In Which An Old Married Couple Squabble, Dwarves Are Stopped Short, and Ents Are Recollected

In “Of Aulë and Yavanna,” two of the most industrious members of the Valar—who just happen to be married—get antsy over their work… with unexpected results. This chapter is a sort of in-world spoiler that Dwarves are going to show up later in the book, and so will Ents (to a lesser degree). Since both races are known well to readers of The Lord of the Rings, this chapter almost feels like fan service on Tolkien’s part. But of course it’s much more, since we’re also witnessing Ilúvatar’s policy, in real time, concerning what he does and does not allow in his creation. This is a short chapter but there’s still much to learn from it. In the case of Aulë, the master of all earthworks, Ilúvatar is both stern and obliging. In the case of Yavanna, it’s more of a nudge, nudge, wink, wink, ‘Hoom-hom!’

Dramatis personæ of note:

- Ilúvatar – founding father of all existence

- Aulë – Vala, smith

- Yavanna – Vala, treehugger

- Manwë – Vala, management

“Of Aulë and Yavanna”

Previously, we met the Valar. Now let’s meet two of them specifically and learn about some of their greatest hits. Aulë and Yavanna are the Miracle Max and Valerie of The Silmarillion—the bickering but adorable older couple whose skills become instrumental to the central story—except, of course, for the fact that these two Valar are insanely powerful. They’re also the perfect example of godlike beings who are aligned with all that is good in the world yet reveal their imperfections in both words and deeds.

We start with Aulë, who, like Melkor, is a victim of his own impatience. He simply cannot wait any longer for the Children of Ilúvatar to arrive. He’s heard so much about them—read all the blogs, seen the concept art, maybe seen some blurry leaked photos—that he just can’t stand it. He’s already a fan. And sure, we as readers might know the Children are coming soon because we’ve seen The Silmarillion’s Table of Contents and know what the next chapter is titled, but to Aulë they could still be millennia away from first appearances. When you’ve lived in the Timeless Halls, apparently “soon” doesn’t cut it.

So, like a fevered artist with a desperate itch, he gives in to his own creative impulses and… Aulë invents the Dwarves! That’s right, the bearded folk are actually the first to show up. Sort of.

Deep underground in Middle-earth he works on them, far from Valinor, and far from the judging eyes of the other Valar—and especially his own wife, Yavanna, who I’m guessing would have a thing or two to say about this. And he knows it. Aulë shapes the literal forefathers of the Dwarven race, rather Golem-like, from the very substances of the earth. They’re kinda sorta Elf- and Man-shaped, and they obviously come out a great deal hairier and a little bit shorter…because frankly, the final form that the Children will take is still “unclear in his mind.”

But close enough, right? And also, because Melkor is still very much at large on Middle-earth, Aulë makes sure the Dwarves are hard and durable. They’ll need to be tough to hold out against that bastard and his minions. And that durability is on all fronts:

Therefore they are stone-hard, stubborn, fast in friendship and in enmity, and they suffer toil and hunger and hurt of body more hardily than all other speaking peoples; and they live long, far beyond the span of Men, yet not for ever.

Now, the moment Aulë’s finished making the Dwarves, he starts to teach them “the speech that he had devised for them.” Which—

Wait a second. The Valar themselves have probably had no use for any spoken language thus far, since they were themselves creatures of thought from the get-go, yet Aulë goes and invents a language—likely Arda’s first!—for the people he himself made? Total nerd move. (Sounds kinda like something the legendarium’s own maker would do.) I’m surprised Aulë doesn’t also design an RPG boxed set (Dwarf: The Delving?) and try to get his friends to play it with him.

But no, there’s no time for that. Within the same hour of the Dwarves’ completion, Ilúvatar himself makes one of his increasingly rare “appearances” and just by speaking up, confronting the smith right there in his secret underground laboratory. With his hands still in the cookie jar of creating living people, Aulë knows he’s in trouble. Caught Dwarf-handed, you might say.

Of course, he’d known he was wrong in doing this, in not waiting for the fulfillment of Ilúvatar’s designs and the arrival of the Children. Not only does he not have the right to create life in this way, he couldn’t have fully succeeded, anyway. As Ilúvatar points out, the Dwarves as Aulë had made them are simply automata and little else, incapable of independent action and free will. Those things can only come from Ilúvatar’s own power.

Aulë humbles himself and submits to Ilúvatar’s judgement. This is something Melkor, by contrast, has never done. Aulë admits his wrongdoing, though he does offer up some reasonable counterpoint, not to excuse his action but to justify his desire. And in this one moment, the relationship between a Vala and his own maker is at last likened to that of a child to a father. Aulë makes an analogy:

Yet the making of things is in my heart from my own making by thee; and the child of little understanding that makes a play of the deeds of his father may do so without thought of mockery, but because he is the son of his father.

First, “without…mockery.” Remember that word—we will see it again in the next chapter in a more devastating context. Second, Aulë is making the point that he is imitating his own maker in his desire to make living things. He doesn’t wish to anger Ilúvatar and wasn’t trying to subvert the plans for the coming of the Children. He’s simply had a lapse of patience, and was doing what Ilúvatar himself placed in him from the first.

Grieving, Aulë even shows that he is willing to sacrifice his work, to destroy the Dwarves he has made. He raises his hammer to do so, but Ilúvatar stops him, accepting Aulë’s humility and his intentions. He spares the Dwarves. The Dwarves will not be scrapped, then, but neither will Ilúvatar allowed them to wake in the world before the Firstborn, the Elves. So he places them in slumber to await a future time—and again, Aulë does not know how long the wait will be.

Though the Dwarves are not among Ilúvatar’s designed Children, they will become his adopted kids. Moreover, Ilúvatar allows Aulë’s work to stand, taking no steps to alter the Dwarves in their imperfect state. And because they were not made in accordance to the Ilúvatar’s own design, he observes that there will be some troubles between the Dwarves and Elves later. They were not devised in harmony with one another, so strife will often exist between them.

I’ve got two things to say about Ilúvatar’s response.

One: that he doesn’t unmake the Dwarves is another example of his policy of working through change. Nowhere in the legendarium does he—as the omnipotent god who could—ever just roll things back. Never does he simply reverse damages. That’s not Ilúvatar’s M.O. We saw it with the musical discord of Melkor, then the marring of Arda directly. When the Lamps of the Valar were destroyed, even they did not try to rebuild and improve them (maybe this time with a Melkor Detector built in and Balrog Repellent sprayed all around?). No, they know that’s not how things go. Instead the Valar learned from what happened and devised something new: the Trees of Valinor!

And so this pattern will continue. Ilúvatar lets things stand, whatever they are, for good or ill, and from them new things will come that are better. Recall his words to Melkor after the third theme in the Music of the Ainur:

…no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined.

Two: this whole “strife shall arise between thine and mine” thing isn’t spite on Ilúvatar’s part. It’s just matter-of-fact observation. It’s like Aulë designed a playable Dwarf race for the Arda MMO, but he did so during the beta phase and without properly accounting for the existing code. So now whenever a Dwarf meets an Elf, there just are going to be rendering problems and communication glitches that will put them at odds. It’s inescapable. And Ilúvatar isn’t offering a patch for this. Again, not his style.

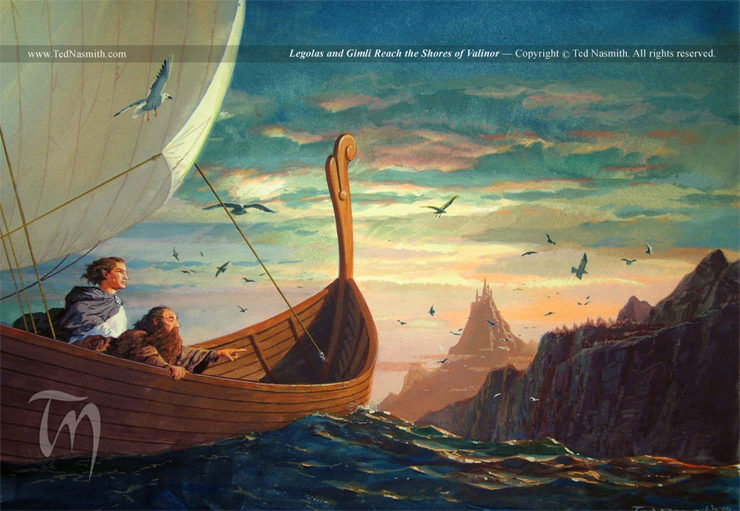

Come to think of it, Aulë’s crafting of the Dwarves could also be seen as an attempt, like Melkor’s, to “alter the music,” and though there will be strife, there will also be things “more wonderful” that come of it. Like a certain familiar odd couple trading banter for friendship far in the future and even sailing together on a westward-bound ship.

In any case, humbled by his screw-up of Project Dwarf but still fairly pleased by its outcome, Aulë finally returns to his home in Valinor and confesses to his wife what he did, and how Ilúvatar reacted. We’re never told when the rest of the Valar find out, which they totally eventually will. Sadly, Tolkien sadly denies us that exchange.

Leaving us only to imagine. Yavanna is not exactly thrilled with her husband. She sees that Aulë is glad of the final result and points out how fortunate he is to be shown Ilúvatar’s mercy. She also points out that because he kept his project from her, his Dwarves will lack the proper respect for the things she cares for. Plants and trees, especially. Like Ilúvatar, Yavanna is not being spiteful. She is just pointing out the natural result of her husband not working in harmony with her. As with the forces of nature, and the shaping of Arda, and the Lamps, and the Trees, the Valar are always at their best when they cooperate with one another.

Yavanna is not exactly thrilled with her husband. She sees that Aulë is glad of the final result and points out how fortunate he is to be shown Ilúvatar’s mercy. She also points out that because he kept his project from her, his Dwarves will lack the proper respect for the things she cares for. Plants and trees, especially. Like Ilúvatar, Yavanna is not being spiteful. She is just pointing out the natural result of her husband not working in harmony with her. As with the forces of nature, and the shaping of Arda, and the Lamps, and the Trees, the Valar are always at their best when they cooperate with one another.

“Many a tree shall feel the bite of their iron without pity,” Yavanna says, wanting him to at least feel bad about it.

But Aulë doesn’t leave it at that, nor does he apologize. He says that when the Children of Ilúvatar do come, they, too, will have power over her works. It’s not just the Dwarves—Men and Elves will chop wood and eat plants, as well. They’ll hunt and kill animals. And of course this strikes a nerve with Yavanna, making her defensive.

Understandably, perhaps. Without permission, Aulë had designed creatures with hands, strong arms, and opposable thumbs, creatures who can make and swing axes! They can take what they want, and defend what they have. How fair is that?

But it also shows how naïve Yavanna is—indeed, how naïve all the Valar can be at times—concerning the big picture. She is forgetting that all the works of the Ainur, the whole shaping of Arda, had been for the Children of Ilúvatar, after all. That’s why they’d signed up to come down, to prepare and make the world ready for new beings. Arda itself is the habitation that Ilúvatar supplied for their coming. And Yavanna, at least in this moment, seems to have lost sight of this. But I think it’s worth noticing that she is not demanding; she’s just anxious. Where her husband broke the rules and only apologized after the fact, Yavanna gives her ideas more forethought. She is not possessive over what she wants for her world of plants and animals. She seeks permission up front to improve the plan. She is not prideful.

I especially like how Shawn Marchese, one of the hosts of the outstanding Prancing Pony Podcast, puts it in their episode about this very chapter.

In a larger sense, I think pride would have been to throw a Melkor-like temper tantrum…to march into Ilúvatar’s office and demand an audience. But she doesn’t. She goes to Manwë, and she says, “Look, I’m not happy about this. I love the things that I’ve subcreated and I know that sometimes the Children of Ilúvatar are going to wield dominion with bad intent.”

Yavanna asks Manwë if her husband is right. “Shall nothing that I have devised be free from the dominion of others?” she asks, pointing out that at least animals can run or fight when threatened, but plants can’t even do that. Especially the trees! Why does no one ever think of the trees?! Is no one on their side? She adds:

Long in the growing, swift shall they be in the felling, and unless they pay toll with fruit upon bough little mourned in their passing….Would that the trees might speak on behalf of all things that have roots, and punish those that wrong them!

Intrigued, Manwë shows that while he may be knowledgeable, he is not all-knowing. Despite perceiving the mind of Ilúvatar better than any other, some things from the vision even he had missed. Yavanna points out to him that even during in the Music, she had imagined the trees themselves singing to the sky, and she had woven that into her own song. Wasn’t that worth something?

So Manwë excuses himself, has a sort of Ilúvatar-induced reverie to think on it, then comes back to her. He tells her, essentially, that she needn’t have worried, that Ilúvatar has already accounted for her desire, and that when the Children of Ilúvatar appear so too will “the thought of Yavanna.” Which sounds rather vague, but Manwë explains that this will manifest as “spirits from afar,” and that said spirits will inhabit both animals and plants.

For example, from Manwë’s own part in the Music combined with Yavanna’s, there will thus come creatures “with wings like the wind.” More than mere beasts, these will be spirits in bird form and they will dwell in the mountains. That’s right, the Eagles we know and love (and unfairly expect too much of) will be coming, too!

But Manwë goes on, saying that in the forests “shall walk the Shepherds of the Trees.” BAM! Ents! Elated by this, Yavanna returns to her husband and snarkily points out that his Dwarves had better watch themselves, for “there shall walk a power in the forests whose wrath they will arouse at their peril.” And you just know she put a tone in that. Probably made a face, too. A you’ll-be-sorry look. Don’t mess with Yavanna.

Aulë is still kind of a grump about it, though. His rejoinder—the very last sentence in the chapter, which you really just need to go and read and enjoy—sounds a bit smug, and maybe he just wants to have the last word in their quarrel. But to me, Aulë and Yavanna simply sound like old souls who’ve been together, and in love, a very long time. These two helped shape and enrich the Earth itself; plants and minerals are essential to life and the food chain. Like Manwë and Varda, they clearly have made wonderful things together, and are each increased by the other’s presence.

Even so, this little spat of theirs, this moment of distrust on Aulë’s part and anxiety on Yavanna’s, certainly will have its echoes in later days. Perhaps a more familiar example comes also from The Lord of the Rings, when Legolas’s new Ent friend invites him to bring any Elf he wants to come see Fangorn forest at some future date.

‘The friend I speak of is not an Elf,’ said Legolas; ‘I mean Gimli, Glóin’s son here.’ Gimli bowed low, and the axe slipped from his belt and clattered on the ground.

‘Hoom, hm! Ah now,’ said Treebeard, looking dark-eyed at him ‘A dwarf and an axe-bearer! Hoom! I have good will to Elves; but you ask much.’

In the next installment, we’ll finally see the much-ballyhooed Children of Ilúvatar arrive, sleepy- and starry-eyed, in “Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor.”

“Spoiler” Alert: Errr….Melkor is going to become a captive somehow? Damn you, chapter titles!

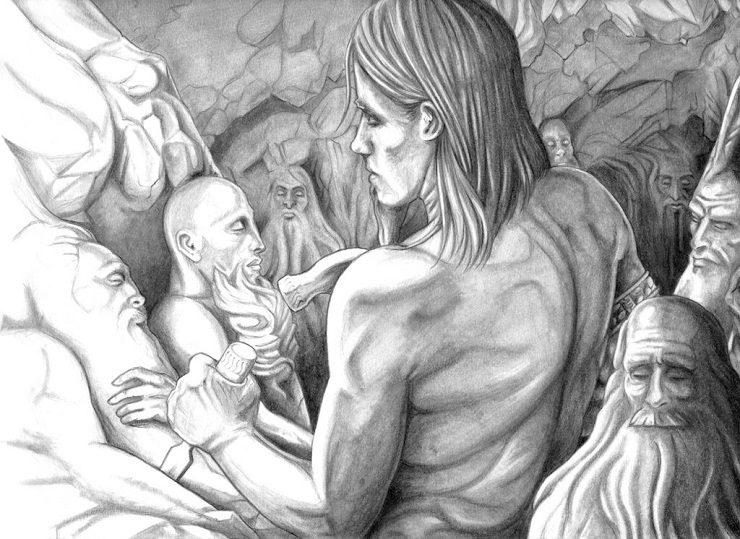

Top image: “Ents and Huorns” by Gonzalo Kenny

Jeff LaSala is ready for when his son someday asks him the awkward but inevitable question, “Dad, where do Dwarves come from?” He also wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, some cyberpunk stories, and some RPG books. And now works for Tor Books.

I’ve always loved Aule’s comeback while hammering away in his forge. It’s the Circle of Life folks. A concept the eternity minded Valar seen to have problems with.

@1: Aww, I was hoping to make people go and look that up for themselves. :)

But yes, it’s a good one.

I did have to look it up, and I’ve edited the quote out of my post.

So Dwarves and Elves won’t get along, eh? Good thing the proper Children of Ilúvatar will never have irreconcilable conflicts.

*cough*

Though if they did, I suppose someone might name the big book of history about it.

Hah. Well, Elves and Dwarves are predisposed to have problems is all that means. I think The Silmarillion does a good job of showing how both Elves and Men get along, and then sometimes don’t. And in the end, the book focuses on notable exceptions to all topics. It doesn’t spend a lot of time on the good years, decades, and centuries where there is peace or those times when various peoples get along really well. No one would read those parts… Notice we don’t read about a single peasant farmer who just lives his life, grows his crops, and never has any trouble. Rather, we read about princes and kings, lords and villains, companions and monsters. :)

Not that I wouldn’t totally read about a peasant cobbler or a laborer or a seamstress if it was written by Tolkien.

I don’t think it is a coincidence that both Sauron and Curinir were originally Maiar of Aule (and the Balrogs too, maybe?). The fine line between wanting to create and wanting to create and dominate what you have created is the difference between Aule and Melkor (and the above mentioned Maiar). Melkor definitely spent quite a bit of time recruiting in Aule’s “territory” because Aule and Melkor have the same desire to create, it just goes past that point with Melkor to the desire to dominate his creations.

Aulë goes and invents a language—likely Arda’s first!—for the people he himself made?

This is a massive deal in this context. Speech and language are right at the heart of Middle Earth – unsurprising given what JRRT did for a day job – and the Elves’ own name for themselves is not the Elvish for “the people” or “the wise beings” or anything else, it’s “Quendi” – “the speakers”.

So Aule has really jumped the gun here, in the most significant area of all.

Of course Treebeard feels much more friendly towards Gimli when he learns the axe is for Orc necks not trees.

There are some who claim that the oldest language in Arda was Valarin, the language of the Valar and Maiar. Though again, if the primer is restricted to the contents of the published version of The Silmarillion, then Khuzdul (the language of the Dwarves) may well be the first language that was noted in the book.

rec.arts.books.tolkien’s ‘definitive Silmarillion e-text’ follows Aule’s rejoinder with “And lo, he slept that night upon the couch.”

@6, I agree with you. But it’s kind of interesting that the boss of crafting, Aulë, despite this infraction, never goes nearly as wrong as some of his underlings do. But as noted in the previous installment, I bet he had some awkward conversations with HR. :)

@7, totally.

@8, quite right. But I think it’s still worth noting that Treebeard doesn’t necessarily have “good will towards” Dwarves at any starting point. The history is clearly a long one and contains many axes. An Elf who vouches for an axe-wielding Dwarf, though, gets a pass.

@9, right, in an earlier version there is talk of such languages. While the Valar probably have telepathy, who know they like Music and hearing, so it’s not like they wouldn’t have their own language. But still, they’re part of the management of Arda. Aulë went and made a language for one of the sentient races. Even the Elves are allowed to devise their own.

@10, but what a couch that would be!

The couch is better than another popular alternative.

Orome: “Aule, nice to see you, but what exactly are you doing in my backyard?”

Aule: “Oh, just spending some time with Huan, hope you don’t mind”

Orome: “I guess, sure, he is kind of a one Valar dog though, hey wait a second, why is your forge in Huan’s living quarters?”

Aule: So . . . Yavanna kind of ticked right now, so I am currently living in the doghouse”

Your ploy worked, I did in fact go back to check the last line of the chapter :)

Didn’t Yavanna notice that animals eat each other or plants? Doesn’t that bother her? Why can’t wolves or other predators protect Yavanna’s creations instead of becoming Melkor’s monsters?

Unlike the dwarves Yavanna’s animals can move on their own and seem to be awake before the elves. Do they not count because they can’t talk?

Aule forgot to make dwarf women. Did Illuvatar add them?

I don’t think Yavanna “noticed” that animals ate each other so much as devised them to. Whatever nature is, she’s part of it. I think animal vs. animal vs. plant is all part of her purview. But the Children are outside her control. Also, I think your average wolf is not Melkor’s. Wargs and werewolves would be his corruptions of these.

Whatever plants and animals were active before the Elves, and especially before Men, might have been rather different than we think. Remember, no sunlight yet. I bet there would be lots of crepuscular species thriving at this time.

We know that Aulë makes these seven Dwarf fathers, but that doesn’t mean he would stop there. When they are later awakened, there’s no reason not to think that Aulë finished his work and created the first Dwarf women, too. They certainly exist later.

When you showed the Valar discussing “Aulë did what?”, I imagined one of them saying, “And he made the males and females look exactly alike.”

Perhaps that could be explained by Aulë making only males, and Iluvatar turned some of them female so they could reproduce. Or maybe Aulë just wasn’t any good at carving women.

“But Yavanna dear, how could I imagine a female form when you weren’t there to model for me?”

I get, and agree with the fact that strife between dwarves and other races, tree, etc. “just is/was” and was not a punishment. What I wonder (nerd mind working) is how different would things have been if Aule had woven them into the music of the Ainur from the beginning, rather than in secret. Would the strife still have existed because he was weaving outside of the purview of the part he was given by Iluvatar? In other words, he asked for forgiveness rather than permission, but also did not try to hide it like he did, if any of this even makes since. (God im’a geek)

I believe Tolkien’s creation myth predates any modern notion of genetics. An updated version might well explain gender (i.e. sexual reproduction) as an invention of Yavanna (with evolution as a labor-saving device so her creations could adapt to Melkor’s sabotage of the world without constantly requiring direct intervention). This actually fits into the theme of creation encompassing and transcending discord…

But this would leave Valar “gender” as largely fashion choice rather than some intrinsic spiritual property. (While dwarven gender might just have been tacked on to the giant “moral agency for golems” compatibility update promised by Iluvatar.)

You didn’t mention that Ilúvatar not only forgave the making of the Dwarves but gave them souls (I forget the language used), i.e., made them more than automata.

Or that Aule’s offer to smash them recalls the sacrifice of Isaac.

I thought Orome found the Elves, soon after they awoke, and taught them to speak. Did the Author junk that idea?

@19, that’s part of the “incapable of independent action and free will” that I did mention. Although it’s basically referring to souls, Tolkien doesn’t use that word. He points out that the Dwarves will now have “a life of their own, and speak with their own voices.”

The Isaac parallel always seemed plain to me, but not to everyone, and since Tolkien never liked such strong comparisons being made, or anything like allegory, I didn’t want to go there. But correct, I didn’t mention that. I meant not to.

Oromë and the Elves, well, you’re getting ahead of me there. That’s in the next chapter. And remember, it isn’t Oromë who finds them first.

@19, 20

I don’t really buy the Isaac comparison for the following reasons:

a) Abraham was told to sacrifice Isaac; Aule volunteered to shmush the Dwarves

b) Abraham was given this as a test (and it is argued in portions of my faith community that the test was whether he would say “Heck no I won’t kill my kid, not even if You tell me to” and he failed this test); Aule was not being tested by Iluvatar as far as any way that I can read the text.

I don’t think anyone thinks it’s supposed to be the same thing, Dr. Thanatos.

That’s just it. The story of Aulë and the Dwarves calls to mind—at best—the Isaac sacrifice; it has tones of that. The willingness to destroy what one dears because a higher power seems to will it (and even that isn’t made clear). It does not parallel or neatly translate from there, absolutely not, and Tolkien wouldn’t care for that, either. There are so many echoes religious stories, myths, legends, and folklore throughout Tolkien but they’re never simply stolen and pasted in neatly. Aulë and the Dwarves bears the same resemblance to Isaac and Abraham as Maedhros chained to the side of a mountain (a few chapters from now) bears to Prometheus. Which is to say, some, but only so much.

Argh, no, Goodreads. Tolkien did not write that quote. The filmmakers wrote it. What Treebeard said in the book was: “I am not altogether on anybody’s side, because nobody is altogether on my side, if you understand me: nobody cares for the woods as I do, not even Elves nowadays.”

He didn’t think the hobbits were orcs at that point – if he did, he would have just stomped on them (as he was about to do before hearing their voices) and would definitely not have conversed with them like this. And I could be wrong, but I feel the twice-used “altogether” moderates the tone of the statement somewhat, offering the possibility of degree and change.

I’ve heard that Aule eventually made wives for six of the dwarf fathers, excluding Durin, but I don’t know the origin of that claim.

@23, argh, yes! That was the wrong designation. I’ve fixed it. I think I didn’t think twice because the sentiment was the same. But the “little Orcs” line definitely is a clue.

23, I think it was in some letters that were referenced in History of Middle-Earth, but I’m not sure, and there might have been attributions to Iltuvatar making them?

5, Ah, I believe that’s the great work of Cardassian literature, The Never-Ending Sacrifice.

@5: I personally prefer historical fiction about ordinary but interesting people who live out ordinary lives in another time and place without dramatically changing ythe he world — not about famous people and events. I enjoy fantasy like that, too, but it’s very hard to find.

Tolkien never explains why the suspicion and hostility between dwarves and ents exists. I can’t see that they chop trees down more than men or elves. They are basically into stone and metal, and a race of miners can presumably use coal rather than wood for fuel. OTOH, is there coal in middle earth? If not, forging quality steel will require charcoal, which might explain things.

@5 As far as Tolkien writing ordinary pastoral lives — extraordinary things do happen to the protagonists of Farmer Giles of Ham and Smith of Wooton Major, but they are ordinary pastoral people at root, and (if I remember correctly) they basically go back to their lives when the extraordinary is done with them. (Contrast how, at the end of LotR, Middle-Earth and the Shire have been saved but Frodo cannot go back to his life, having been irrevocably changed by the experience.)

@27, I would be very surprised if Aule didn’t create coal to appease Yavanna.

“You see, Dear, my children will burn these black rocks instead of wood.”

“They’ll burn rocks?????!

“I promise!”

“What a dear husband I have!”

In The Hobbit, Gandalf tells the dwarves they can “go back to digging coal” if they don’t like Bilbo as the burglar he found to complete their 14-person expedition team. How the coal got there, given Middle-Earth’s geologic history, is another question. I’d be fine with A Vala Did It.

I’m really enjoying these articles written by you.

My particular bugbear about Yavanna being pleased with the creation of the Ents and her concerns about the destruction of trees is the way Manwë gets uppity with her for having the temerity to suggest that his Eagles should live in aforementioned trees.

”Nay,” he said,”only the trees of Aulë will be tall enough. In the mountains the Eagles of the King may house therein !”

I quite went off Manwë after that. Did he think Varda would get jealous? Or was it a bit of old fashioned Ainur sexism?

Or was it a bit of old fashioned Ainur sexism?

I’m rereading The Silmarillion for the nth time and very slowly as I hate it when I reach the end…….

Oh, I don’t know. The dialogue is sparse, so I try not to read between the lines too much (unless it’s to make a joke about it). :) I don’t think “Nay” is uppity, but I do think Manwë could definitely ave been nicer about it. For such a lofty Vala he’s actually very humble. I regard all the Valar as old friends who’ve been through so much together, so they can be candid enough to one another.

“Aulë, this place is a mess. For Eru’s sake, can you please move all your tools and workbenches somewhere else? Don’t you have your own workshop?”

It was just the way he did it though.”

Manwë rose also,and it seemed that he stood to such a height that his voice came down to Yavanna as from the paths of the winds.”

In the discussion of Aule’s justification of his creation to Illuvitar, I’m reminded of Piet Hein’s “Simply assisting God”:

@23 “I am not altogether on anybody’s side, because nobody is altogether on my side, if you understand me: “

I use this quote rather regularly in political discussions these days…