As you’ve probably heard, Amazon has announced that it’s producing a show set in Middle-earth, the world created by J.R.R. Tolkien in his landmark novels The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. With the new series reportedly headed into production in 2019, I thought it was time to revisit the various TV and big screen takes on Tolkien’s work that have appeared—with varying quality and results—over the last forty years.

Today we finish our look at Ralph Bakshi’s feature-length animated The Lord of the Rings, released in November 1978. The first half of the movie is discussed here.

When last we left our heroes, Boromir had been turned into a pin cushion by the Orcs, Frodo and Sam were simply kayaking into Mordor, and Legolas, Gimli, and Aragorn had decided to let Frodo go, and headed off to rescue Merry and Pippin.

Bakshi’s The Lord of the Rings was originally titled The Lord of the Rings, Part 1, but the studio made him drop the “Part 1” subtitle as they believed nobody would show up for half a movie. This is, of course, ludicrous. These days movie studios gleefully divide movies into Parts 1 and 2 to milk more money out of franchises. Hell, roughly half the planet showed up to Avengers: Infinity War (itself originally sub-subtitled “Part 1”), despite many people knowing it would end with a cliffhanger to be resolved in Avengers 4. Then again, back in 1978, even Star Wars wasn’t “Episode IV” yet. Like the One Ring in The Hobbit, nobody quite knew what they had their hands on yet.

Sadly, despite making good money at the box office, Bakshi never got to make Part 2. So we’re left with only his adaptation of The Fellowship of the Ring and The Two Towers in this one movie. It makes the film feel both overstuffed (it’s oddly jarring when the movie doesn’t end with the Breaking of the Fellowship) and undercooked (every scene after the Mines of Moria feels rushed).

It’s a shame, too, because Bakshi’s art is gorgeous and his adaptation choices are superb. What wonders he would have done with Mordor, Minas Tirith, Faramir, Denethor, and the Scouring of the Shire! For all the talk about Guillermo del Toro’s aborted Hobbit movies, I think The Lord of the Rings, Part 2 is the greatest Middle-earth movie never made. It’s the second breakfast we never got to eat.

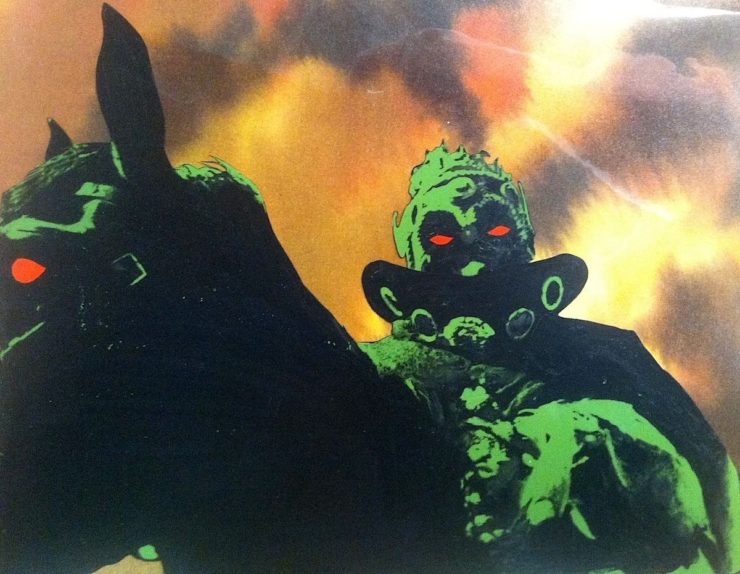

Still, all we have to decide is what to do with the movie that is given to us. And The Two Towers part of Bakshi’s movie has plenty to recommend it. We begin with Boromir finally getting the Viking funeral he clearly dressed for, and Frodo and Sam paddling down the River Anduin pursued by Gollum on a log. Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli run off in pursuit of the rotoscoped Orcs who’ve captured Merry and Pippin.

While most of the movie’s scenes after the Mines of Moria feel too short, Bakshi does give us a scene even Peter Jackson left out, where Pippin helps instigate their escape by insinuating to a Mordor Orc that he has the One Ring. It’s one of my favorite scenes in the book, because it’s the moment where “Fool of a Took” Pippin shows that he’s not a dimwit, he’s just young and naive. While it’s less spelled out here in the film, it’s also the first moment in The Lord of the Rings that shows the Orcs aren’t a bunch of murderous dimwits either. They have their own agendas and loyalties. Grishnákh, the Orc who accosts Merry and Pippin, isn’t a mere foot soldier. He’s high-ranking enough to know about the Ring and who bears it, and even its history with Gollum: all things Pippin is canny enough to exploit. (After this, Merry and Pippin don’t get much to do in Bakshi’s movie, but here we get a hint of where their stories might have gone in Part 2. More than anything, I’m sad we don’t get to see their complex relationships with Théoden and Denethor.)

Buy the Book

The Ruin of Kings

But real salvation comes in the form of the Riders of Rohan, who are entirely rotoscoped. They mow down the Orcs and Merry and Pippin manage to escape into Fangorn Forest, where they hear a mysterious voice. It turns out to be the Ent Treebeard, but we don’t get much of him save for him carrying the two hobbits around the forest (while they clap merrily). Treebeard is very cartoony. He looks like the Lorax in a tree costume and has small legs and even a cute butt. (I found myself thinking far too much about Ent butts while watching this movie, and then every day thereafter. And now, so shall you.)

MEANWHILE…Frodo and Sam are lost, though somehow close enough to spot Mount Doom glowing grimly off in the distance. Sam notes that it’s the one place they don’t want to go to, but the one place they have to, and it’s also the one place they just can’t get. It’s a depressing situation, made all the worse by the creeping knowledge that they’re being followed. Finally, Gollum jumps out of the shadows and attacks them, though Frodo gets the upper hand with his sword Sting and the power of the Ring.

Bakshi’s Gollum is a gray, goblin-y creature with a loin cloth and some random hairs. He looks vaguely like a Nosferatu cosplayer who sold all his clothes for weed. But he certainly looks more like a former hobbit than the hideous toad creature in Rankin/Bass’ animated Hobbit. Despite his creepy look and murderous intent, he’s a pathetic creature, drawn and addicted to the Ring that Frodo bears.

Gollum is the most fascinating character in The Lord of the Rings, a morally and literally gray creature who manifests the evil and corruption of the Ring. In Gollum, Frodo can see both what the Ring will do to him eventually, and also what he himself is capable of doing with the Ring. Later, Bakshi has Frodo deliver a line from the book, where Frodo threatens Gollum by telling him that he could put on the Ring and command him to commit suicide—and Gollum would do it. It’s why Frodo is less wary of Gollum than Sam; Frodo knows that he can control Gollum. This represents only a pathetically small fraction of the Ring’s true power to command others, but it does give us a sense of what’s at stake: the power of the Ring is to turn us all into Gollums, whether through its direct corruption, or the sinister control it grants the wearer if they have the will enough to fully wield it.

It’s why Boromir’s desire to wield the Ring is so wrong. It’s not just that its presence changes you, slowly turning you from a crankypants into a full-fledged psychopath with a serious Vitamin D deficiency. It’s that its power—to control and bend the wills of others—is inherently evil. It’s not a sword or some other fantasy MacGuffin that could be wielded for good or for ill. To use the Ring (aside from simply turning invisible) is to commit a terrible, irrevocable crime against others.

Tolkien’s work—and Bakshi’s film beautifully reflects this—is centered on different modes of leadership, and the corruption of power and control. Sauron, Tolkien tells us, was corrupted by his desire for order, his desire for control. He thought the Valar were making a muck of Arda, so he allied with Morgoth, believing a single strong hand could make things right. But, of course, it only led to more chaos. Centuries later, Sauron controls Mordor, but his dominance comes at the cost of his entire realm becoming a horrific wasteland. It’s the same with the Ringwraiths and the Orcs. They’re hideous mockeries of Men and Elves, not only because they’re supposed to be terrifying, but because they could only be so: The only way to control something is to fundamentally break it.

It’s again a shame we never got the completion of Bakshi’s adaptation, because I think that more than any filmmaker who’s taken on Tolkien, he understands that essential theme of Tolkien’s work and how it plays out in the story. I say this, because after discovering that Gandalf is alive and shinier than ever, Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli make for Edoras, capital of Rohan, where they meet King Théoden and his conniving servant, Gríma Wormtongue.

Bakshi’s Wormtongue looks like a hobbit who left the Southfarthing and pursued a career as an adult film director. He wears a black cape and hood and has a thin mustache that practically announces, “I am a slimy jerk.” But what’s fascinating about Bakshi’s portrayal is that he makes Wormtongue short and rotund: in other words, he makes him look like a hobbit.

Wormtongue comes across as a sort of parallel Gollum, and even Frodo. Like Frodo, he pals around with a king (Aragorn/Théoden) and is mentored by one of the Istari (Gandalf/Saruman). But unlike Frodo, who has friends galore in the Shire, Wormtongue is alone. It’s not hard to imagine this short, portly man being bullied and despised growing up in the warrior culture of Rohan. You can imagine how thrilled he was to become an ambassador to Isengard, seat of a powerful wizard and a place where power comes from words and not arms. How easily he must have been seduced by the Voice of Saruman!

Of course, we don’t get this background on Wormtongue in either the books or the movies. But Bakshi’s depiction of the character, either intentionally or not, can give that impression. I hadn’t ever considered interpreting Wormtongue as a sort of parallel Gollum or Frodo, but Bakshi’s interpretation made me realize the possible connections. Which, of course, is the power of adaptation—using different media to bring out elements of a work we might otherwise miss.

The parallel that Bakshi draws between Gollum and Gríma works wonderfully—though, again, the lack of Part 2 means we never get to see the full fruition of that decision with either character. After all, it’s lowly Gollum and Gríma who ultimately destroy the Maiar Sauron and Saruman, years of domination and abuse finally sending them over the edge—literally, in Gollum’s case.

One of the things I’ve always loved about The Lord of the Rings is that Tolkien invokes such great pity for a character type—the sniveling, traitorous weakling—that is normally treated only with contempt. It’s something Bakshi also invokes here, as does Jackson in his Rings movies (and utterly betrays in The Hobbit movies, as I’ll talk about down the line in this series).

Bakshi’s Gollum is as richly realized as Jackson’s, though of course given fewer scenes. We get a similar debate between his good and bad sides, and a confrontation with Sam about his “sneaking.” We leave Frodo and Sam in the same place Jackson does in his Two Towers: following after Gollum through the woods, with Gollum planning to bring the two unsuspecting hobbits to “her.” Along the way, Bakshi gives the borders of Mordor some impressive statuary—creepy colossi that echo the ruins Frodo glimpsed when he put on the Ring way back at Weathertop.

The real climax of The Two Towers section of the movie is the Battle of Helm’s Deep. Bakshi gives the fortress a beautiful high fantasy look, with towering pillared halls. And the march of Saruman’s Orc horde is deeply scary, especially as they sing a low, frightening song. Not to mention the fact that Saruman shoots fireballs all the way from Orthanc that blow apart the fortress’ wall. Aragorn and Company are overwhelmed, but the Orcs are vanquished by the arrival of Gandalf and Éomer (whose role in the movie is essentially one rotoscoped shot of him riding a horse repeated a few times) leading a charge of men against the Orcs.

The film ends with Gandalf triumphantly tossing his sword into the air, with the narrator saying that the forces of darkness have been driven from the land (not quite, Mr. Narrator!) and that this is the end of “the first great tale of the Lord of the Rings.”

Bakshi’s The Lord of the Rings saga may remain forever incomplete, but the half he did make is still a masterpiece: an epic, beautifully-realized vision of Tolkien’s world, characters, and themes, one that can stand proudly alongside Peter Jackson’s live-action Rings movies. It is, I suppose, a halfling of a saga, but like Bilbo, Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin, while it may seem familiar, it’s full of surprises.

Next time, Rankin/Bass returns to Middle-earth to unofficially complete Bakshi’s saga with their animated TV movie The Return of the King.

Austin Gilkeson formerly served as The Toast‘s Tolkien Correspondent, and his writing has also appeared at Catapult and Cast of Wonders. He lives outside Chicago with his wife and son.