In Which Ilúvatar, After Creating the World, Presents Specific-Yet-Vague Plans for the Future, and Melkor Becomes a Rebel Without Probable Cause

The Ainulindalë—“the Music of the Ainur” in Elvish—is a kind of prelude story to The Silmarillion proper. It’s the literal beginning to the legendarium, and though it’s only a few pages long, there’s a lot packed in there! For an author famous for long passages and rich detail, J.R.R. Tolkien does a surprisingly good job at concision with his ancient history. With so much foundational material to grasp—and much of it important for future chapters—I am therefore only going to talk about the Ainulindalë in this article.

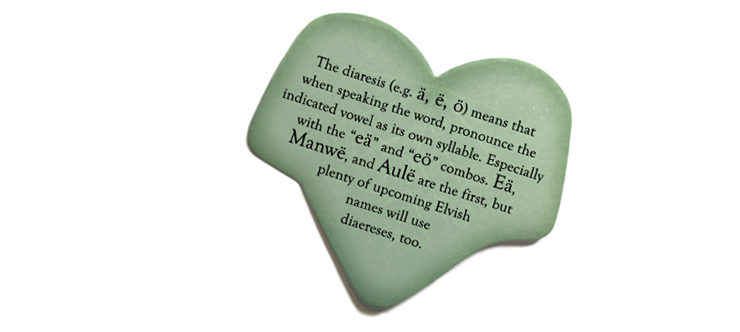

To start off, if you can pronounce Ainulindalë (eye-noo-LINN-da-lay), you’re already in great shape…

Dramatis personæ of note:

- Ilúvatar – the One, the creator of all

- Melkor – an Ainu, the most gifted (and rebellious) of them all

- Ulmo – an Ainu who sure likes water

- Manwë – an Ainu, air enthusiast

- Aulë – an Ainu, into earth and making things

Ainulindalë

Things get underway in a very Genesis-like fashion; in fact, the earlier the chapter, the more biblical everything sounds. In the very first sentence, we meet the legendarium’s one and only all-powerful god, Eru, the One. But Eru is just how he signs his name. He’ll actually go by Ilúvatar (ill-OOH-vah-tar) among the Elves, and therefore us. But I’m getting ahead of myself, as there are no Elves yet. And I say “he” because the narrator uses such pronouns, but gender itself seems to be a trait of the world—and there is no world yet. You’ll see.

Presumably because no one else existing is rather dull, Ilúvatar makes the Ainur (EYE-noor) from his very thought. The Ainur (singular, Ainu) are entities reminiscent of both archangels and polytheistic deities, as they are divine beings of enormous power who will assist Ilúvatar in the creation of the universe and help oversee its future. We don’t know how many of them there are—hundreds, millions, who can say?—but by the end of this section we will be concerned only with a dozen of them. And of those, only a few are even named in the Ainulindalë.

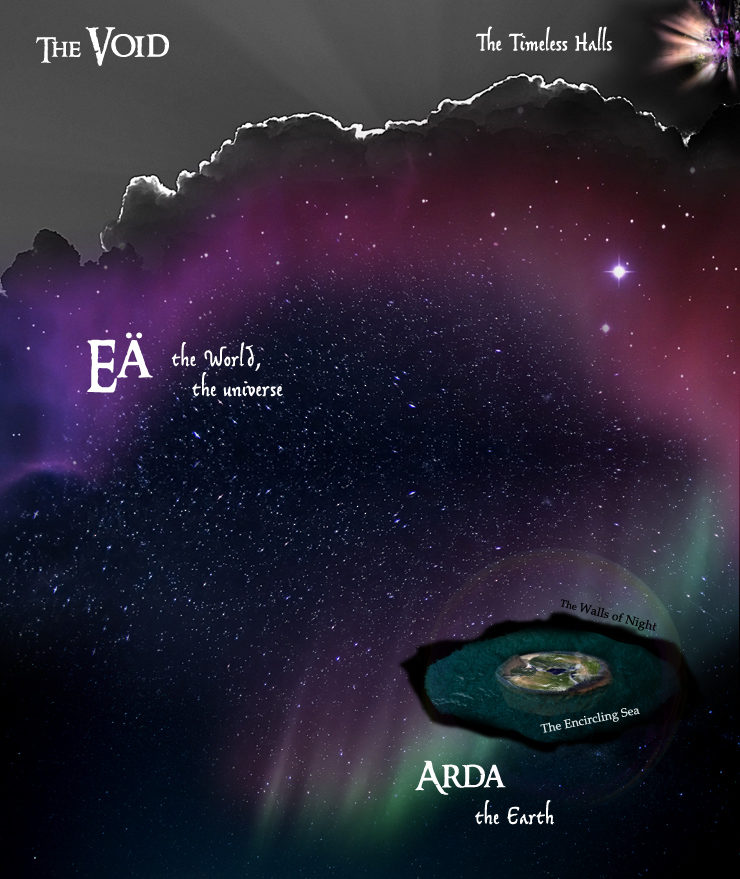

Though there is apparently no familial bond between the Ainur and their maker, I cannot help but see Ilúvatar as something of a godparent, or maybe foster parent, or even benefactor. I hesitate to say father, for reasons I’ll get to shortly. He cares for the Ainur and invests power and trust in them—desiring their company and their artistry for what he’s planning. He lets them dwell with him in the Timeless Halls, which must be some prime real estate indeed, considering there is nothing but a great Void everywhere else.

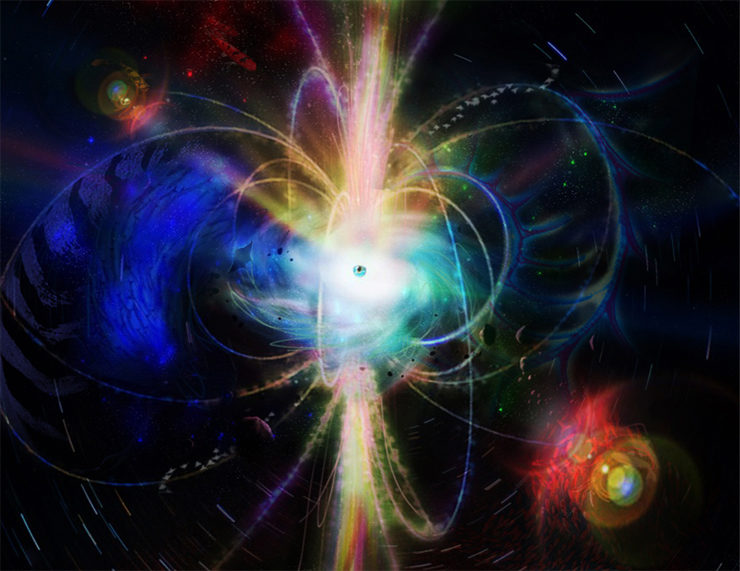

Music as power is a recurring concept in The Silmarillion, especially in creation itself. And though Ilúvatar loves music, he doesn’t do any singing himself. Rather, he is the composer, the muse, and the audience. He gives the Ainur vocal themes to sing, writ not on sheet music but within them, kindled like a “secret fire” by the Flame Imperishable. Think of that as the ultimate cosmic power source. (And yes, it’s the same Secret Fire referenced by a certain wizard on the bridge of Khazad-dûm.) Thus empowered, the Ainur can now “adorn” the musical themes he has given them, and Ilúvatar requests that they sing to him while he listens—if they wish to.

Wait—if?

Well, yes. Possessing the free will to choose—in this particular case, to sing or not to sing—is going to be a huge recurring motif throughout The Silmarillion. And this is no mere illusion of choice, either: sometimes the “wrong” decision is actually made and consequences unfold accordingly. But here we see, from the get-go, that the Ainur do elect to sing the themes that Ilúvatar has given them. They want to. And they find that when they sing, they hear and thereby learn more about each other.

Now, the Music of the Ainur is not some lockstep chorus, but the mother of all jam sessions. Ilúvatar has presented the themes, but he’s left each Ainu to improvise, harmonize, and experiment however they wish, as long as it’s in accordance with those themes. If one Ainu desires a folk rock version of the theme, then soft and melancholic it shall be; if another finds heavy metal truer to their hearts, then darker and graver that same theme shall be. Ilúvatar likes rock either way, is what I’m saying. He wants the Ainur to be individuals, to express themselves, to be artists in the Music. I can’t stress that enough, because those differences are going to take shape in the world to come.

Interestingly, the Ainur are effectively “blind.” But it’s fine, as all of this is playing out in a great Void, where there is nothing but the dwellings of Ilúvatar and the Ainur and their music—and that music spills out into the Void, making it less so. They still perceive each other and Ilúvatar, and can obviously hear as with ears, but they are bodiless, spiritual beings. And time doesn’t really exist yet as we understand it. Heck, the universe itself doesn’t exist yet. But what does exist so far—and the Music of the Ainur—is perfect, flawless, and Ilúvatar seems pleased.

But every great story must have conflict, right?

“Spoiler” Alert: There’s really only one passage that peeks far ahead into the future. Speaking of this great music, we are told:

Never since have the Ainur made any music like to this music, though it has been said that a greater still shall be made before Ilúvatar after the end of days. Then the themes of Ilúvatar shall be played aright, and take Being in the moment of their utterance, for all shall then understand fully his intent in their part, and each shall know the comprehension of each, and Ilúvatar shall give to their thoughts the secret fire, being well pleased.

So, if the themes of Ilúvatar are going to be “played aright,” then I guess that means you know they’re going to go awrong first. Not too spoilery, as spoilers ago, since one paragraph later, we’re introduced to the instigator of all that goes wrong.

Thus do we meet Melkor, one of the Ainu, and kind of a prodigy among them. We are told he has at times gone off into the Void alone in search of the Flame Imperishable, seeking it as if it were some Pac-man Power Pellet floating all by itself for the taking. In going off alone, Melkor has developed some ideas and desires that are not quite in line with those of the other Ainur. He wants to make things of his own, independent from the boss, wanting the Void to not be so void. He is, at the first, impatient. He won’t be the only Ainu to exhibit impatience about creating things—and his impulse to create is not necessarily a bad thing in itself—but he will be the only one to carry it to a terrible conclusion.

Melkor fails to find the Flame Imperishable—because of course it’s with Ilúvatar alone—so he tries to assert his ego in the music itself. He’s a powerful jack-of-all-trades; we are told he has “a share in all the gifts of his brethren.” And though he’s been singing with the others, Melkor now wishes to stand above them. He is the student not content with being the most talented; he also needs to be team captain, prom king, prom queen, and valedictorian. So he begins to deviate in his singing, adding his own selfish thoughts to it. He strays from Ilúvatar’s theme, not because he thinks a face-melting solo will totally impress the others—that would almost be okay, if it was just to make them happier—but because he wishes to increase his own glory. He must upstage, outshine, be acknowledged as greater than the rest. Melkor is the ultimate Me Monster.

He brings discord to the music of the Ainur. It disturbs those around him, making them falter in their own singing, and it grows louder and louder, becoming infectious. Some of his fellow Ainur even start to attune themselves to his deviant melodies like a particularly nasty earworm. It becomes increasingly disruptive as it grows, and like a “raging storm” the discord eventually roars around Ilúvatar’s own throne. It might be tempting to sympathize with Melkor as a nonconformist, to regard him as simply thinking outside the box—but as we’ll see, that’s not really the problem. It’s that Melkor wants to own the box.

Ilúvatar does not scold Melkor for his transgressions yet. He has placed trust in the Ainur, after all, and does not prevent them from doing what they will, even if that means allowing disharmony. Ilúvatar smiles like a patient elder and responds to the discord by initiating a new song, a second theme that swells and increases the power of the whole. And Melkor, spiteful little brat that he is, fights this one, too. He needs to be the best, to be shown as mightier than his creator. The whole thing becomes a war of sound so cacophonous that some of the other Ainur stop altogether, too bothered to continue.

Ilúvatar thus prompts a third theme in the Music, which is especially momentous and foreshadows events to come:

This one was deep and wide and beautiful, but slow and blended with an immeasurable sorrow, from which its beauty chiefly came. The other had now achieved a unity of its own; but it was loud, and vain, and endlessly repeated; and it had little harmony, but rather a clamorous unison as of many trumpets braying upon a few notes.

“Beauty from sorrow” is worth remembering. Though Melkor’s music tries to drown that third theme out, his “most triumphant notes” are actually woven right back into Ilúvatar’s own. But it does seem like Melkor has managed to at least piss Ilúvatar off, though that may be overstating it. By whatever means the Ainur can perceive, Ilúvatar’s face becomes “terrible to behold” and it is clear that he has had enough. He halts the music suddenly, right after an epic crescendo.

Ilúvatar addresses the Ainur now, reminding them who they are—and who he is—and informs them that he will now show them what all their singing has been for. And then, specifically addressing Melkor, he drives home a particular point which will also be well worth remembering in chapters to come:

And thou, Melkor, shalt see that no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined.

Which is to say, “Know that whatever you even think of started with me first. Whatever deviation or evil you make in days to come I will use to enact even better things, things that will blow your mind.” Melkor, like a scolded kid, is shamed but quietly harbors anger. He does not ask forgiveness, he does not repent. He just broods and pouts. He certainly never takes Ilúvatar’s “shall prove but mine instrument” statement to heart. He will only try again and again to exert his own will upon events.

After this, Ilúvatar gives the Ainur the power of sight, and reveals to them a great vision. As if in a huge metaphorical classroom, he flips off the lights, turns on the projector, and plays for them a holy-crap-totally-amazing movie. It’s like watching a film adaptation of their music! The music was not for mere entertainment, as they might have thought, but has provided the blueprints for the universe itself—for the World with a capital “W”—which Ilúvatar will soon make “globed amid the Void.”

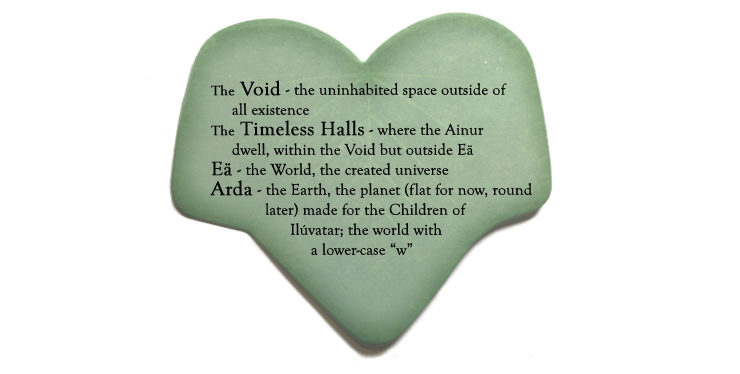

Hmm. Time for a helpful sticky note to keep some terms straight.

Let’s change the metaphor a bit. Like space rebels looking at a holographic schematic of a moon-sized battle station—only way bigger, more lovely, filled with bright and colorful creatures, and intended not for destroying but for designing—the Ainur gaze upon this vision with wonder. They can see now what their thoughts, their artistry, their musical imaginations, will become when the World is made manifest. Ilúvatar has given all the Ainur a hand in creation, though the actual creation hasn’t happened quite yet. He goes on to talk to them, and from his words they inherit the wisdom and foresight that we will henceforth associate with the Ainur—that which makes them godlike in knowledge compared to all other peoples. Through Ilúvatar’s narration over this vision, they even see the future history of the World unfold. This will give them foresight—but it’s not complete, nor fully predetermined; what they’re looking at is still just a hologram, a pre-production film.

Let’s change the metaphor a bit. Like space rebels looking at a holographic schematic of a moon-sized battle station—only way bigger, more lovely, filled with bright and colorful creatures, and intended not for destroying but for designing—the Ainur gaze upon this vision with wonder. They can see now what their thoughts, their artistry, their musical imaginations, will become when the World is made manifest. Ilúvatar has given all the Ainur a hand in creation, though the actual creation hasn’t happened quite yet. He goes on to talk to them, and from his words they inherit the wisdom and foresight that we will henceforth associate with the Ainur—that which makes them godlike in knowledge compared to all other peoples. Through Ilúvatar’s narration over this vision, they even see the future history of the World unfold. This will give them foresight—but it’s not complete, nor fully predetermined; what they’re looking at is still just a hologram, a pre-production film.

It is in this vision, this glorious animated PowerPoint presentation, that the Ainur first begin to see other things that they had not imagined, things that come from Ilúvatar directly and not from their individual contributions. Most importantly, this is where they first glimpse the Children of Ilúvatar—the catch-all term for both Elves and Men, the peoples fated to populate the coming world, each in their own time.

Note that the Ainur themselves are not called Ilúvatar’s “children”: the relationship between their creator and these two distinct classes of beings is not the same. While the Ainur will always be mightier than both Men and Elves by a long shot, the Children of Ilúvatar still present a great mystery to them precisely because they are not like them. The Children are exotic, alien, and seem to reflect parts of their maker that the Ainur have not understood. And this fascinates them. Which makes sense—aren’t things different from us usually intriguing? Who doesn’t love a good mystery?

The Ainur are wowed by these (still hypothetical) Children and feel an immediate affection for them. Ilúvatar tells them that he has chosen a specific place for these Men and Elves to live, “in the Deeps of Time and in the midst of innumerable stars”—which is to say, the Earth. Arda, it will be called, a much smaller habitation within the vastness of the universe. Immediately, a bunch of the Ainur desire to go to this place and get involved with these strange new beings. Of these, who do you think is the most anxious to go?

Well, Melkor, of course, who had wanted to create things of his own to govern. And after all, this may be the next best thing! Tragically, he lies even to himself at first, claiming that he simply wants to go down and make things right again, to “order all things for the good of the Children of Ilúvatar.” Sound legit? Of course, what Melkor really wants is to have servants, “to be called Lord, and to be a master over other wills.”

Ilúvatar makes a few interesting points about the nature of the World they’d helped to shape, and here we are introduced to three more of the Ainur who will play major roles in upcoming events: Ulmo, Manwë, and Aulë. Ulmo’s voice in the Music had focused on the concept of water, so that will become his forte. Winds and air had been Manwë’s aerial style, so he’ll have mastery over those. And the substance of the earth itself, like rocks and soil, had been Aulë’s—let’s say percussive—contribution, so he’ll get to shape those in ages to come. But because of Melkor’s earlier discord, dangerous extremes of weather and temperature have also been introduced into nature, things like “bitter cold immoderate” and “heats and fire without restraint.” Still, Ilúvatar assures the Ainur that because of such extremes, other wonderful things can and will happen—the cold allows for snow, which can be beautiful, along with “the cunning work of frost.” Fire creates steam from water, vapor collects into clouds in the air—now the skies can look more awesome!

Ilúvatar’s point is that the results of Melkor’s meddling can be worked with, and right away the other Ainur become excited at all the possibilities; Ulmo and Manwë will even have a bromance over the many ways their elements can intermingle. It’s interesting to note, however, that in the mind of Ilúvatar, Melkor and Manwë are as brothers. Here, then, is a familial bond of sorts that predates any actual genetics, though their relationship will play out more like sibling rivalry than anything else.

Anyway, at this point, Ilúvatar switches off the vision abruptly, ending it before its full runtime. And this means that while the Ainur have learned much of what will come to pass, or could come to pass, they don’t know everything. They don’t know how it’s all going to end. They didn’t even get to the part of history where Men are supposed to take over on Earth and Elves reach their ultimate decline. Ilúvatar is keeping that ending to himself, for now.

So yes, the End of the World is under wraps. It’s the final act, the final reel, that even the Ainur don’t get to see. So neither do we. Welcome, reader, to the human condition—am I right?

But seeing the Ainur so anxious to begin, Ilúvatar calls out “Eä!”—simultaneously naming and creating the entire universe according to the vision. And within that universe, the tiny little Earth, Arda, is also formed. Now at last—yes, after all the hoopla and hypotheticals—actual existence has come to be, and now the Void and the Timeless Halls aren’t the only things around. Instead of being nearly everything, the Void is just a place outside of Eä (AY-ah).

With both Eä and Arda now in existence, those Ainu most eager to enter it—fourteen of the mightiest Ainur—now come forward. Ilúvatar will make them custodians of this world, but only on the condition that they’re in it for the long haul. There’s no going back. When Arda’s time is done—however many ages that will be—only then will they be released from this service.

And so these fourteen volunteers become the Valar, the Powers of the World, and down they go…

And as soon as they’re in, they’re caught off guard. It’s in a very raw state. Whaaaa? Sure, they recognize it—yeah, this is the place they’d seen in that cool vision—but it’s not fully formed yet. It’s like unbaked clay still in need of shaping. But the Valar (singular, Vala) are nothing if not industrious and optimistic—particularly the three elemental buddies Ulmo, Manwë, and Aulë, who spearhead the operation. Of course, Melkor is here, too, and he tooootally for sure wants to help. He’s actually rather pleased to see it in this uncooked condition. Straightaway he starts meddling with the others’ work, spoiling it. He’s the most powerful Ainu, remember. And, delighted to see that Arda was “yet young and full of flame,”

he said to the other Valar: ‘This shall be my own kingdom; and I name it unto myself!’

Basically, Melkor is doing what a bully does when reaching the sandbox first. “Mine! I called it first! And I licked it. All mine.”

Which is a no-no, if Manwë has anything to say about it. In fact, Manwë will be given the very role that Melkor really wants for himself: King of the Valar and lord of Arda. Manwë then summons spirits—beings lesser than he, some being other Ainur, some not—to help him deal with the Melkor problem. (“The Melkor Problem” could very well be a nickname for the entire First Age of Middle-earth, as we will see.)

Because they’re in the World now, the Valar can take physical shapes. There was no need to before, and sure, they can still go about invisibly, bodiless, whenever they choose. But now they choose Earth-like forms for themselves. Since their love for the Children of Ilúvatar had inspired them to come down in the first place, they select shapes reminiscent of those they’d seen in the vision. Remember, though, that the Children haven’t appeared yet, so for any given Vala it’s still just guesswork as to what Men and Elves will really look like. Certainly the Vala will have humanoid features, and the text does describe some specifics in the next chapter.

Then there is this:

But when they desire to clothe themselves the Valar take upon them forms some as of male and some as of female; for that difference of temper they had even from their beginning, and it is but bodied forth in the choice of each, not made by the choice, even as with us male and female may be shown by the raiment but is not made thereby.

Gender is an artifact of the World, and so the Valar choose to manifest in body according to their core temperament. It’s marvelously philosophical despite being such a short passage, but it’s still open to our interpretation. The Valar do not procreate, are not of the World itself and therefore have no biological connection to nature, yet we will also see some of them—not all—join with one another as spouses…though it’s possible these bonds began much sooner. Still, these things are established later on.

Like gods in pantheistic mythologies, the Valar can choose forms either splendorous or terrible. Even Melkor has a choice, but his temperament and his malice naturally lends itself to a horrific form. And he makes sure to appear in greater majesty than his brethren…

as a mountain that wades in the sea and has its head above the clouds and is clad in ice and crowned with smoke and fire; and the light of the eyes of Melkor was like a flame that withers heat and pierces with a deadly cold.

Melkor splits from the other Valar and makes war against their labors. He is impotent to create new things but is highly skilled at corrupting what has already been made.

As the Valar form up the lands of Arda, Melkor breaks them down; as they delve, he fills; as they contain, he spills. He is the mightier still, but he is also alone; they are more numerous and they cooperate with one another, working in concert and in harmony as they did in the Music. Slowly, over untold ages that even the Elves cannot account for, Arda comes together and is “made firm” despite Melkor’s sabotage. It’s not fully as the Valar intended, but neither is it a ruin. It is still Arda, but it is also Arda Marred.

A final word about the Valar, which may be said of all the Ainur (and we will meet a bunch more in the Valaquenta, our next installment): as powerful spirits formed from the sheer thoughts of Ilúvatar, they can be thought of as vast as the world, yet as fine-tipped as a needle. There is a particularly twisty but fascinating sentence in the Ainulindalë that describes this, but it amounts to referencing both the enormity of a Vala’s power and the precision and interest with which they approach this world they love. Why would such mighty cosmic beings come down into this tiny little world when the universe itself is so vast? Because even small things are of worth. The Valar had fallen in love with the vision, and wanted to keep and protect it, and make it thrive. One might just as well wonder why a wise old wizard would take an interest in a single hobbit.

It can also be asked why Ilúvatar allows the troublemaker Melkor to enter into the World at all. That’s the universal question, isn’t it? Why would an all-powerful god allow discord to exist in the World and spoil its harmony? In the context of Tolkien’s legendarium, it’s not enough to consider the conditions placed upon the Ainur who volunteered to enter it—forever to remain within it, while it lasted. Because then you could say Melkor’s evil could be contained in this way, but when you see what his long term fate will be, you’re left still wondering. So for now, instead consider what “things more wonderful” will be devised in the wake of his deeds?

Read on; we will see some of them some soon.

In the next installment, we’ll dive into the Valaquenta and Chapter 1, “Of the Beginning of Days,” where a cast of mighty characters work out a means of exterior illumination.

Top image: “Ainulindale VIII” by E. F. Guillén

Jeff LaSala can’t leave Middle-earth well enough alone. His son has a Quenya middle name, for Eru’s sake. He also wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel and some other sci-fi/RPG books. Oh, and works for Tor Books.

I love Tolkien’s use of music as a metaphor for the act of creation. C.S. Lewis did this, too, in the Narnia books – Aslan sang Narnia into existence in The Magician’s Nephew – but not with anywhere near the depth and complexity that Tolkien did. (Not a bad thing, just a different thing.)

Great summary of, as you say, a very dense and important few pages!

I read half this post, then reread Ainulindalë, then finished this post. I’m looking forward to the next post!

Oh, if only Ralph Vaughan Williams could have provided music for this! But he died in 1958, and would have Tolkien wanted him or anyone to go ahead and provide music to read by to what was still in manuscript??? Tho’ I think someone composed music later–in the ’60s?–for “the Road Goes Ever On”. . . need to do some research, but the Tor staff or readers will know.

@drcox, yep, The Road Goes Ever On: A Song Cycle, by Donald Swann, was released in 1967. I’ve never heard a recording of it, but I tracked down the sheet music once and tried to pick out the tunes on a piano, with indifferent success.

This is so good – thank you! Silmarillion for the rest of us!

@drcox – I second your nomination of Vaughan Williams! I imagine some of it might have sounded like the final movement of Hodie (“Ring out, ye crystal spheres…”). And maybe that striking “Em-MAN-u-el” motif would have been the notes for, “Il-LU-va-tar!” :)

Any living classical choral composers you’d nominate? I confess my knowledge there is a little limited. (Patrick Doyle might make a good orchestral composer for the subject, though.)

I for one daydream about Mike Oldfield producing an album called The Music of the Ainur. I’d geek out over which section ends up (inevitably) including tubular bells.

@2/@3 — Yes, I had the book of piano music at one point (and also had indifferent success) although TBH I don’t know if the compositions really fit the way I’d always “heard” the music in my head — a lot of it was too … jaunty? I did like his take on Errantry, though. Hey, look what I found on YouTube!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=690OiCByWRc

(The songs start at around 27:00.)

Myself, I envisioned something more like medieval or Renaissance music, either vocal or instrumental. For the actual Song, maybe something like Allegri’s Miserere?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NmWZIPri38Q

I have read the Silmarillion so many times I have lost count. It is by far my favorite of his books.( not that LoTR and the Hobbit aren’t great) I ( I would guess like many) visualize what I am reading, and the visuals that that this part of the book gave me are simply amazing. like a concert, not covering a little stage in a theater, but a stage that goes on forever filled with never ending musicians.

I like how you’ve made clear there is nothing cool about Melkor. That he is a nasty, petty little power monger. One of the subtle themes of the Silmarillion is how evil makes the evil one smaller and lesser than they once were.

Good lord, the choral work I can imagine for any proper soundtrack of this book. Layers upon layers of interwoven harmony. You might need two or three full symphony chorales just to get all the layers, and that isn’t even beginning to pull in the instrumentalists.

And somebody with a reverberating basso profundo for Ilúvatar. Maybe also for Melkor and Manwë, though I would also accept skilled baritones for them. Get a crystalline soprano for Varda, and maybe a lush mezzosoprano or a contralto for Yavanna…

Wow. Just thinking of it is kind of amazing. :D

9. princessroxana, thanks, and yes, that’s one thing I hope to reiterate as time goes by. Melkor is insanely powerful, yes, but he diminishes his own power over time even as he leaves stains on everything. Such is evil.

I’ve encountered people who seem to try to sympathize with Melkor like he’s some sort of wronged party. I don’t buy it.

“Never since have the Ainur made any music like to this music, though it has been said that a greater still shall be made before Ilúvatar after the end of days. Then the themes of Ilúvatar shall be played aright, and take Being in the moment of their utterance, for all shall then understand fully his intent in their part, and each shall know the comprehension of each, and Ilúvatar shall give to their thoughts the secret fire, being well pleased.”

So Tolkien predicted the coming of One Direction; interesting. :)

Ouch, mndrew.

Ouch.

I’m really looking forward to following your posts. I loved LotR and The Hobbit, as well as the other writings of Tolkien’s that I’ve read, but the Silmarillion overwhelmed me and I know I didn’t get as much out of it as I could have. For one thing, I tend to read really fast to find out what happens next and that isn’t really conducive to something as complex as The Silmarillion. Thank you for giving me this opportunity to slow down and savor the experience.

But even from the first time I read it, I thought this creation story was the most beautiful.

Oh, this will be fun. Plain-spoken for easy comprehension, but effectively evocative and rather entertaining.

“One of the subtle themes of the Silmarillion is how evil makes the evil one smaller and lesser than they once were.” Ah, fantasy.

Definitely among the most beautiful of creation myths. The concept of world-building through music is wonderful…and the concept of evil, strife, and discord arising literally from discord—as well as the idea that it is indeed possible to create beauty from discordance—just seems natural. (That the discord was started by an ambitious, haughty prima donna seems especially apt to anyone having real-world experience with actual musicians ;-).

I have also always been intrigued not only by the idea that Ilúvatar requires the assistance of the Valar, Elves, and Men to complete his vision but also by the resulting implication that Eä and Arda contain entities that Eru may understand but did not create (at least directly)—and that this separation adds an element of serendipity that is essential to how the world develops. It has always struck me as an amazingly clear way to reconcile the coexistence of free will with an omnipotent/omniscient creator; this aspect was made all the more salient because, at the time I first read the Silmarillion (about age 14), the teachers at my Catholic high school could not explain this element of theology in any way that I considered coherent! (Surely it’s no coincidence that our dear Professor wrote something that converged on this particular theological question?!)

Partly for these reasons, over the years I’ve frequently been reminded of the Ainulindalë whenever I’ve learned about real-world concepts (e.g. quantum theory, chaos theory, emergent behaviors) in which knowable, structured behavior arises from non-deterministic elements.

An excellent primer for a book not nearly enough Tolkien fans read!

Jeff, your comment that Aulë was likely a percussionist made me start to speculate whether the other elemental Valar could be linked to families of musical instruments, e.g., Ulmo = strings, Manwë = woodwinds, Melkor = brass? I almost want to make Manwë a trumpet, though.

3, 5, 6, 7, 10 –Thank y’all for the comments and info! I listened to the whole album of Tolkien reading ‘n music. Lovely! As I was reading today, I was reminded of Vaughan William’s Sinfonia antartica. Modern composers . . . yes, Patrick Doyle, or John Williams . . . (FYI, as I’ve mentioned before, I have not seen Jackson’s adaptations, but have heard a track or two on the local classical station).

Shawnbou @@@@@ #17:

If we’re talking representing the Valar via instruments instead of voices, I move that Manwë probably has too deep and profound a tone to him for a trumpet. I’m more thinking French horn.

I’m actually leaning to Tulkas for the trumpet section. And I’m waffling between Aulë and Ulmo for the tubas and trombones. Cello or the contrabass would also be acceptable for Aulë and Ulmo.

Varda gets the violin section but, if this orchestra has a couple flute players, she also needs a flute soloist. Possibly a piccolo. (The Seattle Symphony has an amazing piccolo player who can do some stunning high crystalline notes that would be exactly what I’d want for putting Varda’s kindling of the stars to music.)

Yavanna gets the violas, or, if we’re representing her with winds, an oboe solo. Because woody sound.

For Melkor, you’d also need percussive chimes to really get into portraying the discord of Melkor’s themes. And he gets the tympanis too.

And in fact I was having a discussion with my wife tonight about imagining the Silmarillion as a symphony, and how the composer would have been doing all sorts of fun things with deliberate dissonance and eventually bringing it all together into one great theme. And there would be all sorts of tricks with time signatures as well, the sorts of things that make orchestra players weep and yell “You want me to play 13/7 for HOW MANY MEASURES?” :D

@17 , @19: I was actually thinking contrabassoon for Manwë, he needs that brooding aspect. Mandos seems like maybe the trumpet, but I was thinking that for Tulkas too…although perhaps he requires a squadron of highland pipes?

For everyone who wants to hear Ainulindalë: The opening soundtrack to the first Jackson LOTR movie follows the outline pretty well. Pay particular attention to the theme that I think is called Mordor’s March: dahhh-DAHHHH-dahh-da-da-dahhhh, “loud, brassy, and repetitive.” You hear it over and over, and yes, mostly when Mordor’s forces show up, but it comes in early enough that I think that it can also be called Melkor’s Theme.

But remember how Eru transforms all the works of Melkor? Put in the last disk for ROTK and go to the scene where the Dark Tower falls. Pay close attention. You’ll only hear it once. Howard Shore, ILU.

Great article! My college philosophy thesis was about Tolkien, Lewis, and Plato, and music in creation. So this is wonderful, fascinating stuff to me.

What is meant by “Gender is an artifact of the World”? Does that mean there was no gender until the World was created? Why then does Tolkien say, “for that difference of temper they had even from the beginning”? I think gender is an essential characteristic of each person (Ainu, elf, or man), given to him or her by Iluvatar when he creates them. I wouldn’t call gender an artifact, if by that you mean it is a sort of tool that only exists because bodies exist. If God had made me an angel and not human, I would still be female. I think. Could be wrong. :)

25. Sarah, I only mean in its physicality. The pre-Eä Ainur might have had the same temperaments, I’ve no doubt. They’re core selves existed before biology did. So I think, when entering a biological world, they choose to “clothe” themselves in biological Earthlike forms and those temperaments manifest as gender. I bet it’s not even a perfect fit, just one that works best for them. That’s all I mean. Just the same, spoken language is an artifact of the World. The Ainur clearly had no need of actual speech, communicating spirit to spirit as with telepathy, or perhaps something more perfect than even that. But if they came into Arda and wanted their physical bodies to communicate verbally, they’d have to use a spoken language. And then those words, those sounds, the sounds of their voices…all of that is just a translation of what’s already in their minds.

I confess to having a bit of sympathy for Melkor, at the very beginning; it would be incredibly vexing to be told, “hey, you think you’re doing your own thing, but it’s all My Ineffable Plan after all.” (That does not in the least justify the rest, of course.)

Also: sticky notes are cool, but they need alt text in the code, or text descriptions below them, to be accessible to all!

Jeff – this was a wonderfully beautiful article. I haven’t read the Silmarillion in years…yet reading this immediately brought back the wonder and joy I experienced upon first reading the book itself. I guess I should now pick it up again so I can read along. I can’t get wait until you get to my favorite chapter – Turin Turambar – oh what a riot of love and tragedy. And I’m also interested to see what you make of (what I found) the toughest chapter to get through – “Of Beleriand…”

As for this – I struggle a bit with reading this initial chapter – as much as I love it, I can almost never fail to compare it to my Christian faith(probably something Tolkien would not have approved of!)…and in so doing, it’s hard for me to enjoy it in its isolation as a creation myth. I do so love it though and it stirs my soul.

Dang it I was going to read these without going to reread the book again. That was stupid…why would I deny myself that join and yeah can’t do it. As amazing as the first part is it also highlights some of my issues with Tolkien’s philosophy and some parts of it I really like. The whole beauty through sorrow (hello Elves) is amazing and wonderful. We can get to the others later but the one here is the whole “going after glory is innately evil” which I don’t remember being as prominent here as you seem to indicate it is (certainly present in other parts so I am likely wrong and was just dismissing it because of my own prejudices this early) certainly competition can be unhealthy but it is also a great motivator and leads to many wonderful things being done. And people NEED motivation – otherwise it is way to easy for people to sit on their buts and not do anything.

While I get Tolkein wrote and created art for his own pleasure and the pleasure of creation – that is not average human way of thinking. Would be great if it was but it isn’t (at least not in my experience).

This also surfaces a major problem I have with the movies. Music as power is a theme throughout ALL of Tolkein’s works and one the movies completely removed. I mean there is great evidence that Bombadill IS illuvator so by not having him in the movies you removed, the creator of the world, from the movies.

Never a decision I will understand.

wow what is with all the content removed? WHAT could people be writing on this that would need to be deleted??? Sigh. State of the world bothers me so much these days…

I remember from my college days, taking intro to Jazz, there was a movement where the musician (usually pianist) would intentionally hit a note out of key. But it would be repeated until the listener realized it was on purpose. I have always though about this when reading about Melkor’s discord. I wish I could remember what the movement was called.

15. AeronaGreenjoy:

That’s just the long view on it. Big picture evil, not necessarily the everyday horrors.

29. Sonofthunder, I cannot wait for Túrin of Many Names myself. It’s a doozy.

I’m actually looking forward to having fun with the action-packed “Of Belerian and Its Realms.”

Regarding faith, just remember that Tolkien wanted his world and its creation and its divine powers to be compatible, not parallel. I think it’s fine to make inward and personal comparisons (I do), but part of what makes Tolkien’s work so approachable is that it doesn’t beat you over the head with anything. It lays it out all down and lets you draw your own conclusions. I think I know what some of his were, and I think I agree with some of them, but he doesn’t proselytize. That said, the echoes of realistic human flaws are thick in The Silmarillion. I think there’s a lot to recognize in ourselves.

30. dwcole, I’m definitely going to avoid talking about the films here. I really love them—they’re the best cinema to date, if you ask me, despite their flaws—but they are absolutely different mediums and I generally prefer book/film comparisons.

31. dwcole I’ve been wondering the same. You know Tolkien—such controversy! Such edginess. ;)

Re: Comments removed above were double posts, plus long quotations/links to books where the relation to the original post/Tolkien/The Silmarillion was unclear. As we’ve requested before, if you want to contribute to the discussion, there needs to be some commentary involved–without any context, long passages from apparently unrelated texts, as well as unrelated links, will be considered spam.

Ohh! Moderater, you guys are the best. :)

Ian @@@@@ #20: Ooh, piper corps for Tulkas? I like the way you think!

Contrabassoon for Manwë? Also an intriguing possibility. I am not entirely sure I’ve ever actually heard one! This requires investigation.

Jenny Islander @@@@@ #21: I know the loud, brassy, and repetitive theme you’re talking about; I’ve seen the movies enough and listened to the soundtracks enough (I’ve even got the super-fancy full extended soundtracks that have every single little scrap of music in the movies) that that’s kinda emblazoned into my brain. ;) I’m not a hundred percent sure I buy it as a theme for Melkor though, just because it’s not quite dissonant enough to match what I’m envisioning!

But I will totally listen for this next time I take a spin through the soundtracks. :)

@Sonofthunder no. 29: Tolkien was, IIRC, very, very Catholic. So I think you’re OK. :)

KadesSwordElanor @@@@@ 32 – I took a musical theater class in college, and the professor was also the conductor for the local resident professional theater company. The spring that I took the class, they were doing a show called “Crazy For You,” which is basically a Gershwin Revue. Some of the music utilized the technique you described of hitting a deliberate off-key note. My musical ear was not attuned enough to catch it on the soundtrack, but he indicated that he got a lot of grief from the musicians who had to constantly play out of key music. It was apparently very awkward for them to deliberately misplay the songs as necessary.

27. katenepveu, you made a great point. We’re looking into the sticky note text…

As for sympathy for Melkor…I would hope that he’d be vexed by Ilúvatar’s words, given the evil he’s willing to enact to get his way (or try to get his way), but I’m not sure he is. He ignores those, after all. My impression is that his secret anger comes from being publicly called out for his discord. It’s one thing to deviate, it’s another to keep others from doing what they wanted (to sing Ilúvatar’s theme). He’s a saboteur.

#38 @@@@@ JamesP I actually saw that musical on Broadway, probably 20 some years ago, and forgot about that aspect of it. Boy did you just stir some nostalgia.

JLaSala Thanks for the pronunciations. If my ear memory is serving me correctly Martin pronounces it Ill-ooh-VA-tar, barely pronouncing the r at the end.

Wonderful article (as always) :)

This is the second tor.com article in two consecutive weeks where the Sound of Silence is linked. One can get addicted to the song this way :)

I loved this! I was going to wait but I really want to follow the primer, I think I’ll manage to read a chapter every two weeks. I usually try to read in original language but The Silmarillion is challenging enought, so I’ll start to read my Spanish translation copy that lies abandonned at home.

I hope the Dramatis personae and the sticky notes will be regular sections!

“Welcome, reader, to the human condition”, excellent!

I find interesting that the action starts with music and only after with sight, interesting because The Bible (if I remember correctly) started with light.

Also, interesting points about the Valar fallen in love with a vision of Earth and the parallel of a great wizard being interested in a hobbit.

Creation myth as a musical piece, absolutely captivating! Out of curiosity, I wish we knew how Tolkien “heard” it and how he would have composed it!

Regarding the Donald Swann pieces: I too obtained the sheet music in 67-68 and picked out the tunes on the piano. I was never so disappointed. I had expected something magical, and instead I got melodies that…like hoopmanjh@7 above…didn’t even begin to evoke what my imagination had conceived. Of course, it probably didn’t help that I had already made an attempt to develop a melody of my own for “The Road Goes Ever On” (and maybe a couple other songs from LOTR). I hadn’t been exactly satisfied with my own, but it was already stuck in my head before I heard Swann’s. I disliked Swann’s so much that I was very unhappy to hear that Tolkien approved of it.

annathepiper@19: If Manwë were to be French horn, he would need to be not just a single horn, but a chorus of them in chords, right? (But it would have to avoid sounding like “the wolf.”)

Ian@20: Oooo…contrabassoon! Maybe even better!

There’s always Camwyn’s “Silmarillion in 1000 words”, if you think this is too long. Unfortunately, she deleted her LiveJournal, and her website is down. Fortunately, it was reproduced elsewhere. :-)

Ah, she moved it to Dreamwidth. :-) https://camwyn.dreamwidth.org/333943.html

Hey, if anything, Aulë music might be less percussive and more like a stalacpipe…

Of course, the actual Music of the Ainur was just disembodied spiritual voices likened to instruments after the fact to give the Elves some vague idea of what it might have been like. But I bet once instruments were devised, the Valar loved them—because the Children made them.

I wonder if Yavanna likes, or dislikes, the didgeridoo.

Thanks for posting this series. Most illuminating.

I read LOTR twice through when I was in high school, and found the appendecies to be some of the most interesting stuff. When I saw a poster at B. Dalton’s advertising the upcoming publication of The Silmarillion (yes, it was that long ago), I could hardly wait. One of the few books I bought in hardcover.

But I was stymied by the dense prose, and had the most difficult time getting into it. I gave up after less than 100 pages, and didn’t really get anything out of it. I was looking for a straightforward narrative, but never found one. I realize now my mistake, but I was hugely disappointed at the time.

Your Primer seems more in line with the LOTR appendecies: very clear and understandable, and (so far, anyway) a great deal of fun to read.

Thank you, Jeff. I really look forward to your next instalment.

srEDIT @@@@@ #43:

Oh yeah I would totally be envisioning the Valar represented by all of the instruments of a given type, not just one, unless the specific part of the symphony is calling for a solo. But I hadn’t thought of your idea of a given Vala or Valier needing to be represented by their own little cluster of instruments, and the chords representing their own complexity of being. That’s an excellent thought!

Regarding how evil makes one smaller, I can’t but thinking of the doctor who quote:

“You’re the size of a planet but on the inside you are just. so. small.”

Thank you for this wonderful series; I look forward to following with you. One Direction, forsooth!

Speaking of musical instruments, Nienna is definitely an oboe. And I must insist for personal reasons that Iluvatar is a euphonium…

I also do not understand the reference to sticky notes. Is there something I am not seeing on this page?

Re: “sticky notes”, we’re talking about the leaf-shaped images that Jeff has used to highlight helpful information; we’ve also added alt text to these images, which should make them more accessible, going forward!

The other had now achieved a unity of its own; but it was loud, and vain, and endlessly repeated; and it had little harmony, but rather a clamorous unison

That’s really the core of the story, isn’t it? On one side you have freedom and improvisation and harmony; on the other side, you’ve got opposition, but no diversity permitted within it.

Brilliant article. You did a great job of navigating us through the subtleties. You were particularly sensitive to the kinds of mistakes 21st century readers might make if they don’t read carefully. You certainly helped me to better understand. Keep it up.

I would note that gender is not only an artifact of the physical world for the Ainur, it is a leftover piece of Tolkien’s original writings of these materials, when the Valar not only were gender in name but also in reality, to the point that the Maiar are their actual children, not just lesser beings of the same type (Eonwe (sorry not sure how to Umlaut on this keyboard) is Manwe and Varda’s son, for instance). I suppose we could assume that the “making” of the Maiar was more similar to the “making” of Athena in Greek Myth and less like the “making” of Apollo and Artemis, so that actual Valar sex might not have been necessary to “make” the Maiar in those original thoughts of Tolkien.

@56, for this series I’m keeping away from the History books and just addressing the “final” (as much as it can be) version of this story, disregarding the drafts that Tolkien himself abandoned. I’m glad he left behind the notion of the Valar having theirown children. They’re much more original this way

Thank you for this ecapsulation of The Silmarillion! Honestly, I haven’t touched it since I devoured The Hobbit and LoTR when I was in 4th grade (10 yrs old). I got the Silmarillion, but found it completely impenetrable at that age, giving up after some 30 pages. It certainly would be neat to return to it again!

Awesome. Those of you who are really dusting off your copies of this and giving it a go, thank you for saying so. It’s very encouraging.

Definitely enjoying this and looking forward to reading more. I was surprised by your argument that the relation of the Ainur to Iluvatar is not parental. In chapter 2, Aule describes his relationship to Iluvatar explicitly as that of a child and his father. Considering that Iluvatar created the Ainur, it’s hard for me to see how their relationship cannot be parental. Granted they are not of the Children of Iluvatar, but maybe that’s a semantic issue. After all, Eru is called Iluvatar in Arda, so his children there are the Children of Iluvatar, so perhaps the Ainur are the Children of Eru? I’m pretty sure that in a later chapter Tolkien also describes the ideal relation of the Ainur to the Children as that of elder siblings to younger, which would suggest that they share one parent.

@@@@@ 30 dwcole – I’ve read a lot of arguments about what Bombadil actually is, but he is almost certainly not Iluvatar. In the Letters, Tolkien explicitly states that the One does not enter into the world himself. Also, in LotR, it’s explicitly stated of Bombadil that “power to defy our Enemy is not in him,” and that Sauron would conquer Bombadil along with the rest of the world if he recovered the Ring. Obviously, if Bombadil were Iluvatar, this would not be the case.

Hey, Gaius, the part you’re referring to in “Of Aulë and Yavanna” is itself made as an analogy. Mostly. Truth is, I’m just trying to make a distinction between the Children and the Ainur when it comes to their relationship with Ilúvatar. Hence I still say godparent or foster parent because that relationship is still important but it just isn’t the same as the “proper” children. I don’t think it’s mere semantics. To Tolkien, word choice was extremely deliberate.

But I do take your point. You’re not wrong.

The BBC radio version of Lord of the Rings had settings of the songs by the late Steven Oliver, most of which I heartily recommend – his versions of the Lay of Gil-Galad, the Rohirric poetry and Bilbo’s last song, in particular, though his ‘A Elbereth Gilthoniel’ is just wrong.

But if I remember rightly, didn’t Tolkien borrow the idea of creation through song from the Kalevala?

Yeah, sorta. He had plenty of influences, given his scholarly pursuits. From letter 257, he wrote:

Here is a German electronic artist’s impression of part of this story:

https://www.discogs.com/m%C2%B2-War-Of-Sound/release/122701

Recommended

You inspired me to finally buy The Silmarillion (my old copy got lost somehow between moves). Over five years ago I started, and although it was a bit rough getting into it at first, it grew on me and I was really enjoying it. And then … it got lost and I didn’t find it for a long time. By the time I did, I couldn’t get back into it and I didn’t feel like rereading it. Now I’ve got it and I am loving your primer! I wish it was posted more quickly, though, lol.

I love all the discussion about the instruments and the Ainur. In my opinion, the most complex, layered, and angelic music is 16th century choral music without instruments. Stuff like Tallis, Palestrina, and, of course Allegri. Gives me chills, it does! If someone could write some really, really great music like that I would be all over it!

Thanks, Laura. Alas, real life intrudes a bit, so it’s hard to tackle the Silmarillion faster than every two weeks. But actually, I rather like the idea of spreading it out and enjoying it for a longer period of time anyway.

Next episode is next Wednesday and will be rather weighty!

Yay for Tallis. Rather coincidentally—until I later came to know of the composer—that was the name I gave the protagonist of my Wizards of the Coast Eberron novel some years ago. Not so much an English composer as a half-elven good-intentioned outlaw :)

When I first read the Silmarillion I hadn’t realized Tolkien was Catholic (nor was I particularly knowledgeable about Catholic theology or philosophy aside from the basics). But now it’s fun (for me) to see how it has permeated his work, and for me at least, sometimes is a more helpful illustration (or at least one that resonates with me the most personally) of them than anything else :)

The importance of free will in Catholic doctrine is pretty crucial and so that would definitely be an important part of his conception of the world, the fall, etc. And people have wrestled with how God could allow evil in our own world as well.

“It might be tempting to sympathize with Melkor as a nonconformist, to regard him as simply thinking outside the box—but as we’ll see, that’s not really the problem. It’s that Melkor wants to own the box. ” – ha, I love this.

““Beauty from sorrow” is worth remembering. ” – this is, of course, also a pretty fundamental aspect of Catholic (and Christian in general) theology.

The idea of femininity/masculinity being an inherent part of the soul (and not to be confused with feminine/masculine traits or interests as defined by society) is also a pretty Catholic one and I could probably blather on at length about that kind of thing but I won’t.

Those general comparisons aside, I think part of the reason the Silmarillion works in part because his theology is not a direct copy of Christianity and in the surface details there are several things that ‘conflict’ (what I actually think is especially interesting is the idea of death as a gift to men later on).

Nienna is a harpist, of course :) Or Amy Lee, pehaps ;) (BUT SERIOUSLY HOW DID WE GO 51 COMMENTS WITHOUT MENTIONING THE BEST VALAR).

Lisamarie, the answer to your last question is: because we haven’t met her yet! Nienna rocks, but we have to wait for the Valaquenta. Which is nigh.

Amy Lee. I can get behind that, though I don’t know that Nienna would be as aggressive-sounding as a young goth-rock singer can be.

That said, if we’re going to do musician comparisons, I think Mandos and his wife, Vairë the Weaver, would more akin to Dead Can Dance in the Music of the Ainur…

@68 Ahem. Nienna is CLEARLY either Joannie Mitchell or Janis Ian. You just know that Nienna wrote the words to “I learned the truth at 17…”

@59 – well, I was thinking more along the lines of Even in Death (the Lost Whispers version), Secret Door, Swimming Home (which actually is about crossing over and with all the water imagery always reminded me of the Eldar being called home) or the acoustic version of All That I’m Living For ;)

Sorry for the lost post. I think Tolkien’s legendarium is a useful framework by which to examine how (or whether) the Christian God could be both all-powerful and all-loving.

–Spoilers about topics discussed in “Laws and Customs Among the Eldar,” a manuscript that was published in Morgoth’s Ring.–

In the manuscript, the Valar express hope for a world that they refer to as Arda Healed. Their hope is that the marring of Arda will eventually produce a world that is greater and more fair than Arda was before it was marred.

If Ilúvatar was both all-powerful and all-loving, then logically he would have simply willed Arda Healed into existence, or a world that was just as good as Arda Healed. He would not have required the Ainur or his children to endure the misery of Arda Marred. Therefore, it seems reasonable to conclude that Ilúvatar was not both all-powerful and all-loving.

One could argue that Arda became marred because Ilúvatar gave the Ainur and his children the gift of free will, and that Melkor used his freedom to rebel against Ilúvatar and fall into evil. I think this argument is reasonable, but it’s not completely convincing. If a person has free will, they are still unlikely to do things that are contrary to their nature. To take a bizarre example, there is no reason why I could not pour orange juice on my head. But I probably won’t because there’s no reason why I’d want to. It’s not in my nature to want to do something like that. Even if I wanted to do something perverse, just to prove that I could, I doubt I’d pick that particular action. Similarly, Ilúvatar could have created the Ainur and his children so that they would have the freedom to rebel against him, but also so that they would have no particular desire to rebel. In other words, Ilúvatar could have created a universe in which all the parts of his creation fit together in perfect harmony with each other. They would still have the freedom to rebel, but they would think of rebellion as being a pointless, perverse act. But that’s not the universe that Ilúvatar created. He created a universe in which people are tempted to rebel. Therefore, the marring of Arda cannot be explained by free will alone.

If Ilúvatar was all-powerful, but not all-loving, then he could have instantly created Arda Healed without any need for the Ainur or his children to suffer through Arda Marred. (One could reasonably argue that it’s logically impossible to create a world that was healed, but never harmed. Even so, an all-powerful being ought to be able to create a world that was *just as good* as Arda Healed.) Instead, Ilúvatar created a universe in which he knew that Melkor would fall into evil and cause the marring of Arda. Since Ilúvatar would not need to do that if he was all-powerful, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that, if Ilúvatar was all-powerful, he was also evil and Melkor was an innocent victim.

On the other hand, perhaps Ilúvatar was all-loving, but not all-powerful. In that case, perhaps he wanted the Ainur and his children to enjoy the benefits of Arda Healed, but he could not simply will that world into existence. So, he came up with a plan. He created a somewhat disharmonious world, knowing that it would inevitably be marred, and that the marring would inevitably lead to healing. Maybe Ilúvatar understood that his plan would work in a general sort of way, but he could not foresee all the specific details. Maybe as far as he knew, an Ainu other than Melkor would fall. Or maybe no one would fall, but Arda would still somehow be marred anyway.

That interpretation makes the most sense to me personally. Ilúvatar was a being of unfathomable power, but he was not “all-powerful,” at least not in the modern sense of the term. For that reason, his plan for bringing about Arda Healed was to create beings who had free will, but whose essential natures prevented them from getting along with each other in perfect harmony. When a being like Melkor (or even Aulë) rebelled against him, Ilúvatar understood that being’s motivation, but he did not necessarily have foreknowledge of specific future events.

(minor edits for grammar and phrasing)

I have always enjoyed the Ainulindalë and the use of Music for Creation. This is not the only place where Songs of Power were used in the Silmarrion. I have been able to compose some music for Tolkien’s songs but I will have to see if there are any from this book that I have put to music.

Good review. But there’s a mistake. They say that there is free will. I’m afraid that’s wrong! Read Tolkien’s book and you’ll see that nobody sings a song that Iluvatar has not planned for them to sing.

@73 I’m not sure that’s how I would interpret it. Iluvatar says that no one can sing in his despite; that whatever lousy lyrics they come up with he will incorporate it into his grand medley and make it #1 with a bullet. That is not, in my mind, the same as saying that he puts the words in their mouths…

Yeah, I don’t interpret it that way, either. I absolutely do believe free will is the whole point. There might even be varying degrees of free will, as I’ll mention in the next installment, but even so, it’s all there.

Having your source in something doesn’t mean the maker of that source made you do what you choose to do. You get to decide. It means the maker of the source provided you with the means to think and do things in the first place; so whatever you do, the maker can take that and rework it for the betterment of all. It’s like if a teacher placed hundreds of letter blocks out for children to play with then asked them if they would like to be creative and spell things with the letter blocks. And for the most part they all do, expressing themselves by forming cool words. Then one rebellious student goes and starts spelling naughty things. Which he had the free will do to. But even that rebellious student is still using the very same blocks the teacher provided; although those naughty things might have been spelled, the teacher can then go and take the very same letters chosen by that student to spell even nicer ones that student hadn’t even thought of. Sorry, kid.

A simplistic analogy, to be sure.

Token grump about pronunciation. There is no “duh” in Ainulindale, and no /o/ in Ainu(r).

Fair enough, Tamfang. Tolkien himself would be grumpy at all the Middle-earth–based articles. :)

My pronunciations are meant to be simple, not academic. But I’ll take your point and amend the “uh” and “nor” accordingly. Thanks.

Duh! There’s no duh!

and

Nu? That’s how you pronounce Ainu?

KadesSwordElanor (40): who’s Martin?

Martin Shaw, the reader of the audiobook Silmarillion. He does an amazing job, aside from a few of the mispronunciations.

Would “dah” (or even “da”) be more complicated than “duh”?

I’m amazed no one has floated Charles Ives’ “The Unanswered Question” (link below) as an example of the music of the Ainur. The first time I heard it this story was all I could think of!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vXD4tIp59L0

Mr. LaSala,

I had a quick question about when the music of Ainur stops. Are the events of the Lord of the Rings still a part of the Third theme? Does the music stop after the events of Lord of the Rings?

Thank You!

Benjamin, only in a figurative sense perhaps. But the three themes occurred during the Ainulindalë and, remember, after the third theme happened for a while, all “the Music ceased.” Then Eä is created after it has already stopped, based on the Music but not during it. Arda is formed, the Valar go down into it, bring the Maiar, etc. The Music already occurred. It’s not ongoing.

That said, remember we get references like this:

Which suggests that such echoes can be found all around. But that’s all it is. An echo.

Or might you be confusing the Third Theme with the Second Music? But even that hasn’t happened yet. That’s meant for the end of Arda.

Okay Gotcha, Thanks

To maybe clarify… I was wondering what time period in the real Arda was based on the The Third Theme and at what point did history end reflecting the end of the third theme. But, I think you’re saying that this ending came after the Fourth Age. Is that right? But. thanks so much!

@85, I think maybe the entire history of Arda is based on the third theme. It says, “The Children of Iluvatar… came with the third theme, and were not in the theme which Iluvatar propounded at the beginning.” So, maybe the first two themes concerned the history of Arda before the Children were born, or maybe those two themes ended up not being used at all. They didn’t seem to have turned out very well.

Or are you asking about the point in Arda’s history at which the Ainur could no longer see Arda in their vision? It says that “some have said that the vision ceased ere the fulfilment of the Dominion of Men and the fading of the Firstborn.”

I suppose it’s possible that only the first part of Arda’s history was based on the music of the Ainur, and maybe that portion of Arda’s history is equal to the portion that the Ainur saw in their vision. But I personally don’t see anything in the text that would lead me to that conclusion. I always assumed that the entire history of Arda is based on Ainur’s music, even if not all of it was included in their vision.

@@@@@ deanfrobischer

Your points make a lot of sense! It would seem that the third theme is the history of Arda when and after the elves and men awoke. Your last point also makes sense as far as the history of Arda being based on the music even after the Valar can no longer see the vision. Thanks, your answer also helped me!

A little off topic, but Mr. LaSala may appreciate it.:

https://www.gocomics.com/overthehedge/2020/04/29

Benjamin – I’m glad I could help!

Hello Mr. LaSala,

I just had a quick question. Do the three different themes of the music correspond to three different time periods? Or do they correspond to different aspects or layers in the creation of Arda? For Example, is the coming of the Children of Illuvatar a signal that the third theme or time period has begun. And just one more question, did the Valar take part in the third theme or was that theme only played by Eru?

Thank You

@@@@@ Benjamin

I’ve been thinking about this. I’ve come to believe that the three themes correspond to three consecutive time periods in Arda.

Ilúvatar’s first theme went on for a “great while” without any flaws. This seems to suggest that Melkor played the part that was given to him for a long time. When Melkor eventually rebelled, he did so by weaving original content into the music, not by rejecting the music completely. Nevertheless, his discord spread wider until the music seemed like two sides endlessly making war on each other.

This seems to correspond to the earliest period in Arda’s history. At first, Melkor was ashamed of his rebellion, and he wanted to help bring order to Arda for the good of the Children of Ilúvatar. He was counted as being one of the Valar. At this time, the “chief work” in Arda was done by Manwë, Aulë, Ulmo and Melkor, and I can’t help but notice that they collectively represent the elements of air, earth, water and fire. The trouble seemed to start when Melkor became a little too interested in fire, to the point that the elements were out of balance and the world was full of flame. Apparently the other Valar told him to knock it off, but he didn’t feel like listening. Long story short, Melkor ended up in a seemingly endless war with the other Valar for the domination of Arda, which is also how the first theme ended.

The second theme began when Ilúvatar held up his hand and began a new theme amid the storm. This theme had new power and new beauty, and Manwë was its “chief instrument.” But then Melkor openly rebelled against the music, and he caused such an uproar that many Ainur fell silent and allowed Melkor to take the mastery.

I think this period began when Tulkas entered Arda and helped drive Melkor away. He was the “new power” of the second theme. Once that happened, the Valar created the Spring of Arda, which was the new beauty. Of course, Melkor eventually destroyed the two lamps and drove the Valar out of Middle-earth. They took shelter in Aman and essentially allowed Melkor to rule the rest of Arda. Yavanna, Oromë and Tulkas were particularly frustrated with the Valar’s apparent inaction.

When the third theme began, it was soft, sweet and delicate, but Melkor was not capable of drowning it out. He had developed his own theme by then, but “its most triumphant notes were taken by the other [theme] and woven into its own solemn pattern.” This state of affairs lasted until the music’s final chord.

We’re told that the third theme concerned the Children of Ilúvatar, so I’m guessing that this period began when the Elves first awoke at Cuiviénen. As it says in the Silmarillion, Melkor did everything he could to dominate Elves and Men. He caused them great sorrow, but it gave them wisdom and beauty. But Ilúvatar’s theme cannot be fully separated from Melkor’s. Even after Melkor was banished and Sauron destroyed, their lies are a seed that lives in the hearts of Elves and Men, and it will “bear dark fruit even unto the latest days.”

So, it seems to me that the first theme started when the Valar entered Eä, the second theme started when Tulkas joined the war against Melkor, and the third theme started when the Elves first awoke. The third theme has been playing out in Arda ever since.

As to whether Ilúvatar played the third theme himself, I personally don’t see any evidence that he performed any music at all. He seemed to exist purely as a composer or a conductor.