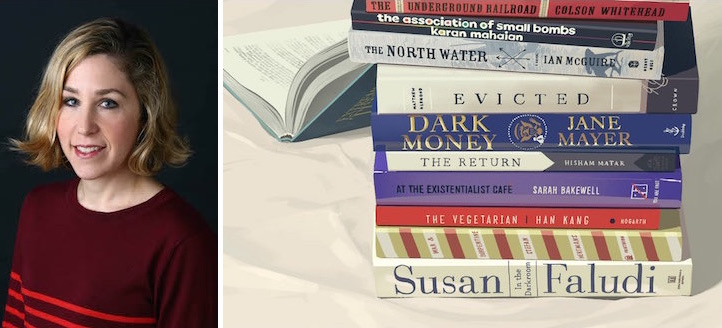

Pamela Paul, editor of The New York Times Book Review, visited Reddit’s r/books yesterday for a short AMA (Ask Me Anything) tied in to the Book Review‘s annual list of The 10 Best Books in 2016. While conversation also touched upon publishing industry trends and how many books Paul has read in a year (76 “for fun” one year long before the internet and her family), most of the focus was on the how and why of the best-of list. How did the editors choose Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, or Han Kang’s The Vegetarian (translated by Deborah Smith)? What ineffable quality determined the difference between the editors’ internal longlist and the final shortlist? Paul gives insight into how the best-of list gets put together, starting in January, and what the selections do (or really don’t) have in common.

Determining the final list is something they think about all year. Even building on previous reviews to narrow things down, they still have to pick just 10 percent of their semi-final list:

The Book Review at The Times reviews about 1% of the books that come out in any given year. Each week, we go through the previous issue and denote certain books as “Editor’s Choices”—these are the 9 books we especially like from that issue. At the end of the year, we pull together all of our Editor’s Choices and narrow them down to 100 Notable Books of the Year—50 fiction and 50 nonfiction. From those, we pick the 10 Best.

But how do books become Editor’s Choices?

[B]asically, the entire year is a winnowing process that culminates in the 10 Best Books. We start thinking about it in January. As we see books that we think are true standouts, we put copies aside so that all editors can read through contenders throughout the year, and weigh in. Books come on and off that list of contenders, and in the course of the year, we check in on it periodically and update it, depending on how people respond to individual titles. Toward the end of the year, around October, the process becomes more intense. I would describe the overall system as democratic, with a decisive wielding of the autocratic sword at the end. Ultimately, hard decisions have to be made, and not every editor at the Book Review will end up with all his or her favorites on the final list, but will hopefully have at least one book he or she lobbied hard for make the final cut.

Paul’s answer to what makes these books so compelling is pithy and a good litmus test for making any sort of favorites lists:

I like to think they have little in common other than a high standard of ambition and excellence. By “Best Books,” we mean books that are extremely well executed in every sense: the scope of the work, originality of thought, writing on a sentence level, storytelling. It’s not necessarily about which books have the most “important” message or a position we agree with. It’s about books we think will stand the test of time, and that people will want to read 5, 10, 20 years from now.

She touched upon the same subject when asked what her personal standouts from the top ten were:

That’s a very hard question to answer. I would say that I personally enjoyed all the fiction. Of the nonfiction books, I’m especially interested in stories that I think need to be told. To my mind, “Dark Money” and “Evicted” are both not only timely and important, but also involved enormous amounts of reporting and genuine sacrifice on the part of their respective authors. I admire their dedication enormously.

As no science fiction or fantasy titles made it onto the list, one Redditor asked if Paul thinks that SFF will ever make it to “must read” status:

I hope they do. I also think a lot of “literary” writers are crossing over more into areas that incorporate fantasy in their work. We recently hired a fantastic columnist for fantasy and science fiction, N.K. Jemison, in order to bring attention to some of the best work in both genres. And this year she won the Hugo! Here’s her most recent column, if you’re interested.

In fact, Don DeLillo’s Zero K was one of the finalists. Paul shared a link to the Book Review podcast, in which one of the editors discusses why Zero K nearly made the cut but didn’t.

Even reading only “about 1% of the books” in a given year, the Book Review crew were able to pinpoint some recurring themes. Paul shares what she saw this year and what themes we might expect to see in publishing in 2017:

We notice all kinds of sweeping trends and then bizarre little microtrends—like a lot of books riffing off Thomas Hardy in the past year, for example. One thing about books is that the literary world moves on a far slower cycle than the news world. So you generally don’t see immediate responses to events in the real world materialize on bookshelves until 9-12 months, or even years later. But obviously, 2017 is going to involve a lot of grappling with the current political moment. There are some quickie books assessing the election and Obama’s presidency coming in early 2017, and I expect a number of deals from people from the Obama administration to be announced. I have to believe that 2017 will bring a serious slowdown if not an end to the coloring book craze, though I have no idea what comes next. Dot to dots??