I find myself scanning and rescanning my bookshelves, reading the names of the amazing authors whose words continue to teach me so much about what I do today.

There’s J.R.R. Tolkien, of course, who first exposed me to the glory of a world of imagination steeped in myth.

There’s Robert Jordan, who opened new and enchanting vistas at just the right time in my life.

There’s Anne McCaffrey, who revealed how a writer could pluck emotional strings into a wrenching ballad.

There’s Michael Crichton, who started me thinking about how to incorporate the “real worlds” of science and history into a thriller.

There’s Dan Simmons, who taught me about seamlessly bridging literary and genre sensibilities.

There’s George R.R. Martin, who showed me the bravery of an author in confident command.

There’s Mary Robinette Kowal, who gave me the great gift of saying that maybe I could do this, too.

There’s Neil Gaiman, who is a bloody genius and continues to make sure none of the rest of us can get too cocky about our abilities.

So very many more.

Shelves upon shelves of them. Double- and triple-stacked, God help me.

But among them all, perhaps one author stands out more than any other. He’s the reason I decided my first series would be Historical Fantasy. And he’s the reason I wanted to write this post—not only as a nod to my own past, but also as a suggestion to you all to read the work of someone I see as a bit of a neglected master.

The author is Parke Godwin, and by the time he passed away in 2013 he had written over twenty novels. His range was extraordinary, allowing him to move from a historical love story built around the legend of Saint Patrick (1985’s The Last Rainbow) to a Science Fiction satire of modern religion and economics in the vein of Douglas Adams (1988’s Waiting for the Galactic Bus) to one of the finest historical retellings of Robin Hood I’ve ever read (1991’s Sherwood)—back to back to back.

And all of them are fascinating reads. Of Waiting for the Galactic Bus, Jo Walton (an amazing writer herself) has said, “If you like books that are beautifully written, and funny, and not like anything else, and if you don’t mind blasphemy, you might really enjoy this.”

And Sherwood … well, read this:

Fatter and slower than the rest, Tuck it was who turned to catch his breath, see it all, and tell the wonder afterward. There was the field, deadly as that at Stamford Bridge, Lord Robin bounding high as a hound on the scene over the stubble after the reeve—

“Run, Much! Run for the wood!”

—and the miller, young and strong but nigh run out, trying to push himself faster but losing ground to the sheriff’s men close enough now to stand and take aim on him. The reeve heard Robin shout, reined short, and wheeled his horse about. Robin stopped dead, waving cordially.

“Aye, it’s me, little man. Have a go?”

The Norman hesitated for one fatal moment. Tuck saw it all: crossbolts flying and poor Much jerking as one hit him, going down in the wheat. And the reeve deciding that one Robin was worth two millers, putting spurs to his horse. Robin took his stand, slow or quick, Tuck couldn’t tell for the movement was that smooth, the whole body of the man flowing into the press of his bow—and down out of the saddle went the Norman, pinned neat as a corn doll to a reaper’s stack, and Tuck could hear the cheering from the folk in the field, the men’s sound deep and dust-raw, the higher voices of the women rising over them sweet as a sanctus sung by angels.

Hoch, Robin! A Robin!

My battered copy of the paperback is permanently seamed to this passage. All these years later, I still get goosebumps reading it. And unlike so many authors or books I’ve outgrown, passages like this are undiminished with the passing of time. To the contrary, I read them now with a writer’s eyes and love them all the more.

But it actually wasn’t Sherwood or any of these great books that first drew me to Godwin. It was instead one of his earlier novels, Firelord, which was published in 1980. I read it around 1994, after Avon Books put it out in paperback with a gorgeous cover by Kinuko Craft.

This is the story of King Arthur, told from his own perspective. And, well, let’s just hear it from him:

Damn it, I haven’t time to lie here. Whatever comes, there’s more for a king to do that squat like a mushroom and maunder on eternity.

Dignity be damned, it’s a tedious bore.

Even when he was wounded, Ambrosius told me he hated being carried in a litter like a silly bride. Slow, uncomfortable, and the wounds open up anyway. Mine are rather bad. The surgeons tell me to prepare for their ministrations—Jesus, spare me the professional gravity—and that priest looks so solemn, I think God must have caught him laughing and made him promise never again.

So tired. So many miles from Camlann, where nobody won but the crowd. And some time to spend here at Avalon listening to the monks chant in chapel. No complaint, but one does wish the love of God guaranteed an ear for music. They do not speed the hours.

So, this testament.

Young Brother Coel who writes it for me is very serious about life, but then no one ever told him it was a comedy. He thinks I should begin in a kingly manner at once formal, dignified and stirring. I was never all three at once, but to take a fling at it:

I, Arthur, King of the Britons, overlord of the Dobunni, Demetae, Dumnonii, Silures, Parisi, Brigantes, Coritani, Catuvellauni—

—am disgusted and out of patience, being up to my neck in bandages like a silly Yule pudding. I’d write myself if I had an arm that worked.

Aside from my usual classes on medieval culture, I get to teach creative writing now and again. And I tell you this: I could pull that passage apart for an hour. In that single page—the first page of the novel, in fact—Godwin made a human being more real than Hamlet. I can see King Arthur’s tired smile. I can hear, just over the scratch and pull of Coel’s hand on parchment, the voices echoing through the cloisters to his room. I can smell the sweet incense fighting off the scents of decay. I can feel the life of a wounded man, lain upon his deathbed, telling the story of who he is and what he has been.

And then there’s another page. And another. Each more true and deep than the last. His retelling of re-imagining of the Battle of Camlann is gripping. His account of the affair between Lancelot and Guenevere, told in Arthur’s weary voice, is powerful in ways that grow more true for me with each passing year.

When I read this book, I found myself entranced by a writer whose capabilities were beyond anything I’d read before.

I’d been interested in King Arthur in a passing way before I read Firelord. But after I read this book I was deeply infatuated with the man and his times. I devoured Arthurian fiction and non-fiction. In my earnest naivety I even started writing a screenplay about Arthur that would do more justice to the legend than the silliness of First Knight … a bad movie made far, far worse for me by the fact that I was madly in love with Julia Ormond at the time—could in fact think of no better casting for Queen Guenevere—and then they wasted her character on doe-eyed pining for Richard Gere (!) as Lancelot.

Hell, there’s little question my fascination with Arthur had no small hand in me becoming a medievalist.

By now I have many favorite works of Arthuriana—one of my favorite works in all literature, in fact, is the magnificent Alliterative Morte Arthure, a powerful poem of the late fourteenth century—but nothing ever struck me as being as real as Godwin’s Arthur.

The biggest trick of it all, of course, being the fact that despite all the deep research Godwin had clearly done—and as a medieval scholar I can tell you that it was considerable—Firelord isn’t historical fiction.

It’s historical fantasy.

Godwin gets so much of the history dead-on right, yet his Merlin—while not the time-hopping Merlin of Disney’s Sword in the Stone—still has magic of a kind. His Morgan le Fey is indeed of the Faerie. His Lancelot, a late and very foreign French add-on to the Arthurian myth, is more present in his story than the older Briton hero, Gawain.

None of that fits with whatever “history” King Arthur can be said to have.

But, then, the more one learns about Arthur the more one realizes that he is ever a construct of story. There was a historical man of some sort behind him, of course: he was likely a native Briton leader who earned the epithet “the Bear” (thus, by way of the Latin, Arthur) for his success in holding back the tide of the Anglo-Saxon invasion in the first half of the sixth century. But even in our earliest mentions he is hardly of this world.

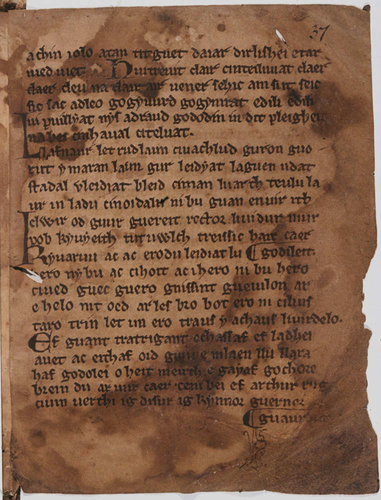

Take, for instance, Y Gododdin, a poetic lament for those who fell at the Battle of Catraeth. In Stanza 99 of this poem, traditionally ascribed to the seventh-century hand of the Welsh poet Aneirin, we hear of the astonishing exploits of a warrior:

Ef guant tratrigant echassaf

ef ladhei auet ac eithaf

oid guiu e mlaen llu llarahaf

godolei o heit meirch e gayaf

gochore brein du ar uur

caer ceni bei ef arthur

rug ciuin uerthi ig disur

ig kynnor guernor guaurdur.[He pierced three hundred of the boldest,

struck down their center and wing.

Worthy before the most noble lord,

he gave from his herd horses in winter,

he glutted black ravens on the wall

of the fortress, though he was no Arthur:

among those powerful in deeds

in the front rank, like a wall, was Gwawrddur.]

Even from our earliest notices, it seems, Arthur already exists in that enchanted gray area between man and myth: a legend of impossible exploits that happened here … back then. Like Aneirin, throughout the Middle Ages and well into our modern age, authors have consistently fit Arthur within the timeline of our historical reality—even as the very facts of his story refuse such a placement.

So a tale of King Arthur is hardly ever historical fiction. Arthur is, instead, almost always historical fantasy.

And I have found no one better at walking this line, at accepting this (non-)reality, than Godwin. As he writes in his acknowledgments of Firelord:

Arthur is as historical as Lincoln or Julius Caesar, merely less documented. Almost certainly he succeeded Ambrosius as overlord of the Britons. Geraint was indeed Prince of Dyfneint, Marcus Conomori was overlord of Cornwall. Trystan appears to have been his son, though I have kept the usual form of the legend. Peredur was actually a prince who ruled at York. Guenevere is probably as historical as the rest; like them, she is remembered with kindness or severity, depending, as Arthur notes, on who is telling the tale.

That they didn’t all live at the same time is beside the point. Very likely some of them did. Assembled on one stage in one drama, they make a magnificent cast. It should have happened this way, it could have, and perhaps it did.

I could hardly agree more. When I first started writing my historical fantasy The Shards of Heaven, I inscribed that last line of his at the top of my outline. It has stuck with me throughout every word of the series. For me, that line is historical fantasy in a nutshell, and if you like the genre at all—which should be the case of whether you like history or fantasy (or both!)—I urge you to pick up something of Parke Godwin, a master of the genre.

Hoch, Godwin! A Godwin!

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Literature at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. The Gates of Hell, the follow-up to The Shards of Heaven, his historical fantasy series set in Ancient Rome, comes out this fall from Tor Books.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Literature at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. The Gates of Hell, the follow-up to The Shards of Heaven, his historical fantasy series set in Ancient Rome, comes out this fall from Tor Books.