In honor of the 50th anniversary of both Star Trek and the 1966 Batman TV series, we’ll be spending this final week of 2016 looking at items that relate to one or both of those shows. We start with another William Dozier-produced show about a wealthy man and his acrobatic young sidekick who wear masks and fight crime in a really cool car: The Green Hornet, which is also celebrating its golden anniversary.

The Green Hornet

Created by George W. Trendle

Developed and executive produced by William Dozier

Original air dates: September 9, 1966 – March 24, 1967

Another challenge for the Green Hornet: The Green Hornet was originally created by George W. Trendle, with much of the writing done by Fran Striker, as a radio-show hero in 1936 on WXYZ in Detroit, the same station that debuted The Lone Ranger and Challenge of the Yukon. Britt Reid was intended to be a descendant of John Reid, the true identity of the Lone Ranger (also created by Trendle and Striker).

The show was never as popular as many of the Hornet’s masked counterparts, but he maintained a certain popularity. Trendle had tried to develop a TV show more than once, but it wasn’t until Batman became the hottest thing since sliced bread in early 1966 that it became a reality, as ABC gave the property to William Dozier to develop.

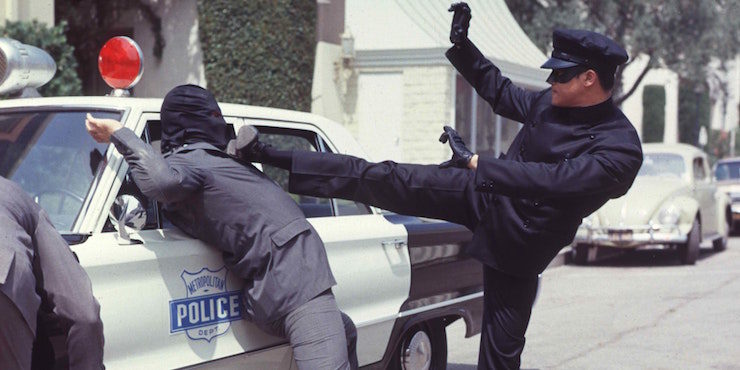

Unfortunately, the Bat-pixie dust had worn off by the time the fall of 1966 rolled around. While Batman‘s first season was a huge success, the novelty had worn off by the second. The darker, more serious tone of Hornet was less appealing to a mass audience, and without Batman‘s pop-art campiness, Hornet proved to be DOA, despite a magnificent reuse of the radio show’s theme music (“The Flight of the Bumblebee”), and it being a star-making turn for a then-unknown young martial artist named Bruce Lee.

Best episode: No single episode stands out as the best, but there are a few particular gems: “The Frog is a Deadly Weapon” makes excellent use of Casey, has a case that actually has some personal stakes for the Hornet, as the bad guy is one of the ones who framed his father, and generally works as a solid actioner.

“Preying Mantis” gives Kato a bit of the spotlight, as he gets an extended fight against Mako’s stunt double. For 1966, it’s a decent portrayal of Chinese culture, which is to say it isn’t entirely a big flaming stereotype. Mako is also one of the few standout villains in the show, most of whom are interchangeable white guys in suits.

The “Beautiful Dreamer” two-parter has another standout villain in Geoffrey Horne’s unctuous spa owner who uses subliminal programming to make normal people commit crimes.

And “Seek, Stalk, and Destroy” is a strong, bittersweet story about military comrades who try to rescue one of their own. What I especially like about this one is that the bad guys are actually pretty good guys. Particular kudos to Paul Carr (best known to Trek fans as Kelso in “Where No Man Has Gone Before“) as the crippled Carter.

Worst episode: The series ended with a spectacular whimper, giving us the truly horrendous “Invasion from Outer Space” two-parter, with Larry D. Mann playing the world’s most unconvincing fake alien. The entire tone of the storyline is an awkward fit with the format for Hornet—it would’ve made a perfectly good Six Million Dollar Man or Wonder Woman episode, but just is head-scratching on this show. And, y’know, it’s awful.

Dishonorable mention for “Freeway to Death.” The team-up of Axford with the Hornet is forced and unconvincing and nowhere near as much as it should be, and Jeffrey Hunter’s steely intensity is wasted on a pretty run-of-the-mill insurance scammer. Also the car chasing on the construction site is stultifyingly dull.

Hornet gun, check. A lot of the Hornet’s enemies in the show are folks who used cutting-edge technology to their benefit, including lasers (which almost sorta kinda worked the way they do in real life, as extreme heat rather than glorified ray-beams), subliminal advertising, a fancy gun that makes no noise or flash, supersonics, a super-computer (though that’s actually a ruse), remote-control arson, scuba divers, a nuclear warhead, etc.

The Hornet himself has several nifty gadgets, such as the hornet sting, the hornet gun, and all the lovely toys in the Black Beauty, most notably the anticipation of drone technology with the flying scanner.

Trivial matters: The Green Hornet has continued to appear regularly in comic books and prose since 1940. Helnit Comics, Harvey, Dell, Gold Key, NOW, and Dynamite have all published Hornet comics, plus DC published a Batman ’66/Green Hornet crossover comic written by Kevin Smith. Prose has been more sporadic, but currently Moonstone has the rights, and they have published three short-story anthologies.

Seth Rogen and Jay Chou starred in a Green Hornet movie released in 2011, written by Rogen and Evan Goldberg and directed by Michael Gondry, which bombed pretty hard. (The script was actually excellent, but Rogen was spectacularly miscast in the lead.) Another Hornet movie is in development.

There was very little crossover in production staff between this show and Batman—of the regular crop of Bat-scripters, only Charles Hoffman and Lorenzo Semple Jr. wrote for Hornet, and they only did one story each, in both cases in collaboration with Ken Pettus (the most prolific writer on the show). Hoffman also wrote the crossover episode of Batman. Several directors helmed episodes of both shows, among them Leslie H. Martinson, Larry Peerce, and george waGGner.

Scenes of the filming of this series were dramatized in the biopic Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story that starred Jason Lee in the title role. Van Williams appeared as the director of the episode, while Forry Smith played Williams playing the Hornet.

In both “The Secret of the Sally Bell” and “Ace in the Hole,” characters are seen to be watching an episode of Batman, which dovetails amusingly with Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson sitting down to watch The Green Hornet in “The Impractical Joker.” The Hornet and Kato made two contradictory appearances on Batman, once as the window cameo in “The Spell of Tut,” and then teaming up (sort of) with the Dynamic Duo against Colonel Gumm in “A Piece of the Action”/”Batman’s Satisfaction.”

The police commissioner is named Dolan, which is also the name of the top cop in The Spirit strip by Will Eisner. This may or may not be a coincidence.

The Batcave Podcast has inspired a spinoff that looks at this show: The Hornet’s Sting. Also hosted by John S. Drew, he’s joined each episode by Jim Beard, the editor of Gotham City 14 Miles.

Let’s roll, Kato. “The Green Hornet is something of a romanticist.” It’s kind of understandable why The Green Hornet never quite caught on. It maintained a lot of the style of Batman—same lettering on the credits, same reliance on spiffy gadgets and a cool car, same basic structure of a rich guy with a sidekick who both dress up and fight crime, William Dozier doing narration—but was much darker both in tone and visuals. It seems like every outdoor shot is in twilight or at night.

Unfortunately, it never quite commits to that darkness. Where Batman embraced colorful villains (both in look and personality), the criminals of The Green Hornet were a tiresome cavalcade of boring white guys who mostly were trying desperately to sound like Edward G. Robinson. And while Van Williams was a charismatic Britt Reid, he was only sporadically successfully menacing when playing the Hornet as a villain.

It’s funny, but we almost never saw the Hornet actually perform any criminal acts, making you wonder why he was wanted in the first place. I mean, we regularly see him muscling in on other criminals’ rackets, and then they betray him, and then they get caught. Amazingly, nobody picked up on this pattern. I also truly wonder what it was the Hornet did to justify being considered the greatest menace in the never-named city. (To be fair, he does break into a bank in “May the Best Man Lose,” and the fake Green Hornet commits murder and other crimes in “Corpse of the Year.”)

Having said that, the show wasn’t without its joys. While the mores of 1966 limited what she could do, Wende Wagner shone beautifully in the role of Casey, and when allowed to stretch her legs (notably in “The Frog is a Deadly Weapon,” where she expertly poses as the dead PI’s secretary, “Invasion from Outer Space Part I” where she doesn’t settle for being a hostage, instead escaping on her own, and to a lesser degree in “Beautiful Dreamer”) did superbly. In general, the show didn’t do too badly by its female characters—besides Casey, there’s Diana Hyland’s high-powered lawyer in “Give ’em Enough Rope,” Signe Hasso’s vicious leopard-controlling bad guy in “Programmed for Death,” Sheilah Wells as a computer operator with a strong reputation in “Crime Wave,” Joanne Dru’s talented managing editor of a rival paper and Celia Kaye’s scheming niece of that paper’s publisher in “Corpse of the Year,” and Linda Gaye Scott’s ultra-cool fake alien with equally fake super-powers in “Invasion from Outer Space.” And Billy May and Al Hirt’s variation on “Flight of the Bumblebee” for the theme song is one of the top ten best TV themes of all time.

Plus, of course, the main reason why anyone remembers this show as anything other than a half-forgotten Batman ’66 footnote: it introduced the United States to Bruce Lee.

It’s impossible to overstate how much of an impact Lee had on American culture, and if you ever doubt it, wander around any city or suburb and count the number of martial arts dojos. That is entirely due to the profound popularity of Lee, who took the U.S. by storm from his starring role on this show in 1966 until his untimely death in 1973. There was an explosion of martial arts films and a similar explosion of the opening of martial arts dojos in the U.S. throughout the 1970s, and it was Lee who really first brought it over here and made it a cool thing for Americans to do.

(That includes me, by the way. I’m a second-degree black belt in Kenshikai Karate, the founder of which was Shuseki Shihan William Oliver, who some have dubbed “the black Bruce Lee.” Oliver was a student of both Kyokushin—which originated in Japan in 1964, and opened a branch in the States right around the time that Lee started appearing in this show—and Seido before forming Kenshikai in 2001.)

Truly the best part of rewatching The Green Hornet is watching Lee in action. Not that that’s always easy: the camera operators had never seen anything like Lee before and the directors were often stymied in trying to shoot the moves of a man who was so fast the film couldn’t adequately capture him. The decision to shoot most of the show in dark light didn’t do Lee any favors, either. Still, watching Lee move is simply riveting. Besides, his role was groundbreaking for Asian actors, and started Lee on the road to improving TV and movie roles for Asian actors across the board.

Hornet-rating: 6

Keith R.A. DeCandido‘s latest release is the Super City Cops novella Avenging Amethyst, from which you can read an excerpt right here on this site. This is the first of three novellas about police in a city filled with costumed heroes and villains published by Bastei Entertainment. Full information, including the cover, promo copy, ordering links, and another excerpt can be found on Keith’s blog. The next two novellas, Undercover Blues and Secret Identities, will be released in January and February.

I managed to catch this series on Syfy a few years back (or was it still called The SciFi Channel at the time?), and I thought it wasn’t bad. It was interesting to see a straighter crimefighting show from Batman‘s producers. I’d often wondered what a serious version of that show would’ve been like, but that wouldn’t have been on the table back then, since Batman comics hadn’t been serious for a decade or two at the time, so it wouldn’t have occurred to anyone. But The Green Hornet had always been played pretty straight on radio and in movie serials, addressing what I gather was a pretty serious organized-crime problem in society at the time. So it was a natural to do the TV version seriously as well. I like how GH is more subdued about using the same tropes as Batman. They have a high-tech car, but it’s not a garish, futuristic concept car; it’s a stealth vehicle that can more or less blend into normal traffic at night (although we never really saw any other traffic in the show, since they couldn’t afford it). And I love it that they had a remote-controlled camera drone nearly 50 years before such things became commonplace in real life.

I realized a while back that when Frank Miller reinvented Batman with Batman: Year One, he either coincidentally or intentionally used the same premise as The Green Hornet: A millionaire hero in a city whose institutions are so corrupt and whose mobs are so powerful that the only way to fight them is as an extralegal vigilante, with the collusion of the one good cop on the force. Although in Miller’s version, I guess the “Kato” was Alfred, not Robin.

As for the show, I agree that Wende Wagner was a standout in the cast, and gorgeous as hell. I love it that Casey was in on the secret, that the female lead got to be a trusted part of the team instead of a perennially clueless love interest. Indeed, it’s rather unusual for the era in that every regular cast member except one (Mike Axford) was in on the hero’s secret. It used to be that the superhero in a TV series typically had no confidantes, or at most one, among the regular cast. Almost everyone being in on the secret is more the sort of thing you’d find in a modern show like Arrow or The Flash.

I really enjoy this series. It is incredibly uneven in places, but I always thought of it as “we’re doing penance for screwing up The Dark Knight by giving you a straight Green Hornet.”

I really looked forward to a big screen movie version, but was so horrified that the producers made it a “campy buddy action comedy” that I left the theater 1/2 way through the picture. My first warning should have been “Staring Seth Rogan.”

I wonder if the writing and execution could have been better if it had been tried as an hour long series.

@2/Alan Balthrop: “I always thought of it as “we’re doing penance for screwing up The Dark Knight by giving you a straight Green Hornet.””

That’s an anachronistic interpretation. The Batman TV series was actually an extremely faithful adaptation of the Batman comics of the ’50s and ’60s; in fact, its silliness was toned down compared to the comics, since Adam West’s Batman never had to deal with Bat-Mite, aliens, magic, time travel, weird transformations and costume variants, and prank wars with Superman like his comics counterpart.

The nickname “Dark Knight” was first applied in 1940, but it didn’t stick, and Batman started to become a lighter character soon thereafter, once Robin was introduced. Certainly he became far lighter in the ’50s and ’60s once the Comics Code Authority was instated and comics became kid-friendly and lightweight. It wasn’t until the late ’60s and early ’70s, in direct reaction to the TV show, that the comics’ Batman started to be written in a more serious and naturalistic way and became “the Darknight Detective.” Apparently it was a Len Wein story in 1980 that revived the long-disused “Dark Knight” nickname, and it was Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One in 1986-7 that really established the image of Batman that fans have today (and as I said, Miller was pretty much grafting the premise of The Green Hornet onto Batman in the process).

So nobody at the time would’ve seen the ’66 series as “screwing up the Dark Knight.” Yes, it was sending up the comics, but it did so by presenting their goofy elements in an exaggeratedly faithful and literal way to play up their kitsch value. And it wouldn’t have occurred to anyone at the time to think that Batman should’ve been more dark and serious, because that perception of the character hadn’t been around for over two decades. Heck, if anything, the show’s Batman and Robin were a lot more serious than their comics counterparts at the time. The Dynamic Duo of the comics had been exchanging witty quips and bad puns with each other on a regular basis since 1940, but the show made them ultra-serious characters whose stiffness the audience was meant to laugh at instead of with, and Robin’s irrepressible wisecracks were reduced to a succession of “Holy blank” exclamations. I suppose comics readers who enjoyed the heroes’ comedic badinage might have felt the show screwed them up, but not in the way that I think you meant.

In short, William Dozier made Batman an absurd and campy adventure-comedy because that was basically what the comics were like in that era. And he made The Green Hornet a straight-up anti-racketeering crime drama with high-tech gadgets because that’s what the radio series and movie serials had been like. Both shows were tonally faithful adaptations of the works they were based on.

Alan: What’s really depressing is that Rogen got the character. Remember, he cowrote the script, and the actual script — removed from Rogen’s rather grating presence — is actually quite good. With an actor of some range — or, at least, range beyond “big doofy stoner” — it could’ve worked. Sadly, Rogen the cowriter and executive producer made the mistake of casting Rogen the actor………

I will amend one thing to what Christopher said: Batman ’66 was faithful to the comics of the previous decade. In 1964, the comics had started moving away from the goofiness under the direction of Julius Schwartz. The comics Dozier was familiar with were reprints of the 1950s stuff that was as Christopher described them.

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

@4/krad: That’s true, but the change was fairly gradual, and the comics that were contemporaneous with the show were still a lot closer to it in tone than the comics of the ’80s and beyond. The Batman of that era’s comics was starting to be seen as more of a straight adventure character, but he was still a much more upbeat and friendly character than the grim loner he became in the ’80s. After all, the famous “The Batman digs this day” panel, where a fully costumed Batman is strolling casually down a crowded street in broad daylight and enjoying the spring weather and the pretty girls, was from 1972. Okay, that was probably from the sillier end of the spectrum of Batman comics at the time, but it was still within the range of his accepted characterization, and of a time when Batman was still seen as a trusted hero rather than a freakish, terrifying vigilante.

As I understand it, a lot of the GREEN HORNET TV episodes were repurposed from original 1940’s radio scripts, which probably explains the “tiresome cavalcade of boring white guys who mostly were trying desperately to sound like Edward G. Robinson.” It also meant that a lot of the crimes and racketeering were rather commonplace or anachronistic–I seem to recall one episode that involved illegally shipping milk from out of state and undercutting local producers, something that was a big deal back then (laws against that weren’t repealed in New York until the 1990’s) but which wasn’t particularly exciting or cutting-edge to 1960’s viewers.

@6/Russell H: I hadn’t known that the show was repurposing radio scripts. That’s interesting. The first season of the George Reeves Adventures of Superman did adaptations of several radio storylines; the premiere episode “Superman on Earth” was an almost verbatim adaptation of the radio script of Superman’s origin story, and other episodes were based on radio stories too, including the infamous “The Stolen Costume” episode, an adaptation of a script from the later half-hour, single-episode version of the radio series which was itself a condensed remake of a longer serial storyline from the earlier form of the radio series. I think they did that story maybe four times in all, including the final TV version.

Russell H: That would also explain why there was a story about illegal alcohol, which really stopped being a major thing after Prohibition was repealed…..

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

I never saw a single episode of this show, so I appreciate the recap, Krad.

The radio show suffers from the same problem as (apparently) the TV show, in that every mobster who associates with the Hornet is eventually taken down by the cops, and yet neither the cops nor the crooks figures it out.

@10/StrongDreams: Well, part of the idea there is that rival gangsters would be fighting each other, turning on each other, and betraying each other all the time anyway. So when every racketeer the Green Hornet either allies with or crosses stingers with ends up defeated or arrested while the Hornet gets away, it just looks like he’s a gangster who’s really, really good at outcompeting his rivals, and who’s clever enough to arrange events so that the authorities do a lot of his dirty work for him. And other racketeers he pursued alliances with would expect him to betray them anyway, just as they would naturally plan to double-cross him as soon as it became convenient. They just hope that they can double-cross him first and outsmart or outshoot him when the time comes. After all, there is no honor among thieves.

Although that still doesn’t explain why he’s considered a master criminal in the first place if he never actually does any harm except to other criminals…

I bought the Kill Bill vol 1 soundtrack album because it included the full length Green Hornet TV theme.