In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

There are many gateways into science fiction—books that are our first encounter with a world of limitless possibilities. And because we generally experience them when we are young and impressionable, these books have a lasting impact that can continue for a lifetime. In the late 20th Century, among the most common gateways to SF were the “juvenile” books of Robert A. Heinlein. The one that had the biggest impression on me opened with a boy collecting coupons from wrappers on bars of soap, which starts him on a journey that extends beyond our galaxy. Wearing his space suit like a knight of old would wear armor, young Clifford “Kip” Russell sets out on a quest that will ultimately become entangled with the fate of all mankind.

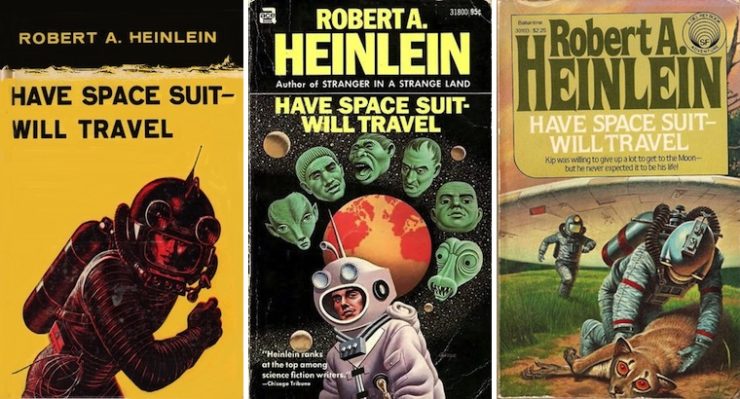

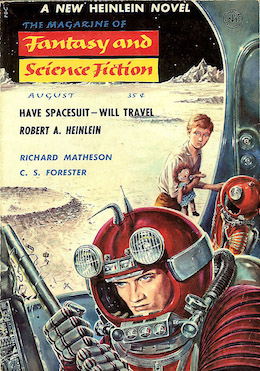

I can’t remember exactly what edition of Have Space Suit—Will Travel I read first; I suspect it was a library edition. Sometime thereafter, I bought a paperback copy of my own. I certainly didn’t pick it for its cover, which portrayed the hero in his space suit with the Earth behind him, and the faces of many of the other characters in shades of green around the globe, floating like severed heads in space. Jarringly, the artist left out the main female protagonist, perhaps thinking that boys would not want a book with a girl’s face on the cover (but regardless of the reason, at least we were spared the sight of her portrayed as a severed, greenish head). This cover suffers by comparison to the best cover that has ever graced the story: the painting on the cover of the serialized version in Fantasy and Science Fiction. There were two other Heinlein juveniles I read at about the same time: Tunnel in the Sky and Citizen of the Galaxy. I don’t remember a lot of details from most of the books I read at that age, but I clearly remember those three. The characters, the settings, and the action all stuck in my mind.

About the Author and His Juvenile Series

Robert Anson Heinlein (1907-1988) is among the most influential science fiction writers of the 20th Century. He was widely known both within and outside the science fiction community. His stories appeared not only in magazines like Astounding, Fantasy and Science Fiction and Galaxy, but in mainstream publications like the Saturday Evening Post. He co-wrote the script for George Pal’s movie Destination Moon.

In 1947, Heinlein sold the novel Rocket Ship Galileo to Charles Scribner’s Sons, a firm interested in publishing a series of juvenile science fiction novels targeted at young boys. This started a series of a dozen novels that appeared from 1947 to 1958, and after Rocket Ship Galileo came Space Cadet, Red Planet, Farmer in the Sky, Between Planets, The Rolling Stones, Starman Jones, The Star Beast, Tunnel in the Sky, Time for the Stars, Citizen of the Galaxy, and Have Space Suit—Will Travel. The books were all very popular, but Heinlein often argued with the publisher regarding suitable subject matter for youngsters. His stories often put the young protagonists in very grown-up situations including wars, revolutions, and catastrophes. His thirteenth book for the series, Starship Troopers, with its portrayal of a harsh, militaristic society locked in total war, proved too much for Scribner’s (I reviewed the book here). Heinlein then sold it to another publisher, and never looked back. No longer fettered by the puritanical limits of the juvenile market, he went on to write some of his best work: Stranger in a Strange Land, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, and Glory Road. The novel Podkayne of Mars is sometimes considered a Heinlein juvenile, but it technically was a separate work that grew from a non-SF female character that Heinlein liked and put into an SF setting. It was published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons in 1963, after the Scribner’s run of novels had finished.

The juveniles are not set in Heinlein’s more rigid Future History, although there are certainly similarities throughout. In recent years, my son and I set out to read all the juveniles that we had missed, and I found that more often than not, the settings of the books were pretty grim. While Heinlein shows mankind spreading out into the Solar System and then to the stars beyond, he repeatedly espouses the Malthusian notion that human population would grow out of control until war or catastrophe intervened. He frequently portrays governments that grow ever more totalitarian, and suggests that only on the frontiers could individual freedom be found. There are also some interesting clues to his future works in these early books—the powers of the mysterious Martians of Red Planet, for example, bear a striking resemblance to those later portrayed in Stranger in a Strange Land.

The social settings of the juveniles also can be jarring. The clichéd families, with the father serving as breadwinner and ruler of the household and the mother portrayed as obedient, passive, and nurturing, can set modern teeth on edge. While the male protagonists are all clearly beyond puberty, they display an indifference to females more appropriate to a boy in the pre-puberty latent phase of development. I wonder if this was something imposed on Heinlein by the publisher, as his own opinions in these areas were far more liberal.

The juveniles, however, excel in making the future seem believable, and are populated by characters the reader can identify with. And to a young reader, the grim challenges the protagonists faced in the books were the stuff of excitement. The books offered a view of how young people could face even the most daunting of challenges and overcome them. They offered a model of self-reliance and empowerment for the reader. It is no wonder they are remembered long after “safer” youth-oriented entertainment has been forgotten.

Have Space Suit—Will Travel

When we first meet Kip, he has just decided to go to the Moon. While mankind has established stations in orbit and on the moon, this is easier said than done. Kip, the son of an eccentric genius, is a senior in Centerville High School who works as a soda jerk at the local pharmacy (the assumption that there would still be soda jerks in drug stores in the future is one of Heinlein’s rare failures of vision). Kip has limited prospects of attending a first-rate college and knows that few people, even those at the top of their fields, get the opportunity to visit the Moon. So he decides on a novel method of achieving his goal: a soap slogan contest that offers the winner a free trip to the Moon. He begins to collect wrappers for the contest and draws mockery from local bully Ace Quiggle.

In the end, Kip does not win the contest, but he does win another prize: a surplus but functional space suit. Kip, a lifelong tinkerer, is fascinated by the suit, and soon decides to restore it to working condition. The description of the suit could have easily become a lump of exposition in the hands of another author. But Heinlein shows us that experience through Kip’s eyes, and through the restoration of the suit’s functions we not only learn how the suit works, but we see the process as an adventure in and of itself.

After he has fully restored the suit, learned how to use it, and even named it (“Oscar”), Kip decides that keeping it doesn’t make sense, and decides to sell it to raise money for college. First, however, he goes out into the night to take it for one last spin around the nearby fields. He uses his radio to make a call using imaginary call signs, and is surprised when “Peewee” answers. In a coincidence of the type that can only be used sparingly in fiction, there is a young girl, Patricia Wynant Reisfeld, nicknamed Peewee, on the other end of the radio call, desperate for help. Two UFOs land in front of Kip, there is a battle, and when he awakens, he finds that he is a prisoner aboard one of the ships.

Peewee is daughter of a noted scientist and has been kidnapped by malevolent aliens (nicknamed the “Wormfaces” by Kip) aided by two renegade humans, who want to use her as leverage to influence her scientist father. An alien that Peewee calls the “Mother Thing” attempted to rescue her, but is now a prisoner herself. Kip soon finds that the ship has landed on the Moon and he has achieved his goal, albeit in a manner he never could have predicted. He and Peewee escape the room they are trapped in, discover their captors gone, and find the Mother Thing and their space suits. Kip makes room in his suit for the Mother Thing, and they begin a walk to the nearest human outpost, which in my mind ranks among one of the most gripping episodes in science fiction. The fact that this was written in the days when space suits and moon walks were only gleams of possibility in the eyes of engineers and scientists makes Heinlein’s achievement even more impressive. They deal with challenges like incompatible bayonet and screw-jointed gas bottles with adhesive tape and ingenuity. In the end, however, their efforts are in vain. They are recaptured, and then are taken to Pluto, the Wormfaces’ main base in the Solar System. On Pluto, Kip and Oscar will face challenges that make their moon walk seem like a walk in the park.

At this point, each subsequent stage of the book represents a jump to situations even more strange and wonderful than the last. Heinlein takes advantage of the story not being in a fixed future history to turn the place of mankind in the universe completely on its head. While science fiction often shows us strange and wonderful worlds, this is the first science fiction book I remember that left me disoriented and even dizzy from what I had read.

On Chivalry and Chauvinism

While I highly recommend introducing young readers to Have Space Suit—Will Travel, it should probably be presented along with a discussion of gender roles. As I mentioned above, the Heinlein juveniles often present pictures of gender roles that were becoming archaic even when the books were written. Kip’s passive mother, for example, is almost part of the background, rather than a character of her own. And while Peewee is portrayed as having agency to spare, there are often statements suggesting that such behavior is unseemly for a young girl. Kip, on the other hand, is depicted as an exemplar of what at the time were considered masculine virtues. While its setting is science fiction, Have Space Suit—Will Travel is also a meditation on the issue of chivalry, with Kip’s space suit symbolizing a suit of armor that he uses in a noble quest. When he meets Peewee, he immediately decides that he needs to take care of her, or die trying. And during the tale, he comes very near losing his life several times. In his head, Kip frequently muses on tales of knights and heroes, and it is obvious that he has internalized these tales. But in addition to internalizing the virtues of chivalry, he has also learned some troubling chauvinistic attitudes, and a few pages after committing himself to die for her, he is threatening Peewee with spanking. All of which raises a problem that many older tales present to modern readers: How do we separate the sexism that sees certain virtues and roles as distinctly male and female from the fact that those virtues still have value to our society? How do we apply principles like “women and children first” in a world where women fight in combat side by side with men?

We can and should still present stories such as Have Space Suit—Will Travel to young people. But then we need to talk about them, and discuss what concepts are still important, and what our society is trying to learn from and leave behind. Our authors of today have a challenge, as well. How can they portray the virtues of heroism and sacrifice without the baggage of sexism? One model I can think of is Ann Leckie’s Ancillary trilogy, which takes many tropes that are near and dear to me, such as chivalry, nobility, duty and honor, and strips them away from their connection to gender (and even from a connection to a specific biological form). The result is like a breath of fresh air, and the protagonist, Breq, stands among some of the most admirable characters I have ever encountered. We need to give the Kips and Peewees of the future new models for the positive traits we need, without the baggage of past attitudes.

Final Thoughts

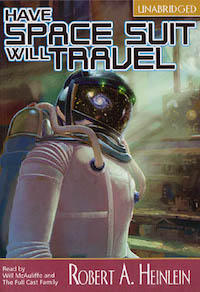

Before I end the discussion, I must mention the way in which I most recently experienced the story of Have Spacesuit—Will Travel, which is by listening to a full cast reading from Full Cast Audio. A full cast reading is partway between an audio drama which tells the story through dialogue and sound effects, and a straight reading of the book. Each speaking part is given a different actor, which helps draw you into the story, but the presence of a narrator keeps the experience closer to that of reading the original book. Bruce Coville and the team at Full Cast Audio have produced all the Heinlein juveniles in this format, and I highly recommend it as a way to experience the stories.

Before I end the discussion, I must mention the way in which I most recently experienced the story of Have Spacesuit—Will Travel, which is by listening to a full cast reading from Full Cast Audio. A full cast reading is partway between an audio drama which tells the story through dialogue and sound effects, and a straight reading of the book. Each speaking part is given a different actor, which helps draw you into the story, but the presence of a narrator keeps the experience closer to that of reading the original book. Bruce Coville and the team at Full Cast Audio have produced all the Heinlein juveniles in this format, and I highly recommend it as a way to experience the stories.

Have Spacesuit—Will Travel will always remain one of my favorite books. It starts out rooted in a world that seems so ordinary, and in the relatively mundane issue of space suit engineering, but moves on to more and more exotic locales, and finally to exploring concepts of what it means to be human and the nature of civilization. It is a ride that has rarely been duplicated in all of literature.

And now, as always, it is your turn to give your thoughts. What did you think about Have Spacesuit—Will Travel, or Heinlein’s other juveniles? And what are your thoughts on the place of chivalry in a changing world?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

“The assumption that there would still be soda jerks in drug stores in the future is one of Heinlein’s rare failures of vision.”

You mean, apart from most of the technology, the projection of 50’s gender and family roles into the future, the whole Malthusian thing…. That was an odd statement.

Darn it, the Full Cast Audio version of the audiobook isn’t available any more :(

1, maybe in the sense of being a failure to come up with anything remotely interesting, even if it turned out wrong. It is a bit underwhelming to not even have him serve SPACE COLA the TASTE THAT BLOWS YOU OUT OF THIS WORLD! as it were.

The other stuff, sure, Heinlein was wrong, but at least he had some vision for it!

50’s Heinlein is my favourite era of his work and Have Space Suit-Will Travel is a fine entry in his Scribner’s series: it would most likely be one of my top ten Heinlein novels. However, I read it in a rather later edition than Alan’s 1971 paperback, so for me the images it conjures have the retrofuturistic charm of a Norman Rockwell painting of an Earthrise.

The beauty of chivalry in a changing world is that it is unchanging because, outside of Malory and his peers, it never was.

Somehow I managed to totally miss the chauvinism but then I usually did. Heinlein was born and raised in a different era, I make allowances.

@1 Point taken. We may look up to Heinlein as the “Dean of Science Fiction,” but to use the word ‘rare’ was to give him more credit than is due. When you look at his work from the perspective of when it was written, his extrapolations were quite bold, but with the benefit of hindsight, the flaws are more obvious.

@2 Those Full Cast Audios are hard to find. Some titles are only available in older multi-disk versions, while a few are available in newer CD-ROM versions; I don’t know if any Audible versions exist. I do know that a lot were sold in library editions, so you may want to check your local library.

@@.-@ You are right in pointing out that the “Age of Chivalry” never lived up to its billing. I suppose it is like a Platonic ideal that we strive for but never achieve.

I know exactly which edition of Have Spacesuit I first read — it was an old hardcover, the yellow one on the left in the picture above, which I checked out of the public library (repeatedly) because while Dad had a bunch of Heinlein juvenile paperbacks (the Ace editions, as the center photo), this wasn’t one of them.

I was very happy in August of this year to go back to my hometown, go to the public library (not the one I grew up with; they built a very nice, new one and tore down the old one) and find that exact same yellow-jacketed copy of Have Spacesuit, Will Travel still on the library shelf 40 years later. (It was one of two books that I found where I’m almost certain it was literally the same copy I had checked out in my childhood; the other being one of C.S. Forester’s Hornblower omnibus volumes.)

I’d been reading SF & fantasy pretty much as long as I could read, but Heinlein was one of my major gateway drugs — the formative moment being spending an entire afternoon in the summer after 2nd grade reading Red Planet in pretty much one sitting.

We don’t. Children, perhaps, but there’s no reason to keep the “women” part of that maxim unless you think that women are somehow weaker or more in need of protection than men are.

My copy has the weird cat-like alien on it.

@8, I hate to tell you this but women are, as a general rule, physically weaker than men. Let’s not ignore objective reality shall we? Weapons can level the field granted and women have some physical advantages of their own but the difference is real and relevant.

I think it was my entry into science fiction. But I almost didn’t read it. The title was intentionally corny, and I despised corny (probably because I was so literal at the time that I couldn’t enjoy tongue-in-cheek). But, as I recall, my older cousin was reading it and recommended it, so I grudgingly agreed to start it. Ha! Then I couldn’t put it down, and I searched out all the Heinlein juveniles my library had on its shelves. Enjoyed them all.

Eventually I worked my way up to Stranger in a Strange Land, and learned to grok a blade of grass. I was never bored again.

I’m fond of Have Spacesuit Will Travel. But what’s going to put a kid off a book more than a ‘serious discussion of gender roles’? Save it for the adults in the blogs. It’s pointless anyway, since before you blink, the kid’s going to halfway through The Hunger Games and the problem will solve itself.

Caretakers and children first? If the goal really is the preservation of the next generation in a crisis, I’d think those best prepared and equipped to care for them, whoever that may be, would be the priority. The hard part comes in when people outside the situation feel the need to define who those are.

Spacesuit was probably my least favorite of the Heinlein juveniles – for whatever reason, it didn’t grab me at all. On the other hand, I read and re-read Red Planet and The Rolling Stones into pieces and I give them a lot of credit for making me a sci-fi reader. Trying very hard to get my son to read Red Planet now, too.

What I always found the hardest part of Heinlein’s gender roles (and what I expect will be the hardest thing about discussing them with my kids when they start to read his work), is that the women and girls *aren’t* entirely stereotypical and passive. While staying within the gender norms & assumptions of his time, Heinlein made relatively “strong” characters. It’s easy to discuss how the girl who has to stay home & help her mother clean reflects problematic societal assumptions & roles. It’s harder to explain how to woman who does the calculations for space navigation & can chase the pirates off single-handedly (Ok, I don’t think the latter happens in his book, but it’s in line with the characters), but defers to her husband for everything & gets indulged by him in turn, is also reflecting those same problems.

I would hand this book to my son (or daughter) without reservation or annotation.* If authors today wrote more books like this (and The Hobbit and the Narnia books), I would actually read YA!

I agree with you completely, Alan, about the space walk. It is the perfect example of how taking the science seriously can ratchet up the narrative tension and be immensely satisfying, even for someone as scientifically illiterate.

*Ok, maybe I couldn’t let the Malthusian nonsense pass without comment. Especially since people who should know better still spout that garbage.

@13 If you are trying to preserve not only the next generation but the reproductive capacity of the present generation women and children first makes sense.

@14. Like I said, another time other ways. Think of it as historical.

I ascribed many of the quibbles on gender roles to Kip’s viewpoint and the pub date. Kip is a teenager, hence the world is monochromatic and he is the center of the universe. Have Spacesuit Will Travel was published in 1958. The way all types of equality were portrayed or discussed was much different. For the two or the three main characters in the book to be “female” was a big deal. That neither of the “females” really needed rescuing by the big, strong male, but in truth “rescued” him is something that many people miss.

There’s a line in there somewhere about Kip’s dad marrying his best student. So Kip’s mom probably isn’t as passive as she’s painted. Teenagers, in general, are notoriously bad observers of their parents’ lives if it does not directly affect them.

Soda jerks by whatever job title are making a comeback in some places. Maybe not at your friendly corner drug store, but you can get a handmade cherry phosphate, green river, or other fountain specialties in many coffee shops, diners, and other eateries. (and often get an entertainment experience watching your drink or dessert being created.)

Keep in mind that Heinlein was writing in the 1950s and primarily for a young-male audience. Guys back then did not want a lot of romance subplots in their adventure stories.

And the only human female we see for almost all of the story is Peewee, who is maybe eleven years old. Having Kip perving on her would doom the book even now, and 100 times more back then.

Why does the presence of women have to mean romance?

20, It’s one of the more hackneyed “laws” of drama, apparently men and women can’t interact without sex being on the table. Unless they’re related, but sometimes not even not then.

Whether you’re commenting on the original post, the work under discussion, or the viewpoints of other commenters, please keep criticisms constructive in tone and avoid disparaging and dismissive comments.

Recovering from a bonk on the head Kit finds himself looking at a skinny kid in jeans. The rag doll suggests girl but still…

Kip: “Um, are you a boy or a girl”

Pewee: “I’ll make you regret that remark. I may be undersized now but I expect to be quite a dish in four or five years. You’ll probably beg me for every dance!”

Later safe at Mother Thing’s place Kip looks at a happy and relaxed Pewee modelling her skin tight new spacesuit and reflects that maybe she’s right about being a looker in a few years. He also thinks that she’s currently built like two sticks.

This was my first SF. I don’t know why I picked it out at the library in 1974, but that was it: from then on I was always going to the shelves with the rocket stickers on the spines.

Most of the story has faded from memory, but I’ve never forgotten the walk across the moon, when Kip tells Peewee “Drink some water, not too much” — and finds out her suit doesn’t have a water bottle. An early moment of courage in fiction for me.

The image of a plucky girl in a spacesuit, very competent for her age but nevertheless in over her head, now makes me think of Tiptree’s “The Only Neat Thing to Do”, which is another exploration story worthy of this reread series.

This open question is quite orthogonal to the alleged topic but I would be interested to hear recommendations for SFF audio stories. (I’m familiar with the fits and phases of Hitchhiker’s but not much else.)

Small quibble: Kip’s threat to spank Peewee wasn’t gender chauvinism. It was the standard response of a 1950s and earlier caregiver to a petulant child… and as I recall, Peewee was being particularly petulant at that point in the story.

Lord, has it really been 30 years since I last read Spacesuit? I’ll have to fix that. Oh, hey, Amazon has it. Bought for my kindle.

Was his reaction jarring to modern tastes in child rearing? Sure, but for when it was written, it was spot on.

Mr. Brown…

RAH died in 1988, not 1980. Might want to fix that.

Andy (VE #692)

25, well, I can’t help but recommend Alien Voices if you want some of that.

@27: Fixed! Thanks.

I don’t think I ever said that the attitude toward gender roles displayed in the Heinlein juveniles weren’t typical for his time; my point is that some of those attitudes are not appropriate for our times, and better left in our past. There are a lot of great books from the past that I think should be given to children to read, and this is one of them; but many of them should also be accompanied by some discussion. Although, from discussions I’ve had with my granddaughter, who read Podkayne of Mars last year, you might also find that the kids are way ahead of you, and well prepared to deal with works that present archaic ideas.

@25 Here is a link to an article I wrote on the Star Wars audio dramas, which are extremely well done: https://www.tor.com/2015/12/16/sounds-of-star-wars-the-audio-dramas/. I also like many of the BBC audio dramas, including Hitchhiker’s Guide, and Neil Gaiman works like Stardust and Neverwhere. Big Finish does a good job on Doctor Who adventures, and a lot of other properties. And if you go back to older sources, there are lots of old SF radio dramas from America that are available, from shows like X Minus One, which featured many of the most popular authors from the mid 1950s.

@27 Typo, pure and simple. You are correct.

The idea of “women and children first” is predicated on the view that a woman’s only real “value” to society is as a bearer of children. Although it has ceased to be a woman’s “only” value, the idea still has relevance since a woman getting pregnant is the only way you get more members of society. That said, I think it should be rephrased as “pregnant women and mothers with young children first.” In a life threatening disaster, those are the individuals I would be focusing on protecting/helping from the standpoint of children with their whole lives and potential contributions to society ahead of them, and the people most motivated to protect them — their mothers/parents. The farther along in her pregnancy a woman is, the more physically ungainly she will be and the more motility assistance she would need. Also, young children would be least likely to know how to react in a dangerous situation and it is their mothers/parents who would be most likely to be able to get them to cooperate with protective/rescue efforts. For the mothers to look after their children, and the rest of us (i.e., the able bodied of both sexes) to concern ourselves with protecting the group as a whole, getting to safety and assisting with rescue efforts seems a fair trade off. It also satisfies the biological imperative of preserving the ability to create more members of a species, which can be a powerful group unifier in life-threatening situations. I’m a woman, btw, and all things being equal, I can look after myself.

My first Heinlein was an excerpt from the beginning of “The Star Beast”, in which Lummox (the main character’s alien pet) gets out of the yard and goes on a destructive spree through the town in search of his chum. I remember there was a discussion question (this was in an old reading book) pointing out the casual use of the term “sidewalk”, which the monster brings to a stop because he is too big. This whole bit really stuck with me, and when I happened to find the actual book and started reading it, and got to that point, I got so excited!

Notable in this one is that the main character’s girlfriend has basically divorced from her parents (I forget the term used in the book) and lives independently.

I’ve listened to several of Shannon Hale’s books on Full Cast Audio, from the library, and highly recommend it. It was an interesting experience because I am a very fast reader, and with an audiobook I can’t rush ahead to find out what happens, I have to wait just as excruciatingly as the characters… Now when I do read those books, I still get that feeling. Really neat.

That was slidewalk, not sidwalk – as in a conveyer belt. Darn autocorrect!

It’s kind of interesting to have “women and children first” deeply baked into books so deeply concerned with the coming Malthusian catastrophe. Possibly optimizing our reproductive capacity might not be what we really need?

Interesting how long people ignored the demographic transition, as it seems to be called now — turns out every society has ways of controlling fertility and reproductive rate, it’s just easier and safer with modern technology. People were living in places with drastically changed birth rates and apparently not noticing.

The idea of “women and children first” is predicated on the view that a woman’s only real “value” to society is as a bearer of children.

Not really, no. It’s not “women of childbearing age and children first”, after all. You think that when the Titanic went down there were men going “Nah, throw her in the sea! She’s menopausal! Take me instead, I have years of fertility ahead of me!” For that matter, if it’s all about reproduction, why bother saving male children?

It’s about the idea that it’s the duty of the strong to protect the weak. Which was interpreted, in those days, as women, children and the elderly.

The Paris metro used to have a great notice above the seats by the door:

I’m sure I read Have Spacesuit, Will Travel more than any other of Heinlein’s YA fiction. I grew up in an environment where except for the local teachers, almost nobody had gone to college and I certainly didn’t know anybody with a science or engineering degree. HSWT introduced me to the idea of the relentless pursuit of becoming a college educated scientist/engineer and RAH’s namedropping of some science and engineering schools served as my introduction to them. I would later go on to attend one and become the first member of my family to graduate from college (BS/MS/PhD physics). We may not have teenage soda jerks any more but there are plenty of fast food joints and coffee shops with teenagers working behind the counter. Maybe the next kid you encounter asking “Would you like fries with that?” is mulling over the question of how they are going to the stars.

35, unfortunately, the Titanic is a bad example, since the failures in that situation included poor operations in general (the lifeboats were under capacity), and insufficient provisioning, it was a grade-A foul-up. And you can be sure, there were arguments that some healthy men were necessary on the lifeboats, to keep them afloat.

However, the sign doesn’t mention the sick and ill. What if I have a really bad cold? Is it wrong for a person to sit, when they’re at risk of collapse? I mean, sure, you could argue that I shouldn’t be out in public, but how else am I to get to the doctor?

Man, I am so not ready for immortality.

36, you’re scaring me you know. Very deeply.

I think what struck me the most when I first read this as a teenager, and what has stuck with me now, is the “trial” scene at the end. It was a shock to realize that even though Kip and Peewee had effectively stopped the invasion and domination of earth, and extermination of humanity by the “Wormfaces,” that Earth still wasn’t “safe.” They still had to “prove” that the Earth was worth saving, to a vast and powerful alien council that could destroy the planet in an instant. Had any other “juvenile” SF novel up until that point had a concept of such existential horror as a planet being “rotated” away from its star? Then and now, the image is terrifying–without warning, the Sun disappears, and the world will inexorably freeze to absolute zero in the darkness, with no hope of escape.. And Kip’s artlessly eloquent defense, his example of Earth’s cultural beauty–what does he choose as an unconsciously a propos example? That quotation from “The Tempest,” Prospero’s speech beginning, “Our revels now our ended…” I still get choked up thinking about it.

38, Certainly a frightening event, though not without precedent, but is the real horror not putting of the trial itself?

Well, like the age of chivalry, the “women and child first” too seems to be a bit of a literary myth:

women-and-children-first-is-a-maritime-disaster-myth-its-really-every-man-for-himself

@38 I hadn’t talked about the trial, because I like to avoid spoilers for those who might be reading about the book for the first time, but yes, it was a very powerful scene, and had an impression on me for years. I think that one of the factors that might have saved humanity is Kip and Peewee’s request to be returned to Earth to share the fate of their families.

@40 I think that is an awfully small sample size. While there are some disasters where poor leadership allowed chaos, there are also many cases where disaster brought out the better angels of human nature. For example: http://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Women-Children-First/

@30, I’m very fond of Podkayne of Mars. Poddy is portrayed as highly competent both intellectually and socially. She is obviously as qualified as any male pilot candidate and the fact that her sex counts against her is clearly depicted as unfair. Her choices boil down to banging her head against a glass ceiling or achieving her goal by switching to a specialty where her gender will be seen as an asset.

Heinlein also mentions sexism against women in professions like engineering and astrogation in The Rolling Stones. Once again it is clearly shown to be unfair. Heinlein tried not to be sexist but his early training and ingrained cultural assumptions betrayed him.

One of the things I had to discuss with my granddaughter about Podkayne of Mars was the ending. Heinlein originally wanted Poddy to die but the editors wanted her to live. So when Baen republished the book a few years ago, they had a vote and essay contest, and published it in paperback with the preferred ending and essays arguing pros and cons for the decision. Her father and I had both entered the essay contest, and had our essays published; her grandpa wanted Poddy to live, while her dad argued that Poddy should have died as Heinlein originally intended.

43, now we’re all stuck with Schroedinger’s Poddy! Congratulations in getting your essays published!

Killing Poddy was a mistake. It made the whole book about Clarke not her. I disliked that very much.

45, so is that a vote for excising the climax entirely? I can see that.

Not at all. I have no problem with Poddy’s critical injuries causing her kid brother to rethink things and change for the better. But I feel killing her changes the focus of the whole book.

@24: “The Only Neat Thing to Do” is my favourite late Tiptree story and I agree that it merits a revisit.

Re SF Audio: Of those mentioned, the BBC adaptations seem relevant to my interests and easily accessible. I am somewhat ambivalent about their Dangerous Visions strand but today I enjoyed hearing their more expansive version of Northern Lights and intend to listen to the rest of the trilogy before reading La Belle Sauvage. (I think they also occasionally broadcast Big Finish stories on 4 Extra…)

Re Podkayne of Mars: I have that Baen edition: I recall thinking that the book was a lesser effort and that I preferred the ending from the original book publication.

My friend’s mother gave me a copy of Have Spacesuit… when I was ten. I remember enjoying it and finding the relationship with the mother thing to be simultaneously gross and amazing. Have been meaning to revisit for about 35 years now…

I first read Have Space Suit, Will Travel when I was quite young, and I remember it as the first book I read with a young, intelligent female character in a positive role, which really caught my attention. Stories I’d read before typically had female characters as background (if there were any at all) or as characters that always needed to be saved, never doing the saving. So my memory of HSSWT has been as an exception to then common chauvinism.

After reading this article, I decided to reread the book to see how I’d view it now. I agree that Kip’s mother should have had a bigger role in the story, though I still don’t see much I’d want changed today in Peewee’s portrayal. On one hand, Peewee was shown as an intelligent and heroic figure. On the other hand, she was an eleven year old that went around telling strangers that she was smarter than they were, corrected their grammar, and made the foolhardy decision to go off with strange men in a sketchy situation and got herself kidnapped. Yes, there were comments in the story about her character flaws, but I don’t think most of them would have changed much if Peewee had been male.

Kip wasn’t sure if she was a boy or girl initially, but he definitely saw her as a young child that he wanted to protect (I see nothing wrong with that attitude). Remember that Kip was about to go to college (so several years older) and much larger. He didn’t talk down to Peewee, and quickly recognized her intelligence, bravery and competence. In fact, when he talked to her father, he pointed out that she was smarter than he was and had saved his life repeatedly. He didn’t boast about the times he had done the saving.

The story showed Kip and Peewee as a team, depending on each other for survival and support. Neither would have survived without the other. Both had flaws, but that just made them more interesting characters. When I first read it (and was a bit younger than Peewee’s age), I remember thinking how much I’d like to meet someone like her, character flaws and all. I consider Peewee to be an amazing character.

@51 You and others raise a good point. While by today’s standards, the gender attitudes of the book leave lots to be desired, by the standards of the day they were actually somewhat progressive.

@1: “You mean, apart from most of the technology, the projection of 50’s gender and family roles into the future, the whole Malthusian thing…. That was an odd statement.”

Really. His technology is generally amazing. See, for instance, The Door Into Summer which is eerily accurate. 50’s gender and family roles are still far too present, even though most families have to have two bread-winners these days. And I’m not convinced that Malthus wasn’t right.

Heinlein was writing before the green revolution fastly increased agricultural production. Kip actually says at the end that just because he didn’t talk about his mother as much didn’t mean she wasn’t important. In Edith Stone Heinlein tries to depict a woman who is quiet and seemingly unassertive yet is the actual head of the family. He may have been trying for the same in this book.

Hi

Bit late to the party but for what it is worth. I began reading Heinlein’s juveniles in my public school library in the 1960’s. I loved them and they and some of his short stories remain my favourite works by Heinlein. I can no longer read The Moon is a Harsh Mistress and the Door into Summer and I don’t think I read any of his novels after Stranger in a Strange Land. I did not read Have Spacesuit then I am not sure why so I read it as an adult. And I loved it for someone my age maybe there is an element of nostalgia but I don’t think we had soda jerks even then. I reread it recently and the part I liked the most was when Kip describes seeing the Great Nebula of Andromeda and the Greater Magellanic Clouds from a new and closer viewpoint. That brought back that old sense of wonder we hear so much about from old planet bound codgers like me.

Happy Reading

Guy

@7:

It suddenly seemed to me that a defect of electronic books is that they never necessarily will look old: and old-looking and -smelling book clews us in that some of its attitudes may also be long in the tooth. Keeping e-books’ typography, covers, and spellings constant may help, as well as woud forbearing adding-in (say) multimedia and V.R. bits as those become standard.

More generally:

Barry Malzberg said (I think at the 2008 Readercon) Heinlein’s problem was that he understood perfectly how America worked—in 1945.

And: Growing-up male in the late 1960s and early 1970s, I’m afraid the sexism didn’t grate—but the 1950s small town clichés did. Oh, wait: ‘Marrying my best student.’ sounded creepy…and the last time I read it, having heard a little more about Sex World by then, though not having landed mtself, I suspected that R.A.H. might have a ‘thing’ for spanking.

I read Have Spacesuit first as a kid in the 1960s, and it is still one of the Heinleins I periodically reread (along with Citizen of the Galaxy).Heinlein did try to get past the gender thing, at least for aliens, as Kip realizes that the Mother Thing is probably not a female or a mother; it’s too bad the Professor Thing is cast with male pronouns, but Heinlein just had the two for animate beings.