In honor of the 50th anniversary of both Star Trek and the 1966 Batman TV series, we’ll be spending this final week of 2016 looking at items that relate to one or both of those shows. We continue with two shorts that William Dozier made. The first was made between the second and third seasons to convince ABC to add Yvonne Craig’s Batgirl to the show’s opening credits. The second was a five-minute promo Dozier put together to pitch a Wonder Woman TV show.

“Batgirl”

Unaired promo short

The Bat-signal: Barbara fetches a book on butterflies for Bruce, who doesn’t recognize her at first, until she explains that she’s Gordon’s daughter. He and Dick are there chatting with another millionaire, Roger Montrose, the lepidopterist (the book she fetched for Bruce is to settle a bet).

Killer Moth and three of his henchmen are also in the library with designs on kidnapping Montrose. Bruce and Dick sneak off to change clothes to stop the villain, while Barbara’s colleague locks up so no one will come in after closing, though there are still patrons present in Montrose and Killer Moth.

Killer Moth’s goons grab Montrose, while Barbara is thrown into the library lounge and locked in—but she’s got a secret closet in the library (really?) and she changes into her Batgirl outfit (which is on under her civilian clothes, her skirt transforming into her cape).

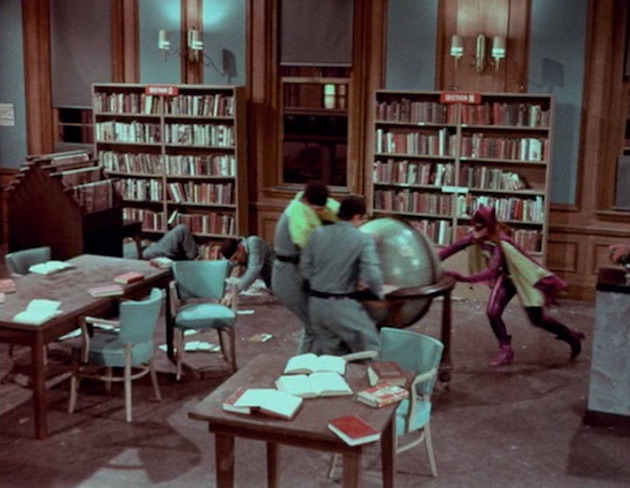

Batman and Robin show up to foil the kidnapping, and fisticuffs ensue. However, Killer Moth uses his spray gun to put the Dynamic Duo in a cocoon, trapping them.

Batgirl bursts in through the window and more fisticuffs ensue. She frees Batman and Robin, at which point more fisticuffs ensue, with Killer Moth and his gang stopped. Once the fight’s over, Batgirl disappears without the Dynamic Duo noticing, leaving them to wonder who she is and where she comes from.

Fetch the Bat-shark-repellant! Batman and Robin get into the closed library using the bat-lock-breaking array. Batgirl has a compact that is equipped with a laser beam.

Holy #@!%$, Batman! When Batgirl bursts into the library, Robin cries out, “Holy apparition!” When she whips out her laser beam compact, Robin utters, “Holy vanity case!”

Meanwhile, the narrator cries out “Holy transformation!” as Barbara is changing into Batgirl.

Gotham City’s finest. We only see Gordon briefly, complaining that he never gets to have dinner with his daughter.

Special Guest Villain. Tim Herbert is completely unmemorable as Killer Moth, a villain never seen on the main TV series, though he was also the villain in Batgirl’s first comics appearance in Detective Comics #359.

Na-na na-na na-na na-na na.

“A new member of our team, or a crime-fighting rival?”

–Batman speculating as to who the new chick in purple is.

Trivial matters: This episode was discussed on The Batcave Podcast episode 48 by host John S. Drew with special guest chum, author, podcaster, and audio drama producer Jay Smith.

This short was produced for the network and never aired, though it is part of the DVD set.

While there was a previous Bat-Girl in the comics, she was Batwoman’s sidekick, Betty Kane, the niece of Kathy “Batwoman” Kane. Those characters were created in response to Fredric Wertham’s accusations of homoerotic subtext between Batman and Robin in Seduction of the Innocent, but were abandoned in 1964 as being too silly. However, William Dozier and Howie Horwitz approached DC about creating a new Batgirl who was Gordon’s daughter, and Batgirl’s costume on the TV show was inspired by Carmine Infantino’s rendering of the character in Detective Comics #359.

Batgirl’s costume is a different shade of purple, and her secret door is in the library instead of her apartment, which was probably done for budgetary reasons, since this entire short takes place on one set, that of the library.

Pow! Biff! Zowie! “You insidious insect!” Mostly I watched this short thinking that Barbara is a terrible librarian, because she allows the place to get totally trashed, which will seriously mess with the physical plant budget for the next year. It’s going to be a nightmare for her as librarian dealing with the bean counters, not to mention all the books that have to be replaced after the fight…

More seriously, though, this is a charming little piece that nicely introduces both Barbara and Batgirl. It doesn’t actually fit with the continuity of the show, nor was it meant to, but it’s a fun little artifact, and you can see why everyone was high on including this new character, as Yvonne Craig’s enthusiasm and skill are on full display. I’m not so thrilled with the bit where she sits provocatively on the desk while Batman and Robin finish the fisticuffs, but that wasn’t the start of a trend, so whatever.

Bat-rating: 5

“Wonder Woman”

Unaired promo short

No real need to break this one down as aggressively, as it’s got even less of a plot than the Batgirl piece. In 1967, with Batman and The Green Hornet both on the air (and neither one cancelled yet), William Dozier pitched a Wonder Woman series to ABC.

Dozier’s Wonder Woman is a goofy, klutzy young woman who can’t even read the newspaper without falling off the couch. Her mother wants her to find a husband and settle down and have a family. She cites a neighbor, Lucille Maxwell, who is twenty-four and already has three kids. (WW’s protest that Lucille isn’t actually married falls on deaf ears. This stands out as the only actual funny line in the entire short.)

Once she changes into costume, she finds herself captivated by her reflection in the mirror—played by a different actor, who is more conventionally pretty—while Dozier narrates her abilities. She knows she has the strength of Hercules, etc., etc., but she only thinks she has the beauty of Aphrodite. (Har har.)

Once she tears herself away from her imagined reflection (which takes a while), she flies out the window, her mother calling after her to stop by Kansas City and say hi to her uncle.

If you ever believe that there is no justice in this world, think on this: nobody made a TV series based on this promo. Which proves that there are smart, intelligent people even in Hollywood. Because there is absolutely nothing redeeming about this concept whatsoever. Reimagining Wonder Woman as a barely competent hero with a nagging mother is an idea that is bone-stupid on every possible level. It’s hard to believe that the William Dozier who gave us Batgirl, Catwoman, Marsha Queen of Diamonds, and Zelda the Great, not to mention Casey and several other strong female characters on The Green Hornet, would stoop to this pair of horrendous stereotypes.

A few years later, one of the better members of Dozier’s stable of bat-writers, Stanley Ralph Ross, would develop a Wonder Woman series starring Lynda Carter which would capture the character much better…

BatWonder-rating: 0

The regular “Star Trek The Original Series Rewatch” and “Holy Rewatch Batman!” will re-commence the first week in January 2017.

Keith R.A. DeCandido‘s latest release is the Super City Cops novella Avenging Amethyst, from which you can read an excerpt right here on this site. This is the first of three novellas about police in a city filled with costumed heroes and villains published by Bastei Entertainment. Full information, including the cover, promo copy, ordering links, and another excerpt can be found on Keith’s blog. The next two novellas, Undercover Blues and Secret Identities, will be released in January and February.

Shorts? But only Wonder Woman wears shorts of the two? :)

Also, check out this Leia-haired Barbara:

I think it’s neat that the pilot presentation shows Batgirl’s costume change working in the same way it did in her comics debut, with the skirt reversing into the cape and a hat folding out into the cowl. I wish they’d kept that for the show. I also hadn’t realized that Killer Moth was the villain in both debuts — although going with Penguin in the final episode was no doubt a better choice.

As for the costume, I’ve said before that Batgirl’s TV costume is actually closer to Catwoman’s comics costume (purple catsuit/cowl and yellow cape vs. purple dress/cowl and green cape) and vice-versa (black catsuit and gold belt and medallion vs. black catsuit and gold belt and Bat-emblem).

As for the Wonder Woman pilot, its actual full title was Wonder Woman: Who’s Afraid of Diana Prince? It was written by Stan Hart & Larry Siegel, and it starred Ellie Wood Walker as Diana, Maude Prickett as her mother, and Linda Harrison as the fantasy Wonder Woman. Harrison had made her screen debut the previous year in Batman: “The Joker Goes to School”/”He Meets His Match, the Grisly Ghoul,” and would go on to play Nova in the first two Planet of the Apes movies.

I’m surprised by this one; my impression had been that Diana only imagined herself to be a superhero at all, though I didn’t see how that could possibly work as a series. Turns out her superpowers are real, but she’s only deluded about her looks, which is profoundly sexist. Also, Ellie Wood Walker isn’t that unattractive to begin with.

Still, I agree it’s a strange way to go with this. Batman worked by playing its premise exaggeratedly straight and letting its silly aspects speak for themselves. Granted, the Wonder Woman comics of the era had been in the doldrums for a very long time; once William Moulton Marston had left, the comics had been written by Robert Kanigher, who was dreadfully sexist and wrote Wonder Woman as being just as utterly preoccupied with romance as every other female character he wrote, as well as doing a whole bunch of imaginary stories about Wonder Woman interacting with her past selves Wonder Girl and Wonder Tot (leading to confusion when another writer thought Wonder Girl was a distinct character and used her in Teen Titans, and it only gets more complicated from there). But still, Kanigher’s Wonder Woman was unquestionably considered a great beauty, and Steve Trevor was hopelessly in love with her. So Dozier’s approach here was far more revisionist than his approach with either Batman or The Green Hornet. I do wonder what he was thinking.

Wonder Woman rewatch? Make it so!!!

I will say this for the Wonder Woman pilot, I wouldn’t mind more superheroes whose parents treat their powers as normal and remind them to stop by and say hi to their out-of-town relatives when they’re flying over the globe (although the rest of it sounds dreadful).

As for Barbara having a secret room in the library, a good librarian is always prepared!

Christopher: Yeah, the first time I saw this, it was a copy-of-a-copy on VHS, and I took Dozier’s word for it that Diana was really plain looking because the picture quality was for shit, so I assumed she was unattractive. Watching it now for this one on a much better print, it’s obvious that the premise doesn’t hold up at all.

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

@4/Ellynne: The premise of Who’s Afraid of Diana Prince? reminds me of another 1967 sitcom attempting to capitalize on the Batman craze — Buck Henry’s Captain Nice, starring William Daniels as a klutzy, mild-mannered police lab tech who invented a super-serum and who was basically pushed by his domineering mother (Alice Ghostley) into a superhero career. That show premiered in January 1967, so it probably predated the WW presentation.

Oh, by the way, Wikipedia says that Stanley Ralph Ross (developer of the Lynda Carter WW series) did an uncredited rewrite on Hart & Siegel’s script because it was deemed unsuitable. If this was the better version, I can hardly imagine what the first draft was like. Oh, and apparently Hart & Siegel were writers for MAD Magazine at the time. It does have sort of a MAD-parody flavor to it.

Ahhh, much appreciated, Keith – even if these two shorts are so thin on content that even doubled-up they’re barely worth a full post.

Batgirl’s first mask looks pretty weird, though I actually prefer the frill-less cycle they gave her in this short.

And while I wouldn’t say no to a Wonder Woman ’77 recap series, I fear even your endless patience would run out somewhere in the middle of Season 2. While it has its own undeniable charm, most of the time it was just tedious, and the average episode would have maybe 5 minutes of the star attraction in the midst of 45 minutes of humdrum spy/cop fiction.

@7/rubberlotus: Yeah… The first season of Wonder Woman on ABC was an impressively faithful adaptation of the ’40s comics, but the two “modern-day” seasons on CBS were a pretty lame attempt to turn Wonder Woman into a Bionic Woman clone. When Bruce Lansbury took over as producer about 8 episodes into season 2, he marginalized Steve Trevor by making him Diana’s boss instead of her field partner, and he pretty much ignored the series’ prior continuity (with episodes implying that Diana had been an IADC agent for years instead of mere months, and a total abandonment of anything to do with the Amazons). Plus, Diana lost her sweetness and warmth from season 1 and became perennially sarcastic and irritable, which was much less appealing. Oh, and she stopped wearing glasses for the most part, making it ridiculous that people couldn’t tell she was Wonder Woman.

“but she’s got a secret closet in the library (really?)”

Strangely enough, the newspaper Batman strip of the era has Barbara/Batgirl operating out of the library, rather than her apartment! I haven’t read all the dailies of that time, but I am guessing that the building was older and had “secret” entrances, sections, etc., which seems more likely than a modern apartment building.

“Those characters were created in response to Fredric Wertham’s accusations of homoerotic subtext between Batman and Robin in Seduction of the Innocent, but were abandoned in 1964 as being too silly. ” I’ve read that in a number of places, but have never seen any proof of the link. It seems odd to attribute designing a female counterpart to a “response to Wertham”, in that many, if not all, male heroes had a female counterpart at some point. The era Batwoman appeared in also had a Bat-Mite and a Bat-Hound, which were more likely an attempt at increasing sales than anything else, and Bat-Girl (Betty) arrived somewhat later, seemingly because her aunt had proved popular. The two female additions were wildly intent upon snagging the guys, but that was what that time period was like. If anything the fact that Bruce & Dick mostly kept them at arm’s length would tend to reinforce Wertham’s allegations! It seems that those who are seeing the creation of the Batwomen as a response to allegations of homsexuality are looking at the era through a modern lens.

kenn: Part of why the time period was like that was because of the devastating effect the Comics Code Authority had on the comics of the time, which was a direct result of Wertham’s book and the Kefauver hearings on juvenile delinquency. Wertham’s thesis was that Bruce and Dick spent all their time together both in and out of costume, so of course they’re ICK! HOMOSEXUALS! GAY COOTIES! GET THEM OFF! and adding a larger supporting cast that included a woman and a dog and a whatever-it-was-Bat-Mite-was made it more like a proper large family than a couple of men shagging.

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

@10/krad: While Wertham’s oppressive influence was certainly real, I think it’s a bit cynical to say it’s the only reason for the “family”-building that comics of the era did. The Batman family was probably inspired by the growth of the Superman family when Otto Binder was writing that series, and Chris Sims of ComicsAlliance has argued that Binder was basically recapitulating what he’d done earlier with Captain Marvel and the Marvel family for Fawcett. And the Marvel family predated Wertham and the Code by a decade or more.

The way Wikipedia puts it is, “Since the family formula had proven very successful for the Superman franchise, editor Jack Schiff suggested to Batman creator, Bob Kane, that he create one for the Batman. A female was chosen first, to offset the charges made by Fredric Wertham that Batman and the original Robin, Dick Grayson, were homosexual.” So according to that, the homophobia did influence how the Batman family was developed, but the primary reason why it was developed was simply to emulate the success of the Superman family.

From what I can piece together, the more direct influence of Wertham was the removal of the Catwoman from the Bat books, for she was the “wrong kind of woman” for the good guys to get caught up with, and was not always made to “pay for her crimes”, which left a female-shaped hole that the creative types attempted to fill with Lois Lane-clone Vicki Vale and/or Batwoman, who was better received. The Wikipedia entry cites a 2004 book as the source of the assumption of Wertham accusations as to why a female Bat was created first, and THAT source may cite evidence from the 1950s, but I’ve never seen any. I just doubt very much that homosexuality was given as much consideration at that time as it is now. Most things make more sense if you follow the money motive, which is constant throughout time.

“and adding a larger supporting cast that included a woman and a dog and a whatever-it-was-Bat-Mite-was made it more like a proper large family than a couple of men shagging”, BTW, is actually a remnant from that period that still stings, as it equates homosexuality with pedophelia, Bruce & Dick not being a couple of men at all. Wertham was a twisted person.

Only today did I realize that the story we’ve been told about the creation of the TV Batgirl doesn’t appear to make sense. Supposedly, Dozier wanted to introduce a female crimefighter to the series in order to convince ABC not to cancel the show despite its sagging ratings. So he went to Julius Schwartz and/or Carmine Infantino at DC Comics and persuaded them to create a Barbara Gordon Batgirl in the books, to pave the way for the character’s introduction on TV.

Yet the first appearance of the Barbara Gordon Batgirl was in the January 1967 issue of Detective Comics, which hit the stands in November 1966. That means the conversation between Dozier and Schwartz/Infantino could have taken place no later than fall 1966- – at which point the show’s ratings decline was not yet precipitous or sustained enough for cancellation to be on the table.

My guess: DC actually created the character entirely on their own and without any interaction with Dozier. When the ratings started to slip and ABC started making noises about canceling the series, Dozier turned to the comics that were already being published for the idea of livening up the show with a female counterpart to Batman. And somehow over the years, the erroneous idea emerged that Dozier had been in the driver’s seat all along.

Opinions?

@13/Steve: You’re reading something in the story that isn’t there. The standard account is that the creation of Batgirl was a response to declining second-season ratings, not to an imminent threat of cancellation. Those are two different things. The first season was a top-10 show in the ratings on both nights, but the second didn’t even crack the top 30. So it was evident quite early in season 2 that the show’s popularity had taken a serious hit. Developing the idea of Batgirl was thus a pre-emptive measure to try to reverse the ratings decline in general — presumably before things got bad enough for cancellation to be considered. At least one source claims that the idea was to boost the show’s ratings with female viewers.

@14/Christopher: Thanks for the link. Very interesting! If Schwartz says that’s what happened, I guess we can believe him. It’s just still seems like an awfully tight turnaround between the initial ratings for season 2 coming in and the issue hitting the stands. Especially when you consider the lead time comics required back then. Also, why did it then take so long for in the character to appear on TV? If they had identified the need for her as early as fall 66 and the ratings were already dropping so precipitously, why not introduce her during season 2 instead of waiting almost another year? Not to mention how weird it is that producers who were so frequently and openly disdainful of the source material would consider it imperative to introduce such a character in the books first. They certainly didn’t seem to feel that way about any of the villains they created for the series. Then again, they did have DC bring back Alfred for a similar purpose.

@15/Steve: On the other hand, Batman ’66 was practically the first live-action comic-book adaptation (other than Atom Man vs. Superman) to use any existing villains from the comics at all. It’s standard operating procedure now, but it was all but unprecedented at the time. Nearly all of the first season’s villains were based on characters from the comics, including some older comics that had been reprinted around the time the producers were doing their research — which is how we got obscure characters like False-Face, Eivol Ekdal, and Mr. Freeze (based on a one-shot villain called Mr. Zero). So by the standards of the time, they were actually pretty dialed in to the comics. I think the reason they went for so many original villains in season 2 is because by then, it had become fashionable among celebrities to want to make guest appearances, so they started writing the villains around the celebs. But that was for the sake of one-shot or at best recurring guest roles. Introducing a new series regular, a hero rather than a villain, was a different matter. It made sense that they’d want the comics to reflect — and promote in advance — a character who would be a regular part of their show. (The only regular character created for the show was Chief O’Hara, although he did make a comics appearance sometime later — which is why IMDb mistakenly credits his creation to Edmond Hamilton, the writer of the issue that first added the TV character to the comics.)

As for why they waited until season 3, it typically takes up to 3 months to get an hourlong TV episode (which is what Batman 2-parters were from a production standpoint) from initial concept to airdate. The second season finale aired on March 30, 1967, only 5 months after Batgirl’s debut issue hit the stands. And it would’ve taken time to develop the TV version of the character, figure out how the show would be reworked to include her, go through a thorough casting process to find the best possible actress (which they absolutely did), etc. It would take longer than just writing a one-shot guest appearance. Note that Commissioner Gordon did first mention his daughter in the King Tut 2-parter that aired in early March, so they were planting the seeds for her debut.

@12/ kenn

He gets a bad rap these days because he’s better-known for his war on comics than he is for his efforts to improve access to mental health for minorities, his work for the New York courts system to make psychiatric treatment available for inmates, and his work with juvenile delinquents (which is how he got into the comics thing in the first place). To be clear, a lot of his ideas about psychology were wrong–he was a disciple of Sigmund Freud, who he corresponded with as a student and who apparently influenced Wertham to become a psychiatrist. He also committed data fraud, rendering his (already dubious, uncontrolled, entirely anecdotal) “study” of connections between comic books and delinquency (even more) worthless.

But he was, perhaps surprisingly considering what his name is most associated with these days, a progressive reformer who did a great deal to try to make mental health treatment available for people who would never had access to it (it’s worth pointing out that in the 1950s heyday of the American fad for psychoanalysis, a New York City psychiatrist with direct ties to Freud could have easily made a fortune treating the well-to-do, instead of focusing his career on opening a low-cost clinic in Harlem and testifying in court proceedings on behalf of inmates and children).

One of the most surprising things when one goes back and reads Seduction of the Innocent is that for all the crap that everyone remembers–the nonsense about Batman and Robin’s love life, the not-quite-as-nonsense about Wonder Woman’s sexuality, etc.–the book also contains a surprisingly modern-sounding critique of advertising, especially ads aimed at children, and a surprisingly modern-sounding critique of body shaming (Wertham was especially appalled at advertisements for beauty and body-shaping products, arguing that comic book ads intentionally tried to instill kids with anxieties about their weight, body shape, muscular development, and complexions in order to sell them useless crap–thereby psychologically damaging them).

And it’s also worth pointing out that many of Wertham’s criticisms of comic books actually were valid, aside from their hypothetical effects on the reader: he called out comics of the era for being racist, misogynistic, and gratuitously violent, and many of them were.

I also feel like I should say that while I think Wertham’s conclusions about some of the effects of reading comics were questionable if not utterly wrong, I think one of the problems with Wertham and his contemporary critics alike is that you can’t have it both ways: defenders of comics at the time were quick to claim that their products were meaningless, disposable, ephemeral products with no lasting effect on the consumer, while Wertham was quick to claim comics weren’t and couldn’t be art while having a permanent effect on the reader’s psyche. The problem, of course, is that if those defenders of comics were right, then it’s hard to justify treating them as art; on the other hand, if Wertham was right about comics having lasting effects, it’s hard not to think that one of the qualities art has is that it impacts and changes the audience in some lasting way, and that a positive effect is as possible as a negative. Thinking, as I do, that comics are art, I do have to consider the possibility that they might have some profound effect–good or bad–on a reader; and yet art seems to me, personally, to be entitled to some of the highest protections a free society can offer without censorship of content, while crap (obscenity, e.g.) may not be; in short, both Wertham and his contemporary critics undermined their own positions.

Anyway. Wertham was an ass, but he was an ass with some laudable points. That was what I mostly wanted to say.