It’s December, which means that in many places, even here in largely sunny Florida, the scent of gingerbread is in the air. Or in our coffee. Or in our fudge (this is kinda weird). Or safely locked into our candles.

Which made me think, naturally, of the fairy tale of “The Gingerbread Boy.”

The version best known in the United States originally appeared in St. Nicholas Magazine in 1875—just two years after the magazine’s founding. Designed to take advantage of a growing interest in “suitable” children’s fiction, the magazine was headed by Mary Mapes Dodge, best known for her 1865 novel Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates. That novel showed Dodge’s sneaking interest in folklore and St. Nicholas, with entire chapters focused on describing how the Dutch celebrated St. Nicholas’ Day. Interesting sidenote: Dodge had never visited the Netherlands in her life, but she had read books, and she had Dutch neighbors, and worked to make the novel as accurate as possible.

The success of that novel helped bring her to the attention of publishing company Scribner & Company, who wanted a distinguished editor associated with children’s books to head their new magazine. It helped, too, that Dodge had some additional writing and magazine experience. Dodge liked the idea, and set to work on creating a high quality children’s magazine. It was a popular and critical success, instrumental in inspiring several later 20th century writers ranging from Edna St. Vincent Millay, who liked the poems, to William Faulkner, who liked the pictures.

The success of that novel helped bring her to the attention of publishing company Scribner & Company, who wanted a distinguished editor associated with children’s books to head their new magazine. It helped, too, that Dodge had some additional writing and magazine experience. Dodge liked the idea, and set to work on creating a high quality children’s magazine. It was a popular and critical success, instrumental in inspiring several later 20th century writers ranging from Edna St. Vincent Millay, who liked the poems, to William Faulkner, who liked the pictures.

These days, St. Nicholas Magazine is probably best known for publishing the earliest versions of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Little Lord Fauntleroy and The Little Princess, but at the time, it was known not just for its serialized children’s novels, but for its short stories and verses—including “The Gingerbread Man.”

The opening lines root the story deeply in the past, noting that this is “a story that somebody’s great-great grandmother told a little girl so many years ago.” Maybe. Two elderly people live in the woods. Like most childless elderly people in fairy tales, they long for a child, and apparently have no friends with surplus grandchildren that they can borrow for the fun of having a kid around for a few hours without the burden of actually having to care for a child.

Their desire reaches the point to where the old woman decides to bake a little gingerbread boy. I will leave everyone to ponder what type of old woman, exactly, would try to create a child that she can later eat, or even a child substitute, or what, exactly, this says about the attitude of some parents towards their children (yay, we can live off them in our old age! Maybe eat them if things get really desperate!) and instead just note that this bit of baking does not exactly go the way holiday baking generally does (that is, with some either excellent or questionable goodies, plus a lot of time spent licking the spoon and the bowl—an essential part of December baking. Don’t judge me.) Instead, presumably thanks to the woman’s longing for a child, the little gingerbread boy comes alive in the oven.

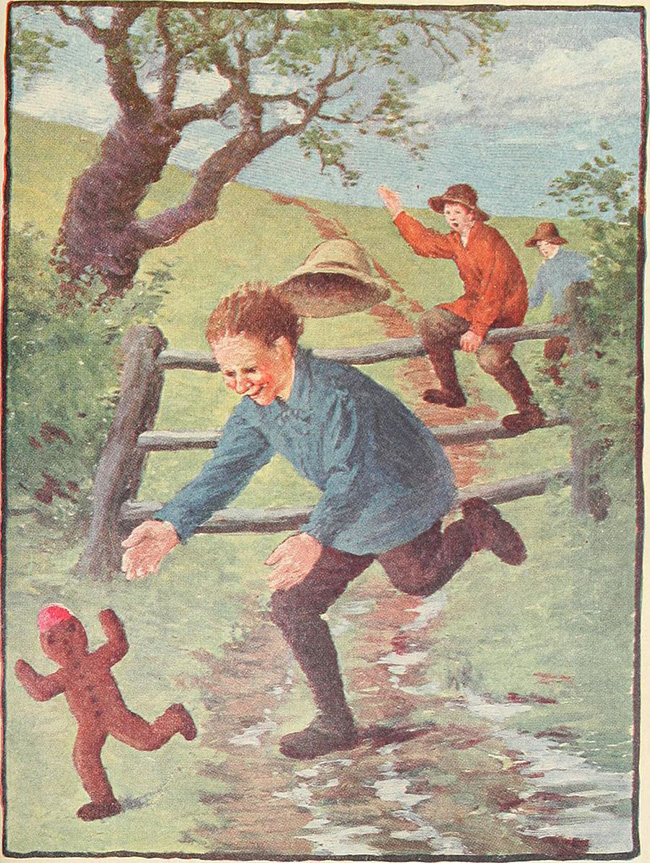

Sensibly enough, the kid immediately decides that he doesn’t particularly want to be eaten, and takes off. And sure, I suppose we could argue that they would have treated them as their own dear son, but, let’s face it, many own, dear sons don’t fare all that well in fairy tales, and to repeat my earlier point: most people only bake things that they plan to eat. So I’m with the gingerbread boy up until this point. Unfortunately, his success at fleeing them makes him more than a little bit arrogant, and when he meets the next set of people, he taunts them, practically begging them to chase him.

At this point I have a lot of questions, including, but not limited to: how is this kid speaking, and where exactly did he learn language and rhyme? Was the old woman reciting poetry as she kneaded the dough and cut out the gingerbread shape? Are his little gingerbread lungs just an air pocket in the dough? The story doesn’t have time for that, since the taunted people—a group of threshers—are already chasing him, either because they are hungry (the immediate gratification storyline) or because they immediately realized that a talking gingerbread boy provides a lot of financial opportunities (the greed storyline.) They are not very fast threshers. Nor are the mowers, the cow, and the pig who follow. The gingerbread boy cheerily repeats that he can run away from them, he can, he can.

But—in a clearly intended illustration of pride going before a fall, a fox sees him—and, well, he can’t. He can’t. The boy is a quarter gone, then half gone, then all gone.

GULP.

I can’t help but think that gingerbread is probably not on the recommended diet of foxes, but then again, this is rather unusual gingerbread, and maybe all of that running around allowed the gingerbread boy to develop some protein in his muscles, adding a bit of nutrition for the fox. And I think we can all agree that even foxes deserve a treat from time to time. At the same time, I can’t help but notice that a cow also took an interest—an animal not exactly known for a carnivorous diet.

The story was clearly designed to be read out loud, with its amusing rhymes and repetitions, and not to be taken too seriously, for all of its underlying horror. But that underlying horror also has a rather stern moral message: running away from parents, even parents who presumably want to eat you alive, is dangerous and can lead to you getting completely eaten up by a fox, ending your extremely short life, and ensuring that you yourself will never get to eat gingerbread again. Terrifying. Message received, short story.

The St. Nicholas version lacks a byline, making it entirely possible that this version was written by Mary Mapes Dodge, who had a habit of inserting folktales into her works without clarifying where, exactly, she had heard the original tale. (Dodge was also responsible for spreading the American story of the little Dutch boy who put his finger into the dike, another folktale she did not originate.) She also may have written the poem. The concept, however, was hardly original: The general idea of baked goods running away from their bakers is a relatively common one in folklore—quite possibly as a way to account for baked goods that were inexplicably “missing”—that is, illicitly consumed, or burnt/destroyed during the baking process. In some years, and in some places, this could be quite serious. Better to claim that the pancake had simply run off—pancakes, after all, do that sort of thing—instead of facing accusations of theft.

Other versions seem to nod at the reality that some baked goods do have a tendency to disappear if, say, left in places frequented by Very Good Dogs. And if the dogs want to claim that the baked goods just happened to jump right into the mouths of those Very Good Dogs—a claim that would get more or more elaborate in later retellings—well, who I am to doubt the words of Very Good Dogs?

And in still other cases, these might simply have been comforting tales to tell young children disappointed to find out that the family budget couldn’t cover holiday treats that year. It’s not so much that the family couldn’t afford them, but that the baked goods just didn’t feel like getting eaten. But no, they weren’t wasted—in nearly every story, the runaway cakes and cookies end up getting consumed by someone, often a clever fox.

But these stories of talking and fleeing baked goods may not have just been aimed at children, or dogs. It’s probably not too much of a reach to see these sorts of tales as loose allegories of another very real situation: lower class workers laboring over baking goods that are later snatched away from them by non-workers. Or just as cautionary tales to remind bakers to keep an eye on the oven at all times. This latest tip also brought to you by the Great British Baking Show which if nothing else has taught us that it is regrettably easy to underbake or overbake something even when—or especially when—the judges are watching.

Moral and economic motifs aside, children loved the story. Later illustrators were also intrigued, creating several picture versions, some using the same words as the St. Nicholas story (which had the advantage of passing into the public domain not all that long afterwards), some altering the text and rhymes slightly. Still, it’s entirely possible that you may have missed the tale, either as a child or as a grown-up munching on gingerbread. In which case, let me leave you with this reminder: watch your holiday baked goods very carefully this year. They might just run away with you.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.