Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

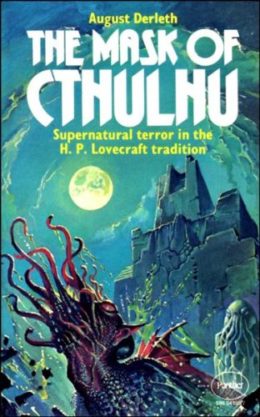

This week, we’re reading August Derleth’s “The Seal of R’lyeh,” first published in 1962 in The Mask of Cthulhu. (Transcription at the link has difficulty with divisions between words, but appears mostly accurate and readable.) Spoilers ahead.

“Here and there, woven into rugs—beginning with that great round rug in the central room—into hangings, or plaques—was a design which seemed to be of a singularly perplexing seal, a round, disc-like pattern bearing on it a crude likeness of the astronomical symbol of Aquarius, the water-carrier—a likeness that might have been drawn remote ages ago, when the shape of Aquarius was not as it is today—surmounting a hauntingly indefinite suggestion of a buried city, against which, in the precise center of the disc, was imposed an indescribable figure that was at once ichthyic and saurian, simultaneously octopoid and semihuman, which, though drawn in miniature, was clearly intended to represent a colossus in someone’s imagination.”

Summary

Marius Phillips has always been drawn to the sea—yet been kept from it by his parents. His grandfather, a man he’s never seen outside a darkened room, warned them to keep their son away from the water. Marius is attending a midwestern college when his uncle Sylvan Phillips dies, leaving him property back east. On the Massachusetts coast. Guess where?

The mansion in Innsmouth is a dreary place; Sylvan preferred the house north of town, perched on a rocky bluff boldly facing the Atlantic. Its principal room is a lofty study crammed with books, hung with outré art from around the world. A handmade rug commands the center of the floor. The strange octopoid design has symbolic significance, Marius decides, for around the house he finds other representations of the being rising like a colossus from a sunken city, surmounted by the astronomical sign for Aquarius. Around the edges appear the unintelligible words, “Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn.”

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Marius moves into the bluff-top house. He ponders a portrait of his uncle as a young man with a strangely flat nose, wide mouth and “basilisk” eyes. From a clerk in Innsmouth he learns the Phillipses partnered with the Marshes in shipping, bringing back—many things. Their reputation means Marius won’t find it easy to hire servants. However, a Marsh might do, and the proprietor directs him to one.

Ada Marsh looks about twenty-five. Though she resembles Sylvan, Marius finds her oddly attractive. But she has an ulterior motive for working at the house—returning early one day, he catches her searching the study. Intrigued, he starts searching himself, and has his first “hallucination” that the house is breathing in unison with the sea below.

He confronts Ada. She says that as he’s a Phillips, he might also be interested in records of his uncle’s wide travels. But he’s not ready, so she’ll say no more.

Nettled, Marius keeps searching. Rummaging behind a shelf of occult books, he discovers a secret recess and, in it, a journal and other papers. From them he makes out that Sylvan was looking for a place called R’lyeh, where Cthulhu waits dreaming. Back in the late 1700s, Capt. Obadiah Marsh and his first mate Cyrus Phillips found the spot. There they acquired wives whose offspring “loosed upon Innsmouth a spawn of Hell.”

The occult books themselves explain much that Sylvan’s notes take for granted. Marius reads about the Ancient Ones—Cthulhu, Hastur, Yog-Sothoth, Cthugha, Azathoth—who were banished from Earth by the Elder Gods. As in all myth patterns, he conjectures, this rivalry represented a “struggle between the forces of good and forces of evil.” In their quest to return, the Ancient Ones had servitor races and cultists. Cthulhu, for example, was worshipped by an amphibious race called the Deep Ones.

Nonsense, but credible press accounts corroborate the myths. For example, there was that government raid on Innsmouth in the twenties…

Learning that Marius has found Sylvan’s notes, Ada challenges him to figure out the meaning of the design in the rug, the Great Seal of R’lyeh. Marius continues his studies. He finds a ring, too, Sylvan’s: massive silver inlaid with a milky stone and the Seal. Wearing it, he feels as if “new dimensions opened up to me—or as if the old horizons were pushed back limitlessly.” His senses sharpen, and he hears again the “susurrus” of house and sea. The ring draws him to a trapdoor under the study rug. It opens on spiral stairs leading far down to a cavern, and into the sea.

Marius ventures into the water wearing scuba gear. He walks along the sea bottom, pulled despite his fear of running out of oxygen. A great fish follows him, indistinct among the seagrass. Just as his air’s gone, it flashes out. Ada Marsh pulls off his diving helmet! He doesn’t drown—instead he begins to breathe water through his mouth, like Ada. She leads him to Devil Reef. Both of them swim with the ease of natural denizens of the deep.

Back on land they “make that compact which bound us each to each,” and agree to go seek R’lyeh. They meet other Deep Ones, search other submarine cities. At last they find a ruined city of monolithic buildings and a stone slab bearing the Seal of R’lyeh. They’ll attempt to break the seal and pass into the presence of Him Who Lies Dreaming. They have heard His call, along with many others, including one who’ll be born in his natural element. Together they’ll rule the sea and earth and beyond, “in power and glory forever.”

Epilogue, a report in the Singapore Times, 11/7/47: Mr. and Mrs. Marius Phillips have disappeared off an uninhabited island, according to the crew of their chartered boat. The manuscript found in Mr. Phillips’ hand is obviously fiction, as any will know who’ve read it above…

What’s Cyclopean: The ruined undersea cities that Ada and Marius explore are megalithic, and monolithic, but for some reason not actually cyclopean.

The Degenerate Dutch: Derleth manages to get through a rehash of “Shadow Over Innsmouth,” complete with shoutouts to a dozen cultures’ mythologies, without a single flail over the horror of those cultures’ existence, and only minor freakouts over interspecies dating.

Mythos Making: The entire laundry list gets checked off, from the Lake of Hali to the Deep Ones to the Abominable Snowmen a.k.a. Mi-Go—all conveniently sorted into Gryffindor and Slytherin. Excuse me, Elder Gods and Ancient Ones. It’s an easy mistake.

Libronomicon: Uncle Sylvan owned the Sussex Fragments, the Pnakotic Manuscripts, Cultes des Goules, the Book of Eibon, Unausprechlichen Kulten… and an unfortunate volume of Dumas, sacrificed to plumb the secret passageway in the study. There wasn’t maybe an ugly statue you could’ve used instead?

Madness Takes Its Toll: Marius and Ada don’t explain their quest to their chartered crew, lest that crew think them mad.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

This is that rarest of beasts: a Derleth story that I actually, mostly, enjoy. Some of that may be my reading format—no e-book available this week, and there’s something about Derleth that benefits from yellowing paper and the warm scent of a half-century-old paperback. We all owe an ancient, unhallowed fealty to Ballantine.

‘Scuse me while I smell this book again.

“Seal” is about two thirds the pleasant tale of a young man coming of age and claiming his inheritance, not to mention falling in love with a young woman whose strength, snark, and ambition match his own. They get married! They have babies! They explore the world! They discover Cthulhu’s bedroom! Though there’s that thing with the geyser, which might indicate the prelude to eucatastrophe, or might indicate that it’s a really bad idea to disturb C’s beauty sleep—maybe there’s a reason why all the Deep Ones swimming around the area weren’t doing so themselves. I sure hope Marius and Ada Phillips are okay.

The other third of the story, alas, consists of a detailed infodump on the Derlethian heresy mixed with random Lovecraft references, broken only by the delightful speculation that Lovecraft’s early death was a result of him Knowing Too Much. (Delightful because it would doubtless have delighted Lovecraft. Friends kill you off in their stories. Real friends kill you off in their stories posthumously.)

I am not delighted by the circular argument that all myth cycles consist of familiar good-versus-evil tropes, that the Mythos offers just such a recognizable archetype, that this makes it believable because it meshes with all those other stories. First, no. Second, no. And third, no, what were you even thinking. Let’s take this fabulous thing that’s nothing like anything else, and make it exactly like everything else? Except not, because this comforting oversimplification isn’t even true of real human cosmologies. Zoroastrianism and Christianity are not actually the universal type, but Derleth could have used a few more classes in comparative religion.

The flip where Marius suddenly starts talking about Cthulhu in Christlike terms is kinda clever. Still not worth it.

One thing that always drives me nuts about these good-versus-evil templates is that you so rarely see a really strong case for good. This is not true for the original dualistic cosmologies: Mithras is the ultra-impressive Unconquered Sun, and Jesus flips tables and preaches radical socialism. But Derleth’s Elder Gods just protect the status quo of physics. I mean, I appreciate the forces that keep my molecules bound together. But breathing underwater, amphibious midnight trysts, and a really sweet book collection? You can’t blame Marius if he barely blinks before diving in.

…though it occurs to me suddenly (possibly because it’s very late at night) that the Derlethian heresy might count as a wildly imperfect first effort to redeem the Mythos, to separate it from Lovecraft’s prejudices. After all, if the vast and implacable forces beyond human comprehension aren’t everyone outside of well-heeled Anglo-Saxon culture… they must be something else, right? Maybe… the devil?

Except that there really are vast and implacable forces beyond human comprehension, and they really are terrifying if you think about them too hard. They just—by definition, if you don’t share Lovecraft’s narrow definition of “human”—aren’t in fact human. The Mythos works best when it builds on such existential truths. And it doesn’t work—or redeem the Mythos’s original sins—to scale it down until it fits in a volume of Joseph Campbell.

Anne’s Commentary

Holy Derlethian Heresy, Night-Gaunt Man! In this story, via Marius Phillips, we get a comprehensive precis of Derleth’s take on the Cthulhu Mythos. Uncle Sylvan’s notes and tomes tell Mythos-naive Marius this truth of the universes:

- In the beginning there were the Ancient Ones. Then, evidently a bit later despite their name, there were the Elder Gods. These two groups didn’t get along. Well, what could one expect when the Ancient Ones represented primal evil, while the Elder Gods represented primal good?

- The Ancient Ones also represented elemental forces. Cthulhu’s element was water, Cthugha’s fire, Ithaqua’s air, Hastur’s interplanetary space (elsewhere, Hastur’s just air), Yog-Sothoth’s the time-space continua, Shub-Niggurath’s fertility, Azathoth—well, It’s just the fountainhead of evil, that’s all, which isn’t an element, but then are interplanetary space, continua and fertility elements? Marius doesn’t mention Nyarlathotep (in fact, he calls Shub the Messenger of the Gods), but the Heresy deems Nyarlathotep an earth elemental, I believe.

- The Ancient Ones rebelled against something, maybe the tedious primal goodness of the Elder Gods. Whatever, the Elder Gods put Their pedal appendages down and exiled the Ancient Ones to “outer spaces.” The Ancient Ones were probably mighty pissed off, but They were also patient in their immortality, for one day They would return to vanquish mankind and challenge the Elder Gods!

- And that’s not all. The Ancient Ones have minions still on Earth, including the Deep Ones, the Dholes, the Abominable Snowmen, the Shantaks, and the Wendigo (Ithaqua’s cousin, on His Mother’s side, I think). The minions sometimes fight among themselves, but in the end they’re united in the quest to return the Ancient Ones to dominion. This is not even counting the human cultists.

- As Marius deduces, the pattern of this mythos is similar to all other myth cycles, including Christianity. The Elder Gods are the Trinity, the Ancient Ones are Satan and his fellow devils. GOOD versus EVIL, remember. The Elder Gods aren’t often named, Marius notices. I notice that, too. Who are these benevolent, people-loving deities, anyway? I guess They’re whoever’s behind the Elder Sign?

Like so many of our protagonists, Marius ends up torn between vehement dismissal of his uncle’s faith and mission and “a wild wish to believe, to know.” He ventures beyond Sylvan’s library, to maddeningly close-mouthed Innsmouth, to Arkham and Miskatonic University. For some reason, Sylvan was one of the few cultist-scholars not to have his own Necronomicon, which forces Marius to consult the MU Library’s copy. But since “Seal” is a short story, Derleth needs to hurry Marius’s belief along and does so by throwing in Sylvan’s senses-enhancing, horizons-enlarging magic ring. The ring not only leads him to Sylvan’s hidden stairway to the sea but into dreams of “all [the alien creatures] given to one cause, the service to those great ones whose minions we were.” He wakes up raring to espouse Sylvan’s death-interrupted quest.

Nor does it hurt that there’s a woman in the equation. Derleth is far less averse to romance than Lovecraft and so gives his Marius an Ada to admire. And Ada is admirable, no shrinking sea anemone, a Marsh worthy of her indomitable forebears. She matches Marius verbal parry for verbal parry, then delivers hits that sting, provoke and steer him toward the truth of his heritage. Then she saves his life, at the same time delivering him into a new one. Plus she rocks the Innsmouth look. Too bad we get so abbreviated an account of her and Marius’s deep-sea search for R’yleh.

Returning to the so-called Derlethian heresy. I haven’t ferreted out who came up with the damning phrase—does anyone know? I wouldn’t be surprised if it were S. T. Joshi, who points out with much vehemence that the universe Howard envisioned is the polar opposite of Derleth’s conception. No benign deities devoted to the salvation of mankind. Probably no deities at all, though we insignificant humans have ample cause to view Lovecraft’s incomprehensibly powerful aliens as gods. Nor, in an amoral cosmos, can those aliens really be malignant, evil. Those are just the labels humans impose on them, given the devastation they could bring down on our heads.

I sit, more or less comfortably, on the picket fence between full-blown Lovecraft bleakness and Derleth hopefulness. Benevolent Elder Gods? No, I don’t put any faith in Them. But I don’t think humanity is insignificant—nor any other species the universe(s) have engendered. Kind of a Yithian attitude, taking the most sanguine view of their archiving drive. As for whether there can be a heresy where Lovecraftian fiction is concerned, I like Chris R. Morgan’s take in his “Cosmic Errors: The Peculiar Legacy of H. P. Lovecraft”: “Derleth’s mythos speaks to a fan-driven impulse to contribute to a creator’s ideas rather than to understand them—not that Lovecraft was wholly averse to such enthusiasm.”

Only I might say that Derleth was understanding Lovecraft’s creation, in his own way. So must we all idiosyncratically understand any idea before we can create from it something—something in our own image, should I say?

Oh, why the hell not.

Next week, Molly Tanzer’s “The Thing on the Cheerleading Squad” offers a slightly different take on the Deep Ones. You can find it in She Walks in Shadows.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

While I suppose it’s not impossible that the Derlethian heresy (a phrase that predates Joshi, to my knowledge) is a retcon to get past some of the less palatable aspects of Lovecraft’s initial vision, it’s more likely an inability on his part to move beyond the Roman Catholic framework of his upbringing. I would argue that the Mythos is in fact easily separable from HPL’s racism and xenophobia. The idea of a vast and uncaring cosmos in which humanity has no meaning was simply too much for someone raised to believe that humanity is the pinnacle of creation and that his ancestry placed him at the pinnacle of that pinnacle. It was an existential horror for him and he found it comforting to lash out at those who seemed culturally more able to accept that (from his point of view, no doubt because they recognized their lack of importance in the human scheme of things). Derleth just couldn’t get past the fundamental concept of good and evil driven into him in parochial school.

I find Derleth odd to read. His Lovecraftian fiction tends to miss the mark. Along with his “heresy”, he makes the common mistake of loading in the names of as many beings and eldritch tomes as he can with no real function in the story. On occasion, he can rise above the level of decently written, but otherwise mediocre fan fiction (this story just barely clears that bar, if at all), but most of it simply doesn’t. The man simply didn’t grok the Mythos. I also find his Solar Pons stories nearly unreadable. And yet, he was a respected author of regional and historical fiction. He was even awarded a Guggenheim fellowship (at the age of 29!), sponsored by Sinclair Lewis and Edgar Lee Masters. I’ve never read any of his Sac Prairie stuff, so I can’t say how good it actually is, but his genre stuff just falls flat.

Bleh. Add this to the list of aquatic-humanoid stories that are probably lovely and that I would probably have enjoyed if I wasn’t a wannabe Deep One and the #keystothekingdom Envy Quill behind my ear wasn’t piercing my brain. I’ll abstain.

Heh. The Iron Druid Chronicles imply that he Wendigo is (are?) possibly the sibling(s) of the Yeti on their Norse-ice-giant mother’s side. Incidentally, those Yeti are awesomesauce even by the standards of that series.

I’m with DemetriosX here- too often, Derleth’s (and Lin Carter’s) mythos fiction reads like a laundry list of Eldritch Elders. A while back, I tracked down ‘The Trail of Cthulhu’ and it was dire. The narrator was too dumb to realize that his boss was drugging him every night (every morning you wake up with your clothes on, yet you keep drinking the ‘space mead’ this sketchy guy gives you?). Even worse, the narrator and the protagonist were hitching rides on byakhee more easily than a Manhattanite can hail a cab.

Oddly enough, Cthulhu roleplaying seems to fit Derleth a lot better than Lovecraft.

@3: Actually it is not odd at all that CoC more seems to align with Derleth. At the time it was being developed, the Derlethian take was how the mythos was generally popularized. Sandy Petersen used Derleth as his template. When I read The Lairs of the Hidden Gods series from Japan in the early 2000s, I was similarly struck by the use of mythos tropes (eg: Cthulhu vs Cthuga, because water vs fire). This is because Derleth was translated into Japanese. I was later told that Stross’ A Colder War caused quite a stir in Lovecraftian circles in Japan when it appeared in translation.

I agree with most point, but Ada reminded me of a RomCom cliche: the woman who’s “different” simply because she’s not blonde and fashionably dressed and also just snarks at the male protagonist. Besides her appearance, I have no idea why Marius likes her; all she does is dangle what he doesn’t know in his face and makes digs at how little his parents taught him. Then she saves him from drowning and suddenly they’re married.

@5. Heh, Manic Ichthy Dream Girl…

I knew about Derleth and Arkham House. Reading-wise, I only remember the Mr. George collection, and some of the Solar Pons stories. (It took Ruthanna’s work and this re-read to make me a Mythos fan) This is my first time hearing of the Derlethian Heresy.

His Sac Prairie work looks interesting- I will have to see what interlibrary loan can do.

@6: There… there are no words. Bravo, bravo!

@6: That was perfect, thank you.

I live to serve!

DemetriosX @@@@@ 1: I don’t actually believe it either, but the later I stay up the more dubious my literary theories get.

Now I kinda want to do a reread segment focused on what Lovecraft’s circle wrote when they weren’t writing Lovecraftiana. Derleth’s award-winning litfic, Bishop’s romance (if only I could find it), de Castro’s melodrama.

Kirth @@@@@ 6: Beat me to it! And improved on it…

I suspect that at least half of Marius’s attraction comes from never before having met a conspecific. And the other half comes from their shared love of R’lyeh and decoding musty journals.

Kirth @@@@@ 6: Beat me to it! And improved on it…

Thanks! Of course, Ophid deserves credit as well. I wouldn’t have thought of the trope without the original comment. Sometimes, ya just gotta have someone else tee the joke up for you.

Ruthanna @11: That could be very interesting. I’m familiar enough with the work of some of them — CAS, REH, Kuttner, Bloch, Leiber, to name a few — but none of those you mentioned. Even of those I know, I don’t really know much outside their weird fiction (stretching the definition to include Conan), except maybe for Kuttner’s SF and all of Leiber’s work. I’ve never read any of Smith’s poetry or Howard’s westerns. Bloch and Leiber both wrote plenty of stuff that is closely allied to Lovecraft’s stuff while still managing to shed the trappings of the mythos. That could also be quite interesting, digging deep to see if there’s any HPL in the DNA of some of those stories.

@11: That’s sort of what irritated me though, they obviously have a ton in common and he’s clearly interested in this side of his family, but she won’t talk to him about it. I can understand her guarded nature since he’s basically an outsider in the beginning (and she probably lost quite a bit of family and community in the 20’s), but setting up a romance on conspecific pheromones alone seemed weak.

Hi

Not a bad choice of a Derleth story. This is perhaps one of the best examples of the Derlethian heresy, he leaves nothing out, Christianity, elementals and as mentioned above an info dump of every contribution to the mythos he can think of. I just reread The Trail of Cthulhu and each tale is stamped out by a cookie cutter as Shrewsbury enlists one poor dupe after another to do the heavy lifting and act as narrator. Pretty dire. I have read Derleth’s Solar Pond as well as his non Lovecraftian weird tales and he is a pretty standard pulp writer. I wonder if part of the reason he pastiches Arthur Conan Doyle and Lovecraft is a lack of imagination or originality in his pulp work. His books Walden West and Village Year: A Sac Prairie Journal were quite enjoyable and much better written, I suspect that was were his heart lay. Still it was nice to see one of the Lovecraft circle include a woman as a real character with a personality and an important place in the narrative. If we had more undersea bits, a greater exploration of Devil’s Reef perhaps I think it could have been even better. Also the reward to Ada and Marius seems well, not great you get to minister to Cthulhu’s wants, sort of like Dante you get to Paradiso and you can sit around in a rose shaped crowd directly contemplating God, and there might be singing I forget. But at least in Dante the results of not earning a spot in the rose have been laid out in great detail. I love the strangeness of Lovecraft cosmicism which I have been finding recently in the works of Brian Hodge, no worry in these stories the critters are aliens and don’t care about us at all. I know you did the Same Deep Waters As You but maybe, could we see It’s All the Same Road in the End or On These Blackened Shores of Time sometime soon?

Happy Reading

Guy

heh. AD is such a boy scout. Such a boy scout.

Speaking as a Slytherin, though, I have a terrible soft spot for reSeers and Deep One apologists.

After all the infodumps and the cut and paste Catholicism faded from memory, I still never could forget the moment when the mask came off.

The truth set him free.

I had probably seen Lovecraftian themes before, but “The Mask of Cthulhu” was my first real encounter with the Mythos.

And oh man, it almost killed it right there. I knew nothing of Lovecraft or Derleth, and since Derleth had a very bad habit of abusing the same tropes in every story in the book- last son, ancient family, old estate, italics, yadda yadda- I quickly grew bored. But there was still something there, a little bit of the alien remained no matter how Derleth tried to cover it up with his standard narrative. This fishy couple was a weird break with the rest of the Derleth stories in the collection, and I wish we spent more time with them.

@3. I disagree about the Call of Cthulhu RPG. I think it aligns most to Lovevraft stories like The Dunwich Horror or The Case of Charles Dexter Ward – an uncaring universe, but one where human action can stave off horror for an interval long enough to be meaningful to humans. Peterson explicltly rejected the “war in heaven” stuff and the elementalism.