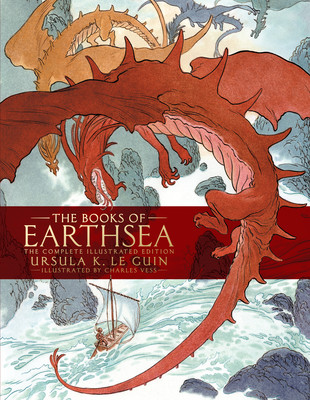

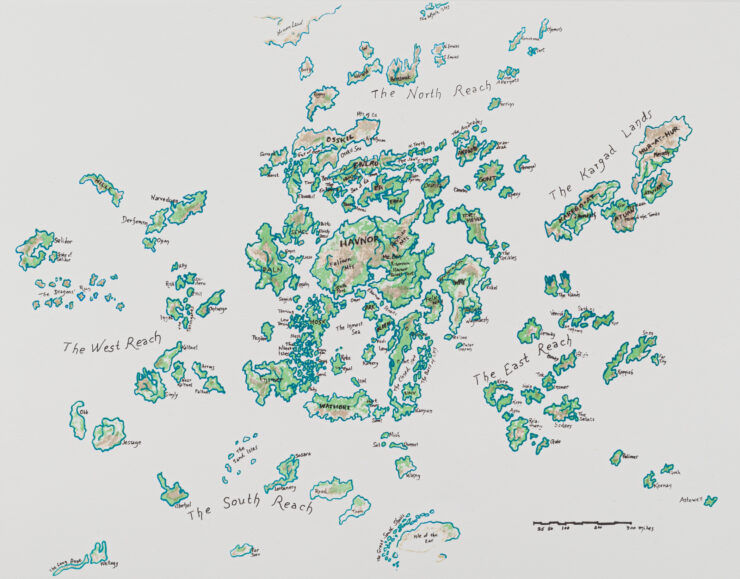

This week, Saga Press releases a gorgeous new omnibus edition of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Books of Earthsea, illustrated by Charles Vess, in celebration of A Wizard of Earthsea‘s 50th anniversary. In honor of that anniversary, this week we’re running a different look at Earthsea each day—starting with the first book in the series.

“A great many white readers in 1967 were not ready to accept a brown-skinned hero,” Ursula Le Guin wrote in 2012 in an afterword to A Wizard of Earthsea, forty-four years after the seminal novel—the first in the Earthsea cycle—was published. “But they weren’t expecting one,” she continued. “I didn’t make an issue of it, and you have to be well into the book before you realize that Ged, like most of the characters, isn’t white.”

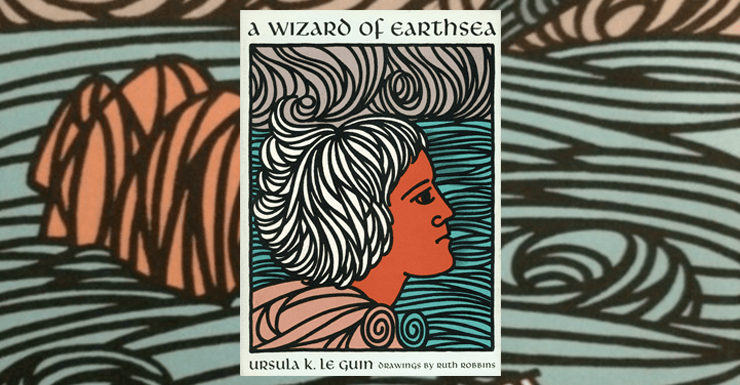

That Ged, the novel’s protagonist, was nonwhite did, however, create consternation for the book’s cover, as Le Guin noted in her afterword. It was one thing to write a brown character; it was another to have the audacity to request one appear on the cover. Perhaps out of the fear that seeing a brown figure would deter readers—African-American sci-fi writers were similarly told, for decades, that there was no market for their work, as black people, their publishers presumed, did not read sci-fi, and white readers might similarly be turned off—Ged was repeatedly depicted as “lily-white” on many of the book’s covers. To Le Guin’s joyous relief, the book’s original cover features an illustration by Ruth Robbins, in which Ged, faintly resembling a figure from either a medieval painting or Art Deco, has a soft “copper-brown” complexion. It was “the book’s one true cover,” she said fondly.

A Wizard of Earthsea was riveting, yet conventional—except in the important way that its main characters quietly subverted one of British and American fantasy’s most notable tropes, in which white, often Europeanesque figures are the presumptive standard. Heroic characters in sci-fi or fantasy who looked like me—brown or black, hair tightly curled—seemed strange, impossible, like the dreams of a forgotten circus tent. While the novel’s female characters left something to be desired—as Le Guin herself acknowledged in the afterword—its embrace of brown and black figures as protagonists was revolutionary for its time, particularly in a decade in which a fiercely divided America found itself embroiled in tense, often bloody debates over civil rights for black Americans.

I came to the Earthsea series late. The first book surprised me in its elegant simplicity. At the time, I had read SFF by some writers of color already, from earlier efforts, like W. E. B. Du Bois’ short story “The Comet,” to works by Octavia Butler, Nalo Hopkinson, Samuel Delany, and others, as well as graphic texts featuring a diverse cast of characters, like Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ series Saga. A Wizard of Earthsea both reminded me of them and was unlike them, all the same, in the way that it told such a standard but gripping narrative for its genre. I breezed through it in bed, on the rattling subway, on a weekend trip with my partner. It felt enriching to enter a world where people whose skin resembled mine were the majority, the norm, the foundation of a world. It felt surprising and courageous, too, when I remembered the date of its publication.

A Wizard of Earthsea tells a classic tale—“conventional enough not to frighten reviewers,” in Le Guin’s words. It begins with Ged as a boy learning that he may have the ability to use magic from a duplicitous witch; Ged’s powers, raw but potent, save his village from an attack by barbarians. Ged ventures to a wizarding school, where he learns the greatest key of magic: that knowing the true name of something gives one control over it. From his early days in the school, however, another boy, Jasper, repeatedly provokes Ged, looking down upon him for his humble bucolic origins. When the two decide to see who possesses the greatest magical ability, Ged naively and arrogantly claims he can raise the dead. He does—but at great cost, as an evil, monstrous shadow is let loose into the world from his casual rending of the boundary between the living and the dead. The shadow attacks Ged; he is only saved from it devouring his soul by the quick appearance of a mage from the school, who scares it off. After the assault, Ged is left near death and with almost all his power gone, and the rest of the book sees him attempting to both regain his powers and finally face down the shadow. The shadow is the result of his inexperience, his hubris, his braggadocio—but it is also the perfect foe for Ged, who eventually learns that he can never fully escape his shadow, for it also represents Ged himself. The past is never dead, as Faulkner tells us; our shadows never quite disappear, even when we think they do.

From the start, Le Guin flips the genre’s standard racial dynamics. “The principal characters [in fantasy] were men,” she said in the afterword, and “the hero was a white man; most dark-skinned people were inferior or evil.” But in her novel, the first antagonists Ged encounters are “a savage people, white-skinned, yellow-haired, and fierce, liking the sight of blood and the smell of burning towns.” In the final third of the book, Ged, shipwrecked by the sinister shadow on a desolate bit of reef, reflects that he “is in the very sea-roads of those white barbaric folk.” The novel does not go as far as to suggest that lightness of skin is bad, a sign of inferiority or inherent iniquity; instead, it simply and naturally, without drawing attention to itself, reverses the racial dynamics so common in American and British fantasy, wherein I’m so accustomed to seeing someone with skin like mine or darker as the casual, callous villains.

Buy the Book

The Books of Earthsea

Fantasy (and, to a lesser degree, sci-fi) is at once far removed from our world and, often, an echo of it all the same—and that echo is not always pleasant. For all the pomp and imaginativeness of its worlds, a great deal of fantasy of A Wizard of Earthsea’s era skewed conservative at its core, able to imagine orcs and dragons but scarcely able to envision relationships that defied the tropes of a heterosexual nuclear family.

While the foundations of a fantastical world are up to the author, it is telling when even the realms we can invent, almost from scratch, so closely resemble the simple foundations of a non-liberal weltanschauung, embodied in the traditionalistic landscapes of a vague medieval Europe so common in certain fantastical tales; there may be war and bloodshed and political upheaval, but little to no political subversion in how gender or sexuality are represented. The males desire and pursue the females; in some cases, fantasy tales simply replicate the white American nuclear family dynamic of the 1950s. When humans or humanlike beings appear, they are often white if good and darker-skinned if bad; men were overwhelmingly heroes, while women were usually relegated to being beauteous damsels in distress or deceitful seductresses, the latter often crass symbols of Orientalism or simply of misogyny.

A Wizard of Earthsea can’t be praised for its depiction of women. To her credit, Le Guin was aware of this failing. She chides fantasy of Earthsea’s era for having women—if women were present at all—who were usually merely “a passive object of desire and rescue (a beautiful blond princes); active women (dark witches),” she continued, “usually caused destruction or tragedy. Anyway, the stories weren’t about the women. They were about men, what men did, and what was important to men.”

Ironically, so is A Wizard of Earthsea. “It’s in this sense,” she acknowledged, “that A Wizard of Earthsea was perfectly conventional. The hero does what a man is supposed to do….[It’s] a world where women are secondary, a man’s world.” Though I’m happy Le Guin could admit this failing, it’s frustrating to read a book that seems so quietly surprising in one way—its natural reversal of racial dynamics in fantasy—and so hackneyed in another—its portrayal of women as little more than beautiful or deceiving objects. The world is heavily male; the narrator refers frequently uses male pronouns as a way of suggesting general or universal truths. Women appear only on the margins, and when anyone distaff does appear, she is merely an object of beauty or a deadly, deceiving lure for Ged.

Just as Le Guin worried about centering nonwhite characters in A Wizard of Earthsea, the idea of female protagonists in fantasy and sci-fi has a long history of controversy. When L. Frank Baum wrote The Wonderful Wizard of Oz—sometimes considered the first genuinely American piece of fantasy—Baum received resistance from readers unnerved by the idea of a little girl as the hero. (Of course, this conception had already appeared in Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland books.) Similarly, as Justine Larbalestier has explored in The Battle of the Sexes, early sci-fi fans—who were predominantly male—engaged in vituperative arguments about whether or not women should appear in sci-fi stories at all.

Isaac Asimov smirked at the idea. “When we want science fiction, we don’t want any swooning dames,” he said in one of his many letters on the subject to a sci-fi magazine, in which he argued with other letter-writers who called for better representation of womanhood in science fiction. After a man named Donald G. Turnbull wrote a letter to Astonishing Science Fiction in 1938 to argue that “[a] woman’s place is not in anything scientific,” Asimov called for “[t]hree rousing cheers on Donald G. Turnbull for his valiant attack on those favoring mush.” “Notice, too, that many top-notch, grade-A, wonderful, marvelous, etc., etc., authors get along swell without any women, at all,” Asimov wrote in 1939 in another letter about sci-fi. For all the swirling beauty of his imagination, Asimov was scarcely able to imagine something more down-to-earth, dull and sublunary: that women could be autonomous beings, in or out of sci-fi.

Ironically, Le Guin herself would be one of the titans in attempting to complicate how we present gender in sci-fi and fantasy, perhaps most of all in her magisterial novel The Left Hand of Darkness. And more recent texts, like N. K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season or Marjorie Liu’s Monstress graphic novels, feature women at their center; Monstress goes so far as to quietly make women the majority of the characters in its world, never drawing attention to this fact but simply presenting primarily women as its heroes, antiheroes, and villains. Mackenzi Lee’s historical SFF, The Gentlemen’s Guide to Vice and Virtue and the more recent The Lady’s Guide to Petticoats and Piracy, center queer men in the former and a variety of women in the latter, the most notable being Felicity Montague, who fights against sexist seventeenth-century assumptions that women should not practice medicine (or science more broadly), and appears to be on the asexual spectrum—a resonant move, given how infrequently asexual characters appear in literature.

In a more foundational sense, fantasy has long had a problem with race that goes beyond its frequent centering of white characters. The genre gives us carte blanche to create the cosmos anew, yet many of the classic texts of the genre simply replicate old racialist ideas, trying to hide them by making them appear different on the outside; at worst, certain texts become a kind of minstrelsy Halloween parade, where minstrels wear the costumes of orcs, gods, and goblins. What is it, if not racialism, when certain groups of sentient beings all share the same traits, not unlike old bigoted theories from European and American colonists about how all black people, supposedly, shared the same deficiencies?

In this cultural moment, we need narratives that subvert the old assumptions of a genre. To be sure, a white American writer incorporating black characters isn’t the same as a black American writer doing so, as the latter has long had to struggle harder for any baseline form of acceptance. That Le Guin was white doubtless made her book slightly more palatable to certain readers (even those prejudiced against her for daring to write as a woman). And Earthsea’s power did not make things much easier for black writers in the same genres like Octavia Butler, Nalo Hopkinson, or N. K. Jemisin; it is telling that Jemisin, at the Brooklyn Book Festival this year, revealed that she had been accused by an unnamed person of being “uppity” when she gave her tremendous Hugo acceptance speech on the occasion of her third successive win.

But for all its flaws, it’s hard not to enjoy A Wizard of Earthsea—and to think of it, fondly, in a world where characters who look like me are finally starting to seem less rare, less marvelous than finding wisteria on the moon, and the simple magic of seeing someone so different as the main character comes to feel almost as incredible as all of Ged’s feats of goodness and gramarye combined.

The Books of Earthsea omnibus is available October 30th from Saga Press.

Gabrielle Bellot is a staff writer for Literary Hub. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New York Times, Tin House, Guernica, Slate, New York Magazine’s The Cut, Electric Literature, HuffPost, and elsewhere. Find her at gabriellebellot.com.

This was a fascinating essay, thank you!

There are a lot of books featuring women as main characters in the 70s and 80s…just…throwing that out there.

But the sexism, yes, that was an immediate turn-off when I was reading Earthsea as a young teen.

I think I’ve mentioned that Le Guin was the daughter of anthropologists. Unfortunately degrees of sexism are cross cultural. Personally I found Earthsea’s version painfully believable.

The second book, Tombs of Atuan, has a female protagonist and a almost all female cast. Ged is the outsider here and his role is very much to support and enable Arha. He doesn’t rescue her. She saves his life and then together they escape from the Old Ones. The final decision to go or stay is all hers.

Ged himself, even in his first appearance is invariably respectful of women and sees them as individuals not a stereotype. His aunt the witch is no better than any other witch but she teaches him to the best of her ability and he remembers her alongside his male mentors. Serret presents herself as a temptress but Ged sees past that to a woman in over her head and tries to save her from her misjudgement. Yarrow fascinates Ged as being different from anybody he ever met. The narration notes that he’s never known any young girl well. Shy at first Yarrow later reveals herself to be the self confident mistress of the household she shares with her brothers.

By ‘The Farthest Shore’ Ged is telling Arren that old women are worth listening to and calls the dyer Akaren a woman of power and art.

It’s also important to note that Le Guin did NOT use much outlining in her writing process, and most (if not all) of the books following A Wizard of Earthsea were not planned to be written until many years after the initial publication. While Ged is “respectful” to women in the most generous sense of the word, this is likely because our expectations have been so subverted by other fantasy media. Not being a weirdo or jerk is the bare minimum. Equity is the bare minimum. Women’s magic is described as wicked or weak, and confined to that. When he first summons the shadow, the young girl (who grows up to be Serret) that he meets is described as “ugly.” This follows a common pattern in not just fantasy literature. Beautiful women and ugly men are described with a lot more than one word — what about ugly women?? His character has been written as a sexist one, and that he formed my idea of “Ged,” which brings up Le Guin’s introduction of dissatisfying discontinuity throughout the series. In the changes after the first book, she is relentlessly undermining the foundation she built to make Ged a compelling character (not feminist, just sloppy).

Furthermore, I strongly believe that silence is an act of violence.

Irregardless of what came after the first book in this series, Le Guin contributed to a space that makes women feel uncomfortable/unsafe, while validating the men who identify women by their physical features alone, think of women as either weak (good) or wicked (strong, but seldom in the way man is strong), and expect a pat on the back for treating women with generally basic human decency.

Note: Le Guin was an immensely talented individual who did important work regarding various social issues, and none of the above is to suggest otherwise :)

I read A Wizard of Earthsea in the 80s, when I was already used to female protagonists. I remember that I liked the dragons and the idea of true names, but was underwhelmed by the story and the characters. I don’t think I noticed anything unusual about their skin colour. But then, I had read books about Indians all my life.

Ged’s arrogance bothered me even more than the lack of female characters. There are too many stories where the young male hero starts out as a braggart and has to overcome his hubris, as if this were a natural part of being male. Thankfully, in her later books Le Guin created many boys and young men who weren’t like that at all.

@3/Roxana: “The second book, Tombs of Atuan, has a female protagonist and a almost all female cast. Ged is the outsider here and his role is very much to support and enable Arha. He doesn’t rescue her.”

I’d say they rescue each other. She comes from a barbarian and superstitious culture, and he enlightens her. Still, it was my favourite book of the original trilogy.

Asimov’s remarks repeated here surprised me, as he did create the redoubtable Dr Susan Calvin. But then as I recall, in the short story Liar, he pokes fun at her for wanting to be both a scientist and a woman. Apparently he could tolerate the one as a regular character but not the other.

Judging from their quoted comments early science fiction writers like Asimov couldn’t imagine a female character that wasn’t a love interest. It seems to be romantic subplots they don’t want.

@3 Thank you. Eloquently well put.

Thanks for the insights! I appreciate that as she became a more confident and skilled writer, Le Guin was willing to challenge a lot of her earlier assumptions. E.g. @3 Princessroxana: I never got around to the 4th book, Tehanu, but my understanding is that it upends the whole patriarchy of Earthsea? I have a copy buried somewhere I should dig up.

@5 & 6: Asimov was a well-known lecher and creep, such that Frederik Pohl called him on it. I do think his writing has aged better than most of his contemporaries, but mostly because he’s more interested in logic puzzles and big ideas than people. It’s easier to gloss over his mid-20th century cultural assumptions than with someone like Heinlein who makes everything a lecture.

@3 princessroxana

The Tombs of Atuan was the first Le Guin I ever read, way back in the day. It worked: I was seeing everything from Tenar’s perspective, so I got to share her curiosity and astonishment when Ged arrived. Like her, I had no idea who he was, and for me the tale worked very well that way. I never considered him the “hero” of that book, only her.

@8 Personally I hated ‘Tehanu’. IMO it made things worse with it’s reverse sexism not to mention major discontinuity with the original trilogy.

@10/Roxana: I liked it because it added a lived-in feeling to Earthsea, because it had middle-aged protagonists, and because one of them was Tenar.

@10. I was still OK with Tehanu (not much better than OK, though), and the Tales of Earthsea I have read (haven’t read them all) are wonderful. But The Other Wind was an unbelievable letdown, and unoriginal to boot –the whole Land of the Dead resolution was lifted straight from Philip Pullman, and clumsily so to boot. I have adored LeGuin since bumping into The Left Hand of Darkness back in the day, but –come on!

@11. Tenar is always an appealing character, to me at least, and aged Tenar is even better. And almost the only thing I enjoyed from The Other Wind was her sort-of-mentoring relationship with the princess.

Seeing Tenar again was the one good thing about ‘Tehanu’. It wasn’t enough.

I have an opinion I would love to share: displaying women as naive, dumb, silly, or whatever in a fictional book isn’t principally a bad thing. Many fantasy books resemble a medieval world, which contain old-fashioned ways of society, i.e. unfair, repressing, far-from-humane models. So if a fanatsy or sf writer decides to model a world in which women are believably inferior, it’s absolutely fine. Likewise a coherent model of a society in which men are hold slaves is fine as well.

It’s only when women (or people of colour, or people of a certain confession, etc.) are displayed as inferior, naive, dumb, silly, just because the author thinks, that they are all like that and that it’s naturally, it has to be seen as migynistic, racist, and so on. In many olden (and new) books I find characters struggling with their society, their social barriers, unable to reach their goals or fufill their dreams – it’s these moments which make me think about these worlds and compare it with my own. That is where I begin to fully appreciate an author, when an unfair world is described and I encounter a charcater, not even a hero, arguieng, struggling, fighting. Even when they never accomplish any of there wishes, even when they die trying.

Please imagine a not so far distant future, a young member of our society has never ever went through racism, never experienced restrictions because she/he was, what she/he is, should they read perfectly modelled worlds? That is the first version of the matrix, it never worked, Mr. Smith told you so! We need bad and foul worlds for our children, to let them remember, experience, what is has to be felt like to live in such an environment. And for my most beloved author Ursula K LeGuin I have to say, that her second novel in the classic earth sea trilogy meets all these above mentioned requirements. That is why I adore her work.

With many greetings from good old europe to a fantastic site ;)

since english is not my native language, please excuse possible semantic imprecisely chosen words

While I cannot defend Asimov’s comments that you cite, I must also in his defense point out that in 1945 he created a female character who was strong, independent, not a sidekick, not a secondary character, and who was the chief scientist for a multinational corporation. Dr. Susan Calvin was way ahead of her time…

I read the Earthsea books when I was in my early teens. They were good enough that I read all 3, once, but never reread them. For some reason LeGuin had that effect on me. I read Left Hand, Dispossessed, and some other work, but never reread them. It wasn’t like, say, William Gibson, who I bounced off of hard.

Asimov also created Bayta and Arkady Darrel in “Foundation and Empire” who were remarkably strong for their day.

And of course H Beam Piper created a number of strong female characters.

Asimov wrote those magazine letters when he was a teenage fanboy who didn’t know any girls. He does say in his memoirs he now found them embarrassing.

That is not to excuse his treatment of women at cons and elsewhere when he became a Big Name Author.

To start what may be a very long and contentious discussion: why does everyone dump on “Tehanu”? I didn’t think it was so _bad_ …

All I know is I couldn’t finish Tehanu. The discontinuity was a problem but mainly it was the sheer ugliness of the cruelty and abuse.

@15, personally I love stories of people negotiating problematic cultures and teasing out agency and happiness inspite of the obstacles.

I find the way the US categorises people racially fascinating (the tendency throughout the EU is to categorise people according to nationality) – e.g. Black, White and Hispanic. The latter is particularly mystifying as over here as to be Spanish would be seen as being white/caucasian – ie, you do not have to be literally ‘white’ to be white. Ged and his fellow islanders could just as easily be the fantasy equivalent of Spanish or Italian. Keep in mind too that fair-haired barbarians were a big problem for the Romans.

Which makes me wonder: If Le Guin is trying to make a point about race, and the characters’ skin colour is intended to suggest a non-European race, then why does the world they inhabit have such a European vibe? Much as I like her, Le Guin does something similar in ‘Threshold’. She mentions that the world’s inhabitants are dark-skinned, but this plays no meaningful role in the story – in every other respect, it’s a typical pseudo-medieval culture. It’s a bit like Dumbledore being Gay.

Re ‘Tehanu’. Funnily enough (as I’ve said elsewhere) I now reckon ‘The Tombs of Atuan’ is the best of the original trilogy, but couldn’t finish ‘Tehanu’. I’d agree with Princess Roxana – I’m not sure substituting one set of gender-based tropes for a new set of gender-based tropes is necessarily progress. In fairness, acquaintances say it and subsequent books are well worth checking out.

That’s it exactly. Making men evil and wrong, or at best misguided and weak in order to build up women as the special, enlightened sex doesn’t appeal to me.

@19. I guess it could have to do with the fact that, unlike the previous trilogy, it is NOT high fantasy anymore.

It deals with what happens to Ged and Tenar after their epic stories are done. They are no longer young or powerful; Ged is not even a mage anymore. We learn of their day-to-day existence –in a farm–, so it mostly reads like a realistic account of life in the countryside. The whole thing is not even anticlimactic –it is a 250-page anticlimax.

It shows the same issues (or qualities, depending on how you look at it) as most of later-period Le Guin production. Many more female protagonists, lots of social themes, but the rich imagination and the vibrant myths from her earlier books are largely absent. You could strip stories like “Old Music and the Slave Women” of their tenuous SF setting and they could be just as easily set in the American South, or Africa, or some regions of Asia.

I did like Tehanu, and its ending promised a much better sequel that sadly never came. Well, I mean, the sequel did come, but it was a big letdown, for me at least.

In the end, it is what it is. Authors don’t owe us new books, or better books, or whatever; they don’t owe us anything at all. (As George R. R. Martin has made abundantly clear, by the way.) We are lucky that Ursula K. Le Guin existed, that she wrote so many amazing books, and that she made her voice heard to the very end. She was an extremely prolific author, and the fact that there are highs and lows in that abundant production is just to be expected. And Le Guin at her worst and less compelling is still miles above many others.

‘You could strip stories like “Old Music and the Slave Women” of their tenuous SF setting and they could be just as easily set in the American South, or Africa, or some regions of Asia.’

Totally. You could say the same about ‘The Dispossessed’.

What @23 Ashgrove said ^^.

“Tehanu” is set in a world completely consistent with the older books, it’s just a very different kind of story about very different kinds of people and situations. (A couple of them are the same characters, but changed greatly: Ged lost his power and status and Tenar walked away from hers, which was a clever way to tell such a very different story with characters we already knew). I loved it; if you’re a fan of high fantasy but dislike “realistic” fiction, you probably didn’t. Each their own. “The Other Wind,” although lyrical and at least thought-provoking in places – LeGuin couldn’t write something that wasn’t if she tried – was more problematic to me in that it seemed to upend some of the underpinnings of the original trilogy.

S

@24/Aonghus Fallon: You just mentioned two of my favourite Le Guin stories. I guess I have a thing for realism in science fiction.

Personally I would have enjoyed a story of Ged adjusting to life without power and getting back to his farmer, shepherd roots helped by Tenar who has already gone through it. It was the painful ideological content that killed it for me.

@21

Spaniards are probably considered “white” in USian terms. I know a 100% Mexican woman who is very pale, speaks English with no accent, and is thus “white” even though born and raised in Mexico to Mexican parents. Many Cubans in or from Florida are effectively considered, in cultural terms, white. My understanding is that skin color is important in Mexico and among the Cuban diaspora in the US, but a different kind of importance than among white Americans.

“I find the way the US categorises people racially fascinating (the tendency throughout the EU is to categorise people according to nationality) – e.g. Black, White and Hispanic. The latter is particularly mystifying as over here as to be Spanish would be seen as being white/caucasian – ie, you do not have to be literally ‘white’ to be white.”

Ditto.

As a person of European descent (Basque, German and Irish) who grew up white in a Latin American country, it was a shock to me when, upon my arrival in the States, I suddenly and magically ceased to be white. Even more puzzling is that white Americans remark to me all the time, “But you don’t look Hispanic!”

But you have to remember that this is a country where, as late as the 1950s, the Irish and the Italians were NOT considered white, no matter how pasty.

(And of course the whole black-white-colored thing is just a colonial fiction dreamed up in a hurry to justify slavery, but that’s neither here nor there.)

“Personally I would have enjoyed a story of Ged adjusting to life without power and getting back to his farmer, shepherd roots helped by Tenar who has already gone through it. It was the painful ideological content that killed it for me.”

IMHO, the growing overemphasis on social issues and “writing like a woman” (whatever that means) took an increasingly heavy toll on Le Guin’s writing.

That’s really interesting Ashgove – in fairness, I don’t think the US is unique in having some very strange ideas about race and ethnicity. I always found the hispanic thing particularly weird, though.

My impression is that Le Guin felt she had to make some sort of reparation for the peripheral role of women in the early books, which I’m not sure was a great starting point. But I also think the original trilogy and ‘Tehanu’ are very much products of the respective periods in which they were written, and would have been very different anyway, given the time-gap.

“My impression is that Le Guin felt she had to make some sort of reparation for the peripheral role of women in the early books, which I’m not sure was a great starting point. But I also think the original trilogy and ‘Tehanu’ are very much products of the respective periods in which they were written, and would have been very different anyway, given the time-gap.”

I completely agree with both statements.

As for the first one –alas, as they say, the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

“in fairness, I don’t think the US is unique in having some very strange ideas about race and ethnicity. I always found the hispanic thing particularly weird, though.”

True. To be fair, it was the French who came up with the saying “Africa begins at the Pyrenees.”

And I remember watching the movie Elizabeth (the one with Cate Blanchett) and laughing when they depict the Spanish ambassador as some kind of Arab. Spanish aristocracy was lily white, and still is. But then again, Elizabeth was alternate history, right? I mean, that’s the only possible explanation for that movie.

‘And then there’s “non-white”: where does that start – Naples?

– something the Irish author Anne Enright said a while back when reviewing a book by Martin Amis (he was talking about ‘non-white foreigners’, of all things). Well, I laughed!

‘And then there’s “non-white”: where does that start – Naples?’

I actually checked up her essay, and it’s frigging hilarious!

Le Guin did explore the issue of gender in “The Left Hand of Darkness” – an adult novel. (One that met with a good deal of controversy at the time.) She later explored gender and gender roles – in her beautiful prose – in the short story collections set in Earthsea. Frankly, expecting the tropes of the “norm” for gender to be “exploded” in a youth novel written in the 1960s is unrealistic. Never the less, the original Earthsea series and “Tehanu” remains a classic in fantasy. If she were with us and writing, we would expect courageous prose on these very subjects.

Seconding the author’s love of Saga and Monstress, Monstress‘s art is so lush and beautiful that you might almost forget the savagery the characters inflict on one another (excepting the Esteemed Professor Tam Tam, of course).

For all the pomp and imaginativeness of its worlds, a great deal of fantasy of A Wizard of Earthsea’s era skewed conservative at its core, able to imagine orcs and dragons but scarcely able to envision relationships that defied the tropes of a heterosexual nuclear family.

Actually, some people seem to think the former justifies the latter. For example, when people in one of my Wheel of Time Facebook groups post to say that they would have liked more LGBT+ people in those books and found the paucity of them unrealistic, one of the jeers they often get is basically “In a story of magic and monsters, that’s the ‘unrealistic’ thing you complain about?”

@@@@@ 34, Aonghus Fallon:

‘And then there’s “non-white”: where does that start – Naples?

I knew someone from Tuscany who swore to it, hammer and tongs, that anyone south of Rome was a baptized Arab.

I do think it’s ironic that after all this time, that the most remembered characters of Asimov include Dr. Susan Calvin and R. Daneel Olivaw…

Aonghus Fallon & Ashgrove– You know that the US classifications/fixation with race is not something we made up ourselves, right? It’s our heritage from our terrible ancestors. As an example, the concept of ‘Hispanic’ was bequeathed to us by Richard Nixon.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hispanic%E2%80%93Latino_naming_dispute#History

I just wanted to add that both “Tombs of Atuan” and “Tehanu” challenge the idea that this series as a whole is uncritical of genre sexism. I personally loved both books. In the original sequel to “A Wizard of Earthsea”, almost all of the characters are women, and Tenar is depicted as powerful, intelligent, and capable in her own right. She rescues Ged as much as he rescues her, and he treats her with respect and honor. In “Tenhanu” – which was written many years later, an older Tenar reflects rather directly on the sexism of the world LeGuin originally envisioned. It’s a too rare peek into the inner lives and struggles of characters who are almost always silent, passive, and sidelined in fantasy.

Ursula LeGuin was the daughter of anthropologists, who specialized in Native Americans, that almost certainly influenced her. As we all know Real World examples of true gender egalitarianism are few to say the least and far from ideal societies make for good stories.

The contrast between Ged’s coming of age story and Tenar’s is interesting and informative. Both are given a position of power young, Ged is responsible for his own problems through misusing that power. Tenar’s power comes at the price of losing herself but she struggles from the beginning against that loss and against the wrongness she senses under her status and power. Get needs to find humility and embrace his flawed self. Tenar muat fight her way through lies to truth. She gives up power and prestige to be Tenar.

I can’t defend it in terms of literary criticism. Not without more research than I’m prepared to do. But I’d debate it over a beer.…

LeGuine’s family connection with Ishi was an underlying shaper of Tombs of Atuan. Ishi lived in secret, enduring loss after loss until he was alone and despaired of life. He wandered into the lowlands, expected the white men to kill him. Instead he was whisked into entirely different world. He spent the rest of his life at U.C. Berkley, with the protection and support of the Krobers. That has to have influenced young Ursula.

Ishi in Two Worlds isn’t a carbon copy of Tehanu’s story. But the archetypal resonances are strong.

Now that’s an interesting thought, it never occurred to me to seek parallels between Ishi’s story and Tehanu.

With regard to Asimov, I was surprised on my recent re-read of his Robot/Empire/Foundation series that he featured more strong female protagonists than I thought he would, based on his reputation. Other commenters have mentioned Susan Calvin, though she fit very much into the old gender stereotype that a woman had to be unattractive and sexless to be successful in an intellectual field, and her debut story was driven by her unrequited love for a colleague. But I was more struck by Bayta Darrell, the heroine of “The Mule” and the one person able to overcome the title villain. There’s also the tough, plucky princess Artemisia in The Stars, Like Dust. And Lije Baley’s wife is more than just a passive helpmeet. Meanwhile, in The End of Eternity (which may or may not be part of the same series depending on how you interpret the nod to it in one of the later novels), Noys Lambent is initially presented as a very sexualized love interest (from an era when women wear translucent clothing), but turns out to have hidden depths and to be far more capable and in control than she appears. Indeed, I would argue that Noys is the true protagonist of the novel, since the viewpoint character who thinks he’s the protagonist is actually a misguided jerk who has to unlearn all his assumptions.

Asimov could be subtly progressive on race too. In The Currents of Space from 1952, I was surprised when it was established that the supporting character Dr. Junz had deep brown skin, and that both very dark and very light skin were equally rare in the galaxy, with most humans being intermediate shades of brown. There’s also a bit of subversive commentary when Junz idly wonders why ancient English had a “special word” for people with dark skin, when there was no special word for blue-eyed or large-eared people or other such inconsequential physical traits.

By the same token, the Spacers in the Baley/Olivaw novels were described as bronze-skinned, and though that could’ve been taken to mean they were just well-tanned white people (which is probably how he got away with it), in the context of what Currents reveals, we can safely assume that most of the characters in the Robot, Empire, and Foundation novels are actually nonwhite — a nice counterargument against anyone who’s inclined to complain about the casting in the Foundation TV series.