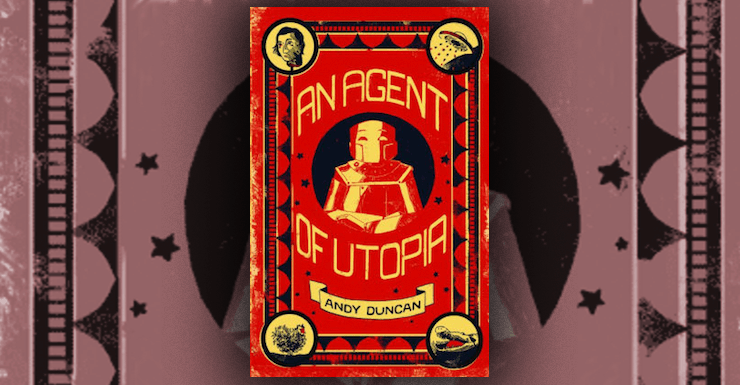

Andy Duncan may not be the fastest or the most best-known writer in science fiction and fantasy, but he’s one of the best. His books might not fill an entire shelf—he’s published just two prior collections and a handful of chapbooks—but the awards he’s won, including a Sturgeon Award, a Nebula, and three World Fantasies, could easily fill a bookcase. His first two collections, The Pottawatomie Giant and Beluthahatchie, are currently out of print, so Small Beer Press’s publication of An Agent of Utopia: New & Selected Stories, is an occasion to celebrate, and cause to hope that this fine writer finds a broader audience.

The title story of the new collection is, oddly enough, perhaps the least characteristic in the collection. “An Agent of Utopia” is the report of a nameless assassin, sent to Henry VIII’s England from the Utopia of Sir Thomas More. Our poor narrator fails to rescue the sainted Sir Thomas, and is eventually tasked by his daughter with recovering the great man’s head from London Bridge’s Stone Gate. Things get messy. “An Agent of Utopia” is a satisfying story, but its historical European setting is surprising from Duncan, a writer most often concerned with America and its South.

Even those stories set elsewhere tend to be about America and its history. “The Big Rock Candy Mountain,” for example, is set in the hobo paradise of the folk song, complete with cigarette trees, lemonade springs, cops with wooden legs, and jails made of tin. In “Beluthahatchie,” we learn that Hell isn’t too different from the more barren parts of the South and the devil not too different from a white planter. Even the most far-flung of these stories, “Senator Bilbo,” about a bigoted Baggins descendant, moves contemporary American concerns about walls, borders, and migrants to a version of Middle-Earth that seems to come by way of Discworld. That story’s probably the weakest in the collection, but the evanescent visions of better world in “Joe Diabo’s Farewell” and “The Pottawatomie Giant” will stay with me, as will the confused, wistful yearning of “The Maps to the Homes of the Stars” and the ludicrous grace of “Unique Chicken Goes in Reverse.” And the final story in the collection, the award-winning “Close Encounters” may be the best science fiction story I read this year.

In emphasizing Duncan’s undeniable Americanness, I run the risk of neglecting his range of plot, character, and historical reference. In addition to already mentioned appearances by racist hobbits, St. Thomas More, and the devil, Duncan’s stories feature, amongst others, the “Great White Hope” who defeated black boxer Jack Johnson, Zora Neale Hurston, a Haitian zombie, a 1930s Native American steelworker, multiple voodoo loa, a vegetarian priest, the king of the hobos, Flannery O’Connor, and a chicken named Jesus Christ. There’s also a one-line cameo from the Marx Brothers.

Duncan’s love of Americana, his Southern twang, his high concepts masterfully brought to earth, and his dense concision—novels’ worth of research condensed into a story of twenty or thirty pages—remind me of no one so much as Howard Waldrop, another master of high-concept short fiction kept in print by Small Beer Press. Like Waldrop, Duncan recognizes the beauty of vernacular speech; like Waldrop, his writing calls mind the best porch-front jawing and tale-telling you’ve ever heard:

They all turned and looked at him, and friend, he wasn’t much to look at. Cliffert was built like a fence post, and a rickety post, too, maybe that last post standing of the old fence in back of the gas station, the one with the lone snipped rusty barbed-wire curl, the one the bobwhites wouldn’t nest in, because the men liked to shoot at it for target practice.

Buy the Book

An Agent of Utopia

And he’s wryly funny. Here is a priest reflecting on chickens:

He liked chickens when they were fried, baked or, with dumplings, boiled, but he always disliked chickens at their earlier, pre-kitchen stage, as creatures. He conceded them a role in God’s creation purely for their utility to man. Father Leggett tended to respect things on the basis of their demonstrated intelligence, and on that universal ladder chickens tended to roost rather low. A farmer once told him that hundreds of chickens could drown during a single rainstorm because they kept gawking at the clouds with their beaks open until they filled with water like jugs.

If you only tolerate straight exposition and terse summation, you’re unlikely to become a Duncan fan, but if this sort of chewy prose appeals to you, you will love this collection.

If you’ve never read Duncan before—I’ll admit I only knew him by reputation before reading this collection—you can skip this paragraph. If you’re one of the lucky few to have read his previous collections, you may want to know the balance offered between “New” and “Selected” stories. Since those previous collections are relatively difficult to find today and since Duncan clearly values quality of writing over quantity of output, it’s not surprising that most of the stories in An Agent of Utopia have appeared in previous Duncan collections. Only the title story and “Joe Diabo’s Farewell” are original to this collection, and, of the remaining stories, only the brief tall tale “Slow as a Bullet” is previously uncollected.

An Agent of Utopia must rank as one of this year’s best collections. It’s on bookstore shelves now and deserves to be on your shelves soon. As for me, I’m off to hunt for Andy Duncan’s previous collections.

An Agent of Utopia is available from Small Beer Press.

Matt Keeley reads too much and watches too many movies. You can find him on Twitter at @mattkeeley.