I don’t know how Kathryn Bigelow is still making movies. Don’t get me wrong—I’m very, very glad she is, because she’s one of the best directors around. Up until 2008’s The Hurt Locker, Bigelow directed movie after movie that went unnoticed or unappreciated. While a box office success, Point Break doesn’t receive nearly enough credit for being one of the most stylish action movies to come out of the ’90s. Near Dark—my goodness, Near Dark is vampire movie paradise. The Weight of Water is fascinating.

And then there’s Strange Days, which is Bigelow at her best, delivering a sci-fi thriller/noir that’s prescient even now, in 2017. In 1995? To say it was ahead of its time would be like dropping a 1967 Chevelle into Victorian England and calling it advanced.

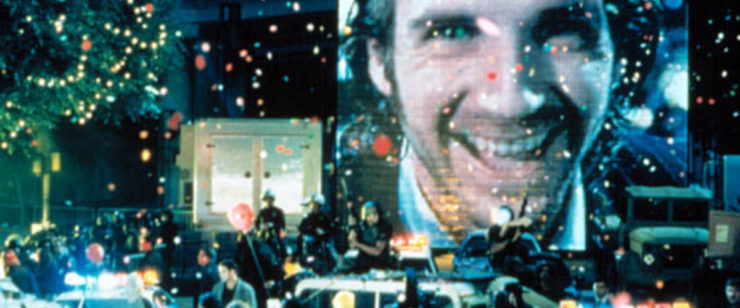

Strange Days, from a bird’s-eye view, is this: at the dawn of the new millennium, the United States is a powder keg waiting to blow. Los Angeles, from what we see, has pretty much become a police state, with armored officers enforcing checkpoints and an occupation-type control over the crime-infested city. Race relations are bad, the economy is bad, the power structure is broken, and it seems to only be a matter of time before the entire thing we call society comes undone. Keep in mind, Strange Days was released just three years after the L.A. riots, which were sparked by Rodney King’s beating—captured on tape—at the hands of the LAPD; it’s safe to say that Bigelow and James Cameron, who wrote and produced the movie together, had that chapter of U.S. history on their minds when crafting their story.

We follow Lenny (Ralph Fiennes) through this crumbling L.A. as he peddles the current drug of choice: SQUID discs, which are kind of like a Vine that allows users to not only see the world through someone else’s eyes, but to experience what they experienced when the video was made. But when Lenny is delivered a disc that shows the rape and murder of Iris, a woman he knows, he’s plunged into a plot that carves right into the heart of the city’s problems with race, police brutality, and corruption.

It’s hard to describe the plot beyond the basics, because like any good noir, there’s a lot of twists and turns, double-crosses and surprise reveals. It’s arguably a little too much, since by the end it’s difficult to not only make sense of the plot, but it’s also a challenge to figure out how everything connects, logistically. But, again, this is how noir often functions. It’s more about the journey than the resolution—if that wasn’t the case, The Big Sleep wouldn’t be considered one of the best movies ever made. That doesn’t excuse the movie’s problems, however; it lacks focus, and it would have been greatly served by a strong hand in the editing room. The movie doesn’t really start until a quarter of the way through, as the opening 20 minutes (or so) are focused on building the world and positioning the characters rather than developing the plot; it would have been more effective if the inciting incident—Iris’s murder—happened sooner, and the murder of Jeriko One (a famous rapper/activist) could have been better integrated into the narrative and given more weight.

Despite those shortcomings, the journey of Strange Days is one that’s worth taking. Bigelow’s take on institutional racism, police brutality, and the evolution of society toward a military state was bold and sobering in 1995, and it remains salient (unfortunately) today. One of Bigelow’s greatest strengths as a director is her willingness to take unflinching looks at things most people would rather turn away from, and that quality serves her very well in Strange Days. In the hands of a director lacking Bigelow’s fearless gaze, Strange Days would have been a forgettable movie, but she elevates it to so much more. And this doesn’t even account for the film’s forward-thinking take on addictive technology and voyeurism, which was downright prescient.

It’s unsurprising that the movie was polarizing when it was first released and continues to elicit the same mixed response. The plot is problematic, there’s no denying it, and there are iffy performances (particularly from Juliette Lewis) that encumber the film. But the best parts of Strange Days come from its ambitions to train its crosshairs on difficult topics. Bigelow forces the issue of racism in a challenging and unique way, using voyeurism as a means to question our own involvement with this epidemic. After all, the King beating wasn’t just a landmark because of the incident itself—it became a landmark incident because it was caught on film. It was played—and viewed—over and over and over. The philosophical underpinnings of what it means to experience such a terrible moment by watching it gives the Strange Days viewing audience the same sense of unease Lenny feels when watching/experiencing the SQUID disc of Iris’s death. He walks away feeling both complicit and violated, disgusted and responsible. Combining those elements together—the active and passive act of voyeurism with the exposure King’s recorded beating brought to institutional racism—makes Strange Days a courageous, important movie, and it deserves a world of credit for that to this day.

And let’s not forget that Strange Days also showcases Juliette Lewis trying to play Courtney Love, Tom Sizemore in a wig, and Michael Wincott playing…Michael Wincott. A courageous movie, indeed.

Michael Moreci is a comics writer and novelist best known for his sci-fi trilogy Roche Limit. His debut novel, Black Star Renegades, is set to be released in January 2018. Follow him on Twitter @MichaelMoreci.