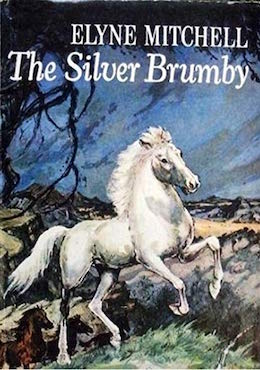

For years my horse friends have been telling me about the Australian classic, Elyne Mitchell’s The Silver Brumby. It’s a must-read, they said. It shaped our youth. You can’t miss it.

Finally one of my writer colleagues took matters into her own hands while clearing out her book collection and sent me her childhood copy—hardcover, with illustrations. It’s a precious gift. Thank you so much, Gillian Polack!

We’re out of summer now in the Northern Hemisphere—but the Southern is just turning into spring. Aptly enough, then, here’s a Down Under version of the Summer Reading Adventure.

The story is fairly standard. Wild horse is born, grows up, deals with horse friends and enemies, and fights constantly to keep from being captured and tamed. He would literally rather die than be domesticated. (Which is rather ironic considering that there are no truly wild horses left in the world. They’re all feral—descendants of domesticated horses.)

What makes it so wonderful, and indeed classic, is the quality of the writing. Mitchell knew horses. And more than that, she knew and loved the high country of Australia in which her novel is set.

Here then is the story of Thowra, the cream-colored stallion with the silver mane and tail. His mother Bel Bel is a wise old mare and a bit of a rebel. She frequently wanders off from the herd, as she does in order to deliver her foal—but she has good reason for acting the way she does. She’s a cream, like her son, and there’s no way she can vanish into the landscape the way other, more conventionally colored horses can. She has to find other ways to keep herself safe from predators, and most especially the apex predator, man.

Her son is born in a wild storm, and she names him after it: Thowra, which is the Aboriginal word for Wind. She nurses him through the storm, teaches him her wisdom, and raises him to be clever and canny and swift.

Thowra is as independent-minded as his mother, but he has friends and lovers as well as implacable enemies. His friend Storm, even as a mature stallion, never challenges him, and they share grazing and guard duties while also keeping their own individual harems of mares. He lures the beautiful mare Golden away from her human owner and sires a filly on her. He battles ultimately to the death with his agemate Arrow, and challenges the great stallion, The Brolga, for the kingship of the mountain pastures.

And always, wherever he goes, he’s hunted for his beautiful pale coat. One man in particular, the man on the black horse, pursues him year after year; later, after Thowra steals Golden from a supposedly secure enclosure, Golden’s owner also takes up the chase. In the end it’s an Aboriginal tracker who comes closest to conquering him, because, as Mitchell says, his people are far older and far more completely a part of the land than any horse, however wild. Horses, like white men, are colonizers, though they’ve made this country their home.

Mitchell evokes the natural world in exquisite and loving detail. She knows and deeply loves horses, and while she subscribes to the anthropocentric view that stallions are the leaders of the wild herds, she still opens with the wise elder mare, and Bel Bel’s presence is continuous and pervasive. We get the romance of the beautiful stallion, but we also get the strength and profound good sense of the mare.

I am not a fan of talking-animal stories, at all, but I loved this one. The animals talk, yes, but it feels more like a translation than the imposition of human language and values on nonverbal animals. When the horses converse, their conversation rings true. They would, in their way, discuss where to find food, how to escape predators, what to do when the pastures are snowed in and the only alternative is to trespass on another herd’s territory.

Even the names make a decent amount of sense, if we see them as translations from body language and sensory impressions into the oldest human language of their country. They’re named after natural phenomena (wind, storm), birds and animals (The Brolga, Yarraman), even weapons that might be used against a horse (Arrow), and of course colors (Golden). They’re all concrete, because horses are not abstract thinkers, and they have meaning aside from the human words.

What also makes it work is the deft use of omniscient narration. We know the author is there, telling the story, and we get enough of a human perspective to understand what the horses are doing and saying and thinking. She’ll sometimes explain what’s going on that the horses couldn’t know, and that’s helpful, too—and skillfully done.

It really is just splendid, and I’m glad I finally had the chance to read it. Especially since I was reading it with SFF Equines in mind—and while the writing is powerfully realistic and solidly based in the real world, it’s also epic fantasy.

Buy the Book

The Ruin of Kings

I mean look at it. We have the prince, the son of the king, born in a storm so powerful it shakes the world. His appearance is distinctive and can’t ever be hidden; it’s both his strength and his greatest weakness. He’s raised by the wise queen who understands the wild magic, and taught all of her secrets. He sees the destruction of his father and the fall of the kingdom, and flees into exile, until at last he’s grown into his own powers and can return to challenge the usurper.

He has a brother in arms, too, with never any jealousy between them. They grow up together and fight together and win their victories side by side. And of course he finds and wins his own queen, his favorite among the harem.

Mitchell is well aware of the epic quality of her story. Here it is, right here:

Thus it was that Bel Bel and Storm alone knew how Thowra vanished from his hunters, and when they heard horses—or cattle—say, ‘He is like wind—he must be purely a child of the wind—he comes from nowhere, he vanishes into nowhere,’ they would smile to themselves. Yet they, too, half-believed that Thowra had become almost magic, even though Bel Bel knew that it was she who had woven a spell over him at birth, and given him his wisdom and his cunning, all that made him seem to have the wind’s mystery.

And here, look:

Here was the most beautiful stallion the great mountains had ever seen, in his full strength, fighting for his mate, and it was as though everything round was hushed and still: no wind blew, and the leaves held themselves in perfect quiet. Even the sound of a little stream was muted, and neither the red lowrie nor the jays flew by. There was nothing but the pounding hooves and tearing breath of the two huge horses.

Fantasy readers (and writers) live for prose like this. For a horse kid of any gender, it’s everything that horse magic can ever be, and it’s as real as the pony in the stable or the horse in the pasture—or the feral herd in the mountains, whether of Australia or the American West. It’s no wonder this book is so beloved.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks by Book View Cafe. She’s even written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. Her most recent novel, Dragons in the Earth, features a herd of magical horses, and her space opera, Forgotten Suns, features both terrestrial horses and an alien horselike species (and space whales!). She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.