Director Ramin Bahrani had a difficult choice ahead of him while adapting Ray Bradbury’s 1953 novel, Fahrenheit 451: make a faithful adaptation of the beloved book or update it for an audience closer to Guy Montag’s dystopia than Bradbury’s original vision.

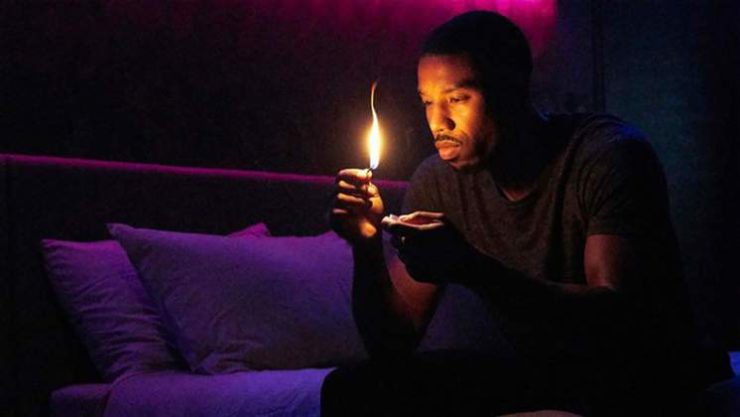

Watching the new HBO movie, it seems Bahrani tried his best to compromise, and the result is not going to ignite a lot of passion; let’s just say that Michael B. Jordan, fresh off his killer success in Black Panther, is not going to snap any retainers here.

Yet, not every update or revision is a bad choice.

Bradbury’s novel was far from perfect to begin with.

I somehow escaped high school and college without reading Fahrenheit 451. And most of my adult life, too. In fact, I only read it last week. So, I have no nostalgia for this book. I do, however, love Bradbury’s short fiction and his skill with prose. I dare you to read “The Foghorn” and not cry. Or not get creeped out by “The October Game” or “Heavy Set.”

I just couldn’t feel any spark of passion for Fahrenheit 451.

Guy Montag is such a 1950s idea of an everyman—his name is freaking Guy!—that it was pretty alienating to read in 2018. Guy’s pill-popping, TV addict wife Mildred is a dead-eyed shrew that Guy scorns and yells at for most of the book. His 17-year-old neighbor, Clarisse, is a fresh-faced ingenue whose abstract thinking and hit-and-run death leads Guy to revolt. Both women exist primarily to inspire action in a man. It’s outdated and ultimately unkind.

Worse, by book’s end, every single book but one Bradbury explicitly references in Fahrenheit 451 was written by a man. Usually a dead white man. Every book listed as “saved” by the resistance was written by a dead white man. You mean there are whole towns who have taken up the works of Bertrand Russell and not one person is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein?! No Hurston? Austen? Not one damn Brönte sister?! No Frederick Douglass or Langston Hughes? Bradbury’s book has an extremely narrow view of what qualifies as “Great Literature” and demonstrates the most sneering kind of fanboy gatekeeping as he rails against anti-intellectualism and the evils of television.

So, in that regard Fahrenheit 451, the movie, does a good job of not erasing women or people of color from all of human literature. Or from the film itself. But in its decision to be more inclusive and modern, it overcorrects and changes the original story so much that it just seems to extinguish any spark of meaning that might’ve tied it to Bradbury.

So, in that regard Fahrenheit 451, the movie, does a good job of not erasing women or people of color from all of human literature. Or from the film itself. But in its decision to be more inclusive and modern, it overcorrects and changes the original story so much that it just seems to extinguish any spark of meaning that might’ve tied it to Bradbury.

In a time when truths, much like Bradbury’s favorite books, are constantly under attack in politics, the media, and online, Fahrenheit 451 is strangely mild in its depictions of authoritarianism. When I first heard there would be an adaptation of the novel, I wondered not why this particular book, now, but how? It’s much more complicated to talk about freedom of information when the internet is here. Yet, you can’t have Fahrenheit 451 without firemen burning books, so the movie tries to update Bradbury’s dystopia by including Facebook Live-style streaming emojis to the firemen’s video broadcasts and some super-virus called OMNIS that will open people’s minds or something. It was never made clear.

We’ve seen better, smarter dystopias in Black Mirror.

Michael B. Jordan’s Guy sleepwalks through most of the movie, letting others tell him how he should feel, whether it’s a one-note Michael Shannon as his father-figure boss, Beatty, or his informant/crush, Clarisse. Very little of Guy’s largely beautifully-written inner monologues from the book survive, so viewers can’t really appreciate his widening understanding of his murky world or his self-determination. Clarisse is re-imagined as a Blade Runner background character with punky hair and still exists to inspire Guy to fight. She’s at least doing some fighting of her own, though her role in a wider resistance is just as muddled as the resistance itself.

Michael B. Jordan’s Guy sleepwalks through most of the movie, letting others tell him how he should feel, whether it’s a one-note Michael Shannon as his father-figure boss, Beatty, or his informant/crush, Clarisse. Very little of Guy’s largely beautifully-written inner monologues from the book survive, so viewers can’t really appreciate his widening understanding of his murky world or his self-determination. Clarisse is re-imagined as a Blade Runner background character with punky hair and still exists to inspire Guy to fight. She’s at least doing some fighting of her own, though her role in a wider resistance is just as muddled as the resistance itself.

Overall, the film explicitly states that humanity fell into this anti-intellectual dystopia because of apathy, but never offers characters or a believable world to inspire anything beyond that in viewers.

Theresa DeLucci is Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier. Reach her via raven, owl, or Twitter.