For a hot second, Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ space opera comic book series Saga is literally about chasing hope across the universe. After surviving two separate attacks on their lives and that of their unnamed newborn daughter, Marko encourages his wife Alana that they will continue to survive, because “this time, we have something else on our side. We have Hope.”

“If you think I’m calling my daughter that,” Alana snarks, “I want a divorce.” In the same panel, our series’ narrator confirms that her name is actually Hazel and that she does indeed survive to adulthood. While she narrowly avoids being named for a virtue, Hazel acknowledges that she nonetheless represents something big: “I started out as an idea, but I ended up something more.” An idea, from the minds and loins of her star-crossed parents, to end the decades of bloodshed between their warring races. It’s in her name, for the shifting color of her eyes; it’s in her mix of horns and wings, imprinted with the genetics of both Wreath and Landfall, the warring home worlds of her parents. A truce, a middle ground, a universal concept that can be shared rather than owned: peace.

Unfortunately, peace doesn’t fit so well within the agendas of the Landfall/Wreath war, which means that from the moment of her birth, Hazel and her parents are on the run.

Minor spoilers for Saga Volumes One through Seven.

In a recent essay for Wired, Charlie Jane Anders posits that the renewed interest in space opera is due to the fact that “[t]he real world can be frightening right now. Space operas celebrate the idea that, come what may, humanity will one day conquer the stars and brave new worlds. It offers an escape, and, [Kameron] Hurley notes, a glimpse of more hopeful futures.” But in Saga, that glimpse towards hope is usually obscured by the details of the war. As Hazel explains it, her mother’s planet, Landfall, has always been locked in conflict with its moon, Wreath, her father’s home:

When the war with Wreath started, it was fought amidst the general population, in cities like this one, Landfall’s capital. But because the destruction of one would only send the other spinning out of orbit, both sides began to outsource combat to foreign lands. While peace was restored at home, the conflict soon engulfed every other world, with each species forced to pick a side—planet or moon. Some of the locals never stopped thinking about the battles being waged in their names on distant soil. Most didn’t really give a shit.

While an odd detente exists at ground zero, the war has spiraled out so deep into the reaches of the universe that it is self-sustaining, neverending, the epitome of what were we fighting about in the first place? on a galactic scale. Yet all it takes to threaten to halt that endless, bloody cycle is the fortuitous meeting of an inmate and a guard, a Secret Book Club with a subversive metaphorical pulpy romance novel, and just enough chemistry.

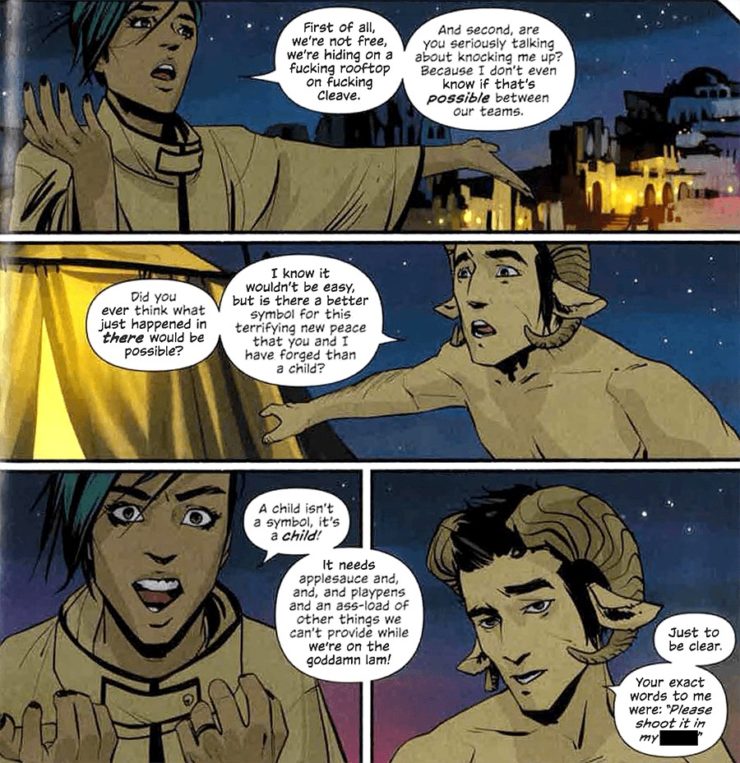

Alana is terrified at the notion of bringing a child into the world(s) during wartime, and argues that it’s probably not even physically possible between their races; propaganda has characterized any preexisting hybrids as “rape babies” that supposedly died shortly after exiting the womb, more anonymous victims of war. But Marko counters, “Did you ever think what just happened in there would be possible? I know it wouldn’t be easy, but is there a better symbol for this terrifying new peace that you and I have forged than a child?”

“A child isn’t a symbol, it’s a child!” Alana argues. Not quite—Hazel is a symbol, but she’s also a target. For some who have devoted their lives to chasing that same hope, catching up to it means not experiencing it but snuffing it out. Yet each of this family’s pursuers are chasing down their own hopes, or stakes, along the way. Prince Robot IV needs to bring in the defectors and their daughter so he can get home in time to be a proper father himself. Gwendolyn was ostensibly dispatched by political forces to keep this unholy union hush-hush, but The Will quickly establishes that she “has some skin in this game” due to her and Marko’s broken engagement. For his sake, The Will is avenging the senseless death of a loved one. Ironically, in trying to capture one little girl, he winds up freeing another: Sophie leaves behind a brutal future on Sextillion in order to become first his protege and then, as she ages from a child to a preteen, Gwendolyn’s sidekick. She gets her future back.

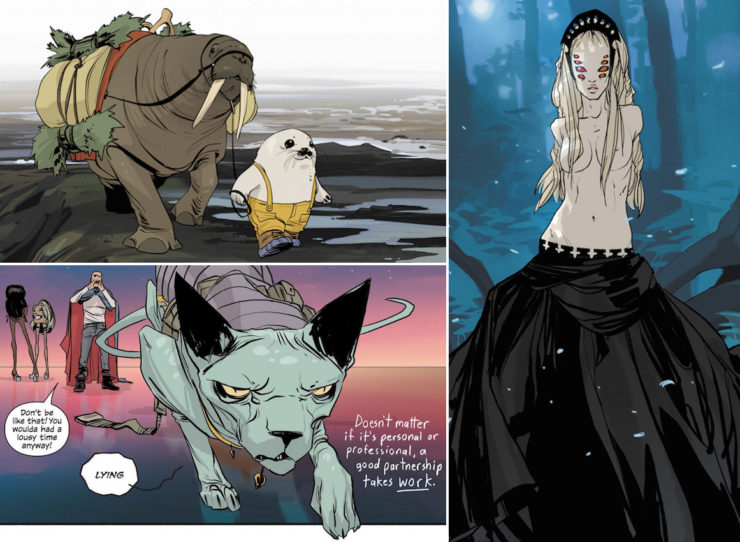

What a brilliant conceit to craft this series around a chase. It’s a familiar one for Vaughan, as Y: The Last Man (published a decade earlier) shares the same general structure: Yorick travels the world for five years searching for Beth, along the way meeting all manner of women (and a few men) with whom he wouldn’t have interacted had the plague not occurred. Similarly, in following Alana, Marko, and Hazel—and the various chosen family and enemies they pick up along the way—we are exposed to the incredible diversity of this universe. Prince Robot IV, the royal war veteran torn between giving in to the PTSD that makes his screen glitch and staying alive for the sake of his infant heir; the captivating, nightmarish Venus de Milo-meets-arachnophobia aesthetic of The Stalk; one-eyed author D. Oswalt Heist, hiding subversion in pulpy romance novels; a planet-sized infant that hatches from an egg called a Timesuck; the giant toad battle stomper; a comet filled with a dozen little rodent refugees; an adorable seal creature named Ghüs; LYING CAT. None of which would exist, let’s be real, without Staples taking Vaughan’s already bonkers descriptions and just running with them.

Nadia Bauman (of Women Write About Comics) puts it best when she says that “Saga’s world is inhabited by creatures of weird origins, yet it’s not a freak show for readers’ amusement. […] Saga teaches us that people come in different colors, shapes, and sizes—isn’t it an apt idea for our intolerant world?”

What makes Saga live up to its name is, ironically, these more mundane pockets of time—we’ll skip ahead a year or more, to a point in which the family has been able to stop running, breathe a little easier, and put down the shallowest of roots. And here’s where Saga invokes the “opera” part of “space opera”—that is, soap opera-esque subplots about Alana struggling to be the breadwinner while acting in the pro wrestling serial (full of soapy plots) Open Circuit and getting hooked on Fadeaway; about Marko flirting with temptation in the form of a sweet neighbor making eyes at him at the playground. The space battles may be the big moments of the series, but it’s the little moments between battles where everything changes. (This has been a running theme for Space Opera Week, in articles from Ellen Cheeseman-Meyer, Liz Bourke, and others.)

This little family’s flight puts them in the path of countless other aliens from either side of the war, as well as noncombatants: teachers, reporters, photographers, ghosts, prisoners, actors, refugees. Take Saga Volume Six, in which most of Hazel’s story takes place in a classroom for children of prisoners. There, the teacher Noreen (who resembles a praying mantis in a turtleneck) takes young Hazel under her wing, trying to understand what trauma this strange child is blocking by using the word “fart” as an expletive and drawing silly pictures instead of anything of substance. When Noreen gifts the child with a picture book, Hazel bursts into tears—her mother gave her the same book, before they were separated. Hazel gives Noreen her own gift: D. Oswald Heist’s A Night Time Smoke, one of many copies her grandmother bought. Flipping through the Heist, Noreen shares with Hazel her first memorable lesson:

In some ways, these quotidian moments of connection between different-looking people are almost as subversive as the first time Alana read aloud a passage from A Night Time Smoke to Marko, because they’re bad for The Narrative. The overall faction of forces on Wreath calling the shots (including setting into motion the chase for Marko and Alana), The Narrative thrives when all of its players are isolated from one another—ideally by their own choice, their own disdain for anyone who looks or sounds different from them—but all tuned to the same channel of propaganda.If not for the manhunt for Hazel that forces her parents to both hunker down and hide and run for their lives, the rest of the galaxy’s inhabitants would all still be living in their own bubbles, lacking the exposure to different and nuanced perspectives.

Bauman sums up the true hidden message of Saga:

In Saga, the war is the only villain, which stands for everything that’s against characters’ well-being, e.g. xenophobia, intolerance, black-and-white vision, and strictly prescribed roles. It not only intensifies bigotry in the book’s universe; in its core, the war is bigotry, a metaphor for it. The way the novel exposes the Landfall-Wreath conflict hints that it’s more likely a literary trope than a real war: the story hardly shows any military actions, the reasons are unknown, and all we can see is mutual hate and resentments.

[…]

How to win if the war itself is your enemy? Marco [sic] and Alana choose inaction. When they flee from the bloody feud they actually claim their right to choose life, love, friends, and foes by their own free will. Unable to find a safe place, the couple creates a tiny microcosm of the family, where they can raise their daughter Hazel and instill her with their values. It’s their method to beat the system, and it’s pretty similar to one of Frederic Henry and Catherine Barkley from Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms. The soldier and the nurse “declare separate peace” exactly the same way. The happy difference is that Alana and Marco [sic] succeed, i.e. their child, a symbol of a world without the war, survives. In some sense, they have already won, although the journey is not completed. Their story is important for all of us, because it contains a formula of how to put an end to hate and hostility in our universe.

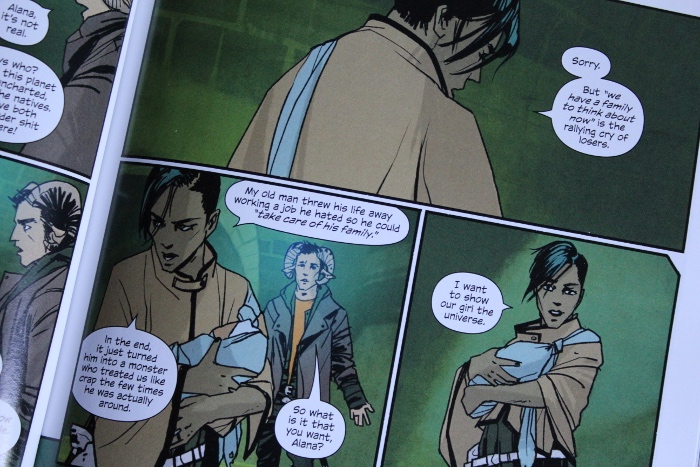

Marko and Alana were raised to fight the Landfall/Wreath war because of tragedy (all of her uncles were cut down in a single battle) or duty (his parents showed him a flashback of the bloody wars on their soil to infuse him with hatred of the wings). But once they find each other, they decide against fighting the war as it exists and fighting against the war, against bigotry, instead. But it’s not enough to create a child out of their blended genetics and shared histories. It’s not enough for their little microcosm to be pulled apart, to be reunited, to survive. Initially Marko argues for keeping their heads down, claiming they have a family to think about now. Alana immediately and emotionally counters him:

If they didn’t go on the run, Marko and Alana might have raised Hazel on the civilian world of Cleave, keeping their heads down and thinking about the war only when they were trying to skirt the battle as it worked its way around their planet. They might have been safe, but they would be no closer to bringing about peace. In order to do so, they must expose themselves, and therefore others, to the diversity of the universe. By setting off for destinations unknown, by chasing their own hopes for someday-peace and making themselves a moving target, they expand everyone’s horizons.

Natalie Zutter is going crazy waiting for Saga Volume Eight. Find her on Twitter and Tumblr.

It is BKV’s Saga. It’s BKV and Fiona Staples’ Saga. Please stop artists who are co-creators, co-owners and most importantly the co-authors of comics. It’s really uncool and belays a complete misunderstanding of how comics are read.

Curious that one profanity is blacked out, but another is not.

thanks for this article. Despite having heard how great Saga is I hadn’t read it – somehow I got the impression it was about mythical creatures living in our world. No idea it was a space opera.

Anyways, after reading this I started reading the digital version and its awesome.

I have never been a big follower of graphic novels, but for some reason I got clued into Saga a while back and found it absolutely fantastic. Inventive and heartwarming and naughty all in one amazing visual package. My only concern has been that, in recent issues, the stories don’t seem to be going anywhere. But maybe that’s just because I’m less familiar with this genre.

@@.-@ Yes, the story is going nowhere. It i a stable of comic series in general and of TV series. They start out with a bang, great premise, great characters, great plot or great world building, and then the story is stretched thin because they have to make sure the series fills out a specific number of volumes (10 volumes for Saga, 23 episodes a season for TV series). Filler storylines, characters (episodes) are used and it dilutes the quality of the work.

Saga as been on filler mode since about volume 3. BKV is on cruize control. I’m sure he knows where he wants to go and how he plans on ending the story, but he doesn’t know how to get there and now it is pretty boring. The same thing happened with Y: The Last Man, also by BKV. It started with a great premise, all men except one die suddenly and only women are left in Eart, but past the two first volumes, it was just wandering aimlessly.