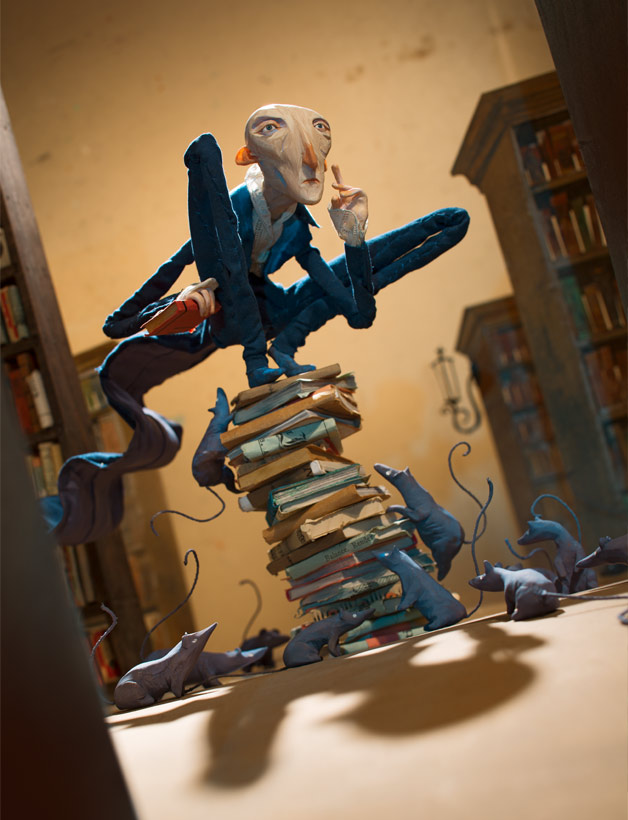

Welcome to the Library of Lost Things, where the shelves are stuffed with books that have fallen through the cracks—from volumes of lovelorn teenage poetry to famous works of literature long destroyed or lost. They’re all here, pulled from history and watched over by the Librarian, curated by the Collectors, nibbled on by the rats. Filed away, never to be read. At least, until Thomas, the boy with the secret, comes to the Library.

The Librarian turned his eyes upon me, reversed the single sheet of paper once, then neatly back again.

“An excellent candidate,” he said.

And:

“Thomas Hardy. An apropos name. We have one of his, you know? No relation, I assume?”

And:

“‘Favourite grammatical form: passive voice.’” He looked me up and down, pinprick eyes narrowed, and licked his dry bottom lip. “Marvellous.”

“Sir?” I said.

The Librarian’s tongue flickered. “So wonderfully uninterested. Most boys, well they come here with their nasty adverbs and their present tense, or, God forbid, second person.” When he shuddered his spine cracked like an old hardback opened in one swift, cruel motion. “Quite unsuitable. You on the other hand…”

And, after some deliberation:

“Very well. The job is yours, young Thomas.”

“Tom,” I said and swallowed with relief that he hadn’t asked me why I wanted to work for the Library. I’d prepared a response, but I doubted it would impress. The Librarian’s eyes were sharp and astute, shadowed in the hollows beneath a foxed brow. He would have picked apart my half-truths, separating non-fiction from fiction and, suspicious, sniffed around the superlative adjectives.

“Come along.” He unfolded his eight-foot frame from the armchair. A stick insect stretching. He led me out of his office, down a long hall which echoed our footsteps, and to a set of ornate double doors. “Through here,” he said, “is the main hall of the Library. You must always treat this place with the utmost respect. We serve a greater good. Stay long and you will know this.”

He guided me through the doors. On the other side, bookshelves reached the horizon.

The Librarian bent close to my ear. He reeked like damp second-hand bookshops, or comic books left to moulder in the bottom of a wardrobe. “How would you describe it, Tom?”

I was still being tested. The interview was not truly over. Perhaps it never would be.

I looked from one behemoth shelf to the next: it was a graveyard of spines, leather, paper, string, the wormed carcasses of all those books, buried next to each other one after another into the dark. The feeling of disintegrated sentences hung in the air, a deadness of language, like a word abandoned mid-syllable.

“It’s impressive,” I said.

“Impressive.” The Librarian outstretched his arms to the expectant hall. “It takes you three syllables to encompass all this?”

I had been memorizing Roget’s 1911. “Large,” I said.

He chuckled. “Better to be faced with an eternity of literature and render it down to one uttered word, one brief sound. ‘Large’—I think you’ll be perfect.”

From beneath a shelf of peeling grimoires, scratchy muttered sounds could be heard. At first I interpreted them as squeaks, then realized instead that they were voices. Words, I realized. “Stripling! Gangrel! Pilgarlic!” A scurry of grey tiny shapes crossed our path and disappeared among the nearest bookshelf.

“Ignore the rats,” the Librarian said. “So bothersome. I try to keep them away from the books, but they over-run the place. They have a particular taste for the folios. I suppose it’s only natural they’ve picked up some words. But such bothersome words.” He licked a spindly forefinger and thumbed his lapel as if he could turn the page of his suit. “To work then, my unremarkable boy.”

He led me through the stacks, past row upon row of books. Some were bound in leather, some gaudy, some decrepit, some little more than stapled paper, and some emanating a faint electric glow. Skittering around in the shadows, the rats could be heard in our wake: “Jackanape! Welkin!”

“Voila!” said the Librarian. “The Index.”

Like a still pool in a forest, the library had given way to clear empty space containing a circle of doors, freestanding and unsupported, each unadorned apart from a single round window at head height. Narrow bookcases stood attendant by each, laid out like spokes within the wheel of doors.

“Observe.” The Librarian plucked the first volume waiting on one of the bookcase-spokes. It was gently smoking; the Librarian carefully patted out its glowing embers. He inspected both of its covers. “Sonnenfinsternis by Arthur Koestler. You do know German? I’ve been waiting for this one. File this under Wartime Casualties.”

And:

A sandy pile of barely bound papers. “The Visions of Iddo the Seer—fascinating. File under Myriad Apocrypha.”

And:

A sheaf of laser-printed paper. “Untitled Novel About a Boy with No Hands (Incomplete) by S. Berman. That’s one for the Self-Doubt section—half a novel deleted in a crisis of confidence, if I’m not mistaken.” He coughed. No, it was a laugh. “I’m never mistaken.”

And:

A threadbare exercise book missing one of its staples. “The Collected Works of the Poet Jeremiah Blenkinsop, Aged 13-and-Three-Quarters. Much as I regret that we must collect such ephemeral dross: file under Adolescent Verse. Do I make the task at hand clear? Take the volume, examine its cover, file in the appropriate section.”

I nodded.

“Under no circumstances do you open the book. Is that clear?”

When I was late in responding, he peered at me. “You are not a curious boy are you? I insist on no aspirations, no predilections. Books are not to be read.”

“I haven’t read a word since my GCSEs, sir.”

He smiled. I suppressed a shudder. His teeth were spotted, like the acid foxing on old paper.

In the round window of the door directly behind the Librarian, a face appeared. It was a wide, flat face, that of a rag doll’s, or a scarecrow’s—the look emphasized further by thick stitches that shut his eyes. The door opened to admit the lumpish creature. Behind it, I saw a vista: not the Library stretching away but a courtyard at night. A mound of books burned and the silhouettes of men watched from below scarlet flags. At the sound of a bugle, each figure raised their right arm high in salute.

The Librarian noted how I stared. “1943 Common Era,” he said in a grave tone. “So many books lost forever. We were understaffed—had been since the Great Pandemic.”

The rag-doll creature unloaded an armful of still-smoldering books onto the case before turning back to the door. The Librarian stopped it. “This is a Collector,” he said, then added, squinting at the nametag sewed on his chest, “Gadzooks.”

“Why are his eyes sewn shut?”

The Librarian scowled. “That’s only a metaphor.” He squinted at me. “You know…symbolic? Not real?” He sighed and bent an arm around my shoulder. “Gadzooks, this is Thomas Hardy. Passive voice, mind you. He’s our new Indexer.”

Gadzooks bowed his head.

“I trust you’ll show him the ropes,” said the Librarian, “and then to his chambers at the end of the day.” He picked up the next book on the shelf. “Misguided Pornography,” he said, then placed it into my hands and shuffled away.

So:

I worked, for an indeterminate number of hours, filing away the books as they were deposited on the stands for my inspection. I saw many more Collectors, barging in and out of their respective doors, carrying armfuls of books; through the frames, I caught glimpses of a multitude of places—a sun-baked Jerusalem, a Scottish highland under water, the underwear-strewn floor of a teenager’s bedroom. 1943 remained where it was even as the others changed; clearly there was much work to be done there. Gadzooks lumbered around gloomily beside me, pointing in the right direction for each department: “Censored Tracts? By the fountain. Suicide? Fourth on your left. Hard Drive Failure? Up the ladders by Rejected First Novels.” His gentle voice belied his maimed face.

Occasionally on my journeys I would spy the rats. One might dash close and spit out a forgotten word at me—“Nidgery! Borborygmus!”—then skitter away back beneath the stacks. Gadzooks grunted and chased them away. “They seem to like you,” he said.

And then:

The day closed, Collectors unloaded their last piles and vanished. All but Gadzooks, who gestured for me to follow him. I did so, because I was a curious boy, and let him lead me into the deep warren of the Library. We arrived at a rickety spiral staircase at the back of Reformation Sermons. The small room at the top was drafty and sparsely furnished, nothing much more than an unmade bed and a little writing table.

“Your room,” said Gadzooks.

I thanked him, expecting him to leave. Instead he hovered in the doorway, wringing his massive and scarred hands.

“Yes?” I asked.

“Sometimes at night, we—well, I wondered if you might like to come…to a party?”

And then:

A trio of Collectors recited couplets from Love’s Labour’s Won, regaling each other with smutty double entendres. In another corner, a gaggle of Collectors pored over Byron’s diaries, pausing frequently to ooh and ahh. Another group gathered in armchairs, pouring absinthe over sugar cubes into their glasses, and repeating lines to each other from Rimbaud’s La Chasse Spirituelle. “Welcome to the Speakeasy.” Gadzooks moved with a bit of mirth.

He led me to the bar, introducing me to those we passed on the way, a series of names—Tango, Philtrum, Esperanza, Pushkin—that I immediately failed to correctly attribute to their proper owners. “This is Tom, the new Indexer,” he said, and they all earnestly shook my hand and recited couplets for me by way of introduction.

“Whiskey,” said Gadzooks at the bar. “You do drink whiskey?”

I felt bold. “Naturally.” A glass was pressed into my hand.

Perched on a bar stool atop a table, there was another boy, who looked older than me because of his long silvery hair. He played an elegant tune on the violin. “From the Library of Music across the Silent Canyon.” Gadzooks caught me looking, and perhaps mistook the expression on my face. “They sneak across when the Librarian isn’t looking. That tune he’s playing—Mozart and Salieri’s Per la Ricuperata Salute di Ophelia. One of their prize possessions.” But I wasn’t thinking of a boy from the halls of lost music; instead, I was remembering a boy from a place far more ordinary and humdrum, though his fingers were no less nimble on the strings.

Still—he was a long way away, and I was here, in the Library, and that was the price I had paid.

They refilled my glass a second, then a third time, and I gladly accepted.

The door burst open and two Collectors entered, flanking a man covered entirely by a threadbare blanket. The door safely closed behind him, he threw off his covering, and spread his arms; he was greeted with a cheer. At first glance he appeared emaciated, almost consumptive, resembling a child’s pipe-cleaner puppet, but he had a flamboyant assertiveness that belied the wispiness of his physical presence. “Ladies and gentlethings, I am here! Quite enough of the sad songs, don’t you think?”

The musician switched to a guitar and launched into a rendition of David Bowie’s “Jean Genie,” though this version of the lyrics weren’t those Tom remembered; a lost version, he supposed, like everything else here. The song seemed to prompt a sea-change in the party; a Collector with beautiful silver stitching climbed up beside him and swayed her hips, the bartender began acrobatically tossing bottles, the patrons starting to turn around the dancefloor with a newly giddy energy.

“That’s more like it,” said the man, sauntering to the bar. “And, why hello to you! Gadzooks, who might this handsome fellow be?”

“Tom—the new Indexer,” said Gadzooks.

Although I had known the man was referring to me, I feigned surprised.

“A shame—one must never fall for an Indexer; the lamps are lit, but there’s never anyone home.” The man seized a glass from the bar, and tapped me on the nose. “Lovely you might be…but I require a tryst to possess a modicum of intelligence. What comes out of a mouth is just as vital as what goes in.” He gave me a lingering look and then left for the swell of partiers.

“Who’s he?”

Gadzooks looked at me as if I’d spat on his paws. “Jean Genet. We recovered the original Notre Dame des Fleurs. The Librarian has no idea.”

Genet perched himself atop a suitcase in the centre of the room, thumbing theatrically through a sheaf of papers in his hand. “Shall I read?” he called out to the crowd, who cheered and held their drinks aloft. “Very well, very well. ‘I wanted to swallow myself by opening my mouth very wide and turning it over my head…’ Oh, this is one of my favourite bits! I remembered it word for word—got this one just right!”

Gadzooks handed me another glass. “That’s Hemingway’s suitcase that he’s standing on,” he said, with great import.

When I did not react with awe, he sighed and abandoned me.

I didn’t remain alone for long.

Genet plucked at my shirt-sleeve. “Remarkably, I find it easier as the night wears on to ignore your lack of discursive faculties. Animals rut, and they cannot reason.”

I sipped from my glass, holding it as a meagre barricade between myself and him. I had been with men. I preferred it. But never with a Genet.

He summoned two tall conical glasses from the barman, and placed a slotted spoon across each one, on which he placed a sugar cube. His fingers—contrary to his otherwise louche presence—were long and nimble, executing his actions with quiet delicacy. I found the practiced nature of his preparations reassuring.

Absinthe trickled over the cube, dissolving the sugar, and pooling in the bottom of the glass. Genet interlinked his arm through mine, bending it back around to reach his mouth. “Thank goodness you’re not Rimbaud,” he said before taking a gulp. I sipped and coughed. He laughed. His warm breath traced across my cheek before he kissed me hard. He drank again, and determined, this time, I matched him sip for sip. It lit an emerald fire in my belly.

There were boisterous shouts rippling around the Speakeasy—Genet wheeled around, discarding his empty glass. “What’s that? You want me to go on a night run?”

I swayed on my stool. “What’s a night run?” Was it the longest sentence I had said all day? It felt marvelous.

“Wait and see,” said Genet. I caught a glimpse of Gadzooks across the room. He shook his head, and I wondered if the gesture indicated disappointment or a warning. No matter—Genet took my hand and pulled me up. “I’m hearing…‘The Ocean to Cynthia’ by Walter Raleigh? Any other offers?”

Calls sounded from around the room.

“The Romance of the Devil’s Fart!” “Inventio Fortunata!” “A Time for George Stavros!” “The Poor Man and the Lady!”

Genet gestured as if he had tasted a bad oyster. “Boring!”

“Plath’s Double Exposure!”

Genet grinned. “Excellent. Come along, my handsome witling!”

And then:

The overhead gas lamps were extinguished, but a kind of luminescence, much the same lustre as moonlight, emanated from the stitching of the oldest books on the shelves like silvery skeletons. I crouched low.

Genet swaggered ahead of me. I half expected him to burst into song, or start skipping.

At the Index firelight still burned in one door window, casting a lone spot of colour across the flagstones. Genet stood and looked through, waiting for me to catch up. “1943,” he said. “I escaped from one hell into another.”

He spun on his heel. “Just through that door and a few streets away there is a room above a tavern. And in that room is a bed with springs that sing as you fuck. Would you like to discover conjugating?”

A rat scurried. I jumped, startled, which he mistook for virginal anxieties.

Genet laughed. “Relax. We must forge a path to Plath.” He led me away from the ring of doors. He seemed to have a knack for moving without eliciting noise; I did not share it. Each footfall of my own rang back at me from the shelves. I fell behind. Genet had vanished, leaving lazy spirals of disturbed dust in the air, and I was on my own.

I anticipated he would be thumbing through the Suicide section, but I arrived and found it solemn. Rather than being alphabetized, here the shelves were organized by methods of dispatch. Most works were incomplete. I traced my finger along the shelves, moving from gas oven to hanging, then finally to razorblade. I squatted, tilted my head to read the spines.

And there it was:

The Sum of All Our Tales. Barnabus Hardy. A single slim volume, it seemed insignificant in the vastness of the Library. I pulled it carefully from the shelf, and ran my fingers over the plain cover. The type was raised; my skin prickled. To hold the book in my hands had been worth the exhausting pretenses of the day.

A tiny voice spoke in the dark, inches from my ear. “Swivet.”

I nearly fainted.

I envisioned the Librarian leaning down from the ceiling, his hands armed with a needle and cord with which to sew my eyes shut.

The rat sat bolt upright on the fourth shelf, grooming its snout. “Zamzodden.”

I looked around before uttering “Rumblegumption.” The sheer delight of multiple syllables, held dammed up inside me all day, burst onto my tongue. I added another for good measure. “Falstaffian.”

It paused and cocked its head. Shiny black eyes stared at me. “Anopisthograph.”

I thought for a second. “Sardoodledom.”

The rat twitched its nose and long whiskers and dashed away, throwing back over its scaly fine tail a disgruntled, “Ninnyhammer.” It dislodged a book, which fell with a ponderous thud.

“Well now, my handsome library boy. This is a surprise.” Genet was leaning casually against Shotgun/A-G, watching me. He stepped close to me. In the moonlight, it was almost possible to describe his gaunt face as handsome. “I was injurious in my dismissal of your mind. Hiding such an”—he reached out and grabbed at the crotch of my trousers—“impressive vocabulary would be grounds for”—he squeezed and I gasped (truth be told, I was hard, rigid, tumescent then, both by the wickedness of the man and my discovery)—“termination.”

I stepped back and he released me. His scuffed shoe nudged the fallen book. Double Exposure. “Of course,” I said. “We should go back.”

He tsked. “Say it right.”

I sighed. “It would be auspicious for us to return to the Speakeasy before our mischief is discovered by a certain overseer.” Somewhere within me a door opened.

The Librarian found me on the morning of my second day’s employment hungover and only a few breaths short of whimpering at every book deposited by the Collectors for me to index.

“How’s our young man doing?” he said, unfolding his papery frame from between the stacks.

Behind him, Gadzooks mumbled something. He had barely glanced at me beyond the necessary since the night before, when Genet and I had burst into the Speakeasy out of breath and disheveled and sweaty.

“Fine,” I said, enunciating the single syllable with care.

“Tremendous, tremendous,” he said, rubbing his endpapers together. “The Index is looking pleasingly sparse. Fine job, fine job.” He paused, mid-flow, and looked around, wrinkling his nose. “Hmmm.”

And:

“Hmmmmm.”

I rubbed my bleary eyes. “What’s wrong?”

Gadzooks looked away.

The Librarian took a deep breath which expanded his torso like an accordion. “Something smells amiss,” he said. “No. Something smells…missing.”

I risked a glance over his shoulder, to where the slim pink spine of Double Exposure sat on the shelf.

The Librarian sniffed again. “Most incomprehensible.” He departed, dragging his long coat on the ground, which rather than wiping them bare instead lined the flagstones with dust in his wake.

I fretted all the day. Shelving volume after volume of lost books, I slipped more than a few times on the cold brass ladders. Behind texts, the rats devoured the deracinated and the archaic. Gadzooks labored next to me, but he still avoided conversation.

That night he did not invite me back to the Speakeasy. I didn’t mind: I had other things to occupy my time. Before he had been smuggled back to 1943, Genet had pressed the worn copy of Our Lady of the Flowers into my arms, suggesting that it might make good bedtime reading, and departing with a lascivious wink. (Thinking on it later, his precise words had been, “Take this and think of me in bed,” which I supposed wasn’t quite the same thing.)

And so it was for a week or so. The Librarian would appear unbidden and unnoticed, sniffing the air before vanishing, leaving me to dreary tasks—filing the assembled works of a seven-volume fantasy epic into Doubt, box after box stuffed into Teenage Diaries, navigating the complex organization of Pantos/Variations/Peter Pan.

Gadzooks had been correct about the rats’ fondness for me; they would appear amongst whatever shelf I was tending. “Anopisthograph!” said one in particular. I was convinced it was the very same rodent with which I had exchanged words on the night run. “You’ve already had that one,” I said, and shooed it away.

The next day I saw the Librarian sniffing around the display that featured famous luggage—the Library must have had other workers, still unseen, who tended to the glass-enclosed exhibitions of the detritus of authors—and with that long finger tapped by Hemingway’s suitcase. I was thankful that—for tonight at least—Genet’s manuscript was not hidden within as it usually was, with such fragrant prose that the Librarian could not have failed to scent its presence.

Yet, for all his strange behavior, the Librarian didn’t seem to suspect I possessed an intellect or a libido.

Eventually Gadzooks thawed, and reappeared at my bedroom door. “Would you like to—y’know…?”

At the Speakeasy, Genet regaled the crowd from atop the suitcase. (I wondered what had Hemingway done to Genet to deserve such roughshod disregard for his possessions, and eventually asked him; he said only “The man is famous for writing about a fish. Not a whale but a fish.”) Genet greeted me loudly. “Witling! I don’t suppose you have my book on you? I’ve drunk enough to chase away the memory of what I wrote ages ago. That I can remember my own name is a wonder.”

He pirouetted drunkenly, and toppled over. He chuckled. “Perhaps I shall just be Jean tonight and let Genet stay on the shelf.”

I helped him to the bar. I arranged two glasses, placed spoons over them, and a sugar cube atop each. Genet watched my hands as I poured the absinthe over it.

“Why do you leave it here?” I said.

“It? Pronouns are the weakest of words. Even an adverb has more panache.”

I leaned into him. He thought I meant to kiss him and I moved at the last moment so my lips touched his ear. “Your book,” I whispered into it, and felt Genet press vigorously against me; after all, what words could be more seductive to a writer? “They smuggle you in, they smuggle you out—couldn’t you take it with you?”

Genet held my face in his hands and blinked a while. “A first draft—a mere masturbatory fantasy. It belongs right here, one more lost book. It’s a dirty rag for my spent fantasies, written in the throes. What was published is superior.” He frowned. “At least, that’s what the Collectors say. I’ve only sold…” He let go of me and began to count on his fingers but quickly lost his way. “Well, not many, but they tell me that one day—”

I kissed him. Our teeth clicked and thankfully parted. We had yet to even drink the sugared absinthe but I found his mouth so pleasing that I did not notice someone tugging at the cuff of my trousers.

No, not someone. A rising wave of noise broke the familiar chatter. The minstrel faltered in his song; the assembled revelers bloomed into panic. The single rat at my feet let go of the fabric and leapt for my knee, claws digging through my trousers into the skin. “Anopisthograph. Anopisthograph!” and then at the doors the noise crescendoed with a tumult of panicked rats spilling through and across the floor.

Genet cursed. I shouted, “The Librarian!”

And:

“Run!”

And:

We dashed, and it was hard not to laugh with how Genet smiled as we escaped. I pulled him towards the Index; he pulled me towards the staircase; in the tension between the two we spun in each other’s arms as if we were dancing. In the end, I did not deny him another night spent in my bed. I shut the door fast, almost crushing the rat that scampered in and took refuge in my writing desk.

“Ow,” Genet said as we collapsed onto the mattress. “How can you sleep? What is in this? Horsehair?” He wet my lips. “Have you ever eaten cheval?” He groped me. “It’s an acquired taste.”

Authors were indeed.

I nibbled on the sweet rolls they fed us. I had pocketed an extra one for Gadzooks.

“The last Indexer would give me his meals,” Gadzooks said as he chewed. “He never came to the Speakeasy. He wasted away in his room.”

“Lost in a book?” I said.

“Oh, no. He didn’t dare read. I think that’s why he faded to nothing. Every time he spoke he lost the words in his head.” Gadzooks rapped on his misshapen skull. “If you don’t replace that with something…even feelings, then you stop.”

I had so many words in my head but I wasn’t sure if there would be enough feelings if I lost my vocabulary.

A rat scurried into the middle of the Index.

“Anopisthograph.”

And then:

“Thomas Hardy,” said the Librarian. His fingers traced down my cheek and neck, and far from the brittle dryness I had imagined, they felt sharp, as if they might leave a trail of papercuts on my skin. “Quite fascinating. Such a faultless resume should have been enough to make me doubt. Clever boy…I was lulled by the passive voice. I should have checked your references.”

The rat turned slowly, almost apologetically, and backed away beneath the stacks. I sighed.

“Indeed,” I said. “That would have been prudent of you. Judicious. Shrewd. Discerning, even.”

The Librarian winced.

Gadzooks attempted to fade away into the shelves. “Ah-ah-ah,” said the Librarian. He beckoned Gadzooks closer with a crooked finger. “Surreptitious sneaking—I’m afraid I cannot allow that.”

With one hand the Librarian covered my face. I feared he meant to smother me; his skin against my nose smelt of spilt ink, the emaciated palm against my mouth made me choke with its taste of glue.

Then I heard Gadzooks scream.

The Librarian released me. All that remained of my Collector friend was a large hessian sack and some old wooden toys. A yo-yo stopped spinning, its thread a last umbilical cord.

“Don’t think of it as murder,” said the Librarian. “Think of it as a metaphor for murder.”

I swallowed.

“The old beak warned me. Something missing. Boys before you sneaked into Unwarranted Adventures or Illegal Pornography. But you went there.” He gestured at the door. Neither of us needed to say aloud the section.

“What am I to do with you?” He plucked from his coat pocket a book that made my heart sink. “And more importantly, what am I to do with this, found in your mattress.” He inspected the spine. “The Sum of All Our Tales, by Barnabus Hardy. Father? Grandsire? Brother?” He leered. “Lover?”

“Father.”

“Pity,” the Librarian said. “You must have been so young. The age when you were warned about razorblades in Halloween candy—not the bathtub.”

I stiffened.

“No note. Just his final manuscript. Did the literary world mourn his loss?”

“Stop.”

The Librarian shut the book hard enough that his clothes rippled. “By all means. But tell me, young Hardy, have you ever heard the word ‘deaccession.’ Not so common any more, which is a shame.” He opened the grate of the nearest gas lamp. I screamed at him to cease, to desist, but still he poked one corner of my father’s only book into the flame.

He dropped the papers curling into ash as the fire spread.

“A lesson, a dear lesson in realizing what a lost book is,” he said.

The Librarian’s immense arm pressed me back, anticipating me wrestling free, though I didn’t know what I would do even if I could escape his grasp—perhaps throw myself on the fire in hopes of extinguishing it, rescuing the scorched remnants of the manuscript from the ashes? But it would be futile: it does not take long for poetry to burn. Verses are highly flammable—it’s because they were dear fuel in someone’s imagination.

“Consider that a written warning—obviously it cannot be filed away, but…well, I am a practical man. With the elder Hardy’s esprit in ashes perhaps you will no longer want to open a book again.” The Librarian straightened his bow-tie. “You may take the rest of the day off. If I find you at the Index in the morning, I will know your decision to stay with us. At a reduction in salary.”

Perhaps my gaze was too wet with tears to set his retreating backside ablaze.

I trudged to my room. The Librarian’s search had torn apart bed and desk. I sat down on the floor and wrapped my arms around my knees.

Something climbed up my back and to my ear. “Empressement.”

I stroked the rat with two fingers. It chirped and then nipped gently at my earlobe. “Frantling.” It leapt to the ground and ran towards the door, stopped and looked over its shoulder at me and squeaked. “Usative.”

I followed it through the maze of the Library. The lighting where we tread was dimmer. I had not been everywhere. Some subjects were unknown to me. Down one path I saw a familiar figure reclining on the penultimate shelf devoid of books. The rat scampered away as Genet peered up at me.

“Sometimes I do not go back,” he said, looking chagrinned. He handed me the book his head had been resting on. A Scheme for a New Alphabet and a Reformed Mode of Spelling by Benjamin Franklin. “How he loved whores. Once they brought him to the Speakeasy and all he wanted to do was steal a boy’s glasses and find the door leading to ancient Lesbos.”

Genet stretched, a gesture that was part exercise and part pretense to embrace me suddenly. “I doubt more than a handful of authors end up in Wasted Graphemes so it is safe here.” He touched my face, my cheeks. “Ahh, but you recently had a terrible encounter with the wicked regent, I see.”

I told him of my father, of his poetry. It had been years since I spoke of being away at school when they found his body, of life at the homes of distant relatives who could not look at me without seeing a debt to family they wanted little part of. My last name was all I had of my father’s until I learned of the Library.

“You must feel his loss keenly.”

I shrugged. “My father is a long-closed chapter.”

“Ah, I see. The book, then—you mourn the loss of the book.”

“Something like that.”

“We shall toast to both the man and his book at the Speakeasy tonight,” Genet said, laying a hand on my shoulder.

I rested my cheek against Genet’s fingers. “Actually—I had another thought. If you don’t mind.”

And finally:

1943 smelt of fire and paper. Feet stamped in unison, close by; voices intoned, “Heil Hitler!”; the books of Germany burnt in the courtyard, a gout of gluttonous smoke bearing their words into a sky already thick with many volumes. I backed away from the bonfire as fast as I could, pushing through the crowds that railed against the soldiers, shouldering my way through and away. Away from the crowd, away from the noise. Ducking into an alleyway, I paused to breathe, heaving against the damp wall.

One hand was in Genet’s as I pulled him along behind me; the other clutched tight to the worn leather handle of Hemingway’s suitcase. Several street corners away, I pulled Genet into an alleyway. “You said you had a room near here—the room above the tavern, where the bed-springs sing?”

He pressed against me, mouth close to my ear. “How forward of you—I like it.”

He led me a few streets further, arriving at a narrow doorway in the shadow of rotting tenements, the tavern windows the only warm thing in sight. He fumbled with a key, whilst I wrapped my arms tight around myself and shivered. Away from the book-burning, the city was freezing. Eventually, Genet persuaded the door to open, and he led me up rickety stairs to a room reminiscent of my chambers at the Library: sparse, furnished with a bed and a writing table. The greying sheets were balled on a threadbare mattress, and the table was strewn with papers. The floorboards creaked and wobbled beneath our feet.

There was a murine flicker by the doorway, and a scaly tail darted between my feet. A whispered word floated back in its wake. “Anopisthograph!”

I sat on the bed, still shivering. Genet watched the rat depart and closed the door. The sound of the key in the lock released me; the tension of weeks in the Library, fumbling around under the Librarian’s watchful eye, drained away. I sank back.

Genet lay down beside me, his skin warm against mine. He smelt of absinthe and book dust; I had the urge to bury my face in his chest, but my bone-weary limbs wouldn’t co-operate.

“Will you read to me?” I said.

He arched an eyebrow, and nuzzled against my shoulder. “My handsome witling—foreplay, is it?”

“This isn’t foreplay.”

“I have nothing to—”

“The suitcase.”

The bed-springs sang as he arose; I heard the grate of the lock opening, and the rustle of papers, then Genet returned to me with the contents of the suitcase in his hands: the first manuscript of Our Lady of the Flowers, where I had returned it when I had finished.

Genet smiled faintly. “My slack-handed first draft—but if you insist…” He cleared his throat, and raised the first page to his eyes. “‘Wiedmann appeared before you in the five o’clock edition,’” he began.

“No,” I said. “Turn it over.”

He did as I asked, squinting at the fresh scrawl that coated the reverse of his pages.

“Sorry about my handwriting,” I said. There had not been light in my Library chambers, or much space with which to work. My letters had been shrunk to the smallest I could manage to cram in everything I needed to write on the pale underside of Genet’s own pages.

Genet sat up on the bed, crossed his legs, looked from the page, to me, and to the page again. He cleared his throat theatrically. “‘The Sum of All Our Tales, by Barnabus Hardy’,” he began.

“The Library of Lost Things” copyright © 2017 by Matthew Bright

Art copyright © 2017 by Red Nose Studio

A terrific story! Well done, Matt. And I would not be surprised if we venture into the Library once more…

What a fun story. I loved it!

I’d like to go back to the Library. Good odd little story

Lexicographic facility.

Polysyllabic erotica.

Erudite presumptuousness.

I am extremely pleased with this fantastically dreary tale of lost literatures: so much so, that I am at a loss for words, and had to use some of my less frequently-used descriptors that just happened to be laying around in the “lost & found” area of my Broca’s region.

Great job, and the rats are a splendid aspect of The Library. Kudos.

What did they pour? If even Tor can make this mistake…

I looked up “anopisthograph” and wondered until the very last paragraph why a manuscript with writing on only one side of each page was important.

Well played.

I was immersed in this world from start to finish. It was descriptive and enchanting. I would LOVE to read more of your work. I could see this as a novel that I would be honored to read.

Brilliant. And so many new (to me) words. (I love “murine” amongst others).

I can’t help but wonder, given that in-progress drafts are saved in the library, where the line is drawn. A typical draft goes through literally thousands of iterations. Are there literally thousands of versions of each draft work in the library?

8. When was an in-progress draft mentioned? I thought it was all works that had been either physically lost (as in the works lost in 1943) or works where a conscious decision was made to not make them (as in the Salieri-Mozart collab).

PS: spotted a typo. The word is “Borborygmus” not “Boyborygmus” as is written above.

(Feel free to delete this comment after correcting.)

@10: Corrected–thanks!

Great story. Lovely prose. Only one criticism. Does this paragraph:

The musician switched to a guitar and launched into a rendition of David Bowie’s “Jean Genie,” though this version of the lyrics weren’t those Tom remembered; a lost version, he supposed, like everything else here. The song seemed to prompt a sea-change in the party; a Collector with beautiful silver stitching climbed up beside him and swayed her hips, the bartender began acrobatically tossing bottles, the patrons starting to turn around the dancefloor with a newly giddy energy.

–switch to 3rd Person POV for a reason? Or is it an error? Both preceding and following paragraphs are in 1st Person POV.

I enjoyed the story, but … In addition to “borborygmus” and “poured over,” as already mentioned, “jackanapes” is the singular form. Also, the combination of British spelling and American punctuation is a little jarring.

Someone please make this into a film. Please. Soon. Please and thank you.

This was a lovely and fun story. I especially loved the description of the librarian.

This was so good-weird. It felt like one of those dreams where things aren’t exactly adding up and you kind of realize you’re dreaming but you don’t want to wake because it’s so interesting.

I would love this as a novel – I have so many questions!

Amazing. Delicious. Enchanting. Delightful. I want to frame it so that I can read it and read it over again. What a wonderful film this would make…with Terry Gilliam directing, of course. Bravo. <3

Absolutely brilliant. Well done!