In this monthly series reviewing classic science fiction books, Alan Brown will look at the front lines and frontiers of science fiction; books about soldiers and spacers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

The early 20th Century was a time of marvels—and a time when mass production was putting those marvels in every home. When people think of assembly lines, they often think of Henry Ford and automobiles. But in the same era, a man named Edward Stratemeyer developed a formula for mass producing books for the juvenile market, and in doing so, revolutionized an industry. There were books for boys and girls; books filled with mystery, adventure, sports, humor, science, and science fiction: anything an inquisitive child would want, in a package that encouraged them to come back for more.

When I was eight years old, school was out for the summer, and I’d begun feeling like I had outgrown all of my books. You can only read Doctor Seuss stories so many times before you tire of them. So I went into the basement, where my father had saved pretty much every book and magazine he had ever read, and, like an archaeologist, I searched through every layer of his reading history. Back through Analog, then Astounding and Galaxy magazines. Back through cowboy and mystery novels. Back through Ace doubles and all sorts of paperbacks. Back past paperbacks into hardback books. And finally, on the bottom shelf in an old bookcase, I found the books he had grown up with. There were Bobbsey Twin books, Don Sturdy adventure books, and many Tom Swift books. Two in particular caught my eye: these books were both part of something called the “Great Marvel Series,” and promised adventures of the most sensational variety. The first one, Lost on the Moon, I lost somewhere over the years. The second, On a Torn-Away World, I still own. My father used notes to keep track of which magazine story and book he had read, and when he had read them. And in this case, he had recorded my reading activity—a tiny note in his neat hand penciled on the flyleaf confirms my recollection of when I read it, “ALAN 1963.”

The Plot

I opened the book for this review with great anticipation, barely remembering anything about it. On a Torn-Away World describes the adventures of Jack Darrow and Mark Sampson, two orphans adopted by the kindly old scientist Professor Henderson, who are proud to have just finished (apparently by themselves) their own airship, the Snowbird. After a rather shaky test flight, and before the new paint is fully dry, their guardian decides that this vehicle is suitable for an adventure, flying from the professor’s laboratory in Maine to the wilds of Alaska. They will be searching for medicinal herbs that one the professor’s old friends thinks will revolutionize health care. Accompanying them on their journey will be Washington White, the professor’s black servant, his beloved pet rooster, and Andy Sudds, an older hunter and outdoorsman.

I opened the book for this review with great anticipation, barely remembering anything about it. On a Torn-Away World describes the adventures of Jack Darrow and Mark Sampson, two orphans adopted by the kindly old scientist Professor Henderson, who are proud to have just finished (apparently by themselves) their own airship, the Snowbird. After a rather shaky test flight, and before the new paint is fully dry, their guardian decides that this vehicle is suitable for an adventure, flying from the professor’s laboratory in Maine to the wilds of Alaska. They will be searching for medicinal herbs that one the professor’s old friends thinks will revolutionize health care. Accompanying them on their journey will be Washington White, the professor’s black servant, his beloved pet rooster, and Andy Sudds, an older hunter and outdoorsman.

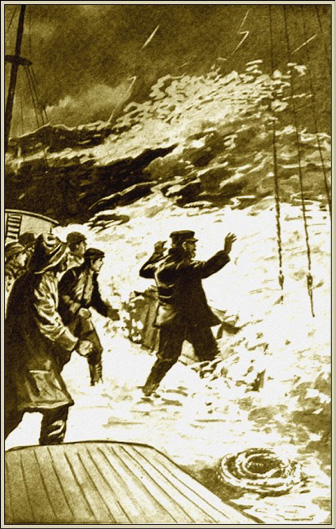

The team pack up their gear, head out, and immediately run into a new Treasury Department airship, charged with protecting the borders of the country from the new threat of air pirates. They then encounter one of these air pirates, who they anticlimactically outrun and lose in the clouds…but those clouds are part of a nasty storm that nearly brings the Snowbird down. Luckily, they catch favorable tail winds and find their way to a town in Alaska, but as they land they are fired upon by natives. After arriving, they meet Phineas Roebach, an oil company explorer, but suddenly there’s a massive earthquake and volcanic eruptions, and a test oil well goes wild. Afterward, the boys and their party find that the force of gravity has diminished, and they are able to make mighty leaps, while a huge globe hangs in the sky, which they think might be a new heavenly body. Professor Henderson uses his telescope to make a shocking discovery, however: the “new planet” is the Earth, so they must be on a fragment of the planet that was launched into space by the mighty eruptions!

The party repairs their airship, but as they take off the ship behaves oddly in the low gravity and thin air, and when an eagle attacks Jack, they crash into a glacier. They abandon their airship, as days in their new environment are mysteriously short, the temperature swings are extreme, and the glacier is unstable. Dangers abound: a bear attacks Jack, but Washington’s pet rooster attacks the bear and saves them by giving them time to shoot it. Mark faces an attack from a wolf pack on the ice, and barely escapes. Having left the Snowbird behind, they return to the town they first arrived at, only to be attacked again by the natives. Setting their sights on a larger coastal town, the boys and their companions convert their sleds to ice boats and set out (encountering a whole pack of bears along the way, but the wind is with them and they escape). They are disappointed to find the coastal town abandoned, but they find a beached American whaling ship—an old sailing bark—and are welcomed aboard. Further mysterious events ensue, and Professor Henderson suspects their planetoid is falling back to Earth. The air aboard the bark is getting thin, so the adventurers close all ports and hatches. They lose consciousness, and when they awaken, they find they are afloat again in the north Pacific, and head back to civilization. Their story is sneered at—until a new and mysterious island is found just south of Alaska, confirming their tale.

The Syndicate

On a Torn-Away World, originally published in 1913, was not actually written by Roy Rockwell. That is a “house name,” reflecting a practice frequently used by the Stratemeyer Syndicate, the organization that packaged the book. Edward Stratemeyer (1862-1930) was a popular juvenile writer who developed a unique system for cranking out books. He would write outlines, with other writers producing the book as work for hire under those house names. Much like television police procedurals, the books followed a standard template. They were designed as stand-alone adventures, and opened with a summary of previous adventures that was as much a sales pitch as it was a recap. Chapters ended with a cliff-hanger that was usually resolved early in the next, and the back of the dust jackets were printed with a catalog to encourage the reader to seek out other adventures. Using this formula, Stratemeyer produced hundreds and hundreds of books: series that included the Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, the Bobbsey Twins, and others that didn’t interest me, as well as the more science- and adventure-oriented books that I enjoyed best, like Tom Swift, Don Sturdy, and my personal favorite, The Great Marvel Series.

I suspect that George Lucas was a fan of these books as well. In his Young Indiana Jones television series, he selected many famous and fascinating people to cross paths with his protagonist. In an episode that also featured Thomas Edison (“Princeton February 1916” which aired in 1993), Indy actually dates one of Stratemeyer’s daughters, giving us a glimpse into Stratemeyer’s book publishing enterprise. Certainly, Indiana Jones would have fit quite well into one of the Stratemeyer adventure books.

You Can’t Go Home Again

So, upon re-reading On a Torn-Away World after a 54-year gap, what did I think of it? I can see what attracted me to the story at the age of eight: the marvels of science, the far-off lands, the attacks by fierce animals; but unfortunately, it is not very good, and actually offensive at times. While it portrays young characters building things and having exciting adventures and is brimming with technological optimism, the book is deeply flawed. The prose is awkward, and the characters wooden. Perhaps fittingly in a book prepared via an assembly line process, the two boys, Mark and Jack are the literary version of interchangeable parts, virtually indistinguishable from one another. The formula’s dependence on successive cliff-hangers keeps you turning to the next chapter, but becomes wearisome by the end of the tale. Furthermore, the book is marred by racism, terrible science, and a derivative plot.

So, upon re-reading On a Torn-Away World after a 54-year gap, what did I think of it? I can see what attracted me to the story at the age of eight: the marvels of science, the far-off lands, the attacks by fierce animals; but unfortunately, it is not very good, and actually offensive at times. While it portrays young characters building things and having exciting adventures and is brimming with technological optimism, the book is deeply flawed. The prose is awkward, and the characters wooden. Perhaps fittingly in a book prepared via an assembly line process, the two boys, Mark and Jack are the literary version of interchangeable parts, virtually indistinguishable from one another. The formula’s dependence on successive cliff-hangers keeps you turning to the next chapter, but becomes wearisome by the end of the tale. Furthermore, the book is marred by racism, terrible science, and a derivative plot.

Many books from the era when this book was written exhibit an implicit racial bias. Based on pseudo-scientific theories of social Darwinism, many in that era felt that the successes of Western civilization were due to racial superiority, and these assumptions often find expression in the portrayals of stereotypical behavior by characters from other nations, cultures, races, and ethnicities. In this book, though, what is merely implicit in other works becomes explicit: the black character’s dialogue is printed in a phonetic spelling that is hard to follow; a running joke involves his attempts to use a book to expand his vocabulary, but rather than help him with his pronunciations, the others mock him for his efforts; the narrator also refers to him repeatedly using a racial slur. The Alaskan natives are also referred to using racist terms, and are portrayed as ignorant and superstitious savages who are lost without the leadership of the oil company explorer. I lived in Alaska for two years, and never met anyone who acted the way these people are portrayed. The book, unlike other works of the era, is not openly offensive toward women—but only because it contains not a single female character. Only offhand references to women and children as they explore abandoned towns indicate that the opposite sex even exists. That absence speaks loudly without saying a word.

The science portrayed in the book is terrible, even by the standards of the age in which it was written. The idea that the two boys could have built their own airship by themselves is ridiculous. The author does not appear to understand exactly how an airship or aeroplane (as the Snowbird is interchangeably referred to) actually works. The craft hovers in mid-air, but there is never any mention of gas bags, ballast, or any of the other mechanisms used in an airship. The eruption that tears away part of the planet is described as having minimal impact on other parts of the world, which is improbable, and it boggles the mind that even the strongest volcanic eruption could push that much mass into orbit. The breakaway fragment, small in size and irregular in shape, impossibly retains a breathable atmosphere. The lower gravity of this fragment is established and described but then frequently forgotten in the narrative. The fragment is in orbit close to the Earth, but features on the planet cannot be seen except through a telescope. When this gigantic fragment of the Earth falls back through the atmosphere, it does so without generating any heat, with its flora and fauna surviving the fall. And a wooden sailing ship falls away from the fragment and descends from orbit to the ocean without burning up on re-entry, or suffering any significant damage or injury to its crew.

On top of all of the other criticisms, the plot and setting of this book is very, very similar to the 1877 Jules Verne novel, Off on a Comet. That book describes a glancing collision between the Earth and a comet, where portions of the planet break off and join with the comet as a single body. The adventurers explore their tiny new world, and when the comet’s orbit brings it close enough to the Earth that the two atmospheres interact, they use a balloon to return home. So, not only is On A Torn-Away World poorly written, it is not terribly original.

After re-reading the book, I wondered how my father had allowed me to read it, considering all its flaws; I suspect that, like me, he remembered the good parts fondly, but had forgotten the problems. I think that, if I had encountered it a few years later, I would have been more sensitive to the way different elements were portrayed: I would have known more about science, and with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 right around the corner, I certainly would have been exposed to more discussion about racial equality.

This is the first book I have revisited in this series that I cannot suggest to anyone as anything other than a historical curiosity. The exuberance, adventure, and technological optimism is far outweighed by the book’s flaws; the science is not only outdated but was preposterous even when it was written, and the blatant racism makes it unsuitable for recommendation without a disclaimer. And now, I am interested in your thoughts. Have you ever encountered The Great Marvel Series, or any other books from the Stratemeyer Syndicate? And how do you deal with outdated ideas and attitudes when you encounter them in older books?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for five decades, especially science fiction that deals with military matters, exploration and adventure. He is also a retired reserve officer with a background in military history and strategy