The first indication I’d seen that I was in the right place was the little Ezio walking down the line of people waiting to enter the Schomburg. He could not have been more than eight years old, but his Assassin’s Creed outfit shaped itself perfectly around his small frame. Later that day, that little black Ezio would be joined by Nick Fury, Falcon, and Blade. Wonder Woman would make an appearance. As would a number of new heroes—black bounty hunters in space, animal whisperers, men and women with swords as big as them.

The 6th Annual Black Comic Book Festival—filled with kids who looked like me gawking at comic book covers featuring kids who looked like us, filled with books and art and gloriously fly merch, not to mention its Black Power exhibition on the second floor featuring a scopic look at the movement as it existed in the States and as it existed in the world—that festival is exactly the kind of place I would have once thought beyond imagination.

That festival, this current moment, are only the latest iterations of the wave of Afrofuturism washing into the mainstream. What is Afrofuturism? A literary movement? An aesthetic?

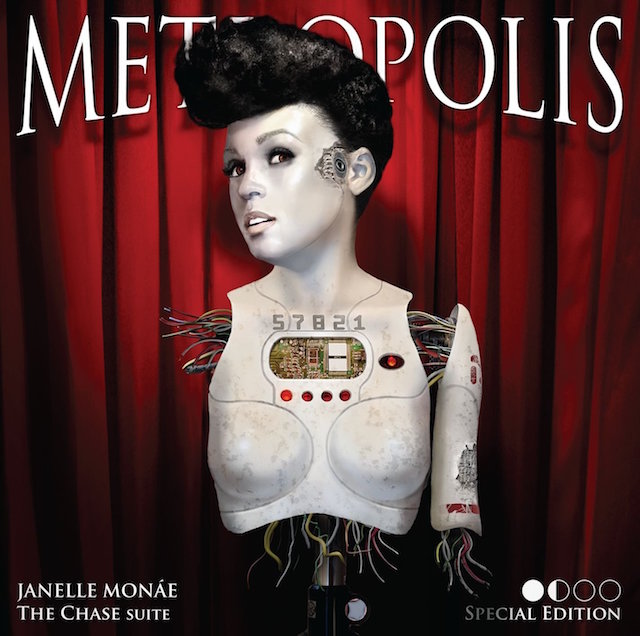

With the music of Janelle Monáe, the speculative fiction of Nnedi Okorafor, the synths of Sun Ra, we have a growing collection of artistry that sees a place for people of color in the future. In the fantastic. And the Black Panther movie is only the latest entry in the pantheon.

Afrofuturism is a Janus-faced endeavor. That past shimmers before us, mirage-like, as we cast our gaze forward. Squint hard enough and what do you see?

***

It’s usually some version of heaven.

In American churches, black Americans are the Israelites. The Egyptian overseer’s whip is the white slavemaster’s whip. Bondage carries the same intensity and interminability then as it does in the Black American narrative. A glorious nation built on the backs of those who were never meant to take part in its glory. If you want to build something magnificent in America, throw death and suffering at it. One hopes, in sharing a retributive God with the Old Testament’s Chosen People, that as Egypt crumbled, so too would the America that Blacks built. A better future is waiting for us. In photos that have been indelibly burned into the African-American memory, the slave’s back is to the camera, the whip-scars a spiderweb of third rails on a hunched back. American industry is written on that back. The history of an agrarian economy is written on that back. One imagines on the back of the Israelite a similar cartography and, in tracing its lines, one can discern the very geometry of the pyramids.

The incessancy of the suffering is also necessary for the narrative tuning fork to resonate. Enter the alchemic Negro Spiritual. A sonic reprieve in those moments of quiet when the business of building an empire has ceased, and, the sun setting, slaves gathered together beneath the shade of a tree or by a house in the slave quarters away from the mansion, and maybe an elder ministers to them from the Bible with some Scripture he has memorized and they join him in song, singing of what else but deliverance? Of a fiery chariot spiriting them into the sky. Fertilize that dream for a century, and that chariot becomes a spaceship.

***

Early in March of 2010, I attended a conference in Dakar that brought together Parliamentarians and the heads of electoral commissions of countries throughout West and Central Africa. Though I was an intern for the Carter Center at the time, I was given my own nameplate and place at the table. I’d been brought along, not only because of a project I’d been working on at the time for President Jimmy Carter, but because there was a deficit of translators at the conference. I was to bridge the linguistic gap between the Anglophone and Francophone participants. Accommodating the Lusophones would require a bit more ingenuity.

Unlike most discussions around the mechanics of nation-building—discussions that tend to operate at thirty-thousand feet in the air—our multilingual conversations and debates concerned the presence and number of international observers, the difficulties of establishing polling places in the more remote corners of a country, transport of ballots, security at polling stations, how to make the fairness and free-ness of elections a reality. Much like high-speed rail, a thing that begins as a science-fictional dream, the impetus for its creation is ultimately convenience—make the election of leaders and the living of life a little easier. Some countries were, indeed, even talking about electronic voting, which would engender an entirely separate batch of headaches, but which seemed part and parcel of the future. This is where we are going, these men and women were saying. President Carter, watch us build our chariot.

Dinner with my supervisor one night found us at an open-air restaurant. Nearly a decade has passed since that night, and I no longer remember what we ate or drank. But I do remember that one of the young men by our table, a friend to one of the servers, had defunct Blackberries hanging like ornaments from his necklace. They jangled, upside-down and blank-screened, and I sat, transfixed at the sight of a phone turned into ornament.

It looked…cool.

***

Much of Afrofuturism, like that chariot becoming a spaceship, involves—indeed is sometimes predicated upon—a reaching into the past. African-Americans have become the subject in the sentence. We’re no longer the aliens whose planet is terraformed without our consent, no longer the aliens whose genocide is the goal of the protagonists. No, we are the explorers. We pilot the spaceship. Afrofuturism can’t outrun the past. It carries it like weights around its ankles. Sun Ra’s electric keyboard had hard bop and cosmic jazz in its veins, but it reached back into ancient Egypt for its themes. The act of time-travel that frames the track “From Then Till Now” by Wu-Tang Clan affiliate Killah Priest similarly harkens back to that age of Kings and Queens:

Memory erases, from the slave ships

My princess, I used to spot her from a distance

Holding my infant, burning incense

The moment intent for her to step into my white tents

Now we step in precincts. For your ebony prince

The smell of frankincense, once treated like a Pharaoh

With royal apparel, anointed with myrrh and aloe

We used to wallow amongst the mallows

We had herd sheep and cattle, now we battle

American funk band Parliament, in their magnum opus, Mothership Connection, sends us into space. We take our street talk and our slang with us. Nothing but our present. With the erasure of national borders, it is a future that mirrors the erasure of the past. African-Americans, with histories systematically beaten and raped and sold into oblivion, must remake themselves with a blank slate. With the funk aesthetic draped over our shoulders like a gem-studded, floor-length fur coat, we walk freely into the future, a citizen of the universe.

Afrofuturism here is an answer to the question: what if the future happened to us?

Nisi Shawl’s masterpiece, Everfair, asks that question. What would Congo look like if it got steam-powered technology before its Belgian tormentors? The novel’s answer is kaleidoscopic and Tolstoyan in its capacity for compassion.

Rather than go back in time to kill future despots and ethnopolitical entrepreneurs, Afrofuturism pushes the button to rip through time and space and address one of the single greatest tragedies visited on people of this planet. That peculiar institution. The rending asunder and subsequent plunder of an entire continent.

Sometimes Afrofuturism feels like a wondrous re-centering where suddenly the plasma blaster is in my hands. I’m the one to make the decisions that ultimately save my crew. Tupac told us that he knows “it seems heaven-sent, but we ain’t ready to see a black President,” and there was a time when the prospect of a black person in the Oval Office did seem as science-fictional as a black person at the helm of the Starship Enterprise.

But, sometimes, when I look closer, I see a more ambitious political project. I see the pyramids being built. When Janelle Monáe brings the cyborg into Afrofuturist discourse, it is to make a statement about slavery and freedom and the female body. Her alter-ego, Cindi Mayweather, incites a rebellion to rescue the oppressed. Deus ex machina, except that God is black, and she is female.

So, one arrives at Nnedi Okorafor’s Binti trilogy and sees not only a little black girl embarking on an interplanetary odyssey and building a truce between warring races. One sees not only adventure and action and a little black girl doing cool things. One sees that the very act of centering a black girl in a story can be a radical political, paradigm-shifting act. In Dr. Okorafor’s Who Fears Death, young, impetuous Onyesonwu, a child of war herself, contains within herself immense power, a power to change the very world around her. And it is perhaps this affirmation that lies at the heart of so much Afrofuturism. We are empowered. We can drive the future. Watch us build it.

***

The miracle of transfiguration turns tragedy into glory, coal into diamond, and, in this latest cultural event—the film adaptation of the Marvel comic Black Panther—the activating agent is vibranium. An African territory is the recipient of this empyrean gift, and out of the soil rises the most glorious kingdom the world has ever seen.

Afrofuturism allows the imagination not only to cure the injury but to imagine a world where the knife blade of colonialism escapes the black body altogether. Wakanda grows—in the absence of plunder, in the absence of white avarice, in the absence of unadulterated capitalistic impulses married to race hatred—into a wonderland. A marvel of technological innovation. As though to say, this is what Africa would have become had you not spoiled it. Where science fiction of the more vanilla variety posits non-whites in a metaphorical other space—the strange thing is happening to us or we are the strangeness—Afrofuturism has us as both the strange thing and the strange thing’s object. Aliens land in Nigeria. Cindi Mayweather rescues us from the Great Divide. In Black Panther, both hero and antagonist share a hue. Love interest, spy, technological wunderkind, village elder…all the same color. Which isn’t to say that Afrofuturism trafficks in presents and futures devoid of white people. It is rather to say that, more than other branches in the genealogy of the genre, Afrofuturism is hyper-conscious of its context.

Rivers Solomon’s devastating and urgent debut novel An Unkindness of Ghosts brings slavery and Jim Crow into outer space. Sharecropping and the racial stratification of society don’t vanish if we turn Noah’s Ark into a generation ship. Afrofuturism knows that the future would not rid present oppressors of their pathologies. In our reality, algorithms help police departments target communities of color and deny parole and early release to prisoners from those very same communities. In our reality, Google Images will pair images of black people next to images of gorillas. In our reality, the future, as unevenly distributed as William Gibson once predicted, is racist. Afrofuturists know this more than most. The fiery chariot whisking us into the future still has the dirt of a poisoned past on its wheels.

***

The future is Africa.

A burst of speculative fiction from the continent is testament to the variety of truths embedded in that sentence. Industry and technology provide fertile soil for startups. Ingenuity fills the air that so many Africans breathe. (How else do you play Shadow of the Colossus on your PS4 uninterrupted when the National Electric Power Authority in Nigeria cannot be relied upon to keep the power running?) And the fiction increasingly speaks to the speculative possibilities on the continent. The imagination is ignited.

Lesley Nneka Arimah’s remarkable and brilliant short story collection, What It Means When A Man Falls From the Sky, tells of a woman who weaves a child out of hair, women hunted through the generations by the ghosts of war, and so many other dazzling characters and situations, infusing into the lives of non-whites the sensawunda that permeates the DNA of so much wonderful speculative fiction. A. Igoni Barrett’s novel Blackass imagines a young man in Lagos, on the morning of a job interview, turned into a white man, except for one particular spot on his body.

The fiction in every issue of Omenana Magazine, edited by writer Chinelo Onwualu, contemplates what the future looks like for Africans, and it seems as though the latest direction of the literary discipline bends back towards the continent. Recalling what it felt like when our animals talked and when our gods walked among us. The future reaching back into the past.

Afrofuturism has long concerned itself with counter-histories, the lion speaking in the hunter’s place. And now, we are seeing Afrofuturism contend with that central question again of what do we do when the future happens to us. Hacking. Enhancement and augmentation. Surveillance. Even post-human possibilities. Put those themes in the hands of a discipline one of whose weapons is hyperconsciousness of context, and the universe becomes quantum. A corner has been turned. Where before African-American and African discourse, dialogue, and aesthetic back-and-forth may have seemed like two ships passing in the dark, we are now close enough to touch. The Diaspora and the Continent may stand on opposite ends of the bridge, but they can see each other’s luminous smiles. Beyoncé’s short film, Lemonade, provides just one example of the seismic, paradigm-shifting spectacle that can be made of this union, of the dialogue that occurs when we find ourselves having upgraded finally from the telegram to the Blackberry to the beyond where the Blackberry is mere ornament.

Black Panther is another.

***

Born an American of Igbo parents, I’ve long felt an interloper in both worlds. To be a second generation Nigerian—a Naijamerican—is to kind of, sort of know why Tommy not having a job on the sitcom Martin is funny and to kind of, sort of be able to speak pidgin. It is also to know the entire Wu-Tang discography alongside the marvels of jollof rice. I sometimes envied the Nigerian-born I went to high school and college with. They had the accent. So many references to black culture in the ’80s and ’90s, I could only pretend to know. As a child, I felt too young to truly appreciate the genius of Chinua Achebe. And none of the science fiction and fantasy I read envisioned a future or an alternate history for me. None that I could find.

Yet, located within the history of Diasporic bodies is that original dislocation of the Middle Passage, Africans rendered as aliens, strangers in a strange land. Afrofuturism posits, among other things, a theory of homecoming.

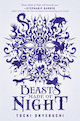

We recognize Wakanda. We’ve had Wakanda in us this entire time. The promise of unparalleled technological advancement, the great potency, the actualization of our boundless intelligence and ingenuity, the raw power in our hands and feet. Afrofuturism opens the door to N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy. It opens the door to Tomi Adeyemi’s upcoming Children of Blood and Bone. It opens the door to the Black Panther movie. Space is the place, as Sun Ra initially proclaimed. But outer space is also Africa where so much is possible, the future limitless.

It turns out that this may be where our fiery chariot was taking us.

Home.

Tochi Onyebuchi’s fiction has appeared in Panverse Three, Asimov’s Science Fiction, Obsidian, and Omenana Magazine. His non-fiction has appeared in Nowhere Magazine, the Oxford University Press blog, and the Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy, among other places. He holds a B.A. from Yale University, a M.F.A. from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, a J.D. from Columbia Law School, and a Masters degree in droit économique from L’institut d’études politiques. His debut young adult novel, Beasts Made of Night, was published by Razorbill in October. 2017. Its sequel, Crown of Thunder, will hit shelves in October 2018.

Tochi Onyebuchi’s fiction has appeared in Panverse Three, Asimov’s Science Fiction, Obsidian, and Omenana Magazine. His non-fiction has appeared in Nowhere Magazine, the Oxford University Press blog, and the Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy, among other places. He holds a B.A. from Yale University, a M.F.A. from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, a J.D. from Columbia Law School, and a Masters degree in droit économique from L’institut d’études politiques. His debut young adult novel, Beasts Made of Night, was published by Razorbill in October. 2017. Its sequel, Crown of Thunder, will hit shelves in October 2018.