In Which the Son of Húrin Is Raised Among Elves, Goes Out to Seek His (Mis)fortune, and Becomes a Host of Household Names While At Least Trying to Not Wreck All of Beleriand

The fantastical yet tragic story that became Chapter 21, “Of Túrin Turambar,” is one that J.R.R. Tolkien had worked on in the earliest days of his created world, before there was a legendarium. I mean, the story’s outline spawned The Silmarillion itself. And because it’s such an important one and, well, a long one, I’m going to tackle it in two parts, as I did with Beren and Lúthien. I’ll mostly discuss the abridged version of the tale as it’s told in The Silmarillion (itself being an abridged account of what appears elsewhere).

And, look, it’s a grim one. This is not a fairy story with a happy ending featuring dive-bombing, eucatastrophic Eagles. It’s a goddamned Shakespearean tragedy where everyone—well, nearly everyone—dies at the end. There are dragons, suicides, manslaughters, elfslaughters, dwarfslaughters, and even a talking sword.

Túrin is the quintessential flawed hero of Tolkien’s works, the perfect foil to the Aragorns and Faramirs of the legendarium. He’s the one-man Exhibit A for why things aren’t always black and white in Middle-earth, as Tolkien’s critics are prone to libelously assert. So, let’s see Exhibit A.

Dramatis personæ of note:

- Húrin – Man, captive audience (of one)

- Morwen – Woman, Lady of Dor-lómin, war widow (effectively)

- Túrin – Man, hapless son of Húrin and Morwen

- Beleg Strongbow – Sinda, chief marchwarden of Doriath

- Mîm – penultimate Petty-Dwarf

- Gwindor – Noldo, Angband escapee

- Glaurung – Dragon boss, progenitor

Of Túrin Turambar

Let’s start with Elrond’s list again, the one he invokes in The Fellowship of the Ring when speaking to Frodo after the hobbit offers to take the One Ring on its quest for destruction:

But if you take it freely, I will say that your choice is right; and though all the mighty Elf-friends of old, Hador, and Húrin, and Túrin, and Beren himself were assembled together, your seat should be among them.

No matter what follows, Túrin (TOO-rin) is considered a hero and an Elf-friend. Sometimes good intentions and a few good deeds are enough to get you on that roster.

But newcomers to Túrin’s story should know that the 2007 novel The Children of Húrin tells it in full—a book which Christopher Tolkien pieced together from his father’s original poetic and prose. Originally it was simply the Tale of the Children of Húrin—or Narn i Hîn Húrin, as it is named in The Silmarillion—and it first showed up in fragments in Unfinished Tales, but the aforementioned novelization is a great read, even if it is very sad. And hey, the audiobook is read by Christopher Lee, if that sweetens the pot for anyone.

Now here’s a funny thing about Túrin: He’d have grown up hearing stories of the legendary Beren, the mortal Man who cut the Silmaril from the crown of Morgoth himself. And young Túrin would therefore have heard that over the course of his adventures, Beren earned for himself a couple of different names based on misfortunes. Three in total: Beren, Erchamion, and Camlost. Well in this story, Túrin’s all, “Only three, Beren? Hold my mead…”

Túrin aims to top that that number, and I’m going to categorize his story, as briefly as I can (i.e. not brief at all) with each of his names as he receives them.

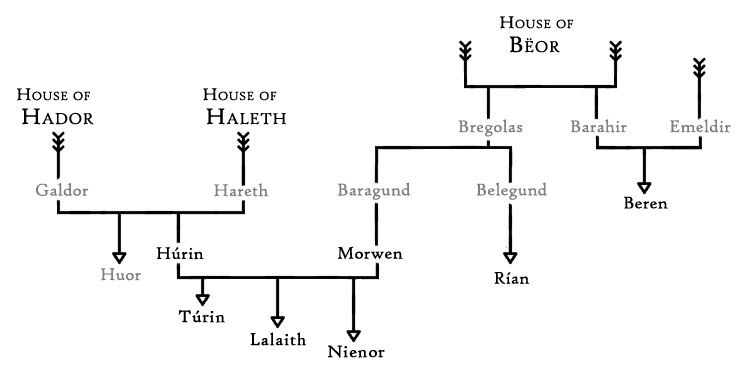

But before there was Túrin, there was Morwen, a proud daughter of the House of Bëor, first house of the Edain. In fact, Beren One-hand is a relative of hers. Her great-uncle was Beren’s dad, Barahir. Since Húrin’s own blood came from the chieftains of both the House of Hador and the House of Haleth, Morwen’s kids are the product of all three houses. It’s confusing, I know. So look here:

Morwen’s name means “dark maiden” in Sindarin, but she’s also given the Elven epithet of Eledhwen (EL-eth-when), which means Elfsheen. Having multiple names seems to be a family affectation. Back in Chapter 17, Tolkien gave us a spoiler: from Morwen would come Túrin, “the bane of Glaurung.” And considering that the father of all dragons has been a real nuisance in Beleriand lately—three times he’s come forth with fire and fury—it’s good to hear that his days are numbered.

While Morwen married Húrin, her cousin Rían married Húrin’s brother, Huor. Of course, we know by now that things didn’t end well for those two Gondolin-visiting brothers. They both came of age a few years after the Battle of Sudden Flame, but in the Battle of Unnumbered Tears, Huor was slain while Húrin was captured and taken to Angband. When last we left Húrin, he was placed in a stony high-chair and given the supernatural “gift” of seeing Morgoth’s curse fall upon his family. Morgoth is bent on making him suffer.

But before all that, Húrin and Morwen had three kids: one on the way, one a little girl, and the eldest is Túrin.

Túrin

Young Túrin lives in peace and joy only for a short time before he’s hit with his first dose of sorrow. While he’s a quiet kid, his little sister is Lalaith (Sindarin for “laughter”), and she is a creature of happiness. But when she’s only three years old a plague sweeps through the region out of Angband (and this before the Battle of Unnumbered Tears). While the Elves of Hithlum are immune to all sickness (because of course they are), mortal Men are not. Little Lalaith is claimed.

As it’s presented in the original Tale of the Children of Húrin, Lalaith’s death sets the proper tone for the rest of the story. Many young people in Hithlum are afflicted by the Angband-borne pestilence, including Túrin himself, but he eventually beats it. Then he asks to see his baby sister (whose given name is Urwen, with Lalaith being her nickname).

And when Morwen came to him, Túrin said to her: ‘I am no longer sick, and I wish to see Urwen; but why must I not say Lalaith any more?’

‘Because Urwen is dead, and laughter is stilled in this house,’ she answered. ‘But you live, son of Morwen; and so does the Enemy who has done this to us.’

My takeaways from this: laughter is rare in their family, and Morgoth is blamed for it. Both right on the money for all that follows, and yet we’ll see that some of this family’s grief comes from their own choices. In any case, Morwen eventually becomes pregnant with Túrin’s next sibling, and that’s when Húrin and the men of the House of Hador go marching off to war, following the lead of the Noldor. And none of those men ever make it back home—nor does the news of their demise.

Easterlings come instead. These Men who allied with Morgoth during the war now occupy Hithlum and the land of Dor-lómin and live by bullying the women, the children, and the old of their defeated enemies. But the Easterlings are still embittered by their crappy-ass arrangement with Angband. The Dark Lord altered the deal and forced them to come and live in this cold northern realm, instead of in the bountiful lands to the south. Who’d have thought making a deal with Morgoth would turn out poorly for them? (Well, they’d best pray he doesn’t alter it any further.)

Túrin is eight years old now. For a little while, Morwen and her son are left alone by their oppressors—almost too alone, for she is poor. The Easterlings are wary of her: she is dark-haired, beautiful, and noble of bearing. They take her for some sort of Elf-loving witch among Men and so she lives apart like some shunned medicine woman, her only valuables being Elf-gifted heirlooms—valuable indeed, but not so much with Easterlings running the show.

Mostly, she fears that it’s only a matter of time before the Easterling occupiers overcome their superstition and take her son away, and lock him up or enslave him. Imagine that: having your kid taken from you. It’s legitimately one of the worst fears a parent has, and absolutely the sort of thing only villains would do.

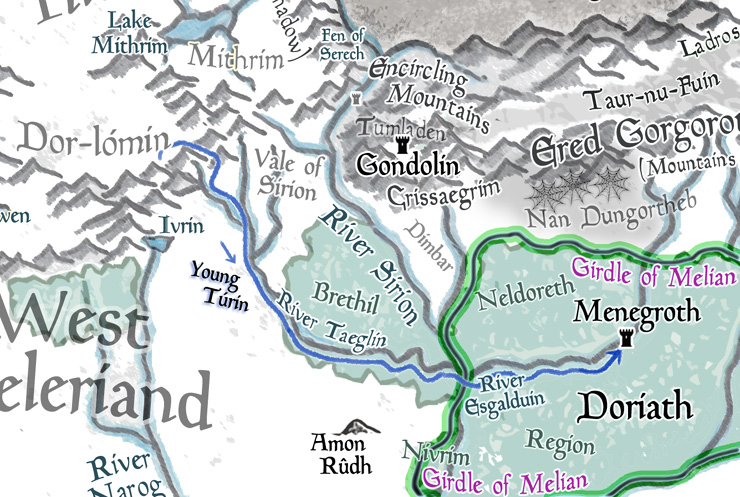

So Morwen makes the terrible choice of sending her son away before he is taken. With the help of two elderly servants, he is sent in secret out over the Mountains of Shadow, across the Vale of Sirion, and towards Doriath, bearing messages to plead with the Elf-king Thingol to take him in. Why Thingol? Because, Morwen reasons, she is of the kindred of Beren, and doesn’t Thingol now regard his son-in-law favorably? He’d even regarded Húrin well, too.

Note that Húrin also spent time as a young man being fostered by a lord of the Eldar (King Turgon in Gondolin). It’s a pattern. One day young Aragorn, whose father is also removed from the equation, will be sent to Rivendell to be raised by a wise Elf-lord.

And just after she sends her boy away, Morwen gives birth to a daughter: Nienor, a second little sister! But this one Túrin hasn’t met. File that fact away as somewhat important. Now this girl’s name means Mourning, which, while lovely-sounding (NEE-eh-noor), isn’t exactly a great omen. But that’s the headspace Morwen is in right now. Her second child died, her husband is still MIA, and she’s just sent her son away with no guarantee of seeing him again.

As a point of reference, let’s look to her cousin, Rían. We as readers know that her husband, Huor, was slain by an Orc arrow right before Húrin did the whole Orc-arm-hewing-before-getting-captured thing in the last chapter. Rían, pregnant with their only child, received no word of her husband’s fate whatsoever—only Easterling invaders. Instead of remaining in her home like Morwen, she went into hiding with the remnants of the Sindarin of Hithlum, which is not a bad idea in itself. But after giving birth to her son, she left him to be raised by the Elves-in-hiding and went out alone onto the plain of Anfauglith, found that great mound of the dead piled up, and just laid down upon it. She called it quits. Game over. No explanations, no mourning, just a matter-of-fact end. At least Morwen is trying to weather the grief.

In any case, Túrin and his aged escorts come to Doriath, where border-security chief Beleg Strongbow, a veteran of both the Hunting for the Wolf (Chapter 19) and the Battle of Unnumbered Tears (Chapter 20), finds them. In the full tale, the young boy and his escorts are actually first “enmeshed in the mazes” of the Girdle of Melian and come near to starving! But upon discovering them, Beleg secures permission for their admittance. As was hoped, King Thingol does take the boy in, and is in fact happy to raise him as his own. Gosh! Talk about doing a one-eighty since his “into Doriath shall no Man come” days, eh? He even sends Elf messengers sneaking back to Morwen in Dor-lómin, trying to convince her to come, too. I almost don’t recognize this guy!

But Morwen won’t come. She won’t leave the house she shared with Húrin. It’s somewhat understandable but deeply regrettable—and also one of the first bitter choices made in this chapter. How things might have been different! And this is another dollop of sadness dropped onto young Túrin. His mom won’t come to be with him, nor bring his new little sister, because…because why? Grief and pride seem to be holding her back.

One thing Morwen does do is send back with Thingol’s messengers the most important heirloom of the House of Hador: the Dragon-helm of Dor-lómin. This Dwarf-made, rune-etched, grey-steeled, and gold-rimmed helm is crested with the image of Glaurung himself, long before the daddy fire-drake had grown to full might. It was wrought to commemorate Fingon’s first encounter with the dragon and his driving the beast back. The original Tale of the Children of Húrin gives us a bit more:

A power was in it that guarded any who wore it from wound or death, for the sword that hewed it was broken, and the dart that smote it sprang aside. It was wrought by Telchar, the smith of Nogrod, whose works were renowned. It had a visor (after the manner of those that the Dwarves used in their forges for the shielding of their eyes), and the face of one that wore it struck fear into the hearts of all beholders, but was itself guarded from dart and fire.

This mighty—and let’s just admit it, magical—Dragon-helm of Fire Resistance, Dreadful Intimidation, and Protection +3 came to the House of Hador, but its most recent heirs failed to make proper use of it. Húrin’s dad, Galdor, wore it plenty but not in his final battle, wherein an Orc arrow to the eye had been his send-off to the Waystation of Mandos (next stop: beyond the Circles of the World!).

Húrin himself actually didn’t want to wear the helm. That’s so Húrin. Not only did he shun such a heavy piece of armor—this being the guy who threw down his shield so he could remove more Orc arms with his axe—but he gave this as an explanation to someone: “I would rather look on my foes with my true face.” That’s just a quote from the Tale of the Children of Húrin, but this reasoning is also the perfect metaphor for him. Which in turn stands in stark contrast to his son’s choices. We’ll soon see how.

In any case, most of the covers for The Children of Húrin include the helm as a symbol for this story.

Speaking of Húrin, it’s worth remembering the end of the last chapter: Due to Húrin’s insolence in the face of Morgoth—who is hellbent on finding Gondolin—the Dark Lord has placed a curse on his family. Morgoth hopes this will break his prisoner, loosen his lips, and yield the location to that Hidden City of Turgon’s. And so, way up on his incommodious Thangorodrim chair of stone, Húrin has a front-row seat to his family’s doom. He’s being made to watch through Morgoth’s eyes—or at least, as much of it as Morgoth can perceive. He is powerful but far from omniscient; he relies on spies and messengers himself, and it may be that he has some means to “pierce all shadows of cloud, and earth, and flesh” as his lieutenant Sauron will do in The Lord of the Rings. Granted, Morgoth’s gaze (and likely his curse) cannot pierce the Girdle of Melian, so while Túrin is still in Doriath, his fate is his own to make. Maybe he’ll just stay there and everything will be all right?

Nine years go by as the boy grows into near-manhood, becoming strong (like Dad), tall (not at all like Dad), and apparently a real looker (definitely more like Mom). Every now and then Thingol sends messengers stealthily over into Easterling-occupied Hithlum to check in on Morwen and little Nienor. But then one day the messengers don’t return, so Thingol doesn’t send any more. Grey-elves don’t grow on trees, you know. Crestfallen, seventeen-year-old Túrin now really fears for his mom and sister. And his way of coping will be in battle. He teams up with Beleg Strongbow, his good friend and mentor. Beleg, I’m convinced, is the Mr. Miyagi to Túrin’s Daniel-san, a much older (and unfathomably wiser) warrior who takes the young man’s training upon himself.

With Thingol’s permission, Túrin takes up a suit of Elven chainmail and a sword, then at last dons the freakin’ Dragon-helm of Dor-lómin. He joins Beleg on the northern marches of Doriath, where his valor and grimness is put to use, slaying Orcs and any monsters of Morgoth’s that come into the region. There’s no mistaking him beside Beleg or any other Grey-elf, not with that fearsome Dwarven helm he’s got! Túrin is still basically a kid, as any adult thinks of someone his age. But as with any world where Orcs regularly raid and plunder, kids grow up fast. Especially mortals. Especially this mortal. And Túrin is his father’s son, after all. There is a lot of blood out there, just flowing freely inside Orcs and other monsters. So Túrin is out there trying to get it all on the outside.

But after three years of this, a disheveled Túrin returns to Menegroth. Beleg is still out in the field, but Túrin stops in for a breather, only to find a jealous schmuck of an Elf named Saeros starting some shit with him. Apparently Saeros (SIGH-ross), who is one of Thingol’s counselors, resents the fact that this sweaty young mortal enjoys the high regard of the king. In a moment of anger, the Elf jests that if the guys from Hithlum are so unkempt and wild (like this here Túrin), what about the gals? Do they just run around naked in the woods, “like deer clad only in their hair”?

Now here’s the thing about Túrin. As we’ll learn, he prefers open conflict, not passive aggression. Real combatants should use swords, not stealthy arrows. If you’ve got a problem with him, tell him to his face. So if Saeros had objected to the “honour” Túrin receives from Thingol, he should just say so. I honestly think Túrin would then address that, probably with strong words but nothing more. As it is, Saeros has made a jest at the expense of the women of Hithlum. And given Túrin’s grief at not having seen his mom in years and never having met his second baby sister, this is the Elf equivalent of Saeros telling a nasty “Yo Momma” joke. So the son of Húrin responds as he tends to: rashly. He picks up a tankard from the table they’re sitting at and straight-up chucks it into Saeros’s smug face. It busts him up bad.

In retaliation, Saeros foolishly tries to ambush Túrin the very next morning as he heads back into the woods. Túrin gets the better of him but doesn’t leave well enough alone. Another heroic Man of the First Age, like Beren or perhaps even Húrin, might have dropped a hogtied Saeros off in Thingol’s court and left it at that. But Túrin has an over-inflated sense of justice. So he forces Saeros to strip down like a deer and run buck naked through the woods…even as Túrin pursues him like a vengeful hunter. He only wants to humiliate the Elf, but doesn’t consider other consequences. Saeros in his fright falls into a chasm, and the rocks of the stream separate his broken body from his spirit, which undoubtedly is now speeding over to the Halls of Mandos.

There happen to be witnesses to the Elf’s end, and one of them is Mablung the Heavy-handed! He’s not heavy-handed about this, though; doesn’t try to haul Túrin off to the Menegroth county jail. Rather, he entreats Túrin to come and face Thingol’s judgement on the matter. But instead, Túrin gets the hell out of Doriath—note, without the Dragon-helm—“deeming himself now an outlaw and fearing to be held captive.” Túrin isn’t murderous (yet!), and he didn’t mean for things to play out this way. If he would just take a moment and think about it, he’d realize that Thingol, who’d raised him like a surrogate father, would surely give him the benefit of the doubt. But alas, Túrin’s shoot-and-ask-questions-later impulses are just getting started. Step one is to run from his problems.

Eventually Beleg Strongbow returns to Menegroth and learns about the Saeros incident. Thingol is upset, of course, but he didn’t want his “fosterson” to just skip town like this. He’s grown to love the boy, and so has Beleg. Thingol tells his chief of security that Túrin would be welcomed back, so Beleg swears to go and find the kid.

The wayward son of Húrin has chosen to play the victim. Not an endearing choice. If he’s a bad guy now, he seems to be reasoning, why not go be among other bad guys? So in woods to the west of the River Sirion, well outside of the Girdle of Melian, he falls in with a rough crowd. They’re a band of woodland-dwelling outlaws, Men who are “houseless and desperate,” all of them most likely the unfortunate products of Morgoth-based hardships. War has displaced them, has probably taken their families, and left them only with empty bellies, weapons, and a lot of aggression. So now Túrin becomes what he assumes others must think of him as: an outlaw, a bandit, one who takes what he wants by force and does not discriminate with victims: Orcs, Elves, Men, all fair game.

Say, maybe some rebranding would help him run from his guilt? Nothing like a new name to set aside your past. So he calls himself…

Neithan the Wronged

As Neithan (pronounced NAY-thun, just like you’d think), he becomes the captain of the outlaws. A year of this harsh life goes by. They operate in the wooded regions south of the River Taeglin, and their new captain does a pretty good job at not being Túrin. He’s left that life behind. Therefore no news of the son of Húrin can be found.

Which is why it takes that long for Beleg, master hunter that he is, that whole year to track him down. When he comes upon the band of outlaws one evening while “Neithan” is away, Beleg is seized, tied up, and generally treated poorly by the Men. They’ve bullied Elves and Men before—and that’s probably putting it mildly—but this one they think might be a spy. They’re ready to kill him, too. But then their captain returns, sees that it’s his old friend and mentor, and it’s like a bucket of ice water on Túrin’s conscience. Beleg represents everything good from his time in Doriath, especially the honor. Elves—the good ones, anyway—ennoble the Men they spend time with. This is a recurring theme throughout the legendarium.

With Beleg “Jiminy Cricket” Strongbow standing before him again, Túrin is forced to consider the life he’s been leading for a year. The “evil and lawless deeds” of his band of Men now weighs on him. Beleg’s presence grounds him, and he swears off banditry. Except against the creatures of Angband. It’s still open season on Orcs!

Beleg tries to convince him to return to Doriath; he’s got Thingol’s pardon for the whole naked-Elf-in-a-chasm thing. And they could sure use Túrin’s sword arm up the northern marches! The Orcs are getting bolder and closer to Doriath’s borders. But Túrin won’t go; pride alone dictates that he turn down Thingols’ invitation to return, but he does try to convince Beleg to stay with him. Which Beleg can’t do. He’s a marchwarden of Doriath and his duty lies in defending his home against the Dark Enemy of the World. The forces of Angband may not be able to get through the Girdle of Melian yet, but that doesn’t mean they can just let all the lands around them fall. The region of Dimbar, for example, is in serious trouble.

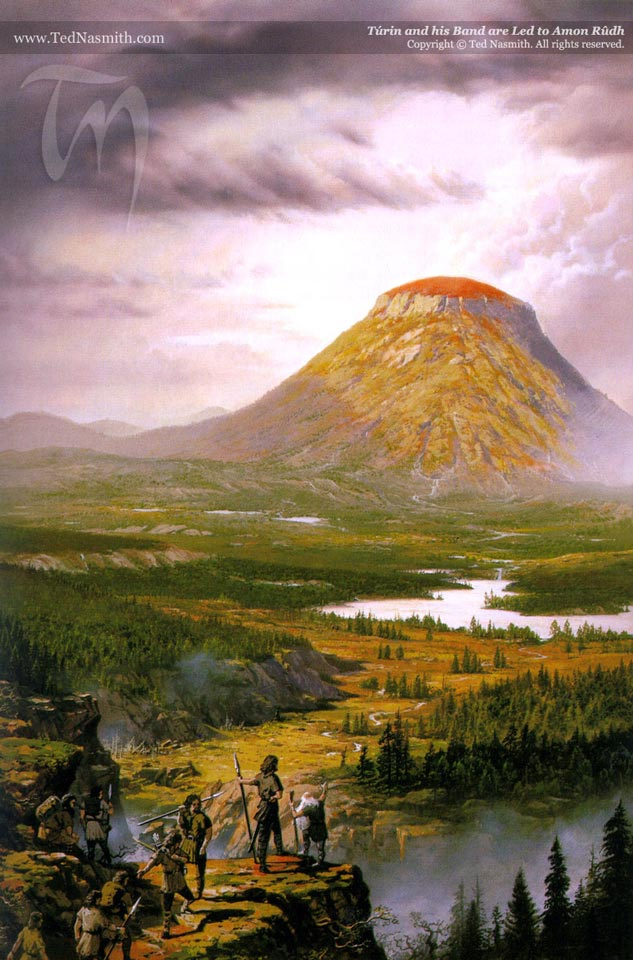

‘Is it farewell, then, son of Húrin?’ said Beleg. Then Túrin looked out westward, and he saw far off the great height of Amon Rûdh; and unwitting of what lay before him he answered: ‘You have said seek me in Dimbar. But I say, seek for me on Amon Rûdh! Else, this is our last farewell.’ Then they parted, in friendship, yet in sadness.

Túrin just picked the distant red-capped hill of Amon Rûdh (AH-mun rooth) because it caught his eye and happened to be closer to him than the northern regions Beleg was returning to. A selfish and arbitrary place to reunite, perhaps, but also a moment of unwitting foresight on his part.

Back in Doriath, Beleg goes to his king and gives him the skinny on Túrin. Thingol is flustered. It’s like he knows that the son of Húrin is important, is destined for greatness, and shouldn’t just be disregarded. Moreover he cares about Túrin. Which can seem odd to some readers, frankly. We see Túrin make a lot of rash and prideful decisions that get people hurt, and yet the people in his orbit, especially all these immortal Elves, seem really drawn to him and treat him with respect not just beyond his years but beyond his race. This might just be a drawback to the summary nature of The Silmarillion. If you read The Children of Húrin, and get the full story of each segment of this tale, you can see there is often more kindness, or at least better intentions, in Túrin’s heart. It might also be that a lot of hope rides on Túrin. He’s among the last of the Edain; the blood of all three houses of Elf-friends flows in his veins.

In any case, Beleg tells his king that if he grants him leave—i.e. lets him retire, at least for now, from being chief marchwarden—then he’ll take it upon himself to guard and guide the young man. There is much good in Túrin; he doesn’t want to see it squandered as an outlaw. Thingol gives Beleg his blessing in this, and offers for him to take whatever he wishes from his royal vault to aid him, so Beleg asks “for a sword of worth.”

Fatefully, Beleg chooses Anglachel, a near-sentient, black-bladed sword that was made by everybody’s favorite Dark Elf smith, Eöl, long ago. Forged from meteoric iron, it can cut through iron of the earth. I can’t help but wonder if the meteorite used came from the spheres of Arda or from Eä beyond it. It raises questions about the very cosmology of this universe…which, frankly, The Silmarillion doesn’t address (but various History of Middle-earth books do tackle, if not comprehensively). In the very least, the falling of this “blazing star” and its manipulation by Eöl, a Child of Ilúvatar, must have at least yielded some lively conversations between two of the Valar: Aulë, whose lordship is “over all the substances of which Arda is made,” and Varda, “who knows all the regions of Eä.”

But I digress. Queen Melian sees which sword Beleg has chosen and warns him of its malice, of “the dark heart of the smith [that] still dwells in it.” (Presumably Thingol rolls his eyes and is all, “My wife and her old wives’ tales, amiright?”) But it doesn’t change the marchwarden’s mind. Beleg may put the “bow” in “Strongbow,” but with Orcs getting thicker in Beleriand, he wants something for close-quarter fighting, and a sword that cleaves through iron will nicely cut through Orc-bones.

Melian one-ups her husband in a way that can literally only be done by an Elf-queen in Arda (or a Maia-in-Elf’s-clothing). She gives Beleg—and by extension, Túrin—the gift of sustenance, a gift like no other. See, you can lend anyone a sword, but what good’s a sword in the wild if hunger is your most persistent foe?

And she gave him store of lembas, the waybread of the Elves, wrapped in leaves of silver, and the threads that bound it were sealed at the knots with the seal of the Queen, a wafer of white wax shaped as a single flower of Telperion; for according to the customs of the Eldalië the keeping and giving of lembas belonged to the Queen alone. In nothing did Melian show greater favour to Túrin than in this gift; for the Eldar had never before allowed Men to use this waybread, and seldom did so again.

I’m thinking that somewhere nearby, Galadriel may be watching this, and thinking she could one day do the same, but maybe add Dwarves to the list of rare recipients of lembas…

So with his royal gifts in hand, Beleg returns first to the northern marches to break in his “new” sword and spill some Orc blood. He and the other Elf-wardens have some success in Dimbar, a region just northwest of Doriath, until winter, at which point he departs again to seek Túrin.

Now we jump back over to the Túrin, a.k.a. Neithan the Wronged, and find that he’s moved on westward with his crew, searching for a more stationary place. For a lair. And one day they stumble upon three diminutive and strange Dwarves right there in the wild—which is a curious place for them to be. Don’t all the Dwarves live in the Blue Mountains or beyond? They only come into Beleriand to work. So who are these hermit-looking fellows? Well, there’s no talk. The Dwarves immediately run, but Túrin and his men are bowstring-happy. The seemingly oldest and least spry of them gets grabbed, while shots are fired at the other two who get away.

Their captive is named Mîm, and he pleads for his life. Mîm (yup, pronounced “meme”) is a peculiar character who incites both anger and sadness at times; a little old man who plays both sides as it suits him, and yet he’s somehow pitiable. In some moments, it’s like the only thing he’s missing is a Precious to pine after. He’s ancient yet scrappy. Mîm seeks mercy: If they’ll spare him, he’ll lead them to his hideout. Túrin, who does pity him, agrees. So where does the old Dwarf’s live?

Then Mîm answered: ‘High above the lands lies the house of Mîm, upon the great hill; Amon Rûdh is that hill called now, since the Elves changed all the names.’

Hah, he totally nailed Elves there. They name everything in sight. Incidentally, Amon Rûdh is Sindarin for “Bald Hill.” The color of its otherwise bare top comes from a plant that grows there, whose flowers are blood red. Yeah, not foreshadowing at all…

So Mîm takes them there, the very same odd mini-mountain jutting up from the land all by itself that Túrin once mentioned to Beleg. But this odd little Dwarf now slaps a new name on the place, calling it Bar-en-Danwedh, the House of Ransom, since bringing these Men there was the price of his life. Inside, through a secret passage, they find the other two Dwarves who had escaped them. They’re both Mîm’s sons, and one has just perished from one of the outlaws’ arrows. Mîm wails and grieves, but Túrin’s surprisingly remorseful, even honorable, treatment of the matter “cools” the Dwarf’s heart. Their arrangement is established: Túrin and his men can stay here, and they have a truce with these Dwarves.

So finally the outlaws are homeless no more. Amon Rûdh is their base of operations, tall enough to provide an excellent vantage on the surrounding regions yet defensible with its high ground, Dwarf-hewn caves, and secret tunnels. Not to mention probably a ton of places to squirrel away their loot. Perfect for these land pirates.

During this time, Túrin learns more about Mîm and his kind: they are the last of the Petty-Dwarves, a disparate people who had been sundered from the rest of Dwarf-kind long ago, way back before the Dwarves of the Blue Mountains made contact with the Elves of Beleriand, before even the Sun and Moon! They’d been banished by the other Dwarves, and it seems likely that even Mîm has no idea what transpired in those ancient days that cast them out. But when they came wandering over the mountains, the Elves that first met them—most likely the Nandor Green-elves—actually hunted them. They shot them with arrows, thinking them some variety of beast. This was also long before Men ever showed up, long before the Noldor returned to Beleriand, and the Elves then had no conception of other sentient beings (except, maybe, Ents?). At some point the Elves left them alone, most likely realizing they were a legitimate race of their own.

Even so, everything about the Petty-Dwarves is sad. They’re not as skilled as their distant kin, they’re smaller, they’re not as strong and able. It may be that their ancestors did something horrible, but who’s to say? It’s all clouded in time and mystery and waning memories. Though they’re not up to par with the Dwarves of Nogrod and Belegost, they were the first ones to start digging and hollowing the earth where the caves of Nargothrond are—that’s where they first hid away from the Elves. But when the Noldor came many years later, Petty-Dwarves withdrew even from there. That’s when Finrod came in and built upon what the Petty-Dwarves had started. Which is why, back in Chapter 13, we got this one little set-up line:

But Finrod Felagund was not the first to dwell in the caves beside the River Narog.

You know, I’m going on the record in saying I think that if Mîm and the Petty-Dwarves hadn’t withdrawn from Nargothrond when the Elves of the house of Finarfin showed up, had in fact chosen to stay and demand recognition for discovery and expansion of those caves, Finrod—being the nicest Elf on Arda—would totally have been on board with their staying. Hell, he’d have probably given them a special wing and place of honor. ♪ He always wanted to have a neighbor…just…like…them. ♫

Oh, Finrod. Beleriand didn’t really deserve you.

Well, he’s gone, and the Petty-Dwarves pretty much dislike everyone except themselves. They hate and fear Orcs, of course, but see, they loathe Elves just as much. Especially the Noldor. Which is really saying something. Men they seem to be lukewarm on. But the Petty-Dwarves have dwindled and just about died out, and now there is literally just one family left, and one’s been killed. So now they’re down to just two—Mîm and one son. Well, at least he has an understanding with Túrin and his gang. They can co-exist. It’s not like there are any Elves around to bother Mîm! So that’s good.

Oh, except…

Midwinter is soon upon them, and it’s getting colder than ever. With Morgoth’s grip on northern Beleriand getting stronger, so too are extremes of nature that he himself inspired in the Music of the Ainur. Túrin’s men are getting hungry, and some are getting sick. And that’s when Beleg shows up again like a jolly old gift-bearing Elf on a cold Christmas morning. He brings supplies, lembas from Melian, and the legendary Dragon-helm of Dor-lómin. Beleg, who was once poorly treated by these men, is now their savior. They’re nursed back to health with the Elves’ vitamin-rich waybread, and Túrin is much happier with his old friend beside him. Frankly, Túrin is just a better person when Beleg is around. But still, the son of Húrin cannot be persuaded to return to the north, where they could really use him. Where his fighting prowess would not be squandered. And yet…

Beleg yielding to his love against his wisdom remained with him, and did not depart, and in that time he laboured much for the good of Túrin’s company.

Love against wisdom indeed. Beleg is loyal almost to a fault, still feeling like this young man has a high destiny. He knows Túrin’s meant for better than this, yet if he can’t get his protégé to leave the bad crowd he’s running with, then Beleg will stay among them and try to lift them all up.

But you know who doesn’t care one bit for Beleg Strongbow hanging out here in Amon Rûdh? Not one tiny bit? Mîm, of course. He stews in his hatred and doesn’t even talk with Túrin anymore. Túrin is clueless.

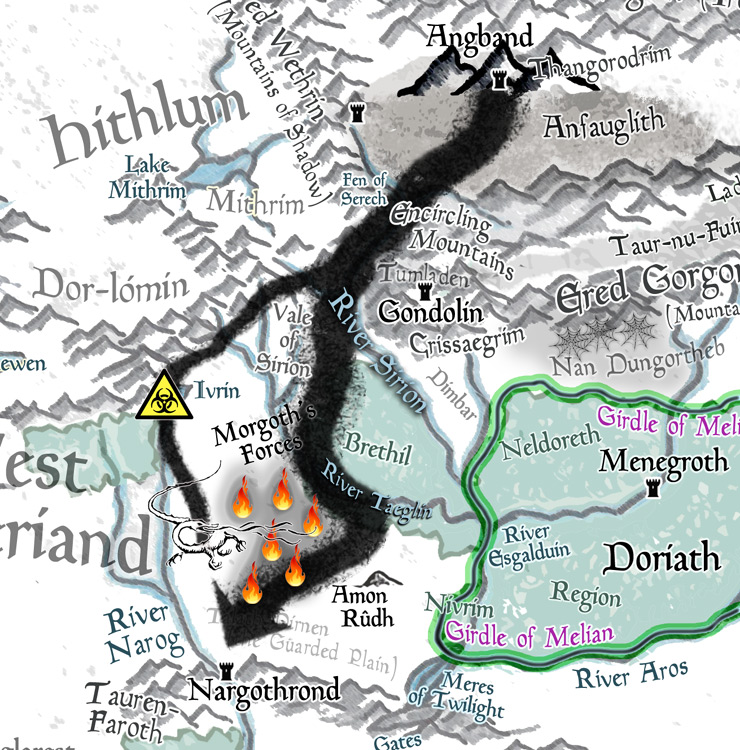

Meanwhile, Morgoth has renewed his search for the Elf-realms that have evaded him. Gondolin is still hidden and Húrin still isn’t talking, so that’s out. He can’t get into Doriath with his armies due to that meddling Maia Melian but he can and does swarm and overtake all the lands around it with his Orcs. Dimbar and the northern marches, the very places where Beleg had wanted to defend with Túrin beside him, are finally seized. Then the Orcs pour southward through the Vale of Sirion, into the woods and plains outside of Brethil. Drawing closer to where Amon Rûdh is situated in that stretch of land between Nargothrond and Doriath. But the Orcs hesitate in their march at this point, because “a terror that is hidden” dwells there with “watchful eyes” looking down from that ominous red-capped hill.

All because Túrin has taken for himself a new name, a third name. No more is he Neithan, or even Túrin. Now all his business cards list him as…

Gorthol, the Dread Helm

Gorthol makes himself a bogeyman to the forces of Morgoth, going out into the wilds around Amon Rûdh wearing the Dragon-helm. Where Beren once went all First Blood against the Orcs in Dorthonion, Túrin as Gorthol is more Rambo III, with fewer guerrilla tactics and more wholesale slaughter of his enemies…with Beleg Strongbow beside him. Remember that Túrin prefers open conflict, but he does so with his imposing Dragon-helm of Sword Snapping and Arrow Deflection.

Word spreads far and wide of the Two Captains who preside over this region, and their crusade against the forces of evil actually heartens others in the region who until now have only cowered. Elves, being Elves, give all the land between the River Taeglin and edge of Doriath a new name: Dor-Cúarthol, the Land of Bow and Helm. Note that while Beleg does still carry Anglachel, that meteoric black blade, he still favors his bow.

Word of the exploits of these Two Captains reaches far: Nargothrond, Doriath, Gondolin…and Angband. Morgoth is especially pleased, for he’s been looking for the son of Húrin. It’s not enough that his Vala-fueled curse has brought misfortune to the family, but if he can actually capture Túrin—who now famously wears the Dragon-helm of the House of Hador—alive, so much the better. Thus the legendary status of this so-called Gorthol allows the Dark Lord to triangulate, if you will, Túrin’s position, and so “ere long Amon Rûdh was ringed with spies.” Morgoth wants Húrin’s boy alive.

Mîm is the one to double-cross him. Orcs “capture” the old Petty-Dwarf while he’s out gathering roots, and he’s quick to give up the location in exchange for his life (again). Now the Orcs can obviously find the hill of Amon Rûdh itself, but they didn’t know the way in. Yet guided by one who knows the secret doors and passages, they now can infiltrate. Mîm demands that “Gorthol” not be slain, though; he’s got a soft spot for the young Man. Which is fine, the Orcs have orders not to kill him. But that Elf, and all the rest of his crew? Have at ’em. See if Mîm cares!

There is a night raid, and a great battle ensues, not outside the red-capped hill but within it. Thus betrayed, Túrin’s men are slain one by one—even those who manage to escape to the outside are cut down. Túrin himself is snatched up in a friggin’ net and dragged away in captivity—precisely the fate he’d been afraid of back in Doriath over the Saeros incident. (Isn’t it ironic? Don’t you think?) Beleg, unfortunately, is also horribly wounded. In the Elf’s moment of vulnerability, Mîm comes upon him and tries to take his revenge against him—against all Elves. But Beleg, even disadvantaged and weaponless, is the faster. He snatches Anglachel out of the old Dwarf’s hands and turns it against him. Mîm runs away screaming, and whether he can hear it or not, Beleg calls out after him:

The vengeance of the house of Hador will find you yet!

Elves! Even when they don’t know stuff, they know stuff. We won’t see Mîm again until the next chapter.

Though it takes time, Beleg patches himself up and searches for Turin’s body in order to bury him. Not finding his young friend, he realizes the Orcs have taken him—alive!—so he sets off in pursuit. It’s a long and arduous journey and he’s way behind them, but Beleg is among the greatest of the Elves of Middle-earth, and the Orcs are easily trackable. He doesn’t get close to catching up until he starts across the dark woodlands of Taur-nu-Fuin (old Dorthonion). But there he chances upon an Elf named Gwindor sleeping beneath a tree.

Yes, that Gwindor, once an Elf-lord of Nargothrond, whose wrathful charge against Morgoth’s forces had kicked off the Battle of Unnumbered Tears. He’d been taken into Angband and enslaved—nearly two decades ago! Now he’s a shell of an Elf, but he was resourceful and bold enough to escape Angband at last…only to be lost and “bewildered in the mazes of Taur-nu-Fuin.”

But Gwindor now joins up with Beleg, for he’d seen the Orcs and wolves pass through with a tall captive, a Man in chains. He advises against trying to rescue Túrin, fearing a return to the mines of Morgoth’s hellish prison. But Beleg is determined, and it’s infectious. The two Elves press on, and finally discover the Orc camp at the north edge of the highland.

The Orcs, now within sight of Angband with their prize dazed and roped to a tree, are all too confident. They’ve got sentries, they’ve got wolves, they’ve got their Man. So they just party and make a ruckus even as a storm draws close—which is perfect for Beleg. He picks off every wolf-sentinel like a sniper, and together the two Elves find Túrin, beaten and senseless but alive. They cut him from the tree and carry him out of the camp as far as they can (he’s no lightweight).

But maybe it’s because the curse of Morgoth is heavy upon Túrin—heck, now they’re literally within sight of the peaks of Thangorodrim—because what follows really, really sucks. Sucks so bad that even the storm wants in on this: Beleg goes to cut away the rest of Túrin’s bonds, because if they can get him on his feet they’ll have a better time avoiding pursuit. But he uses Anglachel—the sword with the “dark heart” of its maker—to do it. And Túrin’s bound in metal chains; he probably has to use the black sword. Well, the blade nicks Túrin in the foot, which wakes him suddenly. Dazed and confused, the cagey young man sees a figure with a blade standing over him backlit by a goddamned lightning storm. The son of Húrin’s violent impulse takes over. He wrestles with Beleg, pries the black sword from him, and runs him through.

Ugh.

This must be a blade-straight-through-the-heart situation, because Beleg’s death is instant. There’re no last words of parting, of sorrow or forgiveness. No customary moment of foresight. Just death.

Túrin, seeing what he’s done, just freezes up. No weeping, no words, just staring. Gwindor has witnessed this—yikes, talk about crazy first impressions! Fortunately, the Orcs interpret the storm as a bad omen: once they discover that their captive is gone, and that the winds of the storm have come from the west, they fear it is Morgoth’s own “great Enemies beyond the Sea” who have intervened, so they run back towards Angband empty-handed. Which, in a tale so full of woe, is a stroke of good fortune (if fortune we’ll call it), since Túrin just sits witless beside the body of his best friend.

In the morning, Gwindor snaps Túrin out of it just enough for them to bury Beleg in a shallow grave, then get the heck out of there. Days go by as Gwindor, recovering the sword Anglachel, takes charge of the situation. He is himself a shadow of what he once was, a despondent Elf for so many reasons—having lost his brother, his home, his mettle, and (for twenty years) his freedom—but it falls on him to lead the now-even-more-useless trancelike Túrin away. They avoid the Orcs who give chase and wander westward away from Taur-nu-Fuin altogether. They don’t talk. Túrin is shell-shocked to the core, and the grief on his face “never faded.” Not through all that follows.

Gwindor leads them to the pools of Ivrin, a great stone basin where cool waters collect from Mountains of Shadow, and the source of the River Narog. Blessed and shaped by Ulmo himself, according to Gwindor. Here they are refreshed from their weariness. And drinking from the mountain waters, Túrin is forced out of his stupor. He drops to the ground and finally weeps for his friend, and is thereby “healed of his madness.” He even composes a song for Beleg, the Song of the Great Bow, and there at Ivrin sings it aloud.

Then at last he talks with his new companion, Gwindor, learning who he is and where he came from. Not only is he a veteran of the last great war, he fought with Fingon and the Elves of Hithlum. Just like Túrin’s dad. It turns out that even as a slave, Gwindor knew a little bit about Húrin’s predicament:

‘I have not seen him,’ said Gwindor. ‘But rumour of him runs through Angband that he still defies Morgoth; and Morgoth has laid a curse upon him and all his kin.’

‘That I do believe,’ said Túrin.

For most of us, a bit of misfortune can lead us to conclude that the universe conspires against us. But when Túrin stubs his toe, loses his wallet, or mistakes his best friend for an Orc and slays him outright, he can rightly attribute at least some of it to an actual cosmic curse. Cosmic in the sense that a former Vala, diminished of his original might but possessing way more power than any Child of Ilúvatar, really has it in for him. But more importantly, this is the first time Túrin is hearing about it. He’s now cognizant of an actual curse. Which we’d like to think means he will tread more carefully from now on.

But that’s so not Túrin.

Gwindor also gives him Anglachel, and Túrin can sense its badassery. Gwindor, with his Elvish sensibilities, adds that the blade “mourns for Beleg,” too. Then he tells Túrin he’s going to return now to Nargothrond. He’s more than welcome to come with.

When they finally reach Nargothrond, they’re treated suspiciously, for they scarcely recognize Gwindor. Although he’s an Elf, to other Elves he seems oddly aged and withered. Then we meet Finduilas (Fin-DOO-ee-las), the princess of Nargothrond and daughter of Orodreth (Finrod and Galadriel’s brother). She was once Gwindor’s girlfriend, and she at least recognizes him. And since Gwindor vouches for Túrin, he’s allowed to stay, too. But he doesn’t allow Gwindor to speak his name. Instead he introduces himself differently. Now he’s…

Agarwaen

Túrin kicks the melodrama into higher gear here, since Agarwaen means the Bloodstained, and he pairs it with “the son of Úmarth, or son of Ill-fate.” He doesn’t want it getting out who he really is. His cover story is he’s just a woodland hunter. Never mind the distinctive dragon-crest helm or this totally unique black sword he’s carrying. He’s just some guy. Some super-duper handsome, hero-looking guy.

But the Elves of Nargothrond—who history, we must admit, has shown to be rather flighty with their loyalties—don’t let this Agarwaen (AH-gar-way-en) be just some guy. He oozes too much charisma without even trying, despite his stern demeanor. Moreover, he’s physically attractive; still young and fit, still the son of the ravishing Morwen, a.k.a. Eledhwen the Elfsheen. He is quite literally tall, dark, and handsome, “his face more beautiful than any other among mortal Men, in the Elder Days.” Hey, he’s like the male Lúthien—Ilúvatar’s gift to Men! You know, minus all the smart thinking, good judgement, and a penchant for not getting all her friends killed.

Since these Elves don’t know that their new Agarwaen friend already has a growing list of names, they decide he needs another. So given his good looks and Elvish mannerisms (owing to his growing up mostly in Doriath), many take to calling him Adanedhel (ah-DAN-eh-thel), which means Elf-Man. So that’s yet another name, and surprisingly one that Túrin himself didn’t come up with. But the renaming doesn’t stop there. The edges of Anglachel had become dull, so the sword gets reforged by “cunning smiths” (still plenty of craft-loving Noldor in Nargothrond!). Then Túrin—err, “Agarwaen”—calls it Gurthang, or Iron of Death. Because of course he does. Why shouldn’t Túrin/Neithan/Gorthol/Agarwaen/Adanedhel’s weapon of choice not also get rebranded?

With his reworked sword and a scary-ass dwarf-mask that he retrieves from the city’s armories, Túrin heads out into Talath Dirnen, the Guarded Plain, that open land between Nargothrond and Doriath, and once again he goes out into battle. Whenever Orcs encroach, he is there to terrify and to slay. There sure are a lot of layers he’s heaped upon himself, to run from the Man he was, and from the family he came from. In fact, he gets another name yet. That’s three from his time in Nargothrond alone!

“Hold my mead…”

Mormegil

Mormegil means Black Sword, and it’s under that figurative banner that Túrin further buries himself. But the Elves love it, and him, and they marvel at his skill. They’re convinced he can’t be defeated, “save by mischance, or an evil arrow from afar.” To which I’d personally be like, please stop listing ways I can die. But mischance? That might just be on the nose. Yet it’s true, Túrin somehow upstages everyone, even here in this city where there are still Calaquendi Elves, who saw the light of the Two Trees in Valinor and once knew Melkor when he walked among them. That’s nothing to sneeze at. Yet the Mormegil is high in the favor of Orodreth, just as Túrin had been with Thingol. Gosh, it sure has been a while since he used his given name.

And then it comes to pass that Finduilas, the Elf-maiden who was once Gwindor’s best girl, falls for Túrin “against her will.” That phrase isn’t necessarily used ominously here. It seems unlikely to me that Morgoth’s curse could induce love—lust, maybe. It may simply be that she didn’t mean for it to happen. But she also can’t deny it. Yet her love is an unrequited one, and Túrin himself is clueless about it. Gwindor, not being as handsome or as strong as he once was, never even tries to win her back. This isn’t an ’80s teen film; there are no boomboxes or Peter Gabriel songs to speak of. Morgoth has taken too much from him. But he does gently try to dissuade her for her own sake. Gwindor’s is a two-pronged argument:

-

- Elf and Man relationships are rare for a reason, and this mortal is no Beren.

- This Man in particular is perilous to be with, for he is Túrin, son of Húrin, and some kind of malevolent curse lies on that family. Only “bitterness and death” will come from loving him.

Soon enough, the Bloodstained son of Ill-Fate finds out what his friend Gwindor has done, from Finduilas herself. Gwindor’s gone and outted him as Túrin, and Túrin’s pissed.

‘In love I hold you for rescue and safe-keeping. But now you have done ill to me, friend, to betray my right name, and call my doom upon me, from which I would lie hid.’

But Gwindor answered: ‘The doom lies in yourself, not in your name.’

Gwindor totally nails it, but also we now have it from Túrin’s own mouth that all his names are about hiding from his fate. And I love that Gwindor points out you can’t just hide from your doom. Names, masks, helms–Túrin can’t run from who he is. It’s precisely what Húrin never did, remember? “I would rather look on my foes with my true face,” his dad once said. When will Túrin look on his foes with his true face?

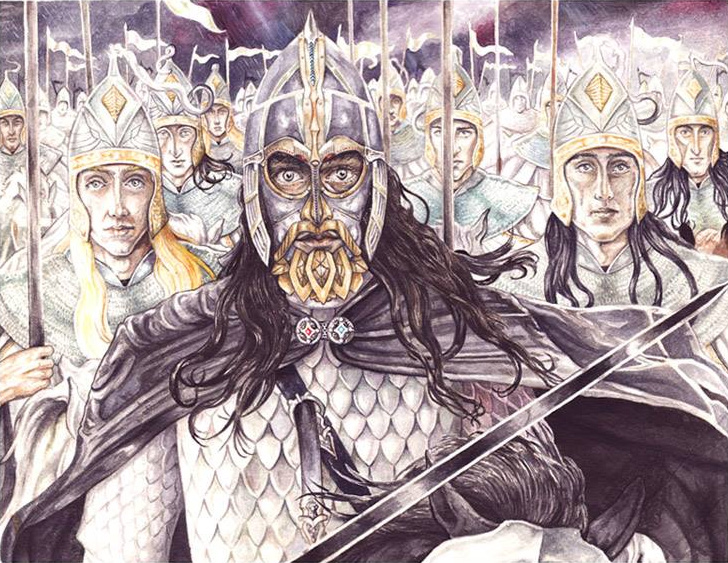

Soon the rest of Nargothrond finds out who he is, but the Elves aren’t fazed by it. If anything, they like Túrin more. He’s a legend come to life. But he doesn’t think much on Gwindor’s wisdom, keeps on hiding from his past. He asks all the Elves to keep his secret, but he does take advantage of their love of him. With the King in his corner, he advises against all the Elf-kingdom’s longstanding surreptitious manner of warfare, “of ambush and stealth and secret arrow,” and now pushes for his own personal style. He’s proven himself in battle, and Orodreth buys into it, reversing their centuries-old strategic positions for Túrin alone. They rework their budget and now put everything into a “great store of weapons.” He’s basically like their commander-in-chief now. Gwindor tries to speak out against this, but no one’s listening to that sorry old sap now.

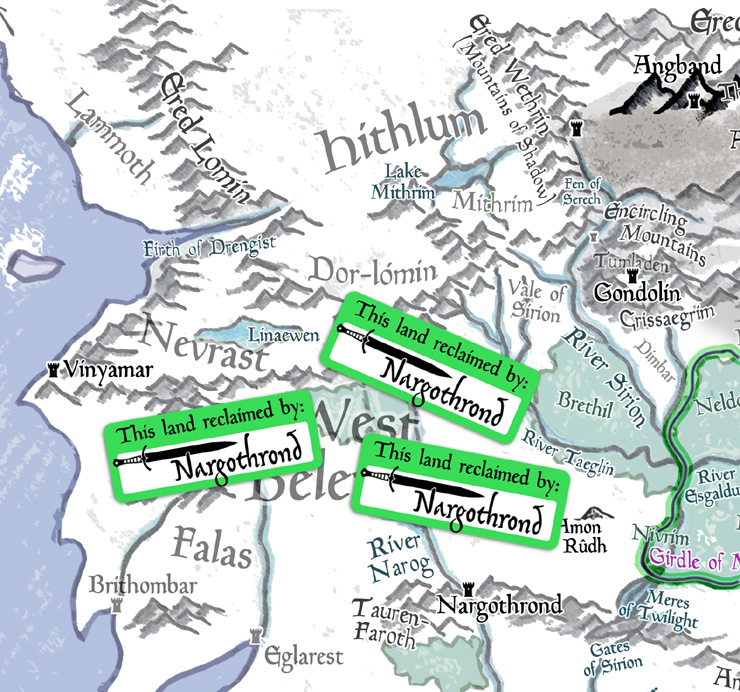

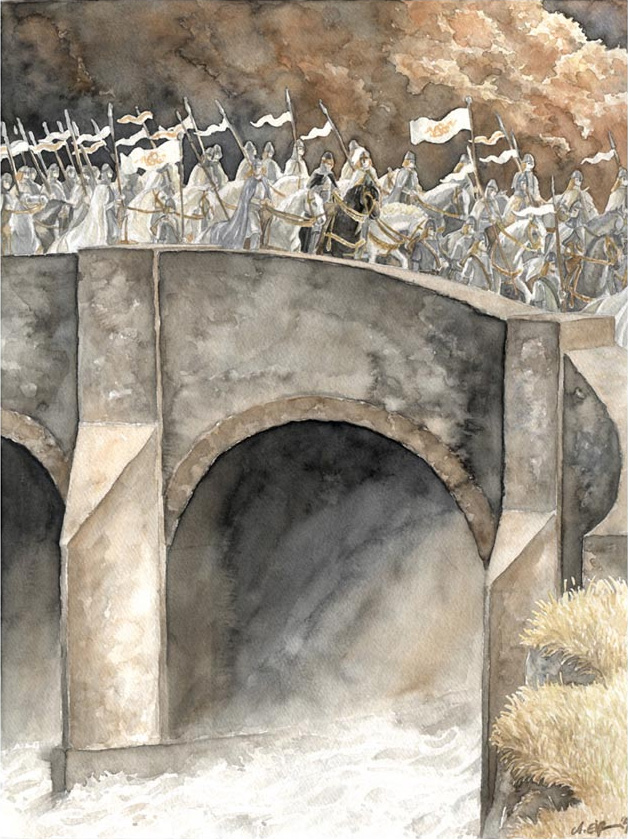

Túrin even convinces the Elves to build a bridge across the River Narog directly from the main gate, where before there was none, “for the swifter passage of their arms.” Prior to this, even though the city of Nargothrond wasn’t as hidden as Gondolin, nor as supernaturally protected as Doriath, it was nigh-inaccessible. Morgoth’s forces would not have been able to lay siege across a river, and the secret passages into the cavern-city were hidden. But now? Well, at least the Elves can issue forth…faster? I guess that was needed? Well, let’s see where Túrin’s going with this. Hold his mead…

So at the Black Sword’s prompting, the forces of Nargothrond go out in greater force than ever before and clear out the land between the River Sirion and the River Narog, and even out west as far as the coast.

Which, of course, really catches Morgoth’s eye. It’s not just the rising of the Black Sword—the Dark Lord might be guessing who that is—but it’s the fact that one of the three “hidden” Elf-kingdoms has dared to reveal itself. To put it another way, Nargothrond has dared to stick its head up in Beleriand’s epic game of Whac-A-Mole, and Morgoth’s mallet has been eagerly waiting for a mole to whac.

There is one little upside to all this, though: due to Nargothrond’s aggression and the temporary relief it has brought to West Beleriand, way up in Dor-lómin, Túrin’s mother finally decides to risk leaving her Easterling-occupied home. Morwen knows nothing about what’s really happening in the south, or that her son has been instrumental in it; she knows only that there is “respite” for these western lands. So with her daughter, Nienor—who has grown up now into a young woman—she finally makes the crossing eastward to Doriath. Thingol receives her as he always wanted, but Morwen herself is dismayed to find her son not in residence. Still, at least they’re safe and, maybe more importantly, in a place where they are not treated like crap.

And then Tolkien gives us rare moment of precise time. It’s effectively the spring of 495, counting up from the years since the rising of the Moon (and the Sun a few days later). Two Noldor show up in Nargothrond, one of whom confusedly bears the same name as Gwindor’s dead brother (but they’re two totally different Elves—maybe “Gelmir” is as common as our “Bob” among Noldor?). These two Elves had formerly served Angrod (Finrod’s brother) up in Dorthonion, but after the Battle of Sudden Flame they ended up living with Círdan the Shipwright way to the south. But now they’re here on official business.

Círdan has sent them as messengers because Ulmo himself, the Lord of Waters, actually visited and spoke with the Shipwright directly. The last time we heard from that watery Vala he was using his powers in the River Sirion to help hide younger Húrin and Huor, whereupon they got snatched up by Eagles and brought to Gondolin. Well, now Ulmo’s influence is almost gone, for Morgoth’s forces have “defiled” the waters of Sirion. The messengers go on:

But a worse thing is yet to come forth. Say therefore to the Lord of Nargothrond: Shut the doors of the fortress and go not abroad. Cast the stones of your pride into the loud river, that the creeping evil may not find the gate.

And by “stones of your pride,” Ulmo means the strong stone bridge that was erected to span the River Narog—the one that allows swift passage to and from the city’s main doors. While Orodreth quails at these dire warnings, Túrin is unmoved. The king, far too soft to make important decisions, looks to their would-be savior, the Bloodstained Black Sword who might as well be the king now. And Túrin’s basically, “Ulmo Whatshisface said what now? Throw down the bridge? Yeah, no. Not doing that.”

And none among the credulous Elves of Nargothrond gainsay him at this point—except Gwindor. But ignoring the wisest person in the room has become a sort of M.O. for the leaders of this age, hasn’t it? And yet that’s not all: on their way here while crossing the Vale of Sirion, the two messengers from Círdan have also spied a huge mustering of Morgoth’s forces. This isn’t just another advance of Orc-bands but a great army. It’s no joke. We’re talking Sudden Flame type shit. Unnumbered Tears numbers. But Túrin’s all whatevs, we can take them. Open warfare, y’all! Somebody hold this guy’s mead already!

Well, Ulmo tried. Círdan tried. Gwindor tried. No one can say they didn’t.

And so the great armies of Morgoth come flowing down in a concentrated force. They sweep partially through the forest of Brethil (where previously they mostly just skirted it), slay the current head of the House of Haleth, and drive those stubborn Men back into the deep woods, and head right into the lands of Nargothrond.

This time Glaurung has come (where previously he only ventured east in the lands of the sons of Fëanor) and because he’s a dragon—the first of dragons—he’s an environmental disaster on legs. I don’t really want to know how, but he defiles the previously clean and blessed Pool of Ivrim, where Túrin had been awakened from his post-Beleg madness. And with his fire he starts to burn everything in the now unsuitably-named Guarded Plain itself.

The Elves of Nargothrond might seem frivolous at times—wishy-washy or fickle, as Alan Sisto of The Prancing Pony Podcast has said—but they are still Noldor. Most of them will recall Valinor, and the Two Trees. They’re Calaquendi, they can put up a fight. And they sure do, marching out at Túrin’s orders to meet the might of Morgoth’s armies. To his credit and misfortune, Orodreth goes, too, with Túrin beside him. Even Gwindor doesn’t sit this one out.

And they fight, and fight hard.

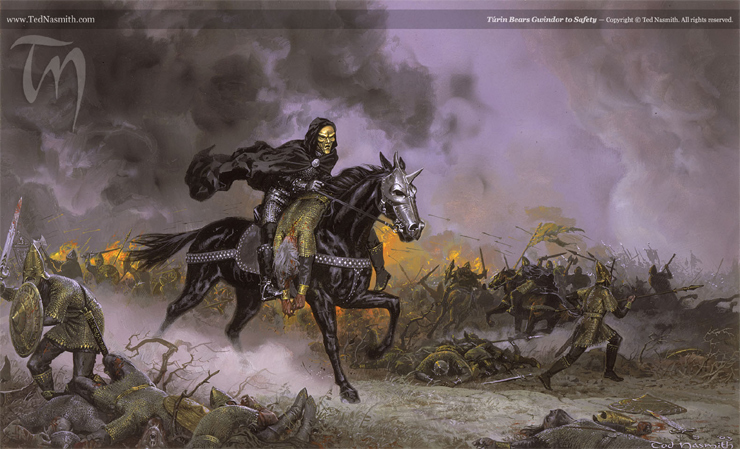

But they lose harder. It’s not even close. The Elves are soundly defeated, especially when Glaurung looses himself upon them. Only Túrin with his fireproof dwarf-mask can withstand him. King Orodreth himself is slain. Gwindor is horribly wounded. In the chaos of the battle, where Orodreth is probably roasted by dragonfire or spitted with Orc-spears all too quickly, Túrin is at least able to rescue Gwindor from instant death. He rides in, scoops his friend up, and rides into some woods nearby.

But Gwindor is done for. Unlike Beleg, he does get some parting words. On the one hand, he loves Túrin and tells him so, but he rues the day they met for it has led to many terrible things. Which is some tough love indeed. If Túrin wasn’t emo before this moment, you can bet he’ll really be stewing in some dark emotions from here on out. He’s just seen all his efforts to defeat Morgoth’s army wither away, and lost another friend.

But there’s still a chance he can can resist this Morgoth-induced curse upon him, according to Gwindor:

Haste thee to Nargothrond, and save Finduilas. And this last I say to thee: she alone stands between thee and thy doom. If thou fail her, it shall not fail to find thee. Farewell!

That’s right, although the army of Nargothrond has been dashed, there are plenty of people back home—the noncombatants. And Finduilas is among them. So all right, he’ll go. Back Túrin hastens, cutting through as many Orcs as he can and even organizing as many of the remaining Elves as he can. He doesn’t just straight-up abandon everyone. Not…yet.

By the time he does reach the great “stones of your pride” bridge, Glaurung and the main host of Orcs have already gone inside and wrecked the joint. Pillaged and ransacked. Those who had risen to defend its halls have either been killed or chased off. The “women and maidens”—at least, those who weren’t burned outright—were rounded up in chains. Finduilas is one of them.

Túrin now goes alone across the bridge. It’s time to do the right thing.

And out comes Glaurung to greet this courageous and foolish Man who approaches with a black blade in his hand. This can only be the famous Mormegil.

Then suddenly he spoke, by the evil spirit that was in him, saying: ‘Hail, son of Húrin. Well met!’

In other words:

’Sup?

In the next installment, we’ll pick right up from here and find out how Túrin outwits the dragon, saves the princess, frees the captives, and drives the forces of darkness from the face of Middle-earth forever. Or, I guess, at least considers it.

Also, he’s still got at least one more name in the works, ready to enter, stage right.

Top image from “Sack of Nargothrond” by Donato Giancola

Jeff LaSala just has the one name + middle name + last name, but it sure would be cool to have carte blanche on renaming ourselves, wouldn’t it? Tolkien geekdom aside, Jeff wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books. He is sometimes on Twitter.