Although it’s a superhero story in prose, the Wild Cards saga begins with nothing less than alien first-contact. In 1946, Tachyon lands on earth alone, desperate to stop the release of a gene-altering virus engineered by his family on the planet Takis. His failure allows the virus to fall into the hands of a pulp-worthy villain who carries it high above New York City. There, in a desperate and heart-stopping sky battle worthy of the best WWII flick, Jetboy attempts to stop the release of the alien biological toxin. The young fighter pilot gives his life in the attempt, but the virus is released in a fiery explosion six miles up, floating down to the city below and carried across the globe in the upper atmosphere’s winds. On that day in NYC, 10,000 people die.

The effects of the virus are immediate and devastating, exactly as its alien creators envisioned. Each person transformed by the virus responds in a completely unpredictable manner. What can be predicted, though, are the numbers: 90% of those affected will die horrifically, 9% are hideously transformed, and 1% gain spectacular powers. The arbitrary nature of the individual outcomes lead first-responders to nickname the virus the Wild Card, a metaphor applied to the victims as well. The majority who die draw the Black Queen; those who manifest the gruesome side effects are cruelly labeled Jokers; and the few graced with enviable powers are elevated to the designation Ace. Even the “natural” and unaffected themselves will bear the label “nats.”

The history of humankind changes on September 15, 1946, ever after known as Wild Card Day. This first installment in the Wild Card series covers the event and its aftermath, exploring the historical, social, and personal impact of that day. Although some of the action occurs on the West Coast, in D.C., and abroad, most of the events center on NYC. Each story recounts the experience of a nat, a joker, an ace, or the lone resident alien, beginning in 1946 and ending in 1986.

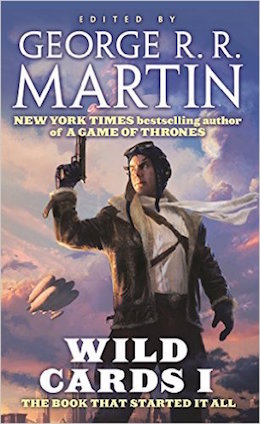

Like other shared world books, writing Wild Cards involved multiple authors. Each wrote their own chapter about a major character of their creation, interwoven into a world populated with figures imagined by the other authors. The chapters are broken up by interstitial shorts, most of which were written by editor George RR Martin. The book’s timeline ends in the year it was actually written in Real Life (1986; it was published in 1987), although three new chapters appear in the expanded edition released in 2010 by Tor.

For a book compiled from segments written by fourteen different authors, Wild Cards is remarkably consistent in its tone and thematic unity. While stylistic differences in the writing are clear, they are in no way jarring. The interludes further the world-building and add depth to the book’s tonal range, whether through the first-person oral histories of the Army men scrambling to deal with Tachyon’s landing, or the convulsive headtrip of Hunter S. Thompson in Jokertown. The shared topography grounds the plot and characters in a lived environment, especially the richly-developed NYC with its landscape of diners, Jokertown clubs, and monuments to Jetboy. Strikingly, for a tale that demonstrates historical and social change over four decades, it remains decidedly character-driven.

There’s a lot to love about this book. From the get-go, it is relentless, with the first several chapters a non-stop, heart-wrenching, chill-inducing kick to the face (featuring Jetboy, the Sleeper, Goldenboy, and Tachyon). In the following stories and eras, we’re introduced to characters that will continue to populate the series for many books to come.

Time’s Passage

For readers interested in investigating the past, the sense of history permeating Wild Cards is one of its most remarkable and consistent features. The book provides a longue durée view of a world changed forever by a single event, with the results rippling onwards through time. Our jokers and aces populate a United States rocked by social and political upheaval, dealing with issues that continue to be timely: police violence, persecution of minorities, violent protests, class conflict, government failure, and the scarring legacy of war.

Wild Card history begins in a post-WWII USA, but the spirit of each successive era suffuses the tale. The virus is released into cities filled with veterans, families hollowed by lost sons, children trained in air raid drills. Later, the crippling fear of blacklists ratchets up the tension in “Witness,” with the Red Scare and the Cold War that follows. The day that JFK died, so memorable for those who lived through it, becomes the day that ultimately births the Great and Powerful Turtle. The heady activism of the ’60s, with its demonstrations and idealism, give way to excesses of the’70s. The jokers’ fight for civil rights fairly catapults from the page. The book ends in the gritty 1980s, with Sonic Youth even making an appearance at CBGBs. As alternate-history, Wild Cards humanizes each of these crucial periods in U.S. history through the experiences of individual jokers, aces, and nats.

Historical popular culture is a presence as well. The entire story begins in 1946, after all, with a crashed spaceship and an alien in New Mexico. Tachyon may not look like a little green spaceman, but he ties traditional science fiction to the flyboy fandom of WWII war comics. The Turtle’s buddy-story with Joey brings to life the comic-collecting nerds of the 1960s’ Silver Age. The James Bond spy secrecy of the Cold War appear in “Powers,” whereas The Godfather and representations of the Mafia underlie Rosemary and Bagabond’s story. Wild Cards is authentic alt-history, but is also self-aware and self-reflexive in its shout-outs to the pop culture of its various time periods.

Class War and Persecution in Jokertown

On the surface a story about monsters and superheroes, Wild Cards is first and foremost a story about people; sadly, the jokers are treated in a way practically lifted from recent headlines. They are the most vulnerable population in the Wild Cards world, victimized and exoticized; for safety’s sake they live together in the Bowery district. Yet, even there they are beaten by police and are drafted into Vietnam in disproportionate numbers, the ultimate “cannon fodder.” They’re a population plagued by depression and suicide, until their anger finally explodes into violence and the Jokertown Riots. All our own past failings as a society come to the fore in the plight of the jokers, an eminently recognizable echo of real life. The jokers provide the dark mirror that reflects our failings back at us.

While jokers and their experience touch on the long history of persecution and civil rights in the U.S., one social area that Wild Cards does not so successfully represent is the women’s movement. The book exhibits limited roles for women and rather unbalanced gender dynamics; one wonders how the new powers brought by the virus might have impacted the history of feminism and the experience of women. What would have happened, for example, if Puppetman were a woman?

We Can Be Heroes? Even Jokers?

Such a world needs heroes most of all. Martin and his crew of contributors developed the Wild Cards universe in the mid-’80s when the superhero genre was undergoing dramatic transformations. Together with Watchmen (1986) and Batman: Year One (1987), Wild Cards portrayed comic book heroes in a newly seedy, dark, and cynical manner. It makes sense, then, that a pervasive theme of Wild Cards is the exploration of heroism in all its forms.

Time and again the wild cards universe shines a light on what it means to be a hero, even deconstructing the notion altogether. The very structure of the book allows for the contrast of heroic figures one after another. It all begins with Jetboy, the war hero and fighter pilot, who survived the battles of WWII to finally die in mortal combat in an effort to protect the fates of all. Jetboy was the last great nat hero, before his only failure ushered in the new era of the wild card.

Jetboy as the last hero of the old world is immediately contrasted with the first wild card hero, introduced in the next chapter. Croyd Crenson, the boy Sleeper, draws a reinfection by the virus every time he sleeps, shifting through new physical manifestations and powers, man to lizard and everything in between. Croyd does not fit the hero’s mold so flashily embodied by Jetboy. Frequently he’s monstrous; he becomes a drug addict; he’s a thief and a crook. But we find that his thieving supports his siblings and incapacitated parent; amphetamines allow him to patrol the Bowery’s streets to protect its vulnerable population from joker-bashers. Living in constant fear of drawing the Black Queen every time he sleeps, perhaps Croyd’s faults can be forgiven, since he relives Wild Card Day each time he wakes. Thanks to his many transformations, though, Croyd becomes both joker and ace. Even when his mind later becomes unhinged, Croyd remains a striking figure as the first hero of jokers.

Jetboy and Croyd find their opposite with the subsequent chapter, that of the first wild card villain, Goldenboy. Everything about him seems heroic, but his fatal flaw leads to an irreversible decision. As an easy-going kid with good looks, super strength, and a literal golden halo surrounding him, he becomes a member of the Four Aces, fighting for democracy and all that’s good in the world. In segregated 1947, his best friend is Tuskegee airman Earl Sanderson, himself a hero in the early civil rights movement. But whereas Earl fought for every privilege in a country entrenched in racial inequality, Goldenboy had every opportunity handed to him. As a handsome, young, white, and invincible hero, his life was one of ease, both before and after Wild Card Day. The cracks in his hero façade become evident as his success grows: he is a womanizer, a profligate spender, and ultimately proves himself incapable of standing up for what is right. His greatest and most important battle comes not in the field, against coups or enemy forces. It comes instead on safe home soil, in a civilized government building, surrounded by the powers of democracy for which he ostensibly fought. His testimony as a “friendly witness” in front of Congress reveals that, when truly powerless and afraid, Goldenboy is not a hero, but a villain: the Judas Ace.

The Wild Card authors return again and again to what it means to be a villain, or a hero, with Puppetman and Succubus, with Fortunato and Brennan, etc. The Turtle explicitly lays out why it matters, even when powerless:

“If you fail, you fail,” he said. “And if you don’t try, you fail, too, so what the fuck difference does it make? Jetboy failed, but at least he tried. He wasn’t an ace, he wasn’t a goddamned Takisian, he was just a guy with a jet, but he did what he could.”

The structural circle of heroism comes together at the end of the book with a nat, Brennan, the focus of the story once again. This time, a nat character finds himself surrounded by more powerful jokers and aces. He tries, like Jetboy—but this time, he wins.

Powers: “I’m not a joker, I’m an ace!”

Another unending source of delight and horror within the Wild Cards universe can be found in the powers manifested by those that the virus changes. The advantage of working with multiple authors reveals itself in the real diversity of wild cards drawn by the characters. The virus is infinitely flexible by its very nature, with the result that the authors are able to stretch their creativity. Some of the powers are fairly standard, such as the ability to fly, read people’s minds, or walk through walls. But most of the powers are paired with a handicap: the Turtle’s incredible telekinesis only works when he is hidden from sight within his armored, floating shell; all the various animals of New York City attend to their protectress Bagabond, who herself struggles to interact with humans and lives homeless on the streets; Stopwatch halts time for 11 minutes, but ages significantly when he does so.

It is the joker manifestations that truly add heart to the story, however, bringing a formidable pathos to the world. Many others changed by the virus exhibit physical deformities or illness. The jokers are our wounded and injured—the scarred, the disabled, the sick, those living with chronic pain and emotional despair. Even for the beautiful Angelface, the slightest touch bruises the flesh and her feet are continuously black and blue. Society treats these figures with disdain and cruelty; they are brutalized, their rights ignored, and until Tachyon opens his Jokertown clinic, they are even unheeded and shunned by the medical establishment. In the aftermath of Wild Card Day, these are the people that fell through the cracks, those who lost their voice in a world that would rather pretend that their pain does not exist. Rather than the feted aces with their superhero powers drinking cocktails at Aces High, it is the horrific treatment of jokers that makes Wild Cards feel so disturbingly real.

With this first volume, the Wild Cards series gets off to a stupendous start. This initial entry sets the stage for what’s to come in the later books, providing background to the virus and the historical and social changes it caused. Wild Cards is immeasurably enriched by the various authors who bring it a multiplicity of viewpoints and ideas, all expertly wrangled by the editor. In the end, the book’s greatest strength (and what made it stand out in 1987) is that it represents a variety of eras and a multitude of voices: ace, joker, nat.

Katie Rask is an assistant professor of archaeology and classics at Duquesne University. She’s excavated in Greece and Italy for over 15 years.

I picked up the Kindle version of Wild Cards. Does this version include the three new chapters? If not, are they available elsewhere?

I’m startled by how much of what you mentioned I didn’t (and in a few cases, still don’t) remember. Apparently I need to find me a copy for a reread, since mine is currently in storage 900 miles away.

I had totally forgotten how this series started. But I’m thinking that someone at Marvel comics must have read it because it’s been one of the major plot points for the Inhumans for the past few years.

Just a small correction, the Takisian creators of the virus never wanted it to have devastating effects. They created it to boost their own PSI powers but because of the mentioned side-effects didn´t dare to test it on themselves. And testing them on, for example, slaves or prisoners back home at Takis was also tricky, because in the 1% when it does work you would have a probably very angry ex-slave with superpowers at your hand. So they decided to test and improve their creation in all peace and quietness (and in secrecy) on specimens of this backwater planet Earth far away from Takis. If just Dr. Tachyon would not have interfered…

Great write up, I’m looking forward to the rest of them. I’ll have to look for the new version, too — were any of the new stories posted here at tor.com?

The kindle version includes the 3 new stories; (Michael Cassutt, David D. Levine & Carrie Vaughn’s stories are copyrighted 2010).

I think the reviewer’s naming of Goldenboy to be a “villain” somewhat inappropriate. As mentioned, the entire series throws the concept of hero and villain out the window. Each of the described individuals are intensely human in nature, regardless of expression of the virus, whether joker, ace, or natural human. And as humans, they are flawed as we all are. Even Tachyon, though alien, is eminently relateable, especially as he effectively goes native.

Goldenboy was flawed by inner weakness. Outwardly invulnerable, but inwardly cowardly and weak. His failure of character in front of HUAC didn’t make him a villain, simply a coward. It’s a failure he has to live with through the rest of his life in various ways (e.g. permanently banned from the Aces High restaurant.)

There are those in the Wild Card universe though that do merit the villain appellation, such as the Astronomer. That character starts to fit the hallmarks of the comic book villain a lot more solidly than Goldenboy.

In any event, as the reread progresses, I think it’s worthy of merit to be particularly careful with the hero and villain terms. In some cases they are worthy of assignation, but not in all cases, nor not in all obvious cases.

An archaeologist digs deep into the rich Wild Card stratigraphy to discover nuggets of meaning and bring them out once again into the light. Nice. I also worked in the field for a number of years, mainly in the UK, the east coast and the southwest US, but hung up my trowel for a typewriter a while back. Yes, a typewriter, not a computer. It was that long ago.

I would have loved to work in Italy. The closest I came was the Roman sewers of York, England.

As Golden Boy’s creator I may be a little biased, but I have to agree that our narrator is a little harsh where the Golden Weenie is concerned. Jack didn’t set out to conquer the world, hurt other human beings, or even run for the Senate. In fact he did everything his country asked him to do (a sure recipe for disaster, as I’m sure we all know by now). He just had this teeny little character flaw.

Though I must admit that when I wrote his story, I found myself sympathizing with him less and less. By the end of the story, I was pretty well fed up with his whining.

I think, however, that Jack’s story made the point that I intended— it’s one thing to punch an outright villain in the face, it’s quite another to fight the Imponderable Forces of History.

Is it anywhere stated that the Sleeper runs the risk of drawing the Black Queen at each iteration? I don’t remember this and it seems pretty unlikely given the number of times he changes. With a failure rate of 0.9 you don’t win Russian Roulette that many times.

There’s some more with the Sleeper and how his power works in Roger Zelazny’s story in Card Sharks, Volume XIII. As for the risk of him drawing the Black Queen, much of this, I think, is Dr. Tachyon spitballing. There’s something that happens with the Sleeper’s power a few books on which Dr. Tachyon thought was impossible too. But Croyd, being a kid, took Dr. Tachyon at his word and his fears are based on that.

As for the odds of Croyd actually drawing the Black Queen, since we lost Roger, we’ve been keeping Croyd in trust as a tribute and legacy. Plus he’s an awesome character. So I’d say Croyd is going to outlive us all.

As for Golden Weenie, Walter’s story is about heroism and bravery including true heroism and bravery. But there’s also the fact that making the wrong decision doesn’t mean that you can’t later make a right decision. I think villain is a bit harsh. The villain in the story is HUAC and especially Nixon. Golden Boy makes a spectacularly poor decision, but it also hinges on poor decisions by Black Eagle, Brain Trust, and Dr. Tachyon, all of whom are older and more worldly than Jack Braun and should have known that their decisions might come around to bite them in the ass and endanger others beside. About the only person who comes off as a pure hero is the Envoy. He was given a power that could have been used for absolute villainy–look at Jessica Jones for an example of what that power can do in the hands of someone without a conscience–and instead makes the most moral decisions he can.

@lieven

It is mentioned a few times in his later stories that Croyd at least thinks that this might happen one day. Therefore his fear of going back to sleep and his amphetamine use to stay awake. And I guess arguing with him and giving him your – correct – calculation wouldn’t help easing his paranoid drug-fueled fear. :-)

Count me as another who doesn’t regard Golden Boy as a villain, and in fact, maybe not even all that flawed, just insufficiently courageous to be a true hero. And that makes him, at worst, average.

He was never portrayed as being incredibly smart, or quick thinking, so I don’t hold it against him that he blurted out the name of Earle’s mistress. Add in the fact that he was telling the truth in a setting where I assume he was sworn to do so.

@11 – In universe, I don’t think it’s a particularly unfounded fear, though. We’ve seen his infection seemingly violate its own rules before for him (such as the time he accidentally created a communicable version of the Wild Card virus, one that could infect even those previously infected), and the disease is by its very nature chaotic and unpredictable. The odds of it happening are low, but it only has to happen once.

We could say that the chances of it happening are lower now that we know *spoilers* that his subconscious is (or can be) controlling how he manifests – but on the other hand, that might actually increase the chances of it someday happening if he’s ever suicidal, or just finally feeling his old age.

Yeah, count me in as another reader who thinks the word “villain” is a bit reductionist when it comes to Jack Braun, as villain implies a certain level of active malice and lack of remorse that does not fit Golden Boy’s personality. He is not quite a hero, not really a villain, just a guy that failed big (and tries to do the right thing in later volumes of the Wild Cards saga).

His creator himself posted here and may correct me, but I always saw Golden Boy as a sort of personification of the changes white America went through from the 1940s to the 1950s. In the beginning of the story Jack Braun seems to be this awesome guy that started as a poor farmer boy, risked his life in Europe, and is supportive of minorities and fights for Democracy and everything that is right. And then he is gradually revealed as too weak and afraid to resist when Red Scare hysteria sweeps the nation, and he ditches his minority friends, and ends up as a B-movie actor that gets rich by building shopping centers. His journey is a microcosm for America.

Like Walter says, he is a guy that did what his country told him to do, the problem is that what constituted American patriotism in the 1940s (fighting against Fascism, encouraging women to join the workforce, treating the Soviets as worthy allies) is very different from patriotism in the 1950s (bashing the Commies, enforcing conformity, sending women back to the home).

Golden Boy is a sort of a less optimistic (and superpowered) Forrest Gump, I guess.

I really enjoyed this review and am very glad to see a new generation of readers puck up this series.

I have fond and very deeply rooted memories of getting the original paperbacks of the first three Wild Card Books. Devouring them and hardly being able to wait until the next volume hit my local mall book store.

I found the books refreshing on their diversity of tone and voices, lovingly orchestrated to fit into a narrative world more realistic and raw than its contemporary counterparts. Where ‘Watchmen’ was bleak and cynical, Wild Cards was realistic, brutal, but oddly optimistic amidst its horrors and heroes. Many of the authors in this series became familiar and sought after for me upon my exposure took this series. Zalazeny and Williams especially. George Martin’s world building is made better by his team’s contributions. And tempered by it greatly it seems.

How refreshing it is to see these s viewed from a fresh generational perspective? Kate’s review is coming from one aware of the tropes and history of the genre, and shows the perspectives of an era where villainy and cowardice are no longer as subtle or obvious in their portrayals. The complexity of character that Walter John Williams mentions in his comment is now so engrained in our cultural psyche that little betrayals often feel grandiose and personal to the modern observer. Oddly enough we might have Martin to blame for that due to the world shaping effect on our perceptions his Westerosi have brought to the table. In a world of Littlefingers and Tyrions, it might be a lot easier to see Golden Boy as a Villain..

But they would be nothing without the sheer complexity and loving longevity of the Wild Cards that came before. That is the series’ legacy: the true depth of ethos and pathos on the post modern super hero tale. The fact that even beloved fan favorite characters make mistakes and have potentially works ending flaws.

I would love to hear more ongoing reviews of this whole series. Stories of the creative teams works and collaborations. Round table reviews and character discussions

The real power in this series, which I am happy to see is still going, is the diversity of its creative voices. The interplay of styles. The acceptance of nostalgia and history. Seeing Williams tout Croyd as a lasting legacy to Zelazny is one of many reasons why this series is valuable to the lexicon. Its authors created stories they wanted to read, and we needed to read them. We needed to see our weird world turned even weirder in their hands.

I look forward to more reviews of this series and hope to see more of the authors contributing to the discussions.

I remember eagerly reading through at least the first six or seven books as they were released, before college obligations took their toll on a lot of my pleasure reading time. I fell behind, but always faithfully bought each new Wild Cards volume as it came out. Finally, with this reread, I have motivation to get caught up on all those unread volumes!

I hadn’t reread this first volume since it first came out, although I’d read adaptations of some of the stories in the Epic Comics series. With the hindsight of knowing what happens in at least the next half-dozen or so volumes, some of the stories take on different weights, like the introductions of Fortunato and Puppetman.

Reading it this time around, with considerable more knowledge of history and popular culture than I had as a high school senior in 1987, I see the reflections of that popular culture in the stories a lot more clearly. The break between the dissolution of the Four Aces in the 50s, with the resurgence of heroes in the 60s–shown by the emergence of characters like the Turtle–mirror the comics industry moving away from superheroes and then reviving them around the same time frame. I hadn’t made the connection between the Godfather and the Bagabond/Sewer Jack/Mafia story, but I see it now. In particular, the new stories play into that trope; Carrie Vaughn’s Ghost Girl story plays like any number of good/normal person caught up in a night of weird events movies from that period, like Adventures in Babysitting or After Hours.

I do agree with a lot of the other posters about Golden Boy. I don’t like what he did, and I don’t consider him a particularly admirable person, but I also wouldn’t brand him a villain. He made a bad decision in a bad situation based on bad advice, and he deserves to pay the price that he does. But I don’t put him in the same class as, say, Puppetman in this book, who deliberately manipulates and hurts people for his own gain, knowing full well what he does. However, the fact that this stuff is even there to be discussed shows the depth and complexity these authors bring to the characters and stories, which is why, of all the shared world anthology series from that period, this one is still going strong.

(I do miss Thieves World, though.)

Just as a quick aside, because she’s been mentioned a couple of times in the thread, but you do all know who the Ghost Girl in her volume one story is, right?

Delighted to see this being discussed as I have no-one in real life to talk with about these books!

This first book is still probably in my top five favourites, (along with Jokers Wild, Ace in the Hole, Black Trump and Suicide Kings). And Witness is probably my favourite of all the short stories in the series. I agree with what people said here about him not being a true villain, and the story of his rise and fall is exceptionally well written. And I certainly feel a huge amount of sympathy for Jack Braun, even though I am disgusted by what he chose to do.

Special mention to Transfigurations for introducing one of my favourite characters in the series, although it took me a long time to recognise him in later appearances.

I feel Down Deep is the weakest of this set of stories. I never really engaged with Bagabond or Sewer Jack and while Rosemary is likable enough in this book her character leaves a lot to be desired in later installments.

I’m looking forward to the next installment!

I started my own reread last year. Here were my thoughts on V1:

I’ve always thought that there were two great shared world series: Thieves World because it invented the art form; and Wild Cards because it perfected it through its ability to tell epic stories and to get the writers working together rather than against each other. This is the first of the Wild Cards series. It’s had highs and lows, but it’s usually been worth reading.

Thirty Minutes Over Broadway (Waldrop: Jetboy). I love the fact that Wild Cards begins with a pulp hero. It’s a great way to show how superheroes replaced the pulps of the ’30s and ’40s. And this is a great story, both for its nostalgic feel and for its unexpected(?) ending [7+/10].

The Sleeper (Zelazny: Croyd). Croyd Cranston is a rather delightful character in Wild Cards because of the fact that he can sleep through the decades and the fact that he’s always changing. He almost seems like a reaction to John Brunner’s Enas Yorl in the Thieves World series. It’s also interesting to see our first hint that Wild Cards is going to be a dark superhero series, thanks to Croyd’s decision to become a thief and a drug-user. Overall, a strong story to open up the post-virus age of Wild Cards [7+/10].

Witness (Williams: Golden Boy). One of my favorite stories in the entire Wild Cards mythos. Williams manages to fill it with a sense of history and a real pathos. You understand why Braun did the things he did, but you also understand his regrets. He proves he’s not a hero, but that’s still what he desperately wants to be. Yeah, this same story has been done in DC’s JSA (minus the betrayal), but Williams gives it depth and humanity [9/10].

Degradation Rites (Snodgrass: Tachyon). This is a very nice complement to “Witness”, showing how tightly the Wild Cards stories would cleave together. But it’s also a rather magnificent look at the character of Tachyon: who he is and what he’s willing to do. There’s still a moment in this story that shocks me after multiple reads over many years [8/10].

Captain Cathode and the Secret Ace (Cassutt: Karl von Kampen). New Story. I was always sad that Wild Cards so quickly moved out of its historical foundation into the modern day, so I was thrilled when I heard that the new edition of this first book had three new stories in it. And this one is … OK. Sure, it’s set in the 1950s, and it does a good job of linking up historical events. But the actual story of an actor gone wrong is not terribly thrilling. I liked the increased emphasis on the discrimination toward Jokers, which comes across better it did in the original stories of this era, but that was the only thing I found particularly notable [6/10].

Powers (Levine: Stopwatch). New Story. I groaned a bit at the story of yet another Ace in hiding, but fortunately that was dealt with relatively quickly. What comes after is a great bit of history (the 1960 U-2 incident), tied into the Wild Cards world. It’s really nice to get a ’60s look at the Cold War, with the story opening up new vistas for Wild Cards in a way that “Captain Cathode” didn’t. We also get an interesting new Ace. My only real complaint is that they introduced two far-seeing Aces in two stories (von Kampen and Powers) and failed to tie them together, displaying the weaker continuing of these new stories, compared to the original [7/10].

Shell Games (Martin: Turtle, Tachyon). Turtle was always one of my favorite characters in Wild Cards, probably because he’s such a stand-in for the fans; he’s a gawky fan himself, who decides to be a hero … but has to figure out the natural problems that arise. And, this is a great intro to him. However, Tachyon also gets a great plot, resolving his issues from earlier in the novel in a really believable way. The result is both a great story and a great example of how tightly connected Wild Cards would be. [8/10]

The Long, Dark Night of Fortunato (Shiner: Fortunato). What better way to enter the ’70s than with a blaxploitation story? Like the best shorts in Wild Cards, this one really shows off its time period. And the story? It’s a nice, but simple tale of gaining powers while investigating a murder. With all that said, I’m not fond of Fortunato as a character. And it’s not just that he’s a super-pimp. (But he is totally a super-pimp.) It’s that he’s so at odds with the feel of the series up to this point. I mean we had darkness back as far as Croyd, but something about Fortunato really puts things over the top by putting an “earthier” element as the core of his character. Adult superheroes? Great. Disturbing sexual fantasies? Not so much. Anyway, here he is [6/10].

Transfigurations (Milán: Radical). Radical is an interesting parallel to Fortunato. They’re from the same era (in fact, I think the stories should be reversed in the collection because this one better depicts the ’60s, despite their overlapping time periods) and they both gain their powers in less socially acceptable ways: Fortunato from sex and Radical from drugs. Both stories pushed the series in a earthier, in-your-face direction. But I think Radical works much better; he feels like a more believable member of the Wild Cards universe. And this is a very nice intro. Aside from a few minor gaffes about Berkeley and San Francisco, this is a great look at the dying hippie culture of the ’60s, with well-defined and interesting characters. Not only does Milán create an interesting confrontation, but he also ends the story on a great note which just begs for more stories going forward [7+/10].

Down Deep (Bryant & Harper: Bagabond, Sewer Jack). Though I questioned the direction and taste level of Fortunato’s introduction, this is the only story in the original Wild Cards that feels like a failure. It’s just such a mishmash. It’s got four different major characters (Rosemary, Bagabond, Sewer Jack, C.C.) and they circle around each other in unlikely ways without forming a coherent plot. Worse, the Aces seem like a top-ten list of New York clichés: an alligator in the sewers (Jack), a bag lady (Bagabond), and a haunted train car (C.C.). The mob as presented here seems like a very over-the-top cliche too. Overall, this story just doesn’t work as a whole because there’s too much jammed together and most of it isn’t good [3/10].

Strings (Leigh: Puppetman). My other favorite story in this first volume. That’s largely down to Puppetman; Leigh does such a great job of depicting a sociopath, and then makes that terrifying thanks to Hartmann’s powers. But beyond that it’s an intriguing story of politics and manipulation, set around a major historic event. It’s a great story and a great piece in the historical puzzle of this first volume. Leigh also manages to take the earthier tone of these later ’70s stories and to really push it as an extension of the superhero genre without making the whole story about it. [9/10].

Ghost Girl Takes Manhattan (Vaughn: Ghost Girl). New Story. The last of the new stories, and the best of them. Vaughn does a great job of evocatively capturing the New York punk scene as the ’70s slide into the ’80s. His character, Ghost Girl, is also quite fun; it makes me sad that she’s stuck in the ’80s, and so we’ll probably never see her again. The story itself is also a fun caper. It doesn’t go much of anywhere, but you can forgive that because it’s got Croyd in it (and generally feels like a strong part of the Wild Cardsintegrated universe in a way that the other new stories missed) [7+/10].

Comes a Hunter (Miller: Yeoman). Because of the Wild Card virus, the Wild Cards series has focused almost exclusively on powered Aces (and Deuces) and on their less-fortunate Joker brethren. This first Wild Cards anthology thus ended with a breath of fresh air by introducing Yeoman, a “nat” hero. Yeoman is very much the archetypical gritty Green Arrow, but what’s impressive is that this story predated both Mike Grell’s Longbow Hunters and the much-more-recent Arrow TV show. But the Oliver Queen from those stories: the philosophical, semi-mystic vigilante? He’s on full display here, and Miller presents the story well [7/10].

In some ways, this first Wild Cards was like the Thieves World that predated it. Its connectivity was very thin, as its main goal was just to reveal 40 years of history. However, you could already see the tighter “mosaic” story-telling that would follow thanks to the setups, all in this volume, of several of the epics that would follow, particularly the fights against Tiamat and Puppetman.

On average, these stories rate four stars, with just one disappointment (“Deep Down”) and several stories that rise above that (“Witness” and “Strings” and to a lesser extent “Degradation Rites” and “Shell Games”). It’d probably rate 5 stars as a whole based solely on the individual stories, but if not it definitely rises up to the level based on the epic scope of this volume … and by what it puts into motions for future volumes.

As for the new edition with three new stories: it’s OK. The new stories are generally of lower quality than the originals (“Ghost Girl Takes Manhattan” excepted) and none of them add much to the overall narrative. But I loved to get more looks into the history of Wild Cards, and Ghost Girl’s was particularly strong for its look at the ’80s.

@20 great reca

Only, Ghost Girl is not stuck in the 1980’s. I’ll see if further discussion resolves this mystery before saying more

I’d forgotten all about Wraith when I reread Wild Cards I, although I had a niggling feeling that her power was a leetle repetitive. I’d have to reread the new story to pick up the clues.

There’s a lot to keep track of, but in my opinion a lot of the charm in wild card comes from the attention we pay to the little things.

I always thought that Ghost Girl was Jennifer MAlloy, aka Wraith, before she met up with Brennan/Yeoman.

And now I really want to see that discussion about Yeoman… an archer/vigilante with no powers or Wild Card, just a nat with a bow, fighting crime, and how well he did or didn’t mesh with the setting.

Yeah, you’re exactly right.

From the beginning of the project I had wanted to do a story-line about that very subject: a normal guy (if with some extraordinary capabilities) who had to function in a world of aces. And with no boxing glove arrows. Of course, how well it all came out is subject to discussion, but I was pretty happy with his story arc which I ended in a section of DEATH DRAWS FIVE. (Interestingly, or maybe not, is that that whole segment is set on Onion Avenue, the county road where I lived and grew up on, and its environs, and is entirely accurate in depiction [except for the commune of snake handlers on Snake Hill, though there was a Snake Hill about two miles from my house, which I would run past when I was doing road work while in high school.]) The difficult thing about it was that I had to balance the needs of his personal story with that of the over-all plots of the books, so I had to get him involved with things like helping to save the world from the Swarm invasion. But that is all part of the fun and challenge of being involved with Wild Cards. Advancing your individual plot while still being a team player, which is something I’ve at least attempted to do during the entire project.

By the way, have you seen the cover art for DEAD MAN’S HAND, which will be coming out in June? Absolutely terrific depiction of Brennan and Jay Ackroyd. Komarck sent me a file (since his work exists only on computer) and I took it down to a print shop and had it blown up to a poster size, which is framed and hung on a wall. Best cover I’ve ever had for one of my characters.

@26 Death Draws Five is one of my favourite WIld Cards book, it was great to see Yeoman back again!

Thanks.

I think the comments about Golden Boy not being a villain are well-warranted and, if I could go back in time, I would call him a “failed hero” or something along those lines. Not coming from the world of comic books myself, perhaps I played too loose with the term. I do think, though, that the negative repercussions of his actions were very real and shouldn’t be downplayed. He ruined (many) lives and he indirectly caused Blythe’s death, all because he was afraid to go to jail. While that does not make him a really, really bad dude, it does indicate that he chose to condemn his best friends (and anyone on a potential wild card register) rather than be labeled a criminal. To me this serious flaw in his character is difficult to forgive. It makes me question what was ever heroic about him. At the same time, he made a mistake and would obviously take it back if he could. We’ve all made mistakes in the rush of a moment, too. His mistake and guilt are some of the reasons that Golden Boy’s character is so compelling.

I actually see Golden Boy as something of a tragic figure. Unable to rise above his character flaws, he was forced to make a horrible choice. I wonder if Mr. Williams had Elia Kazan in mind when he created this character. Kazan, another former actor-turned-director, described himself as taking “only the more tolerable of two alternatives that were either way painful and wrong” when deciding whether to testify before HUAC. And like Golden Boy, Kazan suffered the loss of friends and the contempt of colleagues