Disney executives could not help but notice a few things during the 1990s. One: even accounting for inflation, science fiction films continued to do very well at the box office, if not quite grossing the same amounts as the original Star Wars trilogy. And two, many of the fans who flocked to Disney animated films, theme parks and the newly opened Disney Cruise Line were teenagers. Why not, executives asked, try an animated science fiction or adventure film aimed at teenagers? It would be a bit of a risk—the company’s previous PG animated film, The Black Cauldron, had been a complete flop. But they could bring in directors Kirk Wise and Gary Trousdale, whose Beauty and the Beast had been a spectacular success, and who had also added more mature elements to The Hunchback of Notre Dame. It was worth a try.

In theory.

Wise and Trousdale jumped on the offer. They had no interest in doing another musical, and had some ideas about a potential adventure film. Where exactly those ideas came from is a slight matter of dispute: the directors claimed that the film’s initial major inspiration came from Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth, their own researches into legends of Atlantis and the writings of Edgar Cayce, and Indiana Jones films. A number of critics and fans claimed that the film’s major inspiration came from the Japanese anime Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water, which I have not seen, in another example of Disney lifting from Japanese anime, consciously or not. Wise and Trousdale both strongly disputed the anime claims.

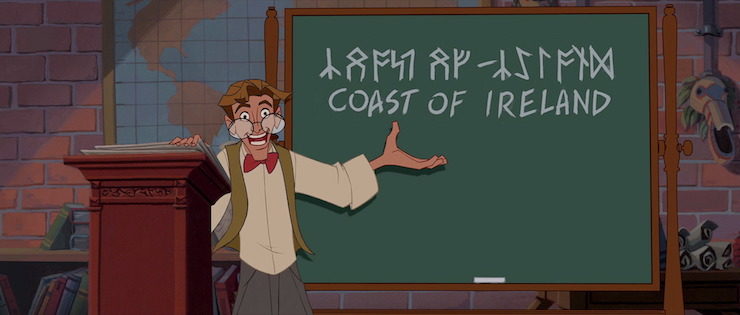

Regardless of the inspiration, the directors and executives agreed on a few elements. One, the new film would absolutely, positively, 100% not have songs, and especially, it would absolutely, positively not have a power ballad. That particular decision did not go over well with the Disney marketing department, now accustomed to—some said fixated on—attaching a potential top 40 hit to each and every hit. As a compromise, one was snuck into the closing credits. The song, “Where the Dream Takes You,” was a total flop, but at least tradition had been maintained. Two, Atlantis would absolutely, positively, not follow the post-Aladdin tradition of adding a celebrity comedian sidekick: this had not worked well for them in Hunchback of Notre Dame. Comedic characters, sure—in the end, the film had about six of them—but not a Robin Williams/Eddie Murphy/Danny DeVito/Rosie O’Donnell type. Three, the new film would have a new language. They hired linguist Marc Okrand, who had helped develop Klingon, to develop Atlantean. Four, the film would be animated in the old fashioned, CinemaScope ratio, as a homage to the old adventure films.

Wise and Trousdale also wanted—and got—ongoing changes to the script, often well after sections were animated, and often to the film’s detriment. Animators, for instance, had almost finished the film’s prologue—an exciting bit of animation featuring the robotic Leviathan killing a group of Vikings, preventing them from reaching Atlantis. Exciting, certainly, but the directors and story supervisors, somewhat belatedly, realized that introducing the Atlanteans as the sort of people who sent killer underwater robots after Viking explorations was perhaps not the best way to make them sympathetic. The prologue was scratched and replaced with a sequence showing the destruction of Atlantis, and introducing Nedakh and Kida as sympathetic survivors of complete cataclysm, trapped on an island sunk far, far beneath the sea.

This was perhaps not the wisest move. On its own, the new prologue, which featured the flying ships and air machines of Atlantis, ended up raising more questions than it answered. For instance, given that the people of Altantis have flying airships, why are they still only using BELLS to alert the population of an incoming tsunami, instead of another mechanical method, especially since we just saw them using radio? Why are they wearing what appears to be Roman clothing? (This is particularly odd, given the film’s later insistence on designing Atlantis to resemble cultures on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and even some Asian cultures, with Mayan art a particular influence. Why not use Mayan inspired clothing?) Why is Kida’s mother stopping mid-flight and kneeling down in the streets to tell her daughter that they don’t have time to let the poor little girl take all of five steps back to get her doll—especially since, as we soon see, the two of them are standing in what ends up being the one safe place in Atlantis? If you have time to tell her this and to get sucked up by high energy beams, surely you have time to rescue a little doll?

Perhaps more importantly, the prologue established that Kida and Nedakh and the other Atlanteans were alive both during the fall of Atlantis and in 1914, the date of the rest of the film—making them four or five thousand years old, give or take a few thousand years. Which raised still more questions: what are the Atlanteans doing about population control, given that they are trapped within a relatively small area with limited resources and a very long lived population? Since at least some of them could remember the surface, did any of them ever try to return to it, and if so, why did they (presumably) fail, given that at least initially, they had access to robot technology? Why—and how—did they forget how to control their flying robot machines? How can Kida later claim that her fellow Atlanteans are content because they just don’t know any better when, well, they clearly do, given that they can all presumably remember, as she can, the days before the destruction of Atlantis?

Also, why are there flying dinosaurs in Atlantis?

Also, given that Kida and Nedakh lived in Atlantis before its fall, why exactly do they need a geeky 20th century American scholar to translate their language for them? Were they—the ruling family—simply never taught how to read?

Which brings me back to the plot of the film, which, after the destruction of Atlantis, focuses on Milo, a hopeful scholar whose real job is to keep the boilers going at the Museum (i.e., the building that would eventually become the Smithsonian Institution, since this film really wants you to know that it knows that the Smithsonian Institution wasn’t called that in 1914). After a sad day of not getting funding (many of you can probably relate), Milo trudges home to find a Mysterious Woman With Great Legs sitting in the darkness. This would be the tipoff for anyone not named Milo to realize that something decidedly hinky was going on: as a seven year old watcher wisely pointed out, “Good people don’t turn off the lights like that.” Milo, however, is so excited to be getting his funding—and an incredible amount of it, enough to cover a small army, submarines, bulldozers, and trucks—he ignores the extreme wrongness of this all and joins the crew as they go off to explore the Atlantic.

(Earth to Milo: most archaeological digs do not require a military escort, and you’ve been working long enough at a museum to know this.)

Said crew includes the usual misfits, most speaking in heavy ethnic accents: the cute Mexican engineer girl, an Italian demolitions expert, a cook who somewhat inexplicably thinks that stuff served only in inaccurate movies about the Wild West is appropriate chow for a sub, the creepy French guy very into dirt, the Mysterious Woman With Great Legs, a stern military officer whose agenda is apparent to everyone but Milo, a nice friendly black doctor who also knows Native American healing, yay, and elderly radio operator Wilhelmina Packard, the hands down standout of the group and the film, more interested in gossiping with her friend Marge than in small details like, say, the imminent destruction of the submarine she’s on.

Off the team of misfits and redshirts go, diving down, down, down into the Atlantic Ocean, where—despite the inevitable bragging that the submarine is indestructible and nobody needs to worry, the submarine turns out to be very destructible indeed and everyone needs to worry. Fortunately enough they end up in a series of caverns hidden well beneath the ocean, conveniently marked out with a nice if somewhat bumpy road. Hijinks ensue, until the team reaches Atlantis and some flying dinosaurs, and things start to go very wrong. Not just for them, but for the film.

By this point, Atlantis has been under the sea for thousands of years, and things aren’t going well: the lights are going out, they can’t remember how to turn on their flying machines, and they can’t fix anything because they can’t read their native language—see above. Fortunately, since Atlantean is a “root language,” they do have an immediate grasp of all contemporary languages, including French, Italian and English, a quick way to handwave any potential communications issues and ensure that subtitles won’t be needed. Those of you about to point out that learning Latin does not exactly lead to fluency in Italian, Spanish, Portuguese or other Romance languages should be warned that this film is not safe viewing for linguists.

It’s at this point where the film pretty much stops making much sense at all if you try to think about it, which I advise not trying. Basically, the dark skinned Atlanteans have forgotten how to use any of their advanced technology, even though the robot Leviathan and various glowing crystals are still working just fine, and it seems highly unlikely that all of the Atlanteans would have forgotten that the crystals are basically keys for the flying vehicles, but moving on. So anyway, the Atlanteans are in a pretty bad shape, and about to get into worse shape now that the military part of the adventuring crew has arrived, prepared to steal the Atlantean power source, without even one person saying, “Uh, given that this power source completely failed to stop the cataclysm that sank Atlantis to the sea, maybe we should try to find some other energy weapon to use in the soon arriving World War I instead.” Or even one person saying, “Huh, so if this power source comes from the energy of the Atlantean people, will it work when all of them are dead? ‘Cause if not, maybe this isn’t the best way to go.”

Of course, since the once-advanced (and dark skinned) Atlanteans are now down to using just spears, and because their badass leader princess has been mostly incapacitated, this means that it’s up to Milo and the motley crew to try to stop the evil general and the Mysterious Woman with Great Legs.

In other words, it turns into a pretty standard White Guy Saving the Ambiguously Racial Culture.

It’s a pity, largely because Kida is introduced as a kickass character who should and would be able to save her people and her civilization all by herself—if only she hadn’t forgotten how to read, leaving her completely dependent on Milo’s translation skills. And if only she wasn’t spending most of the film’s climax trapped in an energy container unable to do anything. So instead of getting to be an action hero, she spends most of the film yelling, getting yelled at, or turned into an energy beam for others to fight over—making her in some ways even more passive than Cinderella and Snow White, who are able to take control of at least part of their destiny through hard work.

The film fails Kida in other ways as well. It’s more than understandable that her main focus is on deciphering her culture’s forgotten writing and restoring their energy system; it’s considerably less understandable for her to be so quickly trusting of the first group of strangers she’s seen in thousands of years, especially given that several of them virtually scream “DON’T TRUST ME” and one is a slimy guy who tries to hit on her within seconds. It’s also considerably less understandable for her—and the other Atlanteans—to take so little interest in, well, everything that’s happened for the last few thousand years outside Atlantis.

Though mostly, this feels less of a failure for Kida, and more like a wasted opportunity: two cultures who have not met for thousands of years, one rapidly advancing through technology, another partly destroyed by advanced technology, and now losing what little they had. It could have been a fascinating clash. Unfortunately, it’s mostly dull.

Arguably, the most frustrating part of this: here and there, Atlantis: The Lost Empire, contains moments and sequences that do hint at something more, something that could have been great. The entire underwater exploration sequence, for instance, is hilarious and occasionally thrilling. Sure, not all of it makes a lot of sense (if the submarine is powered by steam, which last I checked usually requires fire, why hasn’t the submarine burned up all of its oxygen?) and some of the more thrilling parts seem to be directly borrowed from Titanic (specifically, the dash from the boiler room and the realization that the submarine is doomed), and I have no idea how, exactly, all of the trucks and other equipment that appears later in the film managed to get pulled into the escape vehicles and survive, but even with all of these issues, it’s still a pretty good action sequence. None of the secondary characters are well developed, but a number of them are fun to watch, and I’m kinda delighted to see the engineering role filled by a tough talking Hispanic girl who has actual goals. I also kinda found myself feeling that Milo would be better off with Audrey than with a 5000 year old princess who is frequently frustrated by him, but that’s a minor point.

And as said, pretty much everything Wilhelmina Packard does is golden, even if the film never does answer one of its most gripping questions: did that guy ever come back to Marge? Did he?

But the biggest failure of the film is that so much of it, apart from a few sequences here and there, is simply boring. Partly, I think, it’s because even with the revised prologue, Atlantis: The Lost Empire gives us very few reasons to care about any of its characters other than Milo and arguably Wilhelmina. Plenty of people die, but mostly offscreen and unseen. To its credit, the film does include a scene meant to make us care about the various mercenaries who drowned fighting the Leviathan, but it’s a bit difficult, given that most of these guys were barely on screen. Two later deaths, though enough to earn the film’s PG rating, feel equally empty. But mostly, it’s thanks to a film that, however expensive to produce, simply doesn’t seem to have spent time thinking how any of this works, or how any of it should be paced.

Not helping: the animation. In an early scene, Milo taps a fishbowl with a goldfish, and it’s almost impossible, in a Read-Watch project like this one, not to flash back to the goldfish in Pinocchio and sob a little. It’s not just that Cleo the goldfish is more delicately shaded, and rounder, but that the artists in Pinocchio went to huge lengths to have the glass and moving water change what she looks like. Atlantis: The Lost Empire doesn’t. A few scenes here and there—the journey down to Atlantis and the final set piece—do contain some beautiful frames, but for the most part, the animation is at a lesser level than most other Disney films, despite the $100 to $120 million budget and assistance from computers.

Technically, even with that budget, Atlantis: The Lost Empire pulled a profit, earning $186.1 million at the box office—though, after marketing costs were factored in, this may have been a loss. For Disney, it remained a box office disappointment, especially in comparison to two other animated films released the same year: Dreamworks’ Shrek ($484.4 million) and Pixar’s Monsters, Inc. ($577.4 million). The film Disney had hoped would launch a new line of animated science fiction films had just been thoroughly trounced by the competition.

That did not keep Disney from releasing the usual merchandise of toys, clothing, and Disney Trading Pins. Disney also released yet another terrible direct-to-video sequel, Atlantis: Milo’s Return, cobbled together from the first three episodes of a hastily cancelled TV show, and several video games. Art from the film still appears on several of the Disney Cruise Line ships, and Disney continues to sell some fine art products inspired by the film.

And yet, most of the merchandise except for a couple of trading pins soon vanished. Kida became one of only four human princesses in Disney animated films not to join the Disney Princess franchise. (The others are Eilonwy from The Black Cauldron, a film Disney prefers to forget, and Anna and Elsa, who as of this writing are still not Official Disney Princesses, but rather part of a separate Frozen franchise.) In just a few years, the ambitious Atlantis: The Lost Empire was one of Disney’s forgotten films, used largely as an argument for the studio to move away from the work that had built the company in the first place: hand drawn animation.

Not that the studio was quite done with hand drawn animation or science fiction—yet.

Lilo & Stitch, coming up next.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.