Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

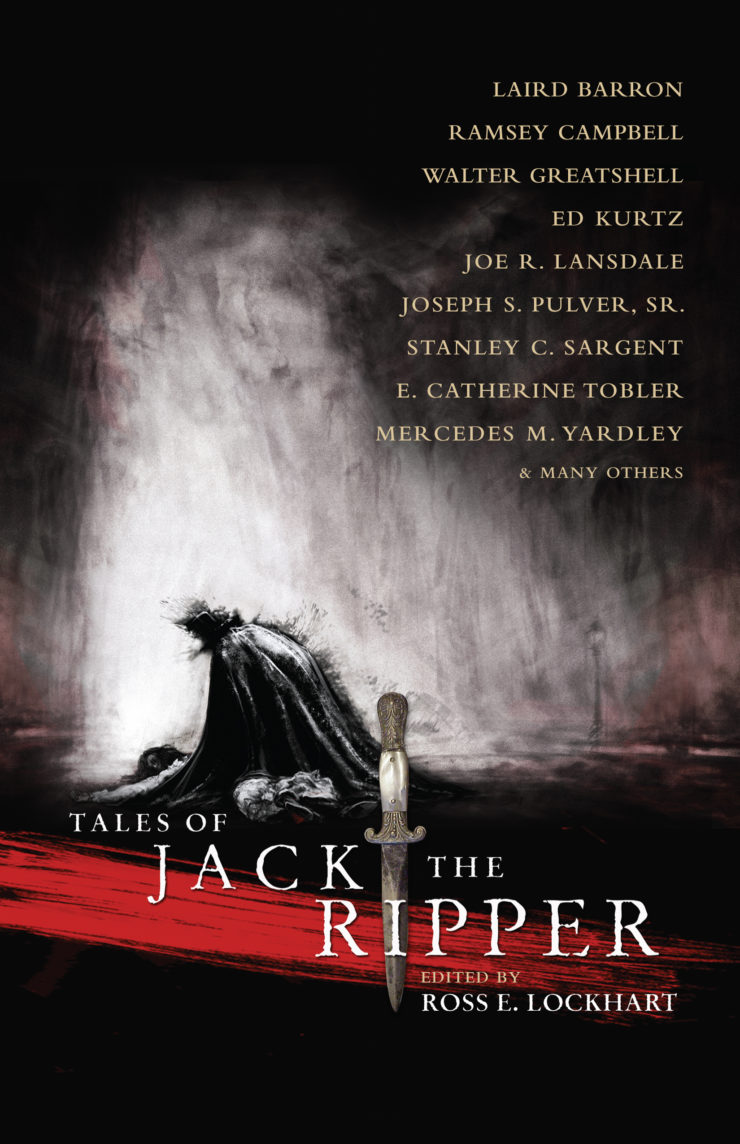

Today we’re looking at T. E. Grau’s “The Truffle Pig,” first published 2013 in Ross E. Lockhart’s Tales of Jack the Ripper anthology. Spoilers ahead.

“I know myself as the 42nd of my kind, and the success of my art is the last barrier that keeps us from falling into the soundless crush of the eternal abyss.”

Summary

Our narrator is many things: a ghost, a whisper, the shadow of a thing that casts none. Oh, and also saboteur, tracker, and killer of men and women. Especially women. Reviled, hated, yet the only thing that stands between our world and its fall into “the soundless crush of the eternal abyss.”

Narrator would kill every one of them if it were possible, but the order’s learned to keep its numbers low, hence secret. In the 7th century, “drunk on hubris and…righteousness,” it attempted eradication of the enemy and was nearly eradicated itself. Now it follows them like a “bloodline curse,” from the great Western Desert of Egypt to the red hill country of southern France to the Pictish Highlands above the Antonine Wall. The Romans never built barriers without a reason. Now their bulwarks crumble, while the underhill lurkers they feared still await the return of their Masters.

The narrator’s prey follow the Dark Man who three and a half millennia ago strode out of an Egypt screaming under His plagues. Multitudes went with Him, to secretly keep alive the Elder Ways and sow anarchy in preparation for His advent.

Narrator’s order releases one member at a time to follow the Dark Man’s spoor. Chaos begs for order, and order lives to stabilize chaos. What forces make it so? No one knows. “The reality presumed by the rational mind is just an onion skin surrounding the deeper mysteries spiraling at the core.” Order members train in secret fighting arts and “a mental foundation grounded in the philosophies of dead moons.” Then they learn anatomy and vivisection, because human flesh is their modern battlefield, the excision of corruption their victory for both the infected and the world at large.

The order didn’t foresee that narrator’s recent London assignment would draw such avid local attention, then ignite national scandal and global sensation. People were used to brutal murder in the old days. They didn’t make a fetish of it, to be shrieked in the papers and discussed with horrified titillation in aristocratic drawing rooms. Now narrator had to slake “the insatiable thirst of pen and populace” (and Scotland Yard) with rumors of conspiracy — monsters walk among them!

Yes, but not the monsters they imagined. Not all the Dark Man’s followers were human. The human, however, hired East End prostitutes for clandestine orgies that were actually mating rituals meant to spread a fungal stain through London’s population, and beyond. For didn’t many foreign visitors take advantage of the city’s fabled brothels? By the light of black candles and smoking braziers, spores would be deposited in drugged bodies. Then wounds would be washed, bustles retied, and the human hosts released to share their deadly contagion. Worse, they would act as incubators for tiny parasites that would mature to polyps and then something more, aspiring to grow as tall as their fathers, the “intelligent bacteria from far off Yuggoth.”

Narrator’s job was to cut those “bad bits” out, wherever the “vagaries of the copulation” may have left them, behind a cheekbone, in a womb, in intestines, in the heart. Of course, the police had misinterpreted mutilated corpses as the work of a madman, but they had understood and fled once more, this time across the Atlantic, to disembark at Arkham en route to Chicago.

In Chicago, soon, a World’s Fair will draw human flies from every country on the planet, a feast of potential hosts. Until then, different as they may seem from the 17th century Pilgrims that left England before them, they too are an exodus of the faithful.

Narrator, their curse, follows aboard the same ship. A slip on the icy gangplank could have ended in a dip in black seawater except for a sailor’s quick grab. “Watch yourself, miss,” he says.

Narrator allows the sailor to escort her to the pier. He natters on about the Ripper. Not that a fine lady like herself needs to worry, but “a bird’s gotta keep her eyes open back home. Never know if Jack’s headed your way.”

Unable to ignore such an opening, narrator purrs back: “What if he’s headed your way?”

Her dart sends the sailor scurrying back aboard his ship.

“The fear has spread, as the game continues.” Narrator called herself Jack in London, but that was just the latest of her masks. Her name is the Truffle Pig, “hard trained to root out the fungus. I am your protector, the 42nd of my kind. I was yours truly, and I will be again soon.

“So next, Chicago.”

What’s Cyclopean: Narrator turns a beautiful, bitter phrase: Victorian London offers “days of lace and buttermilk,” where “death was marched into sitting rooms and made to dance.” Nyarlathotep is “inscrutable even to his followers, who bow low to the riddles.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Narrator describes the rumors of conspiracy with which she covers her tracks: “Princes, Freemasons, palace doctors. Occulted journalists and Polish Jews.” Then she suggests, obliquely, that Nyarlathotep led the Jewish Exodus from Egypt (or maybe was Pharaoh—or both).

Mythos Making: The Mi-Go are out there on the edges of the story, six steps ahead, implanting their unfortunate victims with parasitic spore. Meanwhile, Narrator’s ship lands smack in the middle of Lovecraft County (Arkham, Kingsport, and Martin’s Beach off the starboard bow) on her way to the Chicago World’s Fair.

Libronomicon: Nyarlathotep’s “legacy of plague” is “co-opted by various holy books.”

Madness Takes Its Toll: Unlike the Mi-Go, narrator seems to have little interest in what’s going on in other people’s heads, madness or otherwise.

Anne’s Commentary

The Dark Man is known by countless other names. I’m fondest of Nyarlathotep for the way it trips off the tongue like the hiccough of whippoorwills in the blithe summer twilight. The Truffle Pig boasts a name for each of her masks. In this week’s story, she’s Jack the Ripper, aka the Whitechapel Murderer, aka Leather Apron, aka Case Never Solved. The suspect list remains long even today, ranging from the Queen’s naughty grandson Albert Victor, through celebrities like Lewis Carroll and Arthur Conan Doyle, through physicians reputable and not so much, down to a choice handful of the home-grown and foreign poor who called London’s East End home.

To pair the Mythos with arguably the most infamous crime spree in history, an obvious choice would be to make “Jack” into a Cthulhu/Tsathoggua/Name-Your-Deity cult whose leader wisely decides that for ritual fodder, it’s easier to procure prostitutes than virgins, and besides, Great Old Ones and Outer Gods don’t notice any difference. The narrator-hero would then be some “broad-minded Scotland Yardie” who, assisted by a tweedy academic with access to the British Museum Necronomicon, would uncover the cult, spearhead its eradication, and convince his superiors the matter must be covered up, for the sake of the country’s, nay, the world’s sanity!

Grau makes a much more interesting choice. He opts out of a clear hero-villain dichotomy and instead makes both protagonist and antagonists complicit in the murders. The Dark Man’s followers use human females to incubate Mi-Go spore. Presumably, the incubators will die horribly when the matured polyps erupt into independent life. So, that’s a bad outcome for the woman. Really bad. So is being slashed to death and minutely dissected. I bet you’d be hard put to find a dollymop or drab who’d thank the Truffle Pig for cleansing them of the fungal taint via vivisection, even if she did explain how, by bleeding out on the cobblestones, Dollymop Drab was doing her own small but crucial part to Save the Planet.

Grau’s second interesting choice, I’m thinking, is to model his Truffle Pig’s “Jack” on a suspect called Jill the Ripper. Conan Doyle supposed Jack might have worn woman’s clothing to approach his victims and move under less suspicion. But the notion that the killer might actually be a woman was floated early in police investigations. If so, the investigators concluded, she was most likely a midwife. Why? In 1939, in Jack the Ripper: A New Theory, William Stewart uses questions to elicit the reasons: Who could leave her house at night without arousing suspicion from her household or people she might meet? Who could walk the streets in blood-stained clothing without arousing suspicion? Who would have knowledge and skill to commit the anatomical mutilations of the Ripper? Who, if found by a woman’s body, could have any alibi for being there?

Yes to all four, a midwife. Midwives, of course, deliver babies. In the 19th century, and before, they also administered abortifacients and performed abortions. How fitting, if Jack the Ripper were really Jill the Ripper, and Jill were a midwife, and the midwife were also an abortionist, because the Truffle Pig is exactly that – an abortionist of Mi-Go spore and polyps!

Fatality rates for the mother in clandestine abortions tend high. Sounds like Truffle’s fatalities are 100 percent. Something in her may struggle to care – I see a glimmer of that. But her ancient order’s training is stronger than any sympathy or compassion on an individual level. She must care for the planet, for its survival as is, evolved to suit us, HUMANKIND, in caps. She must fight for Order, for opposed to it is Chaos and the Dark Man. She must fight though she knows that Chaos and Order coexist in a balance ordained by forces no one understands or dares to question. Might as well harden up, then. Call the doomed prostitutes or other victims spares, mules, spider sacks to be sucked dry, poor drabs, whores, collateral damage. Get cold, girl. If you’re stuck on the skin of the onion, don’t worry about the deeper mysteries spiraling to the core. Some mysteries might involve how the Mi-Go and the followers of the Dark Man and the Dark Man Himself believe they are the defenders of Order, humanity the sowers of Chaos. Too mind-blowing to contemplate.

You are Buffy (Truffie?) the Fungus Slayer, 42nd Slayer in your line, and relax. None of the Mi-Go look like Angel or Spike. You’ve got this.

Next, Chicago, is it? In plenty of time for the 1893 World’s Fair, or Columbian Exposition! That was some event, featuring exhibits from 46 nations on 600 acres of neoclassical grandeur. Twenty-seven million people visited over six months, so there must have been good hunting for the Mi-Go. As luck would have it, there was also a serial killer for our Truffle Pig to pin her gruesome handiwork on. That would be H. H. Holmes, who confessed to 27 murders, nine of which were confirmed. It’s said he may have murdered as many as 200 people! Certainly he aspired to that number, what with the hotel he built near the fair grounds. It was informally called the Murder Castle, for it featured soundproofed rooms, secret passages, and trapdoors to chutes that dropped to a basement full of acid vats, quicklime pits, and a crematorium.

Whoa, that sounds like the sort of lair Truffie might design….

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I think the time has come to admit that I’m allergic to mass murderers. I’m sorry, all you horrible people who enjoy cutting up your fellow human beings, it’s not you, it’s me. And it’s not the killing, it’s the monologuing.

Of course, this week’s narrator isn’t really a mass murderer, right? Not like Hamentaschen’s wanna-be purveyor of cosmic indifference—Truffle Pig has a mission. Saving the world from Nyarlathotep’s evil minions one surgically-vivisected prostitute at a time. Isn’t that worth a little monologuing?

Sure, I guess. Maybe. If Miss Pig didn’t sound so much like an ordinary mass murderer, with a convenient story about why her depredations are so important. Or possibly, if she’s being truthful about the “us” part, a cult of mass murderers, all convinced that their killings are necessary to the world’s survival. The Aztecs had the same deal going, as I recall. Without that constant stream of sacrifices the sun would go out—how dare you question that, just think of the risk if you’re wrong.

But we know, we Mythos readers, that the Mi-Go are really out there, not just a convenient excuse, right? And they really do serve Nyarlathotep, who really did come out of Egypt in ancient days and really does want to lead everyone into a Pit of Doom. Lovecraft’s dream told us so, after all.

I dunno. Miss Pig doesn’t seem to have a hell of a lot of sympathy for the people she’s supposedly saving. Let alone those she’s killing—even positing a perfectly reliable narrator, and the absolute necessity of cutting fetal Mi-Go out of helpless women, surely describing her victims as “random spares” isn’t a requirement of the job. And I have a… let’s call it an instinctive feeling of revulsion: when someone uses the word “miscegenation” with a straight face, I start questioning whether their view of reality is completely accurate. Or whether it’s reality they’re viewing at all.

All of which Grau doubtless intended—after all, the point of a monologue story is about half mood and half the puzzle of the narrator’s reliability. Many people adore this sort of thing—and if this is the sort of thing you like, you’ll probably like this story. It’s just that, inconveniently for a horror reviewer, I’ve started to build an immune reaction to the stream of narrative self-justification. My nose gets stuffy, my eyes itch, the nauseous sensation comes upon me that someone has cable news on in the background.

So what was I hoping for, last week, when Anne glossed this as “Jack the Ripper vs. the Mi-Go”? I have to admit, I was kind of hoping for Mi-Go detectives in Victorian London. There’s a natural conflict there, even without possible apocalypse-by-Mi-Go-spores. Say you’re a fungus looking for people who have lousy lives and might enjoy traveling the universe—but someone has started to kill the people you’re trying to recruit, and they seem to have no interest in the brain at all. They just leave it there to rot. Something must be done. Alternatively, surgically-trained Jack starts finding people who under their veneer of human skin are something else entirely, and then…

Back to the topic of unreliable narrators, what’s up with the Truffle Pig nomme de guerre? I get the obvious metaphor—she’s trained to sniff out something small and rare and important, and root it out. And the obvious joke, since truffles are, well, fungi. But truffles are also used for something. It follows that the Truffle Pig’s masters, referred to only obliquely, have some use for Mi-Go spores. Do we really want to know the details? I’m pretty fond of mushrooms, but as an eldritch delicacy these definitely sound like an acquired taste.

Next week, learn a few more things man was not meant to know in Algernon Blackwood’s “The Man Who Found Out.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.