Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

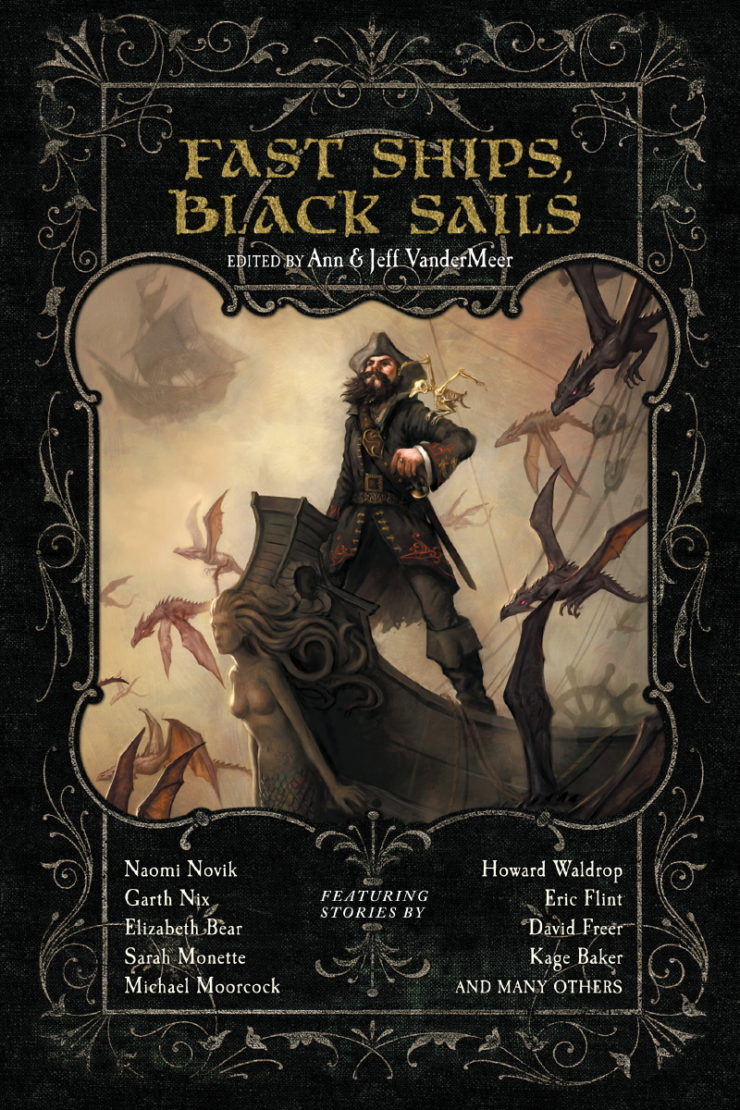

Today we’re looking at Elizabeth Bear and Sarah Monette’s “Boojum,” first published in Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s Fast Ships, Black Sails anthology in 2008. Spoilers ahead.

“Black Alice was on duty when the Lavinia Whateley spotted prey; she felt the shiver of anticipation that ran through the decks of the ship.”

Summary

The Lavinia Whateley (aka “Vinnie”) is a bad-ass space-pirate ship. She’s also a living creature, an “ecosystem unto herself,” an enormous deep space swimmer with a blue-green hide impregnated with symbiotic algae. Her sapphire eyes are many; her great maw is studded with diamond-edged teeth; her grasping vanes can furl with affection or grapple a “prey” ship beyond hope of escape. Like all Boojums, she was born in a cloud nursery high in the turbulent atmosphere of a gas giant. Mature, she easily navigates our solar system, skipping from place to place. Eventually she may be capable of much greater skips, out into the Big Empty of interstellar space itself.

Her crew lives inside her, under the iron command of Captain Song. Black Alice Bradley, escaped from the Venusian sunstone mines, serves as a junior engineer but aspires to “speak” to Vinnie as the captain and chief engineers can. Because, you see, she loves her ship.

One day Vinnie captures a steelship freighter. After Song’s “marines” take care of the crew, Black Alice goes on board to search for booty — all valuables must be removed before Vinnie devours the freighter whole. She discovers a cargo hold packed with silver cylinders she recognizes too well — they’re what the dreaded Mi-Go use to pack human brains for transport. Captain Song rejects Black Alice’s warning about bringing the canisters aboard Vinnie. After all, the Mi-Go are rich miners of rare minerals — let them pay Song ransom if they want these particular brains back.

Sensitive as she’s grown to Vinnie’s “body language,” Black Alice begins to notice the Boojum’s not quite herself. When Song directs her toward Sol, Vinnie seems to balk. When Song directs her out toward Uranus, Vinnie’s birth planet, she travels eagerly. Does Vinnie want to go home? If they continue to frustrate her, will Vinnie go rogue like other Boojums that have devoured their own crews?

Chief Engineer Wasabi sends Black Alice on an extravehicular mission to repair a neural override console anchored to Vinnie’s hide. Black Alice hopes the repairs will make Vinnie feel better — certainly the Boojum’s flesh looks inflamed and raw around the target console. The console casing is dented, debris damage Black Alice thinks at first. Then, watching Vinnie vane-lash her own flank, she wonders if the Boojum damaged the console herself, trying to sweep it off as a horse would tail-swat a tormenting fly.

Black Alice asks Wasabi if they can move the console to a less tender spot. Leave that “governor” alone, he replies, unless she wants them all to sail into the Big Empty. Is that what Vinnie longs for then, to begin the next phase of her evolution in the space between stars?

Just get the repairs done, Wasabi says, because company’s coming. Not welcome company, either, Black Alice sees. Hundreds of Mi-Go, hideous as the pseudoroaches of Venus, approach on their stiff wings, bearing silver canisters. Nor do they come to negotiate for the captured brains. As they enter Vinnie, Black Alice hears the screams of her crewmates. She hopes they’re dying but fears their fate will be worse — the Mi-Go have brought along canisters enough for all.

Black Alice has begun to communicate with the Boojum via hide pulses and patch cables; she explains what’s happening to the crew, what will soon happen to her, how she’s detaching the governor console so Vinnie can go free. Vinnie offers to help Black Alice. To save her. To eat her. What? Well, better that than madness in a can.

Black Alice enters Vinnie’s vast toothy mouth. The teeth don’t gnash her, but the trip down Vinnie’s throat crushes her ribs.

The blackness of unconsciousness gives way to the blackness of what? Death? If so, death’s comfortable, a swim through buoyant warmth with nothing to see but stars. Vinnie speaks to her with a new voice, “alive with emotion and nuance and the vastness of her self.” Black Alice realizes she’s not just inside Vinnie. She is Vinnie, transformed and accepted, embraced by her beloved ship. Where are they going?

Out, Vinnie replies, and in her, Black Alice reads “the whole great naked wonder of space, approaching faster and faster.” As Vinnie jumps into the Big Empty, Black Alice thinks how tales will now be told about the disappearance of the Lavinia Whateley, late at night, to frighten spacers.

What’s Cyclopean: The Mi-Go have “ovate, corrugated heads.” That’s a nice way of saying they’re rugose.

The Degenerate Dutch: Humanity may colonize the solar system, but we’ll still take the most traditional aspects of our cultural heritage with us. For example, slavery.

Mythos Making: Naming your spaceship after Wilbur Whateley’s mama is an interesting life choice. So is crossing the Mi-Go.

Libronomicon: Pirates aren’t much for reading.

Madness Takes Its Toll: It’s rumored that brains go mad in Mi-Go canisters. Doesn’t decrease their value on the black market, though.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

“Boojum” is the first (I think) of an irregular series of Bear/Monette Lovecraftian space opera stories. Together, they address the pressing question of what, exactly, it’s like to become a spacefaring species in a cosmic horror universe. And provide the answer: doesn’t a really close-up view of an uncaring cosmos sound like fun?

It does, at least for the reader. “Boojum” manages to be both fun and dark, melding three separate subgenres (along with the space opera and the Lovecraftian horror, it’s a perfectly cromulent pirate story) into a world where you can worry simultaneously about your suit’s air supply, your keelhauling-prone tyrannical captain, and Mi-Go brain surgeons. Good times.

The Mi-Go are the element of the story taken most directly from Lovecraft. They’re much as described in “Whisperer in Darkness,” including the mention that they, like the boojums, can travel through space freely in their own flesh. And that they have… ways… of bringing others with them. I tend to privately gloss over the specifics of how brains get into canisters in “Whisperer,” because otherwise I get distracted by the screaming of my inner neuroscientist. But if you’re not going to gloss, it’s best to go all the way in the other direction, so I kind of love that they stink up the hold with their fleshy putrescence, and that Black Alice actually opens one up and sees the extracted brain in all its glorious creepiness.

The major change in “Boojum” is the ambiguity of those brain canisters. In Lovecraft’s original, we hear directly from those the Mi-Go have disembodied. They seem brainwashed (so to speak) but coherent, and pretty excited about getting to see the sights of the universe. We never do find out whether “Boojum’s” brains are willing guests or prisoners, companions or trade goods. We just know that the Mi-Go don’t take kindly to them being pirated.

The space opera setting is lightly sketched, giving only the basic background needed to enjoy the ride. Humanity has spread around the solar system, collecting all manner of resources that can be both traded and, um, gently borrowed. There’s more than one way of getting around, with steelships both more common and more slow than the omnivorous bioluminescent horrorships favored by our pirate protagonist. Have I mentioned that I love organic spaceships? They’re such an unlikely trope, but there they are in Farscape and the X-Men’s Brood Wars and random Doctor Who episodes, giving literal embodiment to the sentimental metaphor of ship as living member of the crew. Or poorly treated slave, all too often. Maybe take a lesson from the Elder Things about enslaving entities that can eat you when they revolt?

Calling them boojums invokes yet another corner of literature—the absurdity of Lewis Carroll a distinct flavor from the type of irrationality invoked by Lovecraft. Yet another card in Bear and Monette’s fistful of genres. Maybe the point is that you can’t count on even the level of predictability found in cosmic horror; no danger is off the table. Similarly, there’s little pattern to the naming of boojums. They all carry human names, but not from the same source. Still, Lavinia Whately is an interesting choice. Either this is a world containing both the Lovecraftian canon and real Mi-Go, or that’s the equivalent of naming your ship Mother Mary. I’m inclined toward the latter interpretation, and wonder whether this is an alternate world in which the unmentioned Earth has been “cleared off.”

Anne’s Commentary

After the excitement of Wiscon, or more pertinently, the postcon exhaustion, it was going to take quite the story to perk me up. Count me perked – what an invigorating tonic “Boojum” was, almost as potent as one of Joseph Curwen or Herbert West’s pick-me-ups!

I already had Elizabeth Bear to thank for my inspiration at the Wiscon panel, “Alien Sex Organs.” Armed only with yellow and blue modeling clay and shiny beads, I created my very own shoggoth in bloom. Now I’m itching to do a model of Vinnie. Bear and Monette mention the cloud nurseries in which young Boojums grow, but where do young Boojums come from? Are the great space swimmers sexually dimorphic? Trimorphic? Asexual? Do they seek the Big Empty because it’s not so empty after all – plenty of potential mates out there? Just the kind of pleasant puzzlement a really good alien evokes in the reader’s mind.

The marriage of space (pirate) opera and Cthulhu Mythos is a happy coupling here, I think because the flamboyance of the former and the cosmic horror/cosmic wonder of the latter are so well balanced, no easy feat of tonal blending. We get outlaws and merchants jaunting about the solar system, and a swampy Venus with sunstone mines and pseudoroaches, and a hint at political unrest in the riots from which Black Alice escapes. Neatly incorporated into these operatic tropes are Lovecraftian elements like gillies (gotta be Deep Ones, right?) and Mi-Go. [RE: I’m torn between gillies as Deep Ones and gillies as Golden Age SF Venusians. Both would fit.] An especially neat detail is that most of the ships are named after famous Earth women, which means that in this milieu Lavinia Whateley has earned her rightful place in history (and infamy?) as the mother of Yog-Sothoth’s Dunwich twins.

As befits the center of the story, Vinnie spans both sub-genres. She’s a pirate ship par excellence, capable not only of overcoming all prey but also of getting rid of the evidence by the elegant expedient of devouring it, to the last screw or scrap of murdered corpse. And she’s a showy alien, born from the atmospheric tumult of Uranus, huge and dangerously voracious, yet in the hands of canny spacers, the ultimate pack mule, war horse and even pet.

But, oh yeah, how the spacers underestimate her and her kind. Vinnie is weird beyond their comprehension, and as Black Alice learns, she’s only docile, only obedient, because tormenting mechanical interfaces force her to be so. Black Alice imagines that Vinnie is fond of her human handlers, the captain and chief engineers. She interprets the way Vinnie furls her vanes at their pats as affection, but maybe that furling is as much a flinch as the reaction of captive brains to light. Vinnie has a mind – or many mind-nodes – of her own, and it’s a much more sophisticated brain than she’s given credit for. She can be trained? She’s about as smart, maybe, as a monkey?

It’s Lovecraft who could appreciate the inhuman vastness of Vinnie’s intelligence and her drive toward the Big Empty, the Out as she puts it.

And Black Alice, too. Of all the pirate crew, it’s she who loves Vinnie. As far as we’re shown, the others either outright exploit her or view her as a biomechanical problem. Black Alice wants to talk to Vinnie, not just give her orders. She avoids treading on her eyes or coming down hard on her inflamed flesh. She perceives Vinnie’s response to the “governor” as pain and the “governor” itself as the tool of a slave master.

I’m afraid Black Alice has some acquaintance with slave masters. In the absolute power she wields over subordinates, Captain Song is one. Even so, Black Alice prefers the captain to her former employers in the Venusian mines, as we can infer from her implied involvement in the Venusian riots of ’32. Riots to gain what? Fair treatment? Freedom itself?

No wonder Black Alice sympathizes with Vinnie, and vice versa as it turns out. After Black Alice learns her fears about the disembodied (enslaved?) brains are true, we see Vinnie’s first response to her, the gift of water. Junior engineer and ship have something deep in common: Both are trapped, and both despise the state, for themselves and others.

In Lovecraft we’ve seen characters who find personal freedom by accepting their own alienation from the human norm. I’m thinking of the Outsider, of the “Innsmouth” narrator, of Richard Pickman. Black Alice goes a step further by accepting an alienation away from her humanity, an assimilation into Vinnie that is no obliteration of her own identity, for she’s still Alice afterwards, companion, not captive. Many more Lovecraft characters taste the terrible ecstasy of trips beyond, into the Big-Not-So-Empty, into the Out. Black Alice goes a step further by reading through Vinnie the “whole great naked wonder of space.” She shows no fear. She tells herself not to grieve.

And why not? She and Vinnie, they are going somewhere, leaving the spacers left behind to shiver over tales of the “lost” Lavinia Whateley.

Next week, we’ll cover super-prolific chemist/mathematician/pulp writer John Glasby’s “Drawn from Life.” You can find it in the Cthulhu Megapack, among other sources.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” is now available from Macmillan’s Tor.com imprint. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.