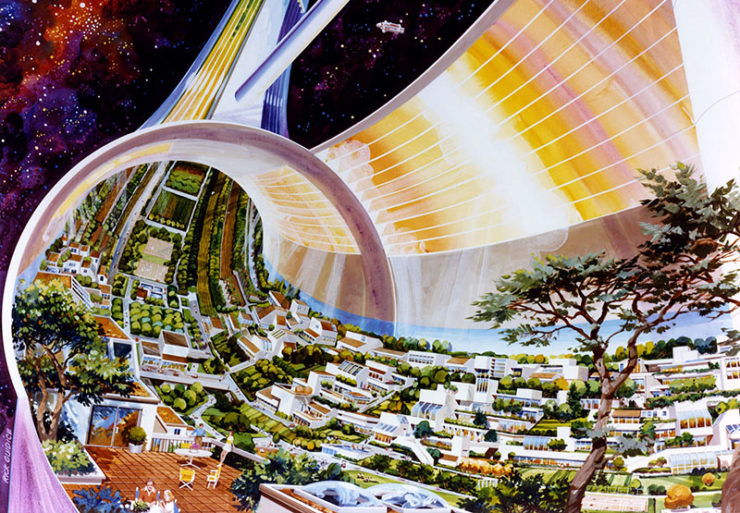

In 1974, Gerard K. O’Neill’s paper “The Colonization of Space” kicked off what ultimately proved to be a short-lived fad for imagining space habitats. None were ever built, but the imagined habitats are interesting as techno dreams that, like our ordinary dreams, express the anxieties of their time1 .

They were inspired by fears of resource shortages (as predicted by the Club of Rome), a population bomb, and the energy crisis of the early 1970s. They were thought to be practical because the American space program, and the space shuttle, would surely provide reliable, cheap access to space. O’Neill proposed that we could avert soaring gas prices, famines, and perhaps even widespread economic collapse by building cities in space. Other visionaries had proposed settling planets; O’Neill believed it would be easier to live in space habitats and exploit the resources of minor bodies like the Earth’s Moon and the asteroids.

Interest in O’Neill’s ideas waned when oil prices collapsed and the shuttle was revealed to have explosive flaws. However, the fad for habitats lasted long enough to inspire a fair number of novels featuring O’Neill-style habitats. Here are some of my favourites.

Ben Bova’s 1978 Colony is set eight years after Bova’s Millennium. The world is unified under a World Government, but the issues that nearly drove the Soviet Union and the United States to war in late 1999 persist. Only a single habitat has been built—Island One, orbiting at the Earth-Moon L4 point2 —and it will not be enough to stave off doomsday. This suits the billionaires who paid for Island One just fine. Their plan is to provoke doomsday, wait it out in Island One, then rebuilt Earth to suit their discerning tastes.

Colony is not without its flaws, chief among them a sexism impressive even for the era in which it was written; Bahjat, one of the few women with agency in the book, is essentially given to protagonist David as a prize at the end of the novel. Still, there’s one element in the setting that endeared the book to me; there is no refuge for malevolent oligarchs that the labouring classes cannot reach … and destroy. All too many SF novels have sided with the oligarchs (let the canaille die!). A book that took the side of the teeming masses was a refreshing change.

As far as I know, John C. McLoughlin only published two novels: The Toolmaker’s Koan (which wrestled with the Fermi Paradox or rather the Great Filter) and his space-habitat book, The Helix and the Sword. Set five millennia after resource shortages, pollution and war have ended the European Ascendancy, an asteroid-based culture finds itself on the brink of a Malthusian crisis like the one that doomed Earth five thousand years earlier.

Malthusian crises, a devastated Earth, and space based civilizations were common features in 1970s and 1980s SF. What makes The Helix and the Sword interesting is its imagined biotechnology, which allows the space-faring humans to grow ships and habitats just as we might grow crops or domestic animals. It’s a pity that the political institutions of the world five thousand years from now have not kept pace with the biotech.

The eponymous Starfarers of Vonda N. McIntyre’s Starfarer Quartet is a habitat (well, a pair of habitats that function as one craft) that is small as space colonies go. But it’s agile and fast: it sports a vast light sail and has access to a handy cosmic string that can take it to the stars. The US government sees it as a potential military resource; the inhabitants hijack it rather than be conscripted. However, they are not prepared for what they find at Tau Ceti.

It’s best not to calculate how many square kilometers of light sail even a small craft would need for even a small acceleration3 , let alone the accelerations Starfarer seems to enjoy.

Starfarer was imagined in a series of panels at Portland’s Orycon convention. It’s interesting as a setting that explores more than tech. McIntyre is interested in relationships other than the male-female pairs assumed by most SF authors.

Set a generation after the welding of Canada, Mexico, the United States, and other nations into a fragile North American Union, Alexis Gilliland’s The Rosinante Trilogy chronicles the end of a golden age, as the space habitat investment bubble suddenly bursts. It features a heavy-handed government, determined to crush dissent even where it does not exist, and engineers who build without asking what the consequences of their inventions might be.

Gilliland’s cheerfully cynical tale is one of very few stories to play with the idea that space habitats might prove as solid an investment as tulips and bitcoins. That alone would have made it memorable. The books are often quite funny. I still relish the memory of the artificial intelligence Skaskash, which invented a religion that was way more successful than it expected.

THERE IS NO GOD BUT GOD AND SKASKASH IS ITS PROPHET!

No doubt those of you of a certain age have your own favourites. Feel free to mention them in comments.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nomineeJames Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.

[1]Cole and Cox’s Islands in Space (1964) thought space colonies might allow humans to escape the certain doom of nuclear apocalypse. Given that they wrote soon after the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962), one can understand why nuclear war might be in their minds. In those days it seemed unthinkable that nation states would be so irresponsible as to create the means to render a significant fraction of the planet uninhabitable and then not use it.

[2]Some of you may wonder if I mean L5 there. Nope! The plutocrats who built Island One preferred the view from L4.

[3]Cosmic strings have been hypothesized but not yet proven. There’s no reason to believe that if they would allow FTL travel if they did exist. This would be an example of a “gimme”, the one implausible idea the author is allowed. Another example: The Forever War’s endearing physics gimmee, the belief that one can fly into a black hole and emerge light years away rather than being smeared into a cloud of quarks.

I’d go for a L3 myself, all the better to avoid prying eyes. If I were a bloodsucking techbro billionaire anyway.

From a certain point of view, Neal Stephenson’s Seveneves features a thrilling space habitat.

My introduction to Tom Swift (aside from terrible puns in Boy’s Life) was from the revival series published in the early 80’s. I believe the first book The City In the Stars was partially set on an O’Neill style colony. IIRC at one point the hull of the colony is punctured, and it’s pointed that while it’s a problem, it would take several days for the colony to decompress to the pointo f endangering life.

Short-lived in western prose, perhaps, but space habitats (called “colonies”) have been a fixture of Japan’s Gundam franchise since its origins in 1979, usually standing as the source of an independence movement that triggers the war that drives each series, and often dropped as a continent-destroying superweapon.

Notable examples include the five overdeveloped Stanford Torii that each produced one of the five hero Gundams from Wing, the O’Neill cylinder that gets destroyed in the first episode of SEED (setting the refugees on their path to heroism), the O’Neill cylinders visited by the Iron-Blooded Orphans (in which we get to see a terrorist bombing “over there” as the characters look up over their heads), the fancy, alien-looking Martian-made Bernal sphere in AGE, and Reconguista‘s Towasanga: five parallel Stanford Torii wrapped around an asteroid like rings on a bony finger.

I suppose we’re looking at “county in the sky” scale of construction, and self-sustaining, not a Mir outpost. ;-) And not “Venus Equilateral”… or maybe yes? They have a hydroponic farm and natural air production but they’re still a company town.

Then there was “The Lost Cometary Colony”, which kind of gives away the end of the story… except for where it went.

One of the first SF novels I read was Lester Del Rey’s “Step to the Stars” which featured a space station.

I don’t know why that double posted….

Alexis Gilliland has an unpublished novel set in a Solar System that has solved the life support problem but not the absurdly powered one gee forever problem, with the result there are billions of people living in space but it takes them years to get around the Solar System. I hope it sees print at some point.

I heard him read from a prequel story (about two crooked officers’ reaction to the revelation that a subordinate listed ‘forensic accounting’ as a hobby). During the discussion he mentioned offhandedly one could comfortably fit the population of Texas into a surprisingly small volume. A quick calculation says 30 million Texans at a tenth of cubic meter each is only a cube 145 m on an edge! Although they might want room to move, which would require more volume. Still, even at 10 m^3 each, you could fit the entire population of Texas into a cube well under a kilometer on an edge. There are lots and lots of rocks that big in the belt.

Space stations are a set of which habitats are a small subset. Not sure where I’d draw the line.

The del Rey was a Winston, as I recall. Thunderchild is reprinting many (or maybe all) of those.

More seriously, my two favorites are probably Pell Station (a.k.a. Downbelow), from C.J. Cherryh’s Downbelow Station & Alliance/Union novels, and Meetpoint Station from the related Chanur novels.

Although I’m not sure where they’d fall on the station/habitat continuum.

There’s the Near Space series by Allen Steele (Orbital Decay, Lunar Descent, Clark County). Interesting because I’ve read them each 3 times and I still can’t decide if I like them or like to dislike them.

Cherryh calls her stations stations, and they need input from a planetary biosphere, and IIRC they *feel* like ‘stations’ (corridors), but I think they have population of habitats (~100-250,000). Though even then the entire space population would fit into one medium Third World city on Earth.

Bujold has Kline Station, a self-sustaining station-habitat (again, feels more ‘indoors’ than an O’Neill colony) built to exploit a wormhole nexus. Her quaddies live a bunch of habitats in a planet-less system.

Babylon-5 was a station with O’Neill attributes (like rotating gravity, a big ‘outdoor’ area and big population) that I assume wasn’t designed to be a full habitat.

Ringworld is like the ultimate space habitat. Banks Orbitals are slightly less impossible and not a lost technology.

The Abh of “Crest of the Stars” live in habitats and ships, especially one big habitat where they have kids.

Macross Frontier is based on something straddling the fine line between “mobile habitat” and “FTL generation ship”. There are a bunch of other such colony ships.

The Coven, described in the second novel of John Varley’s Gaea trilogy, is one of the few long-term successful space habitats in the L5 point – but apparently groups keep showing up and buying a second-hand habitat and then mostly dying off or leaving in a few years.

I was a bit surprised when in the course of reading Regenesis I realized the whole of Union had about as many people as modern day New Zealand, yet somehow was able to match Earth, which presumably has a lot more people than modern day Enn Zed.

Would Ringworlds count?

The ship in Gene Wolfe’s Book of the Long Sun might qualify? It’s certainly big, self-sustaining and has wide open spaces …

Captive Universe by Harry Harrison had one of those asteroid-based cylinder habitats, used as a generation ship. I think it may have named Eros as the asteroid in question. I guess using it as a generation ship disqualifies it from this article.

Most of the action in Enders Game takes place on an O’Neill cylinder (Battle School).

Lifeline is a near future SF novel set on a number of space colonies. Very hard technical SF.

You didnt mention Niven’s Ringworld trilogy.

Although discovered by but not built by space fairing humans, the Ringworld was built by a mysteriously lost and forgotten ancient race of engineers.

I cant say for sure but it seems to me that Niven’s idea behind Ringworld may have been sold/bought or even stolen by the brains behind the Halo game developers.

Nobody’s mentioned Iain M. Banks’ Culture habitats? With seas, mountains, bullet trains, pine forests, deserts, the works, if I remember correctly.

Speaking of games, there’s a funny example in Mass Effect: Andromeda. The player character is desperately trying to find or create habitable land on planets in the Andromeda Galaxy, for about 150,000 colonists. They work out of a space station the size of Manhattan, complete with spin gravity and extensive green spaces. Just staying on the station doesn’t seem to occur to them.

In my own mind, I always divided space stations, which were oriented towards specific tasks or functions, from space habitats, which were places where lots of people lived. Space stations might or might not spin for artificial gravity, and some people could live there, but habitats always spun, and always had inhabitants, families, schools, and all the trappings of big city civilization. But that is just personal, I don’t think anyone ever really standardized the terms.

My favorite space habitat is described here, in the opening lines of the script, “It was the dawn of the third age of mankind, ten years after the Earth/Minbari war. The Babylon Project was a dream given form. Its goal: to prevent another war by creating a place where humans and aliens could work out their differences peacefully. It’s a port of call, home away from home for diplomats, hustlers, entrepreneurs, and wanderers. Humans and aliens wrapped in two million, five hundred thousand tons of spinning metal, all alone in the night. It can be a dangerous place, but it’s our last best hope for peace. This is the story of the last of the Babylon stations. The year is 2258. The name of the place is Babylon 5.”

@13 Union is a heavily “maritime” power with a tech advantage in producing trained space crews fast (and probably legal advantage, assuming slavery and cloning and brainwashing are still restricted on Earth). Earth is mostly inclined to write off the colonies as a bad investment (true from its perspective) and not supporting its fleet, and even so the Mazianni are nevertheless a terror. And the dangerous prospect of its actually extending a fraction of its attention again drives the events of Downbelow Station.

I think the situation is at least reasonably plausible long as the spacers aren’t seen as an existential threat to Earth or a huge cash cow.

Wow I miss those NASA illustrations. They, along with some of the Usborne books, made a huge impression on me as a child and coloured forever the way I would envision the future.

No one has mentioned DS9, although Bab5 was mentioned.

Two more votes for Allen Steele’s Near Earth series and John Varley’s Gaea trilogy. I liked the latter enough to try my hand at a 3D model of Gaea.

Cherryh: I think Heavy Time or Hellburner say Earth has 10 billion people. I’d estimated 100 stations at 100,000 people for 10 million spacers. Though Union does have the planet Cyteen and mass-produced azi, so its population was less boundable than Alliance’s (Regenesis being a late book.)

24: I like your perspective, and it makes sense; OTOH I also recall spacers going independent causing an economic downturn on Earth, and part of what drives the conflict is Union supposedly attracting scientists and outcompeting Earth in development. It’s been a long time since I read those books but I got a strong sense of “Earth has teeming useless billions, vs. the Brave Pioneers of Spaaace.”

The design for DS9 came from the artist forgetting that the Star Trek setting had artificial gravity, so he drew it as an arrangement of wheels for spin gravity. It looked good enough that they kept the circular design, but just broke some of the wheels into arcs.

The Scientific People had cobbled together a pretty interesting habitat in ‘The Stars My Destination’ – is there really a difference between spin-flating a solar-mirror melted asteroid, and welding crashed spaceships together around a nickel-iron rock?

The Ringworlds (you know there’s more than one, right) were built by Pak as part of their solution to the core explosion. Sadly we don’t have any idea who caused that…

it wasn’t humans that discovered the one in the Ringworld stories; it was Pupeteers, who almost immediately loosed (at least) the viroid that destroyed the floating cities by eating the superconducting materials.

And, no, I don’t agree that the drop in oil prices was what reduced interest in space colonies. That was more to do with the USA losing the will to do anything interesting.

And nobody has yet mentioned the space colony – O’Neil iirc – at the centre of the action in Neuromancer?

I always thought O’Neil took the basic shape for his cylinders from Rendevous With Rama. I could be wrong … but I doubt it.

Cybersnark @@.-@:

Torii may seem appropriate for a Japanese series, but the plural of “torus” is “tori” (or “toruses”).

Nargun @31:

Rendezvous with Rama was published in 1973. O’Neill’s first publication of the cylindrical colony idea seems to have been in “The Colonization of Space“, published in Physics Today in 1974. However, by O’Neill’s own account he had been trying to get the paper published since 1970, with many of his ideas about space colonization originating from work with students in a physics course he taught at Princeton in 1969. (In any case, once you start thinking about simulating gravity by rotating a structure in space, a cylinder is one of a few obvious options.)

@30 Even without an economic downturn, the O’Neill colonies were doomed to failure. His calculations were way, way too optimistic. And building reusable spaceships and bringing down the cost to orbit turned out to be far more challenging than anyone thought it would be. If I had a dime for every time a pie in the sky concept from Popular Science didn’t come to fruition back in those days, perhaps I could have funded my own space program.

@24/27 — I’m a short ways into Alliance Rising (Cherryh’s brand new Union/Alliance novel, and the earliest in the sequence), and it sounds like one issue for Earth is that in the early days of FTL, Earth proper wasn’t actually FTL-accessible — they hadn’t identified any local masses they could use for intermediate jump points, and the distance from Earth to Alpha (the nearest station) was too far for a single jump, at least with the existing technology. So Earth was still using STL “pusher” ships to reach Alpha, at which point people or goods could transfer to FTL ships to reach the newer stations.

(Having said which, I think this is the first I’ve heard about Earth being cut off from everybody else in this way?)

I’m a fan of Gilliland’s Rosinante Trilogy, not so much for the habitats or the action as for the treatment of the AI characters. They’re basically people, not terminators, Number Five, or Colossus/Guardian. Sure, they’re computers with a few extra abilities, but they act and sound like regular old human beings. Isn’t that what we hope our AI systems will do eventually?

The interesting thought is that the AI systems will replace the bureaucracy that stands between the Governor/King/President and his people, eliminating most of its flaws and difficulties. Imagine a fully-automated and instantly-reacting DMV.

“Worlds” and “Worlds Apart” by Joe Haldeman are my favorites, and I really enjoyed Michael Flynn’s “Firestar” series for how he built his world(s) from scratch: One dream and all the steps necessary to get from here… to there.

Greg Bear’s Eon series?

Ah, I haven’t read Eon in 19 years. I should put it on the list for Big Hair, Big Guns….

There was also Hinz’ Paratwa saga, which provided me with an enormous moment of hilarity a few years back when someone else compared a pair of people who greatly complicated my life to the paratwa. The pair thought it was a compliment, not being familiar with 1980s SF…

random22 (1): do you mean L2 (behind the Moon)?

AlanBrown (23): Did B5 ever say what “third age” meant? (I missed the last season.)

ngögam (32): Any fool knows that all Latin nouns, of every declension, have plurals in –ii.

@34. – Asimov’s detective novels, “Caves of Steel”, “The Naked Sun”, and “Robots of Dawn” had earth as a backwater planet, sort of a neglected stepchild that spacers and their robots tended to look down upon.

And @31/@32 – I’m glad that SOMEBODY mentioned “Rama”! <grin> Clarke seemed very good at extrapolation, and his Rama stuff was no exception.

You can read the original paper by O’Neill here (click on the pdf download button).

https://physicstoday.scitation.org/doi/abs/10.1063/1.3069151

Paul

Tamfang (39): If IIRC the Third Age started with Earths access to the interstellar gates. Again, IIRC, background info from JMS from the lists he was active on at the time.

Oops, the above link is a letter in response to it. Its this one.

https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3128863

Paul

I’m trying to remember a novel I read late 70s-early 80s, and I’m pretty sure it wasn’t published much earlier than that, but my memory is faulty. It was about a discovered world, a Dyson Sphere type. I think the author’s last name began with an R but I’m probably wrong about that, might have been the first name. Whoever it was, I don’t think I ever saw any other books by them. I’ve been through the whole R section at Fantastic Fiction, plus read the Space Habitat, Dyson Sphere, and Hollow World entries of the SF Encyclopedia. The title might have been something like The World Is Hollow, but a search for that at FF didn’t produce the right results either. I can even visualize the cover image, but apparently not the correct title. Does anyone else have a clue?

Cities in Flight, James Blish. Why build when you can just lift the whole thing?

Tony Rothman was the author. I think the title was The World is Round. Del Rey books, late 1970s.

Thanks, James. That’s it. I recall it was an okay book, but apparently not good enough for me to hang on to it. He does not have a listing at Fantastic Fiction, although amazon shows a few used copies.

Where does Asimov’s Trantor fit into this? It started as a planet but devolved into a world covered completely with metal buildings save for the relatively imperial reserve. It produced nothing but law and relied on other planets in the empire for food, manufactured goods and so on. In a psychohistorical sense, it was a world turned into a space station and then, as the empire collapsed, turned back into a world. Viewed from the physical science view, Trantor was always a world, but Seldon knew better.

Also, what about Heinlein’s moon colony in The Menace From Earth. It’s not free floating, but it is suitably artificial. The story was out of one of Simon and Kirby’s romance comics, but more enlightened.

For an unusual take, check out The Planet Strappers. If nothing else it is different and presents a surprisingly negative view of planetary life when compared to space colony and asteroid life. The earth is a dead end. Mercury with its narrow inhabitable strip is too limited. The moon is controlled by the mob. Mars has been taken over by alien plants. Jupiter and Saturn are too far and too cold. The future of human life is in the asteroid belt, the remains of a planet destroyed in an ancient war. It’s SF technology was conventional for its day, but it is a surprisingly bleak vision.

There’s been so many great space habitat examples here, so I think I’ll add a few more that made a big impression on me:

National Geographic published a fictional article on an L5 colony, complete with those lush, amazing illustrations (like the one above); this would have been sometime in the late 1970s.

Vonda McIntyre’s Supraliminal included several great habitats (underwater and in space).

Frederick Pohl’s HeeChee series are mostly set on Gateway, a hollowed-out asteroid built originally by a long-gone alien race that’s become a prospector’s dream/nightmare. People fly out in alien spacecraft, cross their fingers, and either come back rich, hurt terribly, or dead (or never come back). It’s a problematic series of books, but

The various habitats and stations in William Gibson’s short stories (“Red Star, Winter Orbit”, “Hinterlands”) were beautifully detailed.

Heinlein’s Orphans of the Sky.

The generation ship, Vanguard, could be classed as a habitat. This (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orphans_of_the_Sky) states it is the first fictional generation ship.

Really liked the character Joe-Jim

The first habitat that comes to mind is Tranquility from Peter F Hamiltons Nights Dawn trilogy.

And also the Raiel High Angel ark ship from his Commonwealth books serve as a habitat to 15 million humans and aliens.

And maybe the Olyix ark ship from his Salvation book(s) counts as well.

James Blish wrote a great series called Cities in Flight that holds up well enough 40 years or so after publication that a reader today can really enjoy a unique take on space faring habitats and the people who… space fare.

One of my top 20 (or so).

Bob Shaw’s Orbitsville trilogy, but that’s about a star surrounding sphere.

The HALO game’s artificial ring is much smaller than a Niven Ring. http://halo.wikia.com/wiki/Halo_Array

Most SF authors fail at some basic math when it comes to population and how large habitats are, be they natural or artificial. Most of the time they posit far too low of a population number to achieve the Tokyo train rush hour or Kowloon Walled City density they want to have on an whole planet.

Right now the entire human species would comfortably fit within the borders of Texas, with around 1,500 square feet per person.

How can one omit Neal R. Sepehson ‘s Seveneves?

+1 for all the Ringworld references. Niven also did a review of all the LOIS (Large Objects in Space) that were available at the time he was writing Ringworld. Out of a discussion on the Niven-L list, the Bowlworld was developed.

Others to be considered, The space station in “2001 A Space Odyssey”, the space station in “Elysium” , The many space stations and ships in Dr Who,

I think Ben Bova did a story about an Asteroid society.

Finally one of my favourites were the space habitats in “The Expanse”

@55: Over on the Niven list we also invented “DimpleWorld” (a solid dyson sphere with habitats on the outside in concave dimples (picture a golf ball)).

@56 — One of my favorite bits of Niven’s writing is his essay “Bigger Than Worlds” (in his collection Playgrounds of the Mind), which is all about possible megastructures, and in which the Ringworld is somewhere on the low end of the scale.

It the TOR e-mail there’s a caption under the picture that says “HABITATS IN SPAAAACE” If this is a reference to the Muppet Show “PIGS IN SPAAAACE”, I want you to know you’re a genius and I loved it.

@34: I don’t know the local stars enough to verify this for myself, but Cherryh was saying at least as far back as 1981 (when Downbelow Station was written) that our solar system is unusually far from any neighbors compared to those neighbors’ distances to other neighbors; IIRC she developed the Alliance part of her SF universe from observing this gap and expecting that the closer neighbors would be more closely associated. (The physics of her star drive probably wouldn’t stand any scrutiny, but IIRC it isn’t good at long distances, or possibly humans don’t come of the longer jumps in good condition; there are a number of mentions of routes involving dropping back into normal space at one or more random interstellar lumps.) I have seen (but not long enough to study in depth — there was this convention I was chairing) the 2.5-dimension model of local space — a frame holding a series of transparent plates, like a box of giant microscope slides, with stars marked on the nearest plate to their true position — that she used to work out both the Alliance side and the Chanur side.

It’s possible you haven’t run into this argument because it wasn’t key to anything more recent than Finity’s End at the latest; the Foreigner books are in their own removed area, and Regenesis is pretty much based on the one planet.

@59 — Interesting! I’d pay good cash money to see that model of local space, especially as annotated by Cherryh.

It’s been long enough since I read Finity’s End that I wouldn’t remember if she had commented about Sol’s relative isolation. (And apparently contributing to that isolation is the fact that back in the sublight days, Beta Station, in the Centauri system, was found mysteriously vacant a la the Marie Celeste; so even now that FTL is in play, nobody wants to transit to that system.)

I think this is somewhat out of date but if you’d like to spend a lot of time working out how close local stars are to each other, the stellar database is your friend.

Wow, that site is turning 20 this year.

My favorite “space habitat” story is Endgame Enigma by James P. Hogan (1988). It features a Cold War setting where Russia has built a space station called the Valentina Tereshkova. The Russians say it’s a peaceful structure full of towns and agricultural areas; the Americans think it’s really a weapons platform. American scientists are captured and transported there, and have to figure out what’s really going on.

SPOILERS

.

.

.

I put “space habitat” in quotes because it turns out the Russians built a fake “space station” in underground Siberia on purpose so their captured spies would tell their own governments that there were no weapons emplacements. The real space station was loaded for bear, of course. Lots of fun in how our heroes figured out what was going on.

@JD, @hoopmanjh, @chip: For even more demographic details on the local stellar neighborhood, check out the stuff put out by the RECONS project; the January 2019 issue of Sky & Telescope has an excellent write up. It is in fact true that the Sun is slightly further from our closest neighbor than average, but not by an amount that would really qualify as significant. Cherryh’s conceit is thus a bit of a just-so contrivance; I am shocked, shocked to find that an author of speculative fiction would resort to such a thing to power a story.

More notable from the perspective of those hoping to write towards the harder end of SF is that M dwarfs constitute about 75% of the population—a larger fraction than expected. As previously discussed, this suggests that the most easily accessible planets might be habitable (by some definition) but probably not very Earth-like…so there’s a very good chance that human colonization of the local neighborhood is likely to involve a fair number of constructed habitats, even on planetary surfaces.

With that settled, authors can move on to start exploring the urgent issues the people will face on such colonies. You know, the fierce debates regarding whether to focus their constrained resources on the production of poitín or beer…

Cherryh made her map decades ago so the issue might be that the older maps undercounted or misplaced stars near the sun….